The Federal Gas Tax Cession: From Advocacy Efforts to Thirteen Signed Agreements

INTRODUCTION

The gas tax cession program constitutes the most significant federal fiscal intervention into urban affairs in more than a quarter of a century. Owing to financial constraints, concerns about provincial jurisdiction over municipal affairs, and the unsatisfactory experience with the Ministry of State for Urban Affairs in the 1970s, Liberal and Conservative federal governments for most of the 1980s and 1990s were reluctant to intervene in urban affairs (Andrew 2001). But a continuing deterioration of the physical and social infrastructure of cities motivated the creation of a very strong and vocal urban policy community that was able to slowly raise urban issues on the federal agenda, ultimately resulting in the emergence of the federal gas tax cession program for municipal infrastructure.

In this paper, we trace the development of this agenda and the federal approach to the program, and we discuss its major characteristics, highlighting its innovative features and their possible impacts.

THE EMERGENCE OF AN URBAN AGENDA

With the elimination of federal deficits and the emergence of large surpluses in the late 1990s considerable pressures were mounting for Ottawa to use its fiscal resources to the address the concerns of municipal governments. These pressures came from several quarters. Interest groups, academics, think-tanks, media outlets, and municipal and city employees, among others, developed different channels of advocacy that constantly reminded the federal government that Canada is now one of the most urbanized countries in the world,1 that many cities are singularly ill-equipped to cope with the responsibilities downloaded to them,2 and that there are a whole range of federal policy concerns, including economic innovation, competitiveness, and the quality of the environment, that inevitably have an urban dimension (Anderson 2002, 4–6). Additional arguments pointed to the impact of federal (and provincial) policies on municipalities and municipal budgets. A prime example was immigration, which imposed costs on municipalities for settlement programs, education, and public health.

Discussions of Canadian economic growth and productivity increases in a global era focused increasingly on the importance of cities as the foci of economic activity.3 Well-functioning cities were seen as the key to economic success, and that in turn required renewed physical infrastructure, human capital investment, and culturally rich environments. Large investments were required to make leading Canadian cities competitive. Infrastructure investments such as transit, roads, water, and sewage cases were particularly promoted, perhaps because the municipal advocates knew that politicians like to be seen taking action to address very visible problems, but more fundamentally because the deterioration in the existing stocks was becoming a major concern.4 The cities argued that the higher orders of government, particularly the federal government, should assume responsibility for these costs and increase the financial resources available to the cities. These arguments were even more sharply stated in the case of Ontario, where the downloading of the Harris Conservative government in the late 1990s increased the fiscal straits of the municipalities.

By the early 2000s, the federal government seemed ready both financially and in principle to embrace a new urban strategy. Pressured by a group within the caucus that had been pushing for a city agenda, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, while still hesitant to move forward on this file, created a Caucus Task Force on Urban Issues (chaired by MP Judy Sgro) in 2001 to identify ways in which the government could better focus its efforts in cities to sustain and enhance their quality of life (Randa 2001). By 2002, Finance Minister Paul Martin was recognizing publicly that cities were entitled to a new deal to address their shortcomings and to be prepared for the economic challenges and transformations brought on by globalization (CBC News 2002). At the same time, the task force released its final report, “Canada’s Urban Strategy: A Blueprint for Action,” which supported the view that federal assistance was needed in municipal infrastructure renewal and which provided, through its recommendations, “the building blocks of a national urban revitalization and innovation agenda” (Sgro 2002).5 Despite these developments, the move from policy prospects to implementation was delayed, first, by the uncertainty brought by the Liberal leadership race that culminated at the end of 2003, when Paul Martin succeeded Jean Chrétien as prime minister, and then by the 2004 elections that yielded a minority government in which the Liberals remained in power.

As prime minister, Paul Martin was committed to moving forward, and after the election of 2004 the cities and communities agenda was placed front and centre. First, Martin asked former British Columbia premier Mike Harcourt to head the External Advisory Committee on Cities and Communities (EACCC) to, among other things, “develop a long-term vision on the role that cities and communities should play in sustaining Canada’s quality of life, enrich the discussion of policy options, and provide advice on how to best engage provincial, territorial and Aboriginal governments” (Infrastructure Canada 2006).6 Then the government used the February Speech from the Throne to officially introduce what Martin had been promising on the campaign trail: a New Deal for Communities. The Speech highlighted that this deal would target the infrastructure needed to support quality of life and sustainable growth; would help communities become more dynamic, more culturally rich, more cohesive, and partners in strengthening Canada’s social foundations; and would deliver reliable, predictable, and long-term funding (Clarkson 2004). Moreover, the Speech from the Throne acknowledged the government’s intent to set up the agreements to transfer funds to municipalities that were at least nominally linked to the federal gas tax.

For many years, key players – including big city mayors, like Winnipeg’s Glen Murray and Vancouver’s Larry Campbell, municipal associations, such as the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM), and academics – had been calling for the share of a portion of the federal revenues from fuel taxes to be devoted to addressing municipal fiscal needs. For example, advocating for new urban financing tools, the FCM argued in 2001, on both their Federal Budget Submission and their Brief to the Prime Minister’s Caucus Task Force on Urban Issues, that the federal government had an opportunity to apply nationally programs already in place provincially (FCM 2001b). They were referring to the actions of Alberta and British Columbia (and later Quebec) that had committed a certain portion of the provincial revenue from fuel taxes collected within the boundaries of large cities to support long-term transportation planning and development. While Paul Martin had openly rejected these proposals in 2001 because he believed that dedicated tax schemes lead to distortions of taxation and spending (Mohammed 2002), the key players kept pressuring the government on the issue, and they gained a partial victory when the gas tax transfer was finally announced.7 The victory was only partial because, among other things, once the details were revealed it became evident that (1) the government was not sharing all its fuel taxes, only excise taxes on gasoline; (2) it was originally a five-year program, not a permanent measure; and (3) it was not limited to the big cities or to transportation projects.

After the Speech from the Throne, stakeholders were hoping that the sharing of the gas tax would be scheduled in the 2004–05 fiscal year, but owing to financial and administrative challenges the government was unable to do so. According to John Godfrey, who was first appointed parliamentary secretary with responsibility for urban affairs and then named minister of state (infrastructure and communities), it was important to “find some new incremental source of money – not just re-announced old money – and do it in a way that was clean administratively,” and that would not “come back and embarrass us because we did not figure out how to do it right” (CBC News 2004).

The government was determined to avoid federal-provincial fights that are always in danger of erupting whenever it ventures into an area that impinges on provincial jurisdiction. For this reason the Martin Liberals did not want to become involved with vetting individual projects, nor were they attracted to traditional forms of conditional grants, the history of which is not uniformly happy and squabble-free.

At the same time, in the environment of the “sponsorship scandal” the new religion in Ottawa was accountability. The government sought a regime that would assure them that the money they were prepared to transfer to municipalities for infrastructure would indeed be used for that purpose. Out of these somewhat conflicting concerns, they devised a plan that drew heavily on the contribution agreement model long used to provide funding to a wide variety of non-governmental agencies. A conventional contribution agreement involves the federal government granting a sum to an external agency that has agreed to carry out a specific set of activities. As in a contribution agreement, funds would be transferred to municipalities based on municipal plans to invest in approved categories of infrastructure. Reports would be filed at the back end of the process indicating how the funds were expended and what outcomes were achieved. Unlike the practice in a conventional contribution agreement, there would be no specification of defined categories of eligible expenses.

The creation of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Communities8 and the 2004 budget, which announced a series of municipal initiatives – the full rebate of GST paid by municipalities, accelerated federal spending through the Municipal Rural Infrastructure Fund, extensive funds for the cleanup of federal contaminated sites, and greater coordination of programs for urban Aboriginal people (Department of Finance Canada 2004) – were promising moves from rhetoric to action. As parliamentary secretary, Minister Godfrey went across the country for six months to consult with mayors and councillors and the relevant provincial ministers about what such a new deal might look like. After this journey he revealed, in front of the second Canadian National Summit on Municipal Governance, the first details of the gas tax transfer.9 While the exact amount was not determined, he mentioned that the total sum over a five-year period would be between $4 billion and $5 billion and explained the challenges of designing the transfer to ensure (1) that it was sufficiently simple so that municipalities could understand the rules, (2) that provinces did not claw back their current level of support, (3) that the money went to the municipalities and that it was spent in some measurable incremental fashion on sustainable infrastructure, and (4) that it met the needs of the smaller communities, as well as the largest cities, in ways that were relevant (Godfrey 2004b).

After long consultations with key players, such as the FCM, city mayors, and councillors, and after internal discussions between the Ministry of Infrastructure and Communities, Cabinet, and the Treasury Board, the government was ready to finalize the details of the New Deal. They were revealed in several communications in 2005 and subsequently made official in the 2005 budget. In relation to the Gas Tax Fund, this budget outlined (Department of Finance Canada 2005) that

• Starting in 2005–06, the federal government would share with municipalities 1.5 cents per litre, or $600 million in revenues. By 2009–10, this amount would increase to 5 cents per litre, or $2 billion annually.

• The federal government wanted all projects receiving the money to help fund local environmentally sustainable infrastructure.

• The gas-tax money would be given to a province or territory, which in turn would hand the funding over to municipalities, according to deals being negotiated in each jurisdiction.

• The federal government would allocate the funding on a per capita basis to provinces, territories, and First Nations.

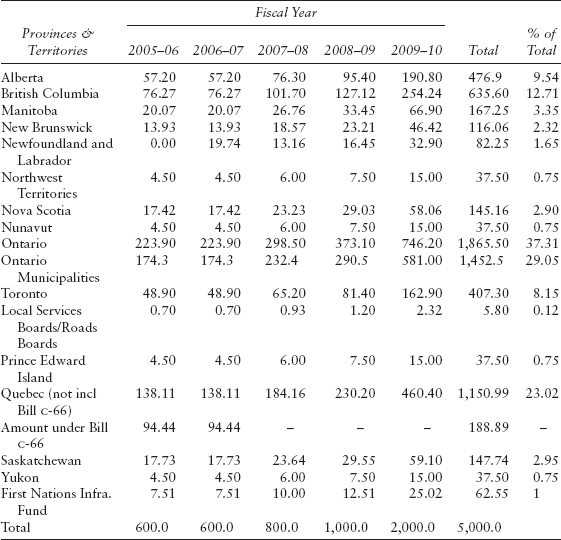

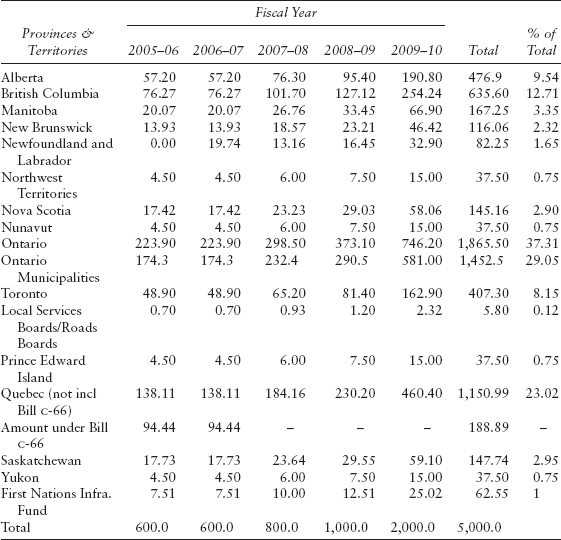

As Budget 2005 specified, the bulk of the funds were scheduled for the concluding years, ending at $2 billion in the fifth year (see table 5.2). The reasons for this were two-fold: first, the government, and in particular the Department of Finance, wanted to push the major commitments further into the future; and second, it was believed that back-end loading would give the municipalities time to formulate better investment plans.

At the same time, the Gas Tax Fund was notionally linked to the federal revenues from the excise tax on gasoline. This is intuitively appropriate, since the tax is collected from drivers and vehicles that impose considerable costs on municipalities for road construction, maintenance, snow clearing, and policing. Thus, linking this revenue to infrastructure investment seems logical. But in fact, there is no specific link. The federal excise tax on gasoline generates about $4 billion per year. The amount of the federal transfer does not depend on collection levels and does not vary if collection levels increase or decrease. Rather, the program is financed through a charge against the government’s Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF), initially amounting to $5 billion over five years.

With this program there was no longer any doubt that Ottawa was finally engaged in municipal concerns. Within the federal government there was a view, though not universally held and certainly not overly touted, that the gas tax transfer could open the door to a new relationship with municipalities. Our research has revealed that this was based on several factors: (1) the FCM played a leading role in advancing the case of the municipal sector and contributed to the formulation of the general design of the program; (2) Prime Minister Martin and John Godfrey consulted directly with mayors in the early stages of formulation of the initiative; (3) in some cases municipal representatives participated directly in the negotiations (representatives from the City of Toronto, of course, being the most notable); and (4) in two provinces (details below) the administering agency for the funds was not the provincial government but an association of municipalities. An observer so inclined could interpret all these factors as portents of a new era of federal-municipal engagement.

In May 2005, Alberta signed the first agreement, and after just seven months twelve of the thirteen agreements had been signed by the other provinces and territories (Newfoundland and Labrador signed in August 2006). In 2007, the Harper Conservatives rebranded the Gas Tax Fund under the Building Canada initiative and extended the funding from 2010 to 2014 at $2 billion per year. Then, in response to ongoing requests for stable, long-term funding, the 2008 Budget announced that the Gas Tax Fund would be extended at $2 billion per year beyond 2014, becoming a permanent measure.

PROGRAM GOALS: NEW GOVERNANCE DYNAMICS AND SUSTAINABILITY

In principle, the design of the gas tax transfer reflected the four key elements of the New Deal and complied with the four-pillar model of sustainability on which the New Deal was based. The fact that Infrastructure Canada had been part of the Environment Canada portfolio (December 2003–June 2004), and the existence of national and international environmental commitments, such as those defined in the Kyoto Protocol, resulted in an emphasis in the program goals on green projects and sustainability. On the other hand, the emphasis on hard infrastructure was the result of an overwhelming municipal consensus that emerged during the consultations. While there was pressure from key stakeholders to earmark the money for big cities, the gas tax transfer was designed with the belief that no municipality or project was too small. Overall, what characterized the New Deal was an attempt to “consider communities as a whole – one that takes each piece of the puzzle and considers how it fits with others to create the big picture” (Godfrey 2004a). More than money, it called for government players to become more aware of the effects of government programs and policies at the local level.

The first of the four elements of the New Deal was an overarching vision of where Canadian cities and communities of all sizes should be in thirty years. To achieve this vision, the government established the improvement of the quality, efficiency, effectiveness, and sustainability of environmental municipal infrastructure as general goals of the gas tax transfer, as well as cleaner air, cleaner water, and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions as specific outcomes. The second element was money, and the government saw the transfer of the gas tax as a viable, politically appealing option for addressing the need for stable, predictable, long-term funding for municipalities. The third element was utilizing an urban lens when designing policies that would require the involvement of all levels of government with the cities and communities. Municipal leaders were part of the negotiating process leading to the signing of the agreements, and their needs were reflected in the emphasis that the goals placed on the funding of hard infrastructure and the abandonment of the cultural aspect that was, in principle, part of the New Deal. Finally, the fourth element was building new relationships with municipalities – based on responding to local needs – and with the provinces and territories, because they have the jurisdiction. To this end, the gas tax transfer created purposeful partnerships and emphasized flexibility based on the belief that municipalities know what is better for them and will use the money accordingly.

The framework in which the choice of these elements was based rested on a model of sustainability that depends on four interlinked dimensions: environmental responsibility, economic health, social equity, and cultural vitality. Since the early 1990s, sustainable development has become a key goal of public policy within Canada and internationally. According to the Report of the Brundtland Commission, Our Future: “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of the future generations to meet their own needs. Sustainable development is not a fixed state of harmony but rather a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, the orientation of technology development and institutional change are made consistent with future as well as present needs” (World Commission on Environment and Development 1987).

Understanding that there is a connection between quality of life and human health, social equity, long-term planning and integrated decision-making, resource efficiency, technological development, and governance and institutional change, the federal government saw the New Deal as a viable way of moving forward with the sustainability and green agenda (Godfrey 2004a). This commitment is expressed in the preamble to the gas tax agreements, where the government establishes that the program should

• foster vibrant, creative, prosperous, and sustainable cities and communities across Canada, and enable all Canadians to achieve a higher quality of life and standard of living;

• develop environmentally sustainable municipal infrastructure (i.e., things like urban transit, water projects that pay for themselves, new garbage disposal systems, and for some small communities the rehabilitation of roads and bridges, and community energy systems) and enhance existing infrastructure to aid in their economic, social, environmental, and cultural development;

• recognize that all orders of government must work together-collaboratively and in harmony to ensure that investments in communities are strategic, purposeful, and forward-looking; and

• recognize that open communication with the public will best serve the right of Canadians to transparency, public accountability, and full information.

In addition, to “accelerate the shift in local planning and decision-making toward a more long-term, coherent and participatory approach to achieve sustainable communities” under the agreements, the signatories are required to ensure that municipalities or some higher level of agglomeration develop Integrated Community Sustainability Plans (ICSPs) (Planning for Sustainable Canadian Communities Roundtable 2005). These plans, which require members of the community to integrate and share knowledge and solutions, are expected to allow cities, communities, and First Nations to better understand their future and work collectively towards achieving their goals. With an ICSP they will be able to choose project priorities, manage efficiently and effectively their resources, deliver required services, and monitor their progress towards achieving desired outcomes.10

The negotiations leading to the signing of the agreements were completed quickly and the process was remarkably smooth. This result was attributed to several factors. First, because there was a political imperative, the negotiations were done by three federal teams covering the provinces and the territories simultaneously. This limited the opportunity for each province to hold up the process in order to see what the others were doing. Second, Infrastructure Canada had already dealt with a lot of the provincial and municipal players, establishing a good rapport that aided the negotiating teams; there were no real surprises at the negotiating tables. Third, the negotiations were done under the label of “infrastructure” instead of “cities,” which could have been a more contentious issue, especially in Quebec. Finally, a template for the agreements that had been approved by Treasury Board represented a good starting point to the process. While in the past negotiating with Infrastructure Canada had been difficult, because they usually presented municipalities with a deal fully drafted and pre-approved by Treasury Board, with the gas tax it was different because, as one interviewee remarked, “they came with some guidance, but did not have the A&Zs.” Overall, as a result of the federal approach to the issues, the minimal strings attached to the transfer for the provinces, and the strong motivation by the municipalities to access infrastructure investment money, there was a positive and non-adversarial atmosphere at the negotiating tables. Table 5.1 sets out the signing schedule for the various participants in the program.

The agreements that were finalized with the provinces are in the main, remarkably similar and are predicated on provincial/municipal commitments and plans at the front end and on back end accounting. The template approved by Treasury Board was, for the most part, tailored only marginally across the provinces. There are, however, a few key arrangements, particularly in Ontario and British Columbia, and to a lesser extent in Quebec.

Common Elements

GOVERNING PRINCIPLES

In November of 2004 Minister Godfrey was invited to a meeting of the Provincial and Territorial Ministers Responsible for Local Government where possible guiding principles for the Gas Tax Fund were discussed. Initially, all the provinces and territories agreed on a set of broad principles, but the federal government felt that they lacked an emphasis on accountability. After further discussion, they all agreed on a set of six principles common to all of the agreements with the exception of Quebec:

Table 5.1

Signing Schedule for Participants in the Gas Tax Program

Signatory |

Date |

Canada – Alberta |

14 May 2005 |

Canada – Yukon |

26 May 2005 |

Canada – Ontario – Association of Municipalities of Ontario – City of Toronto |

17 June 2005 |

Canada – Nunavut |

3 August 2005 |

Canada – Saskatchewan |

23 August 2005 |

Canada – British Columbia – Union of B.C. Municipalities |

19 September 2005 |

Canada – Nova Scotia |

23 September 2005 |

Canada – Northwest Territories |

10 November 2005 |

Canada – Manitoba |

18 November 2005 |

Canada – Prince Edward Island |

22 November 2005 |

Canada – New Brunswick |

24 November 2005 |

Canada – Quebec |

28 November 2005 |

Canada – Newfoundland and Labrador |

1 August 2006 |

1 Respect for jurisdiction. Canada, the provinces, the territories, the UBCM, the AMO, and the city of Toronto (i.e., the signatories) agree to respect the roles of all orders of government, and to recognize the merit of partnerships to support the New Deal.

2 A flexible approach. In recognition of the diversity of Canadian provinces and territories, First Nations, regions, cities, and communities, all the signatories agree to a funding allocation formula and delivery mechanism to meet the specific needs of their respective local governments.

3 Equity. Canada commits to treating provinces, territories, and First Nations equitably. Furthermore, the signatories commit to ensuring equity between urban and rural/remote communities, recognizing the different capacities of local governments.

4 Focus on long-term solutions. The signatories recognize the need to establish a long-term vision for Canadian cities and communities that requires permanent collaboration between all orders of government on issues that significantly affect cities and communities.

5 Transparency. The signatories agree to use an open and transparent process for the purpose of implementing their agreements and to develop performance measures to enable regular reporting to Canadians on the outcomes achieved with gas tax funds.

6 Accountability and reporting to Canadians. The signatories commit to due diligence in the management of gas tax funding and to using appropriate mechanisms to report regularly to the public on the expenditures and outcomes of the gas tax investment.

ALLOCATION OF FUNDS

The Federation of Canadian Municipalities played a useful role as the gathering point for contradictions and conflicts among municipal views with respect to the allocation of the federal funds. Small municipalities wanted money allocated by population, while larger cities argued that they should get a disproportionate share because they had more pressing infrastructure needs, especially in the area of transportation. The government also had to take into account the existence of unincorporated areas, First Nations territories, and the differences across provinces.

Ultimately the government decided to allocate the money under the agreements to the provinces based on population (see table 5.2), but to ensure that the smallest province, Prince Edward Island, and the territories (Northwest Territories, Yukon, and Nunavut) received an adequate level of funding, the government decided to set a base amount of $37.5 million that was equally allocated to each of them. Similarly, in recognition of the unique circumstances that characterize First Nation communities their allocation was set at $62.55 million.

The contributions were to be paid in equal semi-annual payments (the first not later than 1 July, and the second not later than 1 November) in each fiscal year. The payments for 2005–06 and 2006–07 were equal, representing 12 percent of the total allocated amount, and then they increased progressively each year: 16 percent in 2007–08, 20 percent in 2008–09, and 40 percent in 2009–10. The exception was Newfoundland, which got 0 percent in 2005–06 and 24 percent in 2006–07, because it signed the agreement in August 2006, and First Nations,11 which signed their agreement in October 2007. These allocations were subject to change as new census data became available.

Table 5.2

Allocation of Funds (millions of $) from 2005 to 2010, by Province and Territory

When signing the agreements the provinces were free to choose the way the money would be allocated among their municipalities, and while there are some exceptions, they chose to allocate them essentially on a per capita, entitlement basis, with some minor adjustments to ensure that the smaller communities received a base amount. One of the exceptions is Nova Scotia, which created an allocation formula that gives municipalities a percentage of the total allocation depending on the number of their dwelling units, their population, and their five-year rolling average of standard expenditures. Another exception is British Columbia, which we discuss below.

In the spirit of a “flexible approach” and a “long-term solution” the signatories agreed on desired outcomes and eligible project categories, rather than earmarking the money for specific projects. As Godfrey explained, while it was important for the federal government to focus attention on a critical issue – environmentally sustainable municipal infrastructure – setting the criteria by which projects qualify for funding and allowing municipalities to set the individual priorities for those projects would avoid the problem of trying to satisfy everyone’s expectations and needs (CBC News 2004). The project categories, as well as examples, include

• Public transit. For example, rapid transit (tangible capital assets and rolling stock like light rail, subways, ferries, transit stations, and park-and-ride facilities), transit buses (bus rolling stock, transit bus stations), intelligent transport systems, and transit priority capital investments.

• Water. For example, drinking water supply, drinking water purification and treatment systems, drinking water distribution systems, and water metering systems.

• Wastewater. For example, systems including sanitary and combined sewer systems, and separate storm water systems.

• Solid waste. For example, waste diversion, material recovery facilities, organics management, collection depots, and waste disposal landfills.

• Community energy systems. For example, cogeneration or combined heat and power projects and heating and cooling projects.

• Capacity building. For example, collaboration (building partnerships and strategic alliances, participation, and consultation and outreach), knowledge (use of new technology, research, and monitoring and evaluation), and integration (planning, policy development and implementation).

• For communities of less than 500,000. Eligible projects include active transportation infrastructure like bike lanes, local roads, and bridges and tunnels that enhance sustainability outcomes.

Municipalities can use the funds to cover capital costs only and cannot use them for maintenance costs, operating costs, debt reduction, or replacement of existing municipal infrastructure expenditures. They can also bank funds and accrue interest. Large municipalities, defined as those with a population of five hundred thousand or more, are allowed to choose only two of the categories from the eligible list of projects.12 In addition, all municipalities are encouraged to pool resources with other municipalities to support projects and initiatives that can benefit the region.

SIGNATORIES AND MUNICIPAL RESPONSIBILITIES

• All signatories were required to sign a Funding Agreement with each municipality before the transfer of the funds.

• Municipalities were required to complete a Multi-Year Capital Investment Plan before the fourth year.

• Each province had to ensure that over the period 1 April 2005 to 31 March 2010 its average annual capital spending on municipal infrastructure and that of its municipalities would not be less than the Base Amount. The Base Amount is defined as the average of spending by the province and municipalities on municipal infrastructure for the five years preceding the signing of the agreements.

• Signatories must enforce penalties if a municipality is noncompliant with the terms and conditions. Penalties may include withholding, reduction, or return of payment and/or non-renewal of the agreement

• As previously explained, each municipality, or region, had to develop an Integrated Community Sustainability Plan as the basis upon which they would determine plans and priorities to aid in their achieving three environmental sustainability outcomes: reduced greenhouse gas emissions, cleaner water, and cleaner air.

• Municipalities must retain title to and ownership of the resulting infrastructure for the eligible projects for at least ten years after its completion.

• Fund recipients are required to deposit the contributions into a separate and distinct account.

REPORTING, AUDITS, AND EVALUATION REQUIREMENTS

Signatories are required to produce an Annual Expenditure Report and an Audit Report, and they must also agree to keep proper records about the use of the funds for three years after the completion of each project because the federal government might request an audit, which must be paid for by the signatory to any one or more projects.

For the purpose of assessing, among other things, the extent of the achievement of the program objectives, how the funds were used, and the effectiveness of the funding approach, in 2009 the signatories were required to complete a joint formative evaluation of the program with the federal government. The results of these joint bilateral evaluations were incorporated in a national evaluation that the federal government completed in the same year. In 2009, and periodically thereafter, signatories are also required to submit an Outcomes Report that measures results and outcomes of the program based on previously agreed indicators.

In the case of British Columbia and Ontario, there might be a Compliance Audit or/and a Performance Audit of the UBCM and AMO, who are responsible for implementing the agreement and allocating the funds to the municipalities in those provinces respectively. This audit would be conducted by the federal minister or the auditor general of Canada at their cost.

This regime of reporting and accounting reflects an attempt to balance several federal concerns. First, Ottawa was genuinely concerned to allow the recipients flexibility in their use of the funds to minimize “red tape”; they did not want to burden municipalities – especially the smaller ones – with a complex and detailed requirement to report on the use of the funds. Second, Ottawa wanted to ensure to the maximum extent possible that the funds would have a net positive impact on infrastructure investments. The conditions regarding “base” expenditures were to prevent provinces and municipalities from diverting their own funds away from these investments as a result of the gas tax program. And finally, in the wake of the sponsorship scandal, the government was determined to have a reliable accountability framework in place.

NOTABLE DIFFERENCES

While the agreements are, in the main, very similar across provinces with respect to terms and conditions, there are some notable differences, particularly in Ontario and British Columbia and to a lesser extent in Quebec.13

The Ontario provincial government, while a signatory to the agreement, chose not to be involved in the administration of the program and the management of the funds. That role was taken up by the Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO) for all jurisdictions other than the City of Toronto and by Toronto directly for the money it received. Several interviewees attributed this relative non-involvement by the province to an earlier provincial transfer program to the municipalities that became very contentious and to the desire of the government to avoid a repeat.14 Ontario’s signature on the agreement basically committed the government not to reduce its own grants to the provinces, but to little beyond that. Its detachment from the program raises concerns that the ability to co-ordinate the federal program with provincial programs having complementary objectives will be compromised.

Signing the agreement directly with Toronto also marked a new direction. The city was delighted to be the only municipal government in the country to be a direct signatory to a funding agreement, leaving the Ontario provincial government aside. The city receives its grants directly from the federal government (without funnelling through the province or the AMO) and reports on the use of the funds directly to the federal government. At least some in the city government and elsewhere believed and hoped – perhaps naively – this would mark a new start on direct federal interactions with urban governments.

That aside, the federal government’s acceptance of the AMO and the Union of British Columbia Municipalities (UBCM) as program administrators responsible for financial management and distribution and for reporting back to Ottawa marked something of a new departure in federal-provincial financial relations. The AMO is a nonprofit association of all Ontario municipalities (with the exception of Toronto, which quit the association in 2004). The UBCM is a similar organization that has represented the interests of all local governments in British Columbia since 1905. The UBCM, however, operates under an act passed by the Legislative Assembly of the province. These arrangements are notable in that non-governmental organizations are responsible for the administration of the federal transfers.

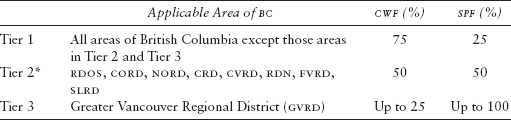

This agreement is also interesting because of the allocation processes that were chosen in some provinces. Most provinces allocated funds to the municipalities based entirely on population. In British Columbia, however, the allocation is more complex. Three tiers and three funds were designated. The tiers, set out in table 5.3, were created based on differing community characteristics, including population density, degree of urbanization, adjacency of communities to urbanized areas, and the need for intra-regional infrastructure. The three funds are

Table 5.3

Allocation of the Three Funds in British Columbia

* Tier 2 = Regional District of Okanagan-Similkameen, Regional District of Central Okanagan, Regional District of North Okanagan, Capital Regional District, Cowichan Valley Regional District, Regional District of Nanaimo, Fraser Valley Regional District, Squamish Lillooet Regional District

• Community Works Fund. This fund disburses funding directly to municipalities based on a percentage of the per capita allocation for local spending priorities and has a funding “floor” to ensure a reasonable base allocation of funds.

• Strategic Priorities Fund. This fund provides funding for strategic investments that are larger in scale or regional in impact. It was created by pooling a percentage of the per capita allocation. In the case of the Metro Vancouver, the board of directors requested that 100 percent of their per capita allocation be placed in this fund and be made available for transportation investments.

• Innovations Fund. This fund provides funding for projects and initiatives by eligible recipients that show an innovative approach to achieving the intended outcomes. It comprises up to 5 percent of the total Gas Tax Fund allocation for British Columbia.

Elements of the arrangement in Quebec are also distinct. The Quebec government was the only one to add additional funds ($383.6 million) to the federal contribution received by the municipalities, which represents 29.2 percent of the total allocation. Moreover, Quebec is the only province that required municipalities to add their own contribution. The rationale behind this decision was that municipalities needed to have a stake in the decision-making process, and Quebec believed that this contribution would encourage them to make prudent infrastructure investments.

The required municipal contribution is determined by taking into account the level of municipal investment to be maintained and by considering the minimum capital baseline in infrastructure reconstruction of $28 per resident per year applied under other Infrastructure programs (the Canada Québec Infrastructure Works Program 2000, the Québec Municipalities infrastructure programs, and the Municipal Rural Infrastructure Fund).

In Quebec, the government’s contribution is allocated over four years (2006–09) instead of the five years intended under the original agreement, and the funds are administered by the Société de financement des infrastructures locales du Québec (SOFIL). This organization was created with the sole purpose of contributing financial assistance to municipalities and of assisting in the implementation of their infrastructure projects. Under the agreements, SOFIL is also responsible for the reporting requirements.

While in every province the list of eligible projects is quite similar, Quebec decided to establish a list of work priorities, which are

1 Bringing drinking water and wastewater catchment and treatment equipment up to code. Municipalities must demonstrate that they do not need any projects under this priority before they can move to lower priorities.

2 Acquiring knowledge about the condition of pipes for drinking water and sewers (inventory, diagnosis, and action plan to renew the pipes).

3 Renewing pipes for drinking water and sewage. This priority, as well as number 2, does not apply to municipalities that do not have such pipes or that can demonstrate no need for renewal in the next ten years.

4 Repairs to and improvements to elements of the local road systems such as bridges or other municipal engineering structures and to municipal streets or other local roads.

In each of these three provincial variations it appears that the initiative arose within the province. The federal government was open to accommodating these variations because none of them affected the government’s core goals. In the case of the City of Toronto, however, the federal position was perhaps a bit more enthusiastic than passive permissiveness; at least some federal officials seemed to be intrigued by the direct federal–City of Toronto agreement, believing that it might open doors for future direct federal-municipal collaborations in a range of policy areas. In our view, however, while the Toronto agreement may be noteworthy, it is premature to herald the arrival of a new era in intergovernmental relations.

OTHER NOTEWORTHY FEATURES

The gas tax transfer is just one of many transfer payments (those for which the government receives no goods or services) made by the federal government each year. For example, in 2006–07 the transfers amounted to approximately $125 billion dollars (Public Works and Government Service Canada 2007). Of this, approximately $1.8 billion went to Infrastructure Canada, of which $590 million represented the gas tax transfer. This program is innovative in that it is a hybrid between a grant and a contribution. According to the current Policy on Transfer Payments, contributions are conditional transfer payments “for a specified purpose pursuant to a contribution agreement that is subject to being accounted for and audited,” while grants are unconditional transfer payments that “are not subject to being accounted for or audited but for which eligibility and entitlement may be verified or for which the recipient may need to meet pre-conditions” (Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat 2000).

The gas tax has some characteristics of a contribution agreement because it contains a complex accountability framework that includes an annual expenditure report, an outcomes report, and an audit report. At the same time, it has characteristics associated with grants because the funding is given up-front, and while the agreements specify eligible categories (like public transit, water and wastewater infrastructure, community energy systems, the management of solid waste, and local roads and bridges), the federal government is not involved in the selection of specific projects. Unlike grants the Gas Tax Fund was based on a five-year (2005 to 2010) formula, which required annual appropriations.

Based on these characteristics the Treasury Board ended up characterizing the Gas Tax Fund as an “other transfer payment,” which is defined as being “based on legislation or an arrangement which normally includes a formula or schedule as one element used to determine the expenditure amount; however, once payments are made, the recipient may redistribute the funds among the several approved categories of expenditure in the arrangement” (Treasury Board Secretariat of Canada 2000).

Before choosing this delivery mechanism the government explored other options (Infrastructure Canada, Cities and Communities Branch 2007). One was a contribution agreement that involved reimbursing the money for funds spent on projects through an application process. The perceived weakness of this approach was that it would not have solved the fiscal capacity problems facing municipalities. Another alternative was what was called a “vacating tax room,” which would have allowed the provinces to increase taxes and subsequently to increase available funds for the municipalities. The constraint of this approach was that it would have eliminated and/or limited the federal government’s ability to influence national interests arising in Canadian cities and communities. The last option considered was a trust fund, proposed by Finance, which involved transferring the money immediately to a special (off-budget) account from which it would be transferred to municipalities and/or provinces over the designated time period. In recent years, other federal programs – most notably the Canadian Foundation for Innovation – had been established in this manner. Because of the loss in control and the perceived inability to advance federal policy objectives, the INFC and Paul Martin were opposed to this option.

The final decision to choose the hybrid arrangement was based on issues of flexibility, constitutional responsibility, and accountability. The program was designed to achieve a balance among the following factors: (1) the concerns of Treasury Board and Finance Canada over the accountability mechanisms to monitor the use of the funds and to limit Ottawa’s financial commitment were satisfied; (2) the funds had to flow to the municipalities through provincial treasuries to respect constitutional jurisdictions;15 (3) municipalities were given the discretion to select their own projects; (4) municipalities were permitted to pool, bank, and borrow against their allocation to maximize the impact of the funding; and (5) the program was established to facilitate its extensions (and ultimately to make it a permanent program).

CONCLUSION

Aside from transferring resources to municipalities for much-needed infrastructure improvements, the gas tax program is of interest for a number of other reasons. While more definitive assessments must await further evidence, the program may be cited in future years as establishing some important precedents. First, the modified contribution agreement model may prove an attractive option for future federal-provincial fiscal arrangements. It is notable that the federal government was able to conclude agreements with all the provinces and territories without stirring up defensive reactions from the provinces seeking to protect their constitutional turf. Of course, the fact that Ottawa was distributing money without requiring any matching fiscal commitments from the recipients undoubtedly helped; free money is seldom unwelcome.

This approach essentially involves negotiating contracts with the provinces individually to fund a program of mutual interest. Because the contracts are individual, they open the possibility that each one could be substantially different from province to province, in order to meet specific needs, although as noted, it is interesting that in the case of the gas tax program, the contracts were remarkably similar across provinces. However, as also noted, there were some significant differences. This model also creates a means to conditionalize grants to the provinces without raising provincial concerns of jurisdiction, though whether these (or indeed any) conditions are binding on provincial spending decisions is open for investigation. The fact that a similar set of agreements were concluded by the Martin government in the field of child daycare suggests that the model may be more than a one-off set of arrangements for the gas tax. (The fact that the daycare agreements were cancelled when the Harper government came into office does not negate this point. They were cancelled because of the type of childcare arrangements they embodied, not because of the form of the agreement. Harper kept the gas tax agreements and later extended them.)

A second observation relates to the use of non-governmental organizations in Ontario and British Columbia as delivery vehicles for the distribution of funds and the accountability for the use of those funds. These agencies are not NGOs in the usual sense in that they are associations of municipal governments. But they themselves are not governments, and Ottawa’s placing them in such a central delivery role is an interesting development.

Third, a few comments are in order on the much misunderstood earmarking of funds. The federal gas tax funds are to be used only for infrastructure investment in approved areas and are not to displace provincial or municipal spending in these areas that would have occurred without the transfers. The agreements go to some lengths to try to ensure that this occurs. For example, in an attempt to ensure that provinces do not reduce their funding, there is a requirement that provincial grants to municipalities for infrastructure investment cannot fall below their levels in the five years before the gas tax program. In the cases of Ontario and British Columbia the ability to impose binding conditions on the use of the funds may be strengthened somewhat, because the money does not flow through the consolidated revenue funds of the provincial governments; the money is more easily tracked because it flows through the AMO and the UBCM respectively. However, as with all conditional grants programs, it is virtually impossible to ensure that there is a 100 percent incremental impact. The incremental impact on municipal infrastructure spending versus the displacement of provincial and/or municipal infrastructure spending that would have occurred in the absence of the federal grant is an important research and policy question.16

Finally, at least some federal political and bureaucratic officials believe (and hope) that this initiative has established a basis for future direct relationships between the federal government and the municipalities. At least in part this belief follows from the fact that the City of Toronto was a direct signatory to an agreement and that it reports directly to the federal government on the use of the funds. In part it comes from the series of consultations that Minister John Godfrey conducted with mayors and other municipal officials in the early stages of the process. And in part it comes from the linkage to the two municipal organizations that are serving as administrators in their respective provinces. In the view of some, the gas tax program has even opened a door to the eventual de facto recognition of a “third order” of government that can relate to the federal level much as provinces do now. In our view, this is reading too much into a more modest initiative. But it has opened a more focused federal policy commitment in relation to municipal issues, and that in itself is important. The gas tax initiative has also created expectations that municipal governments will be consulted on future infrastructure investments. But the fundamental nature of future federal-provincial-municipal relations is unlikely to change dramatically in the foreseeable future.

This chapter is in part based on a number of confidential interviews we conducted with individuals involved in the policy decisions and in the negotiations process leading to the gas tax fund agreements. We wish to thank them for their assistance without implicating any of them in our analysis or conclusions.

1 In 1996 nearly 78 percent of the Canadian population was living in urban areas, defined as communities with at least 1,000 inhabitants and with a density of at least 400 persons per square kilometre. More specifically, about 62 percent of Canadians were living in the 25 census metropolitan areas, also known as CMAs, which are city-regions with populations in excess of 100,000 (Bourne 2000).

2 As Andrew, Graham, and Phillips (2002, 10) argue, the “period since 1985 was characterized by the search of provincial-municipal disentanglement, which is defined as changes in provincial-municipal relationships.” This resulted in “significant downloading of responsibilities to municipalities without financial compensation and a sharp reduction in provincialmunicipal transfers,” which are one of the three main sources of revenues to municipalities (the other two are property taxes and user fees).

3 Among the significant players reinforcing these messages were the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) and its Big Cities Mayor Caucus (BCMC). For example, in 2001 the FCM released two key reports: Quality of Life in Canadian Communities (2001c) and Early Waning: Will Canadian Cities Compete? (2001a), and the BCMC launched a national campaign, Canada’s Cities: Unleash Our Potential.” Discussions were also supported by independent research institutes that held conferences, summits, symposiums, and published reports on urban issues. Among them were the Canada West Foundation, with its Western Cities Project, and the Canadian Policy Research Network (CPRN), with its Cities and Communities research stream. For a full list and access to all their publications on the subject see Canada West Foundation (2007), and CPRN (2008). Finally, another noteworthy contribution came from the TD Bank Financial Group with its report A Choice between Investing in Canada’s Cities or Disinvesting in Canada’s Future (2002).

4 One of the studies outlining the problem with the infrastructure stock was conducted jointly by the FCM and McGill University in 1996: Report on the State of Municipal Infrastructure in Canada. In this report, the national municipal infrastructure deficit was estimated at $44 billion, with the roads, bridges, and sidewalks being in the greatest need of repairs (FCM-McGill University 1996).

5 In particular, the report called for the appointment of a cabinet minister responsible for urban regions and the establishment of a long-term (i.e., fifteen-year) National Infrastructure Program that would build on current programs to provide stable, reliable funding (Sgro 2002). Moreover, it recognized the necessity for cooperation and collaboration between all players in the urban policy community and the interrelatedness of all urban problems and their solutions (Wolfe 2003). For the full report see Sgro (2002).

6 The EACCC was created to “help rethink the way Canada and its communities are shaped to ensure Canada will be a world leader in developing vibrant, creative, inclusive, prosperous and sustainable communities” (Deparment of Justice Canada 2008). Their final report was submitted to the prime minister on 15 June 2006.

7 As it was evident in a speech Martin delivered to the FCM, by 2002 he was still sceptical but receptive to the possibility of sharing the gas tax. In his remarks (2002) he explained that “the federal government has always been wary of dedicated taxes – arguing that such ties make it very difficult, if not impossible, to respond to changing circumstances,” but that recognizing “that municipalities have inadequate revenue sources as things stand” he knew he needed to be open to considering all options.

8 This department brought together the Cities Secretariat, which was located at the Privy Council Office; Infrastructure, which was on its own; and four Crown corporations. At the time of his appointment as minister of state, Godfrey (2004b) candidly remarked that this was “a combination of steak and sizzle.” While Infrastructure had the money, the programs, and the expertise on the ground, the Cities Secretariat had done a good job in scoping out the potential for a gas tax deal and improved, tripartite, respectful relationships (Godfrey 2004b).

9 This summit was the perfect setting for the announcement, since it was attended by, among others, mayors, councillors, other elected officials, and municipal employees such as chief administrative officers, city clerks, and municipal managers. The title for this summit was Developing Proven Governance Practices to Encourage Public Confidence.

10 Many provinces have drafted guides and templates to help their municipalities with their ICSPs. They are a great source for better understanding what the process of creating them entails and what their goals are. For an example see Service Nova Scotia and Municipal Relations (2007).

11 While First Nations communities in the three territories receive funding through the federal-territorial Gas Tax Fund agreement, in October the federal government created the First Nations Infrastructure Fund (FNIF), which was open to First Nations communities in the ten provinces. The agreement was signed by the Honourable Chuck Strahl, minister of Indian affairs and northern development and federal interlocutor for Métis and non-status Indians; the Honourable Lawrence Cannon, minister of transport, infrastructure and communities; and the Assembly of First Nations regional chief (Yukon), Rick O’Brien. This five-year program, with $131 million in funding, used a combination of funds from existing federal funding sources: the First Nations component of the Municipal Rural Infrastructure Fund; the First Nations component of the Gas Tax Fund; and the Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program. For more information see Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (2009).

12 The objective of this clause was to discourage large municipalities from stretching the funds over too many project categories, resulting in less transformative investments. Our research has shown that most large municipalities (such as Calgary, Edmonton, Vancouver, and Toronto) have chosen to use all their gas tax allocation for transportation expenditures.

13 For Ontario see the Agreement for the Transfer of Federal Gas Tax Revenues under the New Deal for Cities and Communities, Canada-Ontario-Association of Municipalities of Ontario-City of Toronto (2005–15). For British Columbia see Agreement for the Transfer of Federal Gas Tax Revenues under the New Deal for Cities and Communities, Canada-British Columbia-Union of British Columbia Municipalities (2005–15). For Quebec see Guide on the Revised Terms and Conditions of the Transfer to Québec Municipalities of a portion of federal gasoline excise tax revenues and the Government of Quebec’s contribution to municipal infrastructure.

14 In 2004 the newly elected government of Ontario proposed a transfer of two cents of the existing provincial gas tax to municipalities for public transit investment. In order to determine the allocation formula the government consulted with the AMO. The two options presented for the allocation of provincial gas tax revenues were based on population, supported by the AMO and most municipalities, and on transit ridership, strongly supported by Toronto. In the end, after difficult negotiations a compromise was reached and the formula took both elements into account. This disagreement contributed to David Miller’s decision to take Toronto out of the AMO. He believed that an organization that represents small towns cannot speak for Canada’s largest city (Swift 2004).

15 As discussed above, in the case of Toronto, Ontario signed the agreement that allowed the city funding to come directly from the federal government.

16 An analysis of the program by Adams (2012) found, inter alia, that gas tax funds did not displace infrastructure investment that would have occurred in any event.

REFERENCES

Adams, Erika. 2012. “Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Investment Decisions and Outcomes: The Case of the Gas Tax Fund in Ontario.” PhD diss., Carleton University, Ottawa.

Anderson, George. 2002. “Cities and the Federal Agenda.” Horizons – Policy Research Initiative 5 (1): 4–6.

Andrew, Caroline. 2001. “The Shame of (Ignoring) the Cities.” Journal of Canadian Studies 35 (4): 100–11.

Andrew, Caroline, Katherine A. Graham, and Susan D. Phillips. 2002. “Introduction: Urban Affairs in Canada: Changing Roles and Changing Perspectives.” In Urban Affairs: Back on the Policy Agenda, edited by Caroline Andrew, Katherine A. Graham, and Susan D. Phillips, 3–22. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Bourne, Larry. 2000. “Urban Canada in Transition to the Twenty-first Century: Trends, Issues, and Visions.” In Canadian Cities in Transition: The Twenty-First Century, 2d ed., edited by Trudy Bunting and Pierre Filion, 26–51. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Canada West Foundation. 2007. “Western Cities Projects.” Accessed 22 April 2009, Canada West Foundation website, http://www.cwf.ca/V2/cnt/proj_western_cities.php.

Canadian Policy Research Networks. 2008. “Cities and Communities.” Accessed 21 May 2009, http://www.cprn.org/theme.cfm?theme=26&l=en.

CBC News. 2002. “Martin Wants New Deal for Cities,” 31 May. Accessed 10 January 2008, http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2002/05/31/martin_municipal020531.html.

– 2004. “Mayor Bends Ottawa’s Ear on ‘New Deal’ for Cities,” 14 January. Accessed 10 January 2008, http://www.cbc.ca/canada/manitoba/story/2004/01/14/mb_mayor20040114.html.

Clarkson, Adrienne. 2004. Speech from the Throne to Open the Third Session of the 37th Parliament of Canada. Ottawa: Goverment of Canada.

Department of Finance Canada. 2004. Budget 2004 –Budget Plan, chap. 4, “Moving Forward on the Priorities of Canadians.” Accessed 21 May 2009, http://www.fin.gc.ca/budget04/bp/bpc4d-eng.asp.

– 2005. Budget 2005: Delivering on Commitments.

Deparment of Justice Canada. 2008. “Constitution Acts 1867 to 1982,” 24 November. Accessed 30 November 2008, http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/const/.

Direction des infrastructures, Ministère des Affaires municipales et des Régions. 2006. Guide on the Revised Terms and Conditions of the Transfer to Québec Municipalities of a Portion of Federal Gasoline Excise Tax Revenues and the Government Of Québec’s Contribution to Municipal Infrastructure. Quebec.

Federation of Canadian Municipalities. 2001a. Early Waning: Will Canadian Cities Compete? Ottawa.

– 2001b. Federal Budget Submission. Ottawa.

–2001c. Quality of Life in Canadian Communities. Ottawa.

Federation of Canadian Municipalities –McGill University. 1996. Montreal: The Federation of Canadian Municipalities and the Department of Civil Engineering and Applied Mechanics, McGill University.

Godfrey, John. 2004a. Address to the Annual Conference of the Association of Municipalities, 24 August.

– 2004b. “Keynote Address to the Canadian National Summit on Municipal Governance,” 28 July. Accessed 20 May 2009, http://web.archive.org/web/20041122113416/www.infrastructure.gc.ca/speeches-discours/20040728_e.shtml.

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. 2009. First Nations Infrastructure Fund. Accessed 21 October 2009, http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/ai/scr/bc/proser/fna/infdev/fnif/index-eng.asp.

Infrastructure Canada. 2008. Agreement for the Transfer of Federal Gas Tax Revenues under The New Deal For Cities and Communities. Canada-Bristish Columbia –Union of British Columbia Municipalities (2005–15). Accessed 20 January 2009, http://www.infc.gc.ca/ip-pi/gtf-fte/agree-entente/agree-entente-bc-eng.html.

– 2006, 18 August. Mandate. Accessed 10 January 2008, http://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/eaccc-ccevc/about-apropos/mandate_e.shtml.

Infrastructure Canada, Cities and Communities Branch. 2007. Ottawa: Infrastructure Canada.

Martin, Paul. 2002. “Healthy Cities Vital to Canada’s future.” 16 (2): 32.

Mohammed, Adam. 2002. “Martin Says No to Mayors on Gas Tax: Collenette, Finance Minister Disagree Over Plan.”, 19 February, A1.

Planning for Sustainable Canadian Communities Roundtable. 2005. “Integrated Community Sustainability Planning,” 23–24 September. Accessed 12 March 2008, http://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/communities-collectivites/conf/documents/icsp-discussion_e.shtml.

Public Works and Government Service Canada. 2007. “Public Accounts of Canada.” Accessed 20 April 2008, http://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/recgen/txt/72-eng.html.

Randa, Lorne. 2001. “Prime Minister’s Caucus Task Force on Urban Issues Announced.” 9 May. Accessed 21 March 2008, http://www.nben.ca/environews/alerts/alert_archives/01/urban_e.htm.

Service Nova Scotia and Municipal Relations. 2007. “Integrated Community Sustainability Plans Municipal Funding Agreement for Nova Scotia.” Accessed 23 October 2009, www.gov.ns.ca/snsmr/muns/infr/pdf/ICSP_2007.pdf.

Sgro, Judy. 2002, November. “Final Report of the Prime Minister’s Caucus Task Force on Urban Issues: Canada’s Urban Strategy: A Blueprint for Action.” Ottawa.

Swift, Nick. 2004. “Toronto Mayor Demands,” 10 February. Accessed 20 October 2009, http://www.citymayors.com/politics/canada_citydeal.html.

TD Bank Financial Group. 2002. TD Economics Special Report.

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. 2000. “Policy on Transfer Payments,” 1 June. Accessed 10 January 2008, http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pubs_pol/dcgpubs/TBM_142/ptp1_e.asp.

Wolfe, Jeanne. 2003. “A National Urban Policy for Canada? Prospects and Challenges.” 12 (1): 1–21.

World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987. Published as Annex to General Assembly document A/42/427, Development and International Co-operation: Environment.