First breath … softer

Second breath … deeper

Third breath and fourth breath

Freer and freer

Each breath a new breath

Each breath my own

Each breath a whisper

Of a future still unknown

It would be misleading to suggest that I composed this thoughtful poem right after my escape. Oh, no. In reality, my state of mind was quite the opposite. I was not thoughtful in the least. To put it mildly, I was a cow gone crazy. Giddy and elated, I giggled like a little calf, the way I used to when I was young and Eddie would tickle my nose with a bird feather. Freedom. I was woozy with it. All my worries? Gone. All my sadness? Gone. Imagine the spectacle. Me, in a big forest for the very first time in my life, completely hysterical with joy!

And then, well … my feelings shifted. Just like that, giggles turned into guffaws, heavy and loud. They shook my body. They thundered. They echoed around me, as if to declare “Audrey is here! Audrey stands proud and defiant, afraid of nothing! Afraid of nothing! Afraid of …” (sigh) My emotions changed yet again. Laughter suddenly turned to tears—not full of pain, mind you, or sorrow, but tears of exhaustion, tears of relief. The noose around my neck finally came undone, and I could really breathe again. “Mother,” I said aloud, “I did it. I really did it.”

I came onto the cow caper at five minutes past midnight. For a reporter like yours truly, a story doesn’t get much better than Audrey’s. But I didn’t know it at first because I came late to the party. See, I’m busy chasing leads on the big bank robbery in Metro when I get a call from Tom. Tom? He’s the Daily Planet’s senior editor. “Torchy,” he says, “drop the bank heist and get yourself down to Grover’s Corners double time. We’ve got a hot scoop, and it’s melting fast.” A hot scoop where? “Listen, Tom,” I yelled back. “What kind of lousy hand are you trying to deal me here?” Without missing a beat, Tom says he’s got a cow story he wants me to cover. So now I’m wondering if Tom has gone soft in the head. “What are you, bonkers? Have you flipped your lid? A cow story? That’s the wackiest thing I’ve ever heard!” Don’t get me wrong about Tom; I love the lug, but I wasn’t born yesterday.

My time for celebration was over. I needed to get away from the road if I hoped to make this freedom last. Well, I got my first taste of what the forest had in store for me. I’d never walked through brambles and broken branches before. They cut my legs and scraped my belly. And there were so many trees. Never-ending trees! I’d only ever rested under one tree, the big oak at Bittersweet Farm—a cool oasis on a hot day. But I’d never been under so many trees at the same time. They were extremely tall, with long limbs. I was tiny in comparison. I felt like one of Little Girl Elspeth’s plastic toy animals that could fit in her palm. I was walking among the legs of giants. To those trees, I was nothing more than a speck, barely worthy of notice.

“So what cow story is getting better odds than a bank robbery in broad daylight?” I asked Tom. He tells me that Kent, a junior reporter, was at a place called Connie’s Good Times Grill, which just happens to be down at Grover’s Corners. It’s karaoke night, and Kent starts chatting with a jumpy guy with a few too many root beer floats under his belt. Kasey is his name; he’s an animal mover, see, the Grim Reaper’s delivery boy. He takes cows and pigs to the slaughterhouse to be turned into steaks and cutlets. He’s a cow’s worst nightmare. But it seems the tables got turned. This luckless goofball tells Kent that he lost a prisoner in transit. That’s right; some cow flew the coop, skipped town and ditched her date with destiny. Can you believe it? There’s a cow in a forest, desperate and running for her life, and come morning, there will be a hunting party hot on her trail. Now that’s a story!

Yvonne of Bavaria slipped into the forest never to be seen again. That’s how the tale ends. There are no additional chapters, no sequels; in fact, there are no words written down at all. But how I wished it had been otherwise. How reassuring it would have been to learn what Yvonne did afterward. Perhaps I could have used her actions as a blueprint for my own escape. The Perilous Adventures of Yvonne of Bavaria—both a story and a how- to manual for farm animals on the lam. But there wasn’t. So I continued on blindly, without any particular direction.

The land was hilly, although not high or impossible to climb. I was attracted to any rise because I could see sky peeking between the tree trunks. I craved open space. But it was always an illusion. The hills were no less covered in trees than the lower parts of the forest. What I did begin to notice, though, which proved a beneficial discovery as far as my poor legs and hooves were concerned, were thin lines of beaten-down undergrowth that suggested pathways. They must have served a thinner animal than myself, but I was grateful for even that slight comfort.

We heard her longtime before we seen her. But we knowed that whoever it was, it weren’t no forest creature. The way she stomped through them trees, snappin’ twigs and all, she might jes as well holler her location to every ki-yoot or cougar in the neighborhood. I was stumped. We deer had done created a fine network of useful trails. Why on earth would you avoid them to bushwhack instead? Went on for hours. Spooked the young’uns, ’specially Doris.

Eventually, the sun began to set, and the darker the forest grew, the clearer I could see that I didn’t belong there. How could I have ever imagined that I would fit within those surroundings? How would I survive? I was unsure of what to eat. I noticed half-chewed leaves along the trails from time to time, but the plants were unfamiliar to me; I didn’t know how they might affect my digestion or, worse, whether they would poison me. Then the sky grew overcast, and the wind picked up. Tree trunks scraped against each other, creaking slow and ominous. Pinecones dropped with the gusts. The ones that fell close startled me, prodding my imagination and quickening my heart. I was terribly afraid. My stomachs were twisted in knots. It was difficult to breathe. And then the rain began. Cold, fat drops. I stood there ankle deep in the underbrush, wet and shivering in the wind, too afraid to lie down, and wanting so badly to be back at Bittersweet Farm, warm in the cowshed with Eddie and Madge and … oh, how I missed Mother that night. How I needed her to be close, to reassure me that everything would be okay.

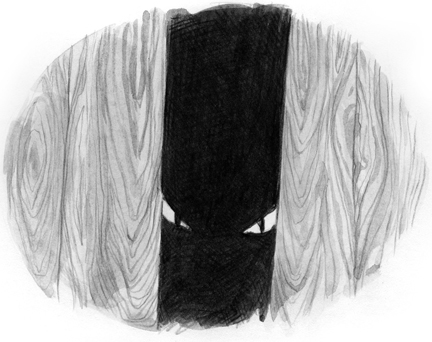

The forest can be cruel. It’s filled with hateful types and uppity sorts. There are the ones who turn their backs on you, and there are the ones who shut their eyes to avoid what’s unpleasant. They’re all the same in my book. And let us not forget evil. Oh, yes, the forest holds that too.… (sigh) She looked so pitiful. Miserable and pitiful. I am not one to get misty about such things, but to see that young lady all alone … my, my, my, sobbing and frightened, exposed to the elements, her head jolting about at the slightest sound, and her as plain to see as a bear cub in a snowstorm. Pitiful. Tugged at my heartstrings, she did. Played sad, sad music somewhere inside old Boris.… Thought I’d forgotten the melody long ago.

Not in my nature to kill anything I haven’t tasted before. But it is in my nature to be curious. Never seen a creature like her. Looked pretty stupid just standing there in the open. Could smell her fear all the way from where I was bedding that night, even in the downpour. I stalked her some but didn’t attack. Stupid doesn’t mean she won’t still put up a fight. Needed to check her out some more. Thought maybe she was a moose at first. Heard stories of cougars taking down moose. Moose are big animals. More meat than on a deer. That girl was no moose though. She might have been big enough, but she had no antlers. And moose aren’t so stupid.

I had bad dreams that night. Oh yeah! I kept seeing the shadow of some scary, gigantic monster-blob-a-ma-jig stomping through the woods, making those exact same crashing sounds we kept hearing the previous afternoon and evening. I could only imagine what kind of face a thing like that would have, you know, with a thousand sharp teeth and claws longer than a crow’s beak. And it would be slobbering, with its tongue hanging low. Right? So I’d wake up all jumpy, and Mama would tell me to hush because she’s fed up with my way-over-the-top imagination, as she puts it, and so then I’d go back to sleep and have the same tootin’ nightmare! Oh yeah! It was an endless cycle of trauma that I can only hope will not scar me for life. But in the morning, we browsed the Red Maple trees and the Witch Hazel, and for a while I heard none of those spooky sounds, which was just fine with me. A fawn wants to eat her breakfast in peace. She doesn’t want no crazy monster-thing sneaking up on her while she’s nibbling on shrubs. Oh yeah!

I didn’t sleep a wink that first night. I was grateful to see the first orange streaks of dawn smudged across the sky. I counted my blessings. I had survived and that was something to acknowledge and be grateful for. Before I left Bittersweet Farm, Roy told me that I should be on my guard. He said that there are creatures other than humans that a cow has to be wary of in a forest. So, as I said, I managed to get through one night, and it gave me a little bit of confidence, even though I was near starving. It was my hunger that gave me the will to keep moving. My muscles were stiff and cold, and the effort was not without pain. But every now and then, I came across thin puddles of water that had not yet drained into the earth. I lapped them up with deep delight. That was my morning: moving from one puddle to the next but keeping an eye out for something familiar to eat.

Jumpin’ June bugs! My troubles were far from over after the flat tire. The cow disappeared into the woods and was gone in a flash. Once I got Red Bessie up and running, I had to tell the folks at Daisy Dream Abattoir that I had lost the cow. I tried explaining about the crazy farm animals, the cow opening the latch and the sudden crow attack. Mr. Ophal, the manager, checked my forehead for a fever! Then he refused to pay me or Bittersweet Farm for an undelivered cow.

So I phoned Bittersweet Farm. Glenn was none too thrilled either, don’t you know, insisting the deal was done once I left his property. Words were flying, and I feared that they were going to make me pay for the cow! But when emotions finally simmered down, we all decided that we should notify the authorities, so that if worse came to worst and the cow wasn’t found, the insurance company couldn’t claim we didn’t at least try to find her. Calls were made, plans discussed, and I’m shuttling between Daisy Dream, Bittersweet Farm and the regional police station, filling out reports and getting razzed by every officer on duty.

By the end of that day, I was as miserable and sorry as a man could be. I headed over to Connie’s Good Times Grill, ready to drown my sorrows in root beer floats and country music. I find myself sitting next to this guy who starts asking me about karaoke night. I was in no mood to answer questions. My nerves were frayed! But when he sees I’m down in the dumps, he lends me a sympathetic ear, and the next thing you know, I’m telling him the whole crazy saga. Of course, I’m expecting him to break out laughing at any moment, just like everyone else. But no, he’s real interested. He’s asking me questions. “What are you going to do about the runaway cow now?” he says. I tell him that the police have called in some forest ranger or something, and he’s going to track down that animal first thing in the morning. “And then what?” the guy asks. “And then what?” I repeat. “And then I’m going to get that darn cow over to Daisy Dream Abattoir and be done with the whole mess!”

Well, the guy just sits there thinking quietly for a minute. Then he pulls out his phone and calls his boss. He’s relating my whole story, including the part about the cow hunt, and it’s slowly dawning on me that he’s a reporter. “No, no, no,” I’m screaming at him. “You can’t be reporting this!” He says, “Why not? You didn’t say it was off the record.” So you want to know the reason I moved out of Maple Valley? I’ll tell you why: it’s having every man, woman and child within a fifty-mile radius read in the newspaper that you were the guy who lost a cow because you were too busy hiding under your truck, from a crow.

Is that what happened afterward? Oh, man, that is so totally, totally wicked!

Hmm? Just speak into the microphone? Starting whe—oh, now? Ahem … AHEM! (cough, cough, cough) … I AM AND HAVE BEEN A WILDLIFE ENFORCEMENT OFFICER FOR—What was that? Too loud? I see.… Ahem, let me start again.

I am, and have been, a Wildlife Enforcement Officer for well onto nineteen years … Better? … Very good. To continue … I received word of the cow in question from my supervisor, who phoned me at my home the evening of the escape. In my capacity as a Wildlife Enforcement Officer these past nineteen years, I have, among many other duties, been assigned to hunt problem bears, cougars, coyotes and such. But up until that point, I had never been ordered to track down a domestic bovine runaway. I was not well-versed in the behavior of cattle gone wild. However, I didn’t foresee much difficulty in this assignment. As it was already dark, and I was deeply committed to the football game I was watching on television, I suggested to my supervisor that I retrieve the cow first thing in the morning. I anticipated no more than a half day’s effort at best.

When I arrived at our offices the next day, I was somewhat surprised to find a Miss Torchy Murrow waiting for me. She identified herself as a reporter for the Daily Planet and insisted on accompanying me in the search. I explained that in order to perform my job, there could be no interference from civilians. I would be carrying a rifle, albeit using tranquilizers rather than actual bullets, and would not want any mishap to occur should the cow in question attempt to bolt. Miss Murrow was not dissuaded. I then proceeded to explain that it was against department policy, which to be honest was not true, and that, besides, she was not dressed appropriately.

This frowning palooka in his spanking-clean uniform is telling me I ain’t got the duds for duty. Well, I nearly blew my stack then and there. I said, “Listen, mister, I’ve hiked through city sewers in a skirt and open-toed heels! You think I’m going to shirk from a patch of mud and a few fallen leaves because I’m sporting a dress and an uptown hairdo? Get used to me, Forest Copper, we’re so hitched together on this hunt, we’ll be sending out wedding announcements by the afternoon!”

Well, yes, I did let her accompany me. I, uh … ahem … Miss Murrow, you perhaps have noticed, is a very persuasive individual.

When Buster was studying the map back at Bittersweet Farm and searching for the best place for me to escape, I had no idea that the patch of green on the paper translated into so much forest. My morning was no different than the first day. I pressed on and on, following the web of trails, moving forward but without any sense of getting anywhere. I was hungry and discouraged. For the first and only time, I considered giving up, walking back to the road—if I could ever find it again—and waiting to be picked up. It was foolish thinking, I admit, and it embarrasses me even now. Had I not been wallowing in self-pity, with no regard for the heroic efforts of all my friends at Bittersweet Farm, I’d have noticed earlier the swath of light behind a row of trees in the distance. And this time it wasn’t atop a hill but straight ahead on flat ground.

I approached with caution, not so much in fear of danger, but in an attempt to curb my hope and not be overly disappointed. There was no need. As I neared, I discovered a beautiful meadow dotted with the blues and reds and yellows of wildflowers! I gasped. “Mother, do you see?” I whispered. “It’s paradise. I’ve found Yvonne of Bavaria’s hidden paradise.” I half expected to see Yvonne herself, grazing on a patch of clover. She wasn’t, of course. But when I did step into the open field, which was deliciously thick with grass, and felt the full force of sunlight wash over my body, I soon discovered that there was someone else.

Two-leggers are infrequent visitors to our parts. The number of times I’ve observed them could be counted on the claws of but three of my four legs. In each case, they came into the forest with one purpose only. They were predators like Claudette, stalking their prey and killing it with shiny sticks that make loud bangs. Two-leggers carry out what they catch; they don’t eat it then and there. Strange hunters, they are. I don’t believe they hear very well, or smell or see well either, for that matter. My, my, my, two-leggers are a feeble sort. They rely on tracks. And scat. Maybe they’ve got other tricks, but if they do, I haven’t figured them out yet. But old Boris has a few tricks under his fur too.

As a professional Wildlife Enforcement Officer, I have maintained standards of performance higher than most. I was not willing to compromise the quality of my work in order to accommodate a member of the press. So I excused myself, telling Miss Murrow that I needed to gather supplies for the hunt and promising to return shortly. In actual fact, I left the building through a back door, snuck around to the front and stealthily slipped away in my truck. After a few navigational errors, I arrived at the reported location of the cow’s escape.

Surprisingly—although less so now, in hindsight—I was greeted by Miss Murrow, who had managed to finagle the truck driver’s report from our office clerk and was waiting by the side of the road with two coffees. I refused her gesture at first, concerned that it was a bribe. However, as the coffee was still hot and smelled strongly of … well, excellent coffee, I felt that in an effort to maintain good media relations for the department, I should accept the peace offering. Ahem. Shortly after that, I got to work.

Cow tracks were evident, both outside the border fence and inside as well. They were not hard to spot; therefore, as suspected earlier, I didn’t foresee any difficulty in pursuing the animal. Only her removal from the forest might be tricky, should she prove stubborn upon capture. I had my rifle at the ready to tranquilize her if necessary, which in turn would allow time to radio in for support. What I didn’t anticipate was that after a half hour of following very clear and obvious tracks, they would suddenly and inexplicably stop.

My, my, my, that’s crazy talk. Impossible for big ol’ animal tracks to suddenly stop. However … should a tree branch full of leaves be dragged along a trail several times over, it’s possible for those tracks to be erased. Heh, heh, heh.

You should have seen the bug-eyed peepers on Humphrey! “What’s buzzin’, cousin?” I asked, ’cause suddenly we’re at a standstill, dead in the water, going nowhere fast. But Officer Stoneface wasn’t saying a word. He’s searching the ground like he lost a contact lens. “Tracks have stopped,” he finally mumbles. “Tracks have stopped!” I yell. “What do ya mean, the tracks have stopped? She’s a cow! What’d she do, hoof it up a tree?” Oh, this was rich. Audrey had learned to levitate. Or maybe she was abducted by aliens. Or maybe the hunted had just outsmarted the hunter. Humph thought he had it easy on this assignment, but hold your horses, the cow just pulled a Houdini! The ol’ Disappearing Bovine Trick! I couldn’t wait to file my report. Headline: Small Town Cow Outwits Authorities. The Hunt Continues!

Hmm? Yes, I did have the misfortune to read Miss Murrow’s account of the first day’s pursuit. Her writing style is somewhat colorful for my taste. And I take offence to the expression “Grumpy Humphrey the Mild-life Enforcement Officer.” For the record, I am able to smile and have, on more than one occasion, laughed mirthfully.

It was like a vision! When she stepped out of the woods into the meadow, she was radiant. Oh yeah! I mean that. Her hide was shimmering golden and creamy. It was something amazing to behold, like when I dream of being grabbed by a giant hawk that swoops down and then carries me high where I can see forever—see Mama and the family below—and everything is peaceful and serene, and the hawk doesn’t eat me in the end? Yeah, amazing to behold like that.

And big? That girl was crazy big! She was so big and beautiful, and her eyes were soft black like night sky and her scent was strange and glamorous, so I knew she was no monster. Mama would call me a fool for being so trusting. But I wasn’t scared. I just had to meet her. Oh yeah! So I did. I walked across the meadow right up to her. “What are you?” I asked. She says, “I’m Audrey. I’m a Charolais, and I come all the way from France by way of Bittersweet Farm. And what are you?” I was speechless, was what I was. She talked in such deep tones, I could feel it rumbling in my chest. “I’m Doris,” I finally managed. “Mama says I’m a handful, and I come from the woods by way of that trail over there.”

Kept an eye on her all morning. Fear smell had gone by then. But still—lapping up puddle water? Too stupid to take the clear stuff from the river or pond nearby. Then she spots the meadow. Whole new scent comes off her. Childlike. Pleasant, even. It was joy. I was sniffing joy. Joy in the forest and too stupid to sense me on her trail. See her grazing like a deer. See her talking with a deer! She’s prey. I knew she was prey. Slow and stupid with plenty of meat. I can take this thing, I thought. It will not be hard. Would have taken her too, then and there, if I hadn’t been distracted.

No one bothers old Boris much. Suits me fine. I prefer a wide berth. If all the forest folk are so afraid of getting “contaminated” in my presence, why should I give a rabbit pellet’s worth of concern for their company? My, my, my, the world is a cold place. Not that any one of them would do more than shun me. I’m not big or particularly dangerous, but they know what I am capable of if cornered. I act the part too, mind you; play up the crazy so they aren’t willing to chance it.

Even Claudette gives me a respectful distance. She and I nearly rubbed shoulders on our visitor’s second day. I’d just finished wiping the trails clean. I was studying this peculiar young lady who calls herself Audrey, this creature that stirs old-time feelings inside me. I was studying her from a few paces back, hiding at the edge of Homestead Meadow. Seemed Claudette was doing some surveillance too. She caught wind of me. Gave me the sneer that serves as her smile. Didn’t come any closer, though. She said, “Boris, your eyes are a whole lot bigger than your stomach if you’re thinking of making that thing dinner.”

I looked right back at her. “That thing has a name, Claudette. She’s a Charolais. Guess you hadn’t figured it out yet, for all your fancy stalking.” That set her back on her heels. Claudette likes to think herself the great hunter, but she’s no risk taker. “Thinking of having a go at her?” I asked. “You don’t want to mess with Charolais. They are vicious as wolverines and stronger than any animal in this here forest. I don’t know why she’s among us, but I sure wouldn’t want to tangle with her.” Now, at the time, I had not the slightest clue what a Charolais was or was not capable of doing. The young lady looked kind and gentle. I just wanted to buy her a little time before Claudette’s stomach grew bigger than her eyes.

Doris was my first forest acquaintance. She looked as delicate as a dandelion seedpod with her small brown and white-dappled body perched on thin, wispy legs. I thought she might float away on the slightest breeze. Once she got over her shyness, there was something familiar in the way Doris bounced about while she talked a mile a minute, so fast I couldn’t keep up half the time. She reminded me of Eddie when he was a pup. And I suppose she reminded me of myself too, telling me of her dreams and nightmares as vividly as if she were still in them. Doris could have been a younger sister, and it gave me pleasure to think of her so. I grazed contentedly while she babbled on, enjoying the sensation of eating the grass as much as tasting it. Each tug and chew of blade was acknowledged. Each swallow, a solemn moment of gratitude as my long stretch of hunger came to an end.

Needs jes a second out of my sight to get herself all mixed up in no-good, my Doris. Once stuck herself on a rock cliff, tryin’ to explore a nest. Sneaked her foolish self onto a porcupine too, pretendin’ she be a ghost, and got herself a snoot full of quills for her efforts. Now this. Had I seen what she was doin’ back there in Homestead Meadow, I’d have put a stop to it before it began. I would have avoided the meetin’ ever takin’ place. But like I said, with Doris, all it takes is but a second.

Doris led me across the meadow until it dipped, and I saw not one but a whole group of deer grazing. In unison, the heads raised, but I easily guessed which of them belonged to Doris’s mother by the stern look on her face. We neared at a pace set somewhere between Doris’s excitement and my hesitation. I tried to disarm her mother with a polite introduction, as Mother would have encouraged me to do. I managed no more than “How do you do? My name is—” before she cut me off.

I said to her, “I know what you are, girl. I’ve done heard accounts of your kind from family lore. Different color, mind you, but you still fit the bill. Your type lives within the fences, with them two-leggers. You don’t belong here, do you?” I said, “Do you?”

I did not know why Mama was being so mean and cold, treating Audrey like she was dangerous or something. I tried to explain to Mama that Audrey was alright and we didn’t need to worry about her even if she was different from us. In fact, Audrey wasn’t all that different, because her and me, we discovered we ate the same way and that our stomachs were almost the same too. Oh yeah! I tried to tell Mama that, but she just hushed me up.

“No, ma’am,” she answered. “This isn’t where I belong. It’s just that I have nowhere else to go.” Um-hmm, jes as I was supposin’. But then, this here Audrey, she done explained her situation. I swallowed a heavy lump, hearin’ her tale. That poor girl had barely outgrown her childhood and yet she was carryin’ woes heavier than a turtle with two shells. I had nothin’ personal against Audrey. I could see right from the get-go that she was no direct threat, which is why I let Doris indulge in her foolery. But only up to a point. Audrey might have been fine in manner and scent, but that don’t mean she weren’t dangerous. A big, passive creature like her has got herself a target on her hide. I didn’t want Doris close by when the howls and growls made their move. I said, “You are welcome to graze and browse with us durin’ the day. Come nightfall, we part company. You may not bed with us. If you survive until dawn, you may join us once more. And if durin’ the day there is trouble, we won’t wait for you. Is that understood?”

I said, “Yes, ma’am.” To be honest, I was very surprised to hear her talk as if danger was lurking just around the corner, because other than my active imagination and Roy’s warnings, I had not encountered anything that I found life-threatening. But I wasn’t one to argue with my elders, and I was grateful to have any company in my new forest life. As for where to bed at night, that problem was literally solved right then and there. Doris’s family continued grazing, and as their progress took them over a small rise, suddenly I saw buildings at the far end of the meadow. I gasped in astonishment because before me was Bittersweet Farm.

Only it wasn’t Bittersweet Farm, you see, it was another farm, complete with a small house and barn and fences, but all in terrible disrepair. It must have been abandoned many, many years earlier. Grass and weeds grew right up to the doorstep. The house might have been a cozy and cheery place in its prime, a place for a child like Little Girl Elspeth to feel content in, staring out the window toward the meadow on a cold, frosty morning. But now the remaining bits of red paint were faded, the chimney had crumbled and the roof had caved in toward the middle. It was as if the house had given up trying to pretend it was still a home and had sighed so intensely it broke itself and finally collapsed.

As for the barn, it was no more welcoming. It too was much smaller than what I had known, with a low sloping roof. Trees had grown right against the wood-slatted walls, and moss and ivy covered the shingles like hair, hanging over the edges in unkempt tresses. The barn door was pushed inward, held askew on a single, bent hinge. I squeezed myself through, feeling as if I was forcing myself into the dank, dark mouth of some long-sleeping creature. I half expected to be chewed and swallowed at any moment.

Inside the barn, I was pricked by a dozen narrow shafts of afternoon sun that poured through the many holes in the roof. I was intrigued by the strange patterns they created. But holes also meant that the roof offered little in the way of protection from the rain. I took a moment to consider whether this broken-down dwelling could be my new home. It was not ideal, that was certain. It was neither comfortable nor comforting. But I only needed some protection in the night, so I decided it would suffice.

It was all good! Mama let Audrey be family with us, and I got to show her all the different plants she’d never seen or tasted before. And that girl can eat. Oh yeah! I showed her the pond and the river where the water is cool and tasty. I showed her the best trails and the warmest spots to rest. And Audrey told me about Bittersweet Farm, Eddie and Buster, the lake called Atlantic, and the place called France where we decided we would go together and taste the clover and meet all her cousins.

When twilight came, which is when my jitters always get the best of me on account of the silent snatchers that roam the midnight woods, Audrey would nuzzle and lick my ears with her crazy big tongue. She’d tell me happy stories that I could take into my dreams so I could sleep better. Then she’d say good night and head over to Homestead Meadow to bed in her barn. Before I closed my eyes, I always wished really hard that Audrey would be okay and survive the night, so that I could see her at dawn the next day.

I continued to hunt for the cow for several days. I also continued to be accompanied by Miss Murrow, or Torchy, as she insisted I call her. Each morning I would encounter fresh bovine tracks that confirmed the animal was still alive. But consistent with the first day, her trail would simply end for no reason. Remarkably too, whereas I had expected to find what civilians often refer to as “cow patties,” I discovered none whatsoever. Nor was I able to smell evidence of any, due to an almost unfailing cloud of skunk odor that hovered above the trails.

Contrary to what … uh, Torchy wrote in her daily news reports, I was not frustrated or befuddled, nor did I ever throw down my Wildlife Enforcement Officer cap “in a fit of utter exasperation.” That would have been highly unprofessional. I was not put off by these setbacks, as I am a patient man. I was most willing to continue in the pursuit of the cow on my own. However, due to the growing public interest in the story generated by Miss … by Torchy, my supervisor felt that a larger team of officers could end the hunt more quickly.

Poor Humphrey-Dumphrey. Come day four, his boss is chewing his ear off, demanding results double time, or threatening to demote Ol’ Humph to a guard at a petting zoo. I felt for the lug, I did. But as a reporter, I’m rooting for the gal fighting for her life. Did I milk the story? You better believe it, sister! I knew I had to slant this tale in the cow’s favor, see. The readers needed to put themselves in Audrey’s—that was her name, you know—Audrey’s shoes. Not that I’m saying she was wearing a pair of loafers, but I wouldn’t put it past her. That gal had pizzazz and plenty of moxie. We’ve all been there, see; we’ve all been backed into a corner with no place to go.

But stop the presses! Audrey was a story that wouldn’t go away. Four days running, not a sign of her. I’m thinking if the cow keeps it up, I’ll have a two-week series, and maybe it will even go national! Round five takes a twist, though. Now I’m following a half dozen officers into the woods, each one of them more stone-faced than the next. Heck, Ol’ Humph was starting to look like Chuckles the Clown by comparison!

Nights in the barn were never pleasant. I had no hay to soften the ground, and the air was stale; I felt like I was stuffed away in a musty old box. It was the opposite of freedom. The sky stayed clear and the moon was waxing. Its light seeped in, sometimes cross-hatched across my flank, like fence chain, hemming me in even more. Those were the loneliest times.

Back at Bittersweet Farm, I’d have drifted off to sleep with the hushed voices of Madge, Greta and the other ladies in my ears. Now, there was nothing soothing, nothing familiar. So I would make myself remember as vividly as possible all of the friends I had left behind. I’d think of Eddie and Buster and Roy. I was squeezing drops of comfort out of my memories the way Farmer squeezed water from a wet rag. There was Eddie running and barking with joy. There was Buster, his little eyes twinkling at a newly filled trough. Squeezing and remembering, squeezing and remembering until I could wring out a small smile. But memories are double-edged. They may warm you with happy thoughts of what you once had, but knowing you no longer have them leaves you cold, shivering and alone.

The fifth night was different. The fifth night was the worst. I heard sounds from outside, close to the wall. Padded steps with the faintest rustle of grass, controlled breath, a smack of lips, and then I saw a shadow projected onto the dirt floor. It was of a tail, rope-thick and long. I stared, near hypnotized as it slowly coiled and uncurled, while behind me, a voice growled low and soft as a lamb’s ear. “Been watching you, Charolais,” it said. “Wondering if you’re dinner.”

I jumped to my feet and turned, catching sight of two fierce amber eyes peering in between the slats of wood. In a split second they were gone, as if I had imagined them. But I didn’t. I could feel menace encircling the barn. I tried to keep track of the stranger’s whereabouts, constantly shifting my position as she resumed prowling, first one way and then the other. “Hear you’re dangerous, Charolais. Are you dangerous? Smelling fear now and, mmmm, that makes me so hungry. Wondering about you, Charolais. Wondering … but close to deciding.”

She was out of the moonlight’s reach, which meant she was nearer to the door, which foolishly I had always left open. “Why should I be afraid of you?” I asked, attempting a light, breezy quality to my quivering voice. “We’ve never met, and I could not imagine you would mean me harm.” While I spoke, I walked as quietly as I could manage toward the door. I listened for any twig snaps or breath exhales. Then silence fell upon the barn as deafening as a roar. Intentions were clear; the time for waiting was over. I saw a fan of whiskers caught in the moonlight, barely extended into the doorway. With all my force I pushed against the door, casting out that yellow-eyed beast while catching a few of her whiskers in the doorjamb. She screamed and growled madly; strong, hard nails scratched and clawed at the wood. The pressure against the rickety door was formidable. She pounded once, twice, again and again. Oh, my, the threat was horribly clear: if I was to ever meet this creature in the open, exposed and unprotected, I would be no match for her at all. I would be her dinner.