Institutional Arrangements and Planning Outcomes: Inter-agency Competition on the Toronto Waterfront

Many factors affect urban land use outcomes. The literature emphasizes the impact of successive planning models and processes, with particular attention presently going to ways of achieving effective public participation. It also underscores the role of economic and political power. In this chapter we concentrate on a factor that is often underplayed – the effect of the institutional set-up. By bringing an institutional perspective to the study of planning, the chapter attempts to correct the lack of attention this field has given to the role of agencies. Indeed, land use planning is among the disciplines that have least heeded the effects of institutional structures.

The object of study is the redevelopment of the Toronto waterfront. The focus on institutions is consistent with the nature of the case, for inter-agency rivalry has been central in the determination of planning outcomes on the Toronto waterfront, eclipsing other influences on land use. The involvement of all three levels of government (especially the federal and municipal levels) and the agencies they have spawned account for the crowded and conflicting agency field characteristic of the Toronto waterfront. In this sense, our case represents an extreme illustration of the impact the institutional set-up can have on urban planning. Still, it helps bring to light, albeit in a somewhat exaggerated fashion, a factor that is always present in land use planning.

We construct a narrative of waterfront redevelopment with a focus on factors responsible for a highly fragmented pattern of development and the frequent predominance of short-term profitability over public access and coordinated planning. The narrative covers nearly one-hundred years of waterfront history: from 1911 to 2008. It echoes the dominant view that the redevelopment of the Toronto waterfront has lived up neither to expectations of Toronto residents nor to successful examples from other urban areas (Chicago immediately comes to mind). We then rely on institutional theory to interpret this narrative and examine conditions that could have resulted in more positive outcomes. Consistent with the object of the Public Policy in Municipalities project, we give importance to issues related with multilevel governance, especially conflicting relations between the federal government and the City of Toronto.

The chapter unfolds in three main stages. It first introduces the literature on institutionalism theory and its planning variant, and then presents a historical narrative of the Toronto waterfront redevelopment. It ends with an interpretation of this history from an institutionalism theory framework. The study is relevant at two levels. It represents a rare application of institutional theory to the field of planning and provides a fresh interpretation of the Toronto waterfront case.

INSTITUTIONALISM AND PLANNING OUTCOMES

The adoption of the perspective of institutionalism theory flows largely from the nature of the case under study. The historical narrative of the development and redevelopment of the Toronto waterfront indeed reveals a chain of conflicts opposing agencies with clashing mandates and visions, yet often with overlapping jurisdictions. Planning outcomes on the Toronto waterfront mirror these conflicts. But the choice of an institutionalist perspective also rests on factors not specific to the case study: the ubiquity of institutions and their universal importance in the shaping of policies and their outcomes.

Institutions are defined broadly as organizations and formal codes of conduct (such as constitutions, laws, and rules), both responsible for a patterning of behaviour (Greenwood et al. 2008, 32; Scott 1995, 33). The traditional approach to institutions was primarily descriptive. It mostly concerned itself with a portrayal of political institutions and constitutions and the policy implications of different forms of government – presidential vs. parliamentary, for example (Clingermayer and Feiock 2001; McCabe and Feiock 2005; Weaver and Rockman 1993).

On a broader scale, fundamental features of governments, notably their dependence on votes and fiscal entries, have been invoked to account for the main orientations of policy-making. The impact of fiscal dependence on municipal policy has been highlighted by Peterson (1981) to explain foremost local concern for economic development and by Burchell and Listokin (1978) in their depiction of fiscal zoning. In these views, by virtue of their dependence on property taxation revenues, municipal administrations have a vested interest in land development. At the same time, however, because of the electoral process they must heed the reaction of the public to development.

Rebranded as the “new institutionalism,” the approach has branched out in different directions. It has, for example, examined the role of fields of knowledge favouring the spread of organizational features and practices across institutions. Lately, studies have also concentrated on how organizations socialize individuals to their values and shape their behaviour through rules and incentives (Hall and Taylor 1996; Peters 1996, 2008; Powell and DiMaggio 1991). Researchers adhering to normative explanations of behavioural control focus on the adherence of individuals to the values and norms of organizations to which they belong and on the resulting effects on the actions of these individuals (March and Olsen 1996). On the other hand, proponents of rational choice emphasize personal utility maximizing choices made within organizations’ systems of rules and incentives (Downs 1967; Horn 1995; Weingast 2002). Either way, convergence between the interests of individuals and those of the organizations to which they belong and consistency in the behavioural patterns of their members make it possible to perceive organizations as agents in their own right (Epstein and O’Halloran 1999; Jones 2001, 22; Wildavski 1987).

What is more, new institutionalism draws on the path dependency approach to address the long-lasting nature of many institutions and the uneven influence of decisions determining their form and function (Krasner 1984; Steinmo, Thelen, and Longstreth 1992). In accord with the tenets of path dependency, decisions taken in the formative stage of an institution are deemed to have a disproportional influence on its evolution because they are embedded from the start at the core of its structure (Peters 2005, 61; Pierson and Skocpol 2002; Skocpol 1992). And institutions and the patterned behaviour they foster endure by virtue of the capacity of organizations to socialize individuals to their values and the existence of positive feedback loops grounded in powerful institutional inducements, which reinforce actions compatible with the interests of institutions (Pierson 2000, 492).

By underscoring the patterned behaviour and path dependency features of organizations, new institutionalism can be perceived as giving excessive weight to stability at the expense of change (Peters 2008, 4; Pierre, Peters, and King 2005). The conceptual apparatus of institutionalism is poorly suited to explanations of transformations within existing institutions and even more so to explanations of the emergence and disappearance of institutions. Discussions of the consequences of organizational behaviour patterning and path dependency must account for the existence of factors of change. First, individuals within organizations are not mere automatons, an observation at the core of Anthony Giddens’s structuration theory, which portrays individuals as possessing practical consciousness allowing them to pursue their personal interest within structures, including organizational structures (Giddens 1984, 3, 22; Sewell 1992). The structuration theory view of the relation between agency and structure is thus consistent with the rational choice perspective. As they navigate the conditioning systems of organizations, all the while keeping an eye on their personal interests, individuals can have a transformative effect by giving more attention to certain incentives and penalties than to others, and going so far as to intentionally propel organizations in new directions. Organizations are also affected by social and technological innovations, along with emerging values. Finally, inter-organizational relations, either of a cooperative or of a competitive nature, inject a great deal of uncertainty in the evolution of organizations. Organizations must legitimate their existence and expansion by formulating visions of society that advance their self-interest (Deephouse and Suchman 2008). But in doing so, they confront other organizations deploying similar strategies. Interinstitutional settings are therefore a source of relativity and instability in the perception of social issues and the framing of solutions (Thornton and Ocasio 2008, 104).

All these factors of change point to the fact that path dependency is not written in stone. While there is clearly a tendency towards path dependency within institutions that fosters durability, existing organizational structures can be replaced owing to a loss of functionality and of their capacity to advance the interests of individuals operating within them, resulting in intense pressures for institutional transformation. Alternatively, the appearance of more effective organizational forms stimulates institutional entrepreneurship (DiMaggio 1988; Peters 2005, 17).

Because of the ubiquity of organizational structures, the focus on institutions does not so much challenge other perspectives on planning outcomes as add an additional layer of understanding. There is an institutional side to all social phenomena. For example, within this chapter’s sphere of interest, the planning literature pays much attention to the decision-making process in an attempt to enhance inclusivity and achieve outcomes that are more socially equitable. Case studies link different types of processes to different outcomes (Fainstein 2000; Forester 1989; Healey 1999). The institutional dimension of studies of planning processes is evident. The range of possibilities regarding the configuration of planning processes, such as their inclusivity, is dictated by the interests and values of the organizations in which they are embedded, hence the legendary conflicts between planners and their political masters. In addition, processes themselves can be seen as institutional conditioning environments that can pattern behaviour in order to reach their objective.

Political science and sociology focus on two coalitions of interests whose intent is to influence urban development. These coalitions occupy opposite ends of the political spectrum. Social movements consist of groups of citizens who would otherwise have insufficient political or economic clout to successfully pressure governments for more equitable urban policies, including planning interventions (Castells 1983; Hamel, Lustiger-Thaler, and Mayer 2000; Magnussson 1996). The other coalitions, the object of the urban regime perspective, are composed of elite groups with an interest in the redevelopment of downtowns in fashions that appeal to tourists and middle- and upper-class residents (Lauria 1996; Orr and Johnson 2008). Institutional considerations are inherent in the existence and effectiveness of these coalitions. Coalitions must be able to organize in a fashion that elicits positive responses from governments, essentially by stressing electoral and fiscal rewards likely to accrue from positive responses to their demands.

Social forces are present throughout the narrative. Political parties and coalitions changed, the expression of public opinion regarding the waterfront took different forms, citizen groups targeted specific issues, and developers had considerable influence on the form redevelopment took. But the focus is on the role of governments and agencies, a perspective justified by their predominant role in the redevelopment of the waterfront. The influence of social forces is thus perceived through the evolving institutional structure of the Toronto waterfront.

This chapter is guided by questions stemming from the institutional perspective which structure its investigation of the Toronto waterfront redevelopment process. It considers the circumstances that account for the prominent role of agencies in determining planning outcomes. It also verifies how initial orientations given to agencies persist and how agencies evolve. Finally, the case study brings to the fore the effects of competition between agencies, each with its own discourse and strategies mirroring its self-interest.

METHOD

Our Toronto waterfront narrative covers the evolution of the sector over approximately one hundred years – from the early twentieth century until 2008, the end of our research project on the Toronto waterfront. It relies on different sources. We consulted planning documents pertaining to the district, as well as Globe and Mail and Toronto Star articles over a forty-year period. More than two thousand articles concerning the redevelopment of the Toronto waterfront were identified. Although subject to biases, newspaper articles are well suited to the construction of a chronology of events. We also scanned the academic literature to identify previous research work dealing with the Toronto waterfront. Finally, we conducted seventeen face-to-face interviews with present and former members of parliament, heads of development agencies and urban planners. These were semi-structured interviews addressing policy-making, intergovernmental relations, social forces, and policy evaluation. Each one lasted approximately one hour.

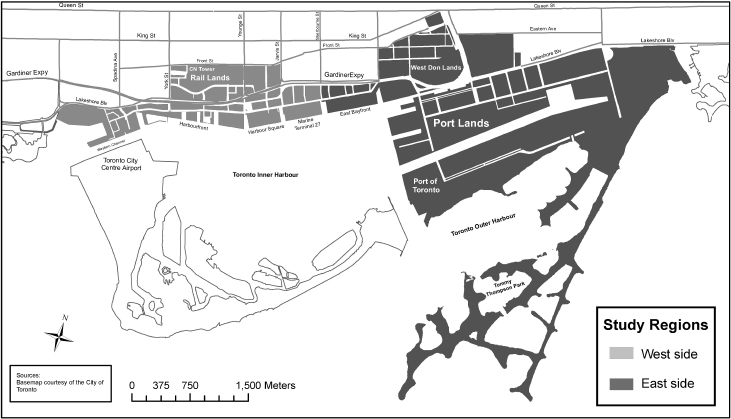

We investigate a 6.5 kilometre stretch of the Toronto waterfront, running from Leslie Street to the east to Stratcham Avenue to the west. This portion of the waterfront runs along downtown and inner-city Toronto and is or was occupied by port, industrial, railway, and airport functions. Much of it has been redeveloped, and most of the remaining land is either presently experiencing redevelopment or is the object of planning to this effect.

TORONTO WATERFRONT REDEVELOPMENT

This account of the Toronto waterfront redevelopment is divided into three phases. The first provides a historical background by describing the major development trends that unfolded during the port-industrial period, which lasted until the late 1950s. Given the focus of the narrative on redevelopment, more attention is given to the second and third phases, which both deal with efforts at transforming the waterfront into a post-industrial environment – the nature of which was a constant object of contention over these two phases. The second phase is characterized by tensions between widely diverging concepts for a redeveloped post-industrial waterfront, some of which were inspired by the ambitious modernist tendencies of the time. The period was also marked by stark discrepancies between grand planning visions and local projects driven by the short-term interests of competing agencies responsible for Toronto waterfront redevelopment. The third phase is distinguished by attempts at coordinating Toronto waterfront redevelopment around long-term planning strategies. These efforts illustrate difficulties in reaching large-scale planning objectives in a fragmented institutional environment. The phase is marked by success in achieving coordination despite the enduring presence of activities and developments that jar with mainstream Toronto waterfront planning.

The narrative describes the involvement of the three levels of government on the waterfront, mostly that of the federal and municipal levels, whose role has been most important. It expresses differences in their interventions associated with their respective perspectives on, and interest in, the waterfront. By also considering the agencies that were created by the different levels of government, the narrative takes a broad institutional perspective on the redevelopment of the waterfront.

The Port-Industrial Phase: 1911 to the 1960s

We begin the narrative in 1911, the year the Toronto Harbour Commission (THC) was set up. Responding to pressures from the Toronto Board of Trade for improved port facilities, the federal government gave ownership of approximately 80 percent of the waterfront to the THC (Schaeffer 1974; Toronto Harbour Commission 1912). Mandated to expand port facilities, the THC was also given responsibility for land reclamation and industrial development on the waterfront. While benefiting from start-up funding from the federal government and the City of Toronto, the THC was expected to achieve financial autonomy by relying on debentures and the creation, selling, or leasing of industrial land to raise the money needed for the improvement of the port (Canada 1911; Merrens 1998, 96). In the 1912 THC plan, the Dominion was to provide $6.1 million for “construction of seawalls, breakwaters, circulating channels and channel bridges” (Mellen 1974, 334). The city, for its part, was to allocate $3.27 million for roads and bridges, and the THC was to spend $11.2 million for the reclamation of land and construction of harbour facilities. The commission was given authority to issue debentures and to recover its costs through land sales. Although officially a federal agency, the THC was in reality controlled by the City of Toronto, which appointed three of its five board members. Typically, board members consisted of the mayor of Toronto, council members, and local business people, mostly sponsored by the Board of Trade. The federal government was content to take a hands-off approach to the THC, even if its jurisdiction over the agency allowed it to alter its mandate (Ircha 1993).

The main achievements of the THC include some industrial development in the area under its jurisdiction; extensive land filling, much of it leading to the creation of the Leslie Spit (a jetty extending 4.65 km into Lake Ontario); and the opening of the Toronto Island Airport in 1937 (see figure 6.1). But its major project, the creation of an outer harbour on both sides of the Leslie Spit, never materialized.

Over its entire existence, the THC had to contend with limited port activity, since the scope of the Toronto port remained regional rather than national. It was hoped that the 1958 opening of the St Lawrence Seaway would increase traffic to the port by making it accessible to sea-faring vessels. Not only did these expectations fail to materialize, but the port was further marginalized when containerization took hold a few decades later (Booz-Allen and Hamilton 1992; Ramlalsingh 1975, 53). The THC industrial strategy also met with little success. The Toronto waterfront mostly attracted low-value, land-hungry industrial facilities, such as concrete works, coal yards, and oil refinery and storage, and from the 1950s waterfront industrial land had to face intensifying competition from suburban industrial sites offering superior highway accessibility at a time of increasing reliance on truck transportation (Lemon 1990, 16). By the mid-1960s, the financial arrangements intended to secure THC support for the port were no longer workable. Declining port activity required rising financial support at a time when it was becoming increasingly difficult to generate revenue from Toronto waterfront industrial land; hence, THC’s renewed efforts at land disposal to raise funds despite a climate of dwindling demand for inner-city industrial sites (Desfor 1993). The THC adapted by retargeting its land sale at non-industrial activities (RCFTW 1989a, 47).

Figure 6.1 Toronto Central Waterfront.

Source: Basemap courtesy of the City of Toronto

Divergent Efforts at Post-Industrial Redevelopment: 1960s to the 1990s

The transition to the post-industrial phase of the Toronto waterfront can be traced back to the late 1950s, when the City of Toronto began exploring redevelopment concepts for the sector. But one has to wait until 1972 to witness the launching of the first large-scale post-industrial project on the waterfront.

Many factors converged to bring about a shift in waterfront redevelopment. We have just noted the lacklustre performance of the port and the limited interest in adjacent industrial land, which compelled the THC to seek alternative development to generate the revenues it needed to operate. At the same time, the downtown was enjoying accelerated growth, which raised the profile of nearby waterfront land. Another factor was federal interest in urban matters, reflected primarily in the active role the Central (now Canada) Mortgage and Housing Corporation played in suburban development and urban renewal, and the setting up in 1971of the Ministry of State for Urban Affairs (Bacher 1993; Miron 1993; Wolfe 2003). The 1960s and early 1970s also marked the apex of expert-driven modernist planning, riding a wave of economic prosperity and technological advancement and yielding highly ambitious plans that broke with traditional patterns of urban development. And finally, a purely functional perception of the city was challenged by perspectives that underscored its cultural and recreational dimensions. Nowhere was this transition more obvious than along the waterfront of North American cities. Areas that had been given exclusively to port facilities, industrial uses, railways, and expressways were taken over by residential, cultural, and recreational functions. In Canada the change of perspective on waterfronts was epitomized in the late 1960s and early 1970s by Expo 67 in Montréal and Ontario Place in Toronto (immediately to the west of our study area).

A series of modernist waterfront redevelopment schemes were formulated over the 1960s. In the early 1960s the City of Toronto departed from its commitment to a waterfront that was focussed on port and industrial activities and came up with a scheme consisting of decks, plazas, and low-rise industrial structures at water’s edge (Toronto Planning Board 1962). In 1961, Metro Toronto engaged in a complex planning process for the waterfront involving the City of Toronto and its agencies, the federal government, the province, the THC, railway companies, boating committees, and conservation councils (Metropolitan Toronto Planning Board 1967). The THC played a key role in the process, given its responsibility for the delivery of the final plans for the City of Toronto portion of the waterfront. Proposals for this part of the waterfront appeared in 1968 in a document entitled A Bold Concept for the Redevelopment of the Toronto Waterfront (Toronto Harbour Commission 1968). There were three core elements in the plan: the creation of an outer harbour, the relocation of the Island Airport, and the development of a new residential community on the former airport land (Desfor 1993). Revenues accruing from this residential development were essential to the achievement of the other facets of the plan, but in the end, nothing came of it. Moving the airport was ruled out by flight paths that would cross those of the Toronto International (now Pearson) Airport and the vigorous opposition of residents of the gentrifying Beach neighbourhood, which would have been close to the relocalized airport (Hodge 1972). Finally, with the low shipping traffic of Toronto, there was little need for a new outer harbour.

In the early 1970s the City of Toronto engaged in another waterfront planning effort whose purpose was to provide a vision for the entire district and coordinate the activities of the different waterfront agencies (Toronto Planning Board 1974). The process was complex, involving dozens of waterfront stakeholders and in the end was bypassed by projects put forth by agencies (Desfor, Goldrick, and Merrens 1989, 492).

Most ambitious of all was the Metro Centre plan, which was carried out by the Canadian National and Canadian Pacific railway companies to provide a redevelopment framework for their land holdings between Front Street and the Gardiner Expressway. In 1970 the plan was submitted to the City of Toronto, which approved it without giving much attention to its consistency with other plans for the waterfront. Metro Centre plan proposals were futuristic: office and residential towers set on podiums, diagonal street patterns, the world’s highest tower, a massive pyramid, and the replacement of Union Station by office towers (Community Development Consultants Ltd 1968; Greenberg 1996; Metropolitan Toronto Planning Board 1970). As could have been expected, the proposed demolition of Union Station triggered massive opposition. What is more, the market for core area offices and housing could not have sustained the office and residential space the Metro Centre plan allocated to the railway lands. Ultimately, among all the proposals contained in the plan only the CN Tower was erected.

The Toronto waterfront vision that most resonated with the public was a 1972 federal Liberal Party electoral promise to create a large park on the central portion of the waterfront (Gordon 1994; McLaughlin 1992). We will see that as in the case of most proposals for the waterfront, the park was not realized.

When redevelopment did take off, little heed was given to the grand vision of the plans. The first redevelopment project was Harbour Square, which occupied a site between Queens Quay West and the water edge, and Yonge Street and York Street (Globe and Mail, 27 July 1963; 4 September 1965) (see figure 6.1). The project was designed and promoted by a developer with strong ties with the federal government. City council, then dominated by a prodevelopment caucus, and the THC approved the project despite its lack of conformity with the City Waterfront plan (Toronto Star, 10 April 1969). Work on the project consisting of a hotel and two large luxury condominium buildings began in 1972. The public reacted negatively to the project, lamenting its upmarket nature and insufficient public space.

In a sense, Harbour Square foreshadowed the Harbourfront project, a much larger scheme that was to affect a substantial portion of the waterfront. In both cases the federal government was involved in launching the projects. Over approximately twenty years, most of the attention on the waterfront focussed on Harbourfront, which covers the area from York Street to Bathurst Street and from the Gardiner Expressway to the water’s edge (see figure 6.1). The idea of a park on the waterfront evolved into a mixture of public spaces and cultural activities, whose funding was to originate from on-site commercial and residential development (Toronto Star, 9 February 1979). Responsibility for the development of Harbourfront was first given to the Ministry of State for Urban Affairs, which failed to launch the project. In 1976, the Federal Government created the Harbourfront Corporation and mandated it with the development of Harbourfront (Gordon 1994). There were nine members on its board: two appointed by the City of Toronto, two by Metro Toronto, and the remaining five by the federal government, with the approval of the city and Metro (Globe and Mail, 25 May 1976). The board included high-ranking executives from the City of Toronto and Metro. Federal appointments were replaced when parties in power changed.

The original vision of Harbourfront harmonized several objectives. It would provide ample public space, run an active cultural program and provide retailing and mixed-income housing. The goal was to create a vibrant district with “an all day, year-round population” (Harbourfront Corporation 1978, 7). A conceptual rendering showed low- and mid-rise buildings (with less than eight stories) in a park-like environment (Toronto Star, 24 March 1977). During the 1979 electoral campaign, the federal Liberals pledged full funding of Harbourfront based on the then prevailing concept (Globe and Mail, 31 March 1979). The victorious Progressive Conservatives praised the Harbourfront concept but expressed concern over its high cost (Toronto Star, 7 October 1979). City council was also favourable, largely because 30 percent of the housing was to be subsidized. It was quick to approve the secondary plan for Harbourfront, even though doing so short-circuited a previous effort to involve the different waterfront agencies in the formulation of a comprehensive plan for the entire waterfront (Toronto Planning Board 1974; Toronto Planning Department 1980). When they returned to power in 1980 the federal Liberals committed $25 million to Harbourfront but made it clear that this would be the only federal government contribution and that the remaining $200 million needed for the operation of Harbourfront was to originate from private investments (Globe and Mail, 14 June 1980; Toronto Star, 13 June 1980).

Initially, expectations for Harbourfront ran high. The secondary plan outlined moderate densities and generous green space allowance, and former city planners took the helm of the development process (Globe and Mail, 24 June 1980; Toronto City Council 1982). But things soured as Harbourfront was confronted with two problems: difficulty in meeting assisted housing targets and over-development owing to the need to generate revenue to support cultural programming. As the federal Progressive Conservative government slashed spending on the construction of affordable housing in the mid-1980s, it became difficult for Harbourfront to meet its affordable housing targets. The Harbourfront Corporation was criticized for its use of a broad definition of affordable housing and for the poor appearance of a large low-cost housing development called Harbour Point (Globe and Mail, 8 April 1986).

The Harbourfront Corporation was also chastised for an accelerated development process, which took place at the expense of design principles and open space objectives (Globe and Mail, 18 March 1987). Visitors and residents alike considered the density to be too high (Globe and Mail, 23 April 1986). Things came to a head when Harbourfront categorized small residual spaces surrounding buildings as open space, causing the city’s Park Commission to call for a stoppage of development (Gordon 1994, 6–33; Toronto Star, 2 January 1987). Ultimately, Harbourfront development was frozen by the City of Toronto and the federal government while they performed reviews, and in 1990 the province imposed its own moratorium. Deprived of revenues originating from new development, Harbourfront could no longer fulfill its mandate and was disbanded in 1990.

While criticized for the intensity of its development and for an approach to land use that was driven by a need to raise funding for its cultural programs, Harbourfront at least followed land use planning guidelines. The same could not be said of the approach to development taken by the THC. Required to support financially the port, whose declining activity deepened its operational deficit, the THC was selling or leasing its land for diverse development projects (RCFTW 1989a, 47). The main one was the World Trade Centre, consisting of two towers with twenty-five and eighteen storeys respectively, but there were also industrial and retailing developments (Globe and Mail, 2 December 1986). The development promoted by the THC was criticized both for its financial, rather than planning, motivation and for its hodgepodge configuration (Hartmann 1999; RCFTW 1990, 202–3). Overall, the THC resisted attempts at cooperation from the city and other agencies involved with waterfront redevelopment and objected to planning-related restrictions on development on its land (Desfor 1993, 174). Tensions between the city and the THC may seem surprising, because a majority of its board members were city council members. But in reality they did not necessarily espouse the views of the then ruling caucus at City Hall. Also it was observed that councillors appointed to the THC changed their positions as they moved between city council and the THC Board. Alleged improprieties in the sale of a lot at the foot of Yonge Street and refusal by the THC to renegotiate the deal blackened its reputation in the media and came to symbolize problems with an organization that appeared to lack checks and balances (Globe and Mail, 30 August 1986; Toronto Star, 28 August 1986; 29 August 1986).

Meanwhile, little development was taking place on the railway lands, notwithstanding the construction of the CN Tower between 1973 and 1976, of the Toronto Convention Centre between 1982 and 1985, of the Sky Dome (later renamed Rogers Centre) between 1986 and 1989. Railway companies were vying to maximize the office development potential of their land, but their requests met with resistance from the City of Toronto. In any event, with declining downtown office development it became increasingly obvious from the late 1980s that future office markets would be too limited to support intended development.

From the mid-1980s onwards, pressure for a change in the organizational set-up of the Toronto waterfront gained momentum. Harbourfront, originally introduced as a park and having evolved into the site of increasingly dense development, became the main flashpoint in the opposition to prevailing waterfront institutional arrangements and resulting land use patterns. In 1987, under the impetus of the City of Toronto, its former planning commissioner, Stephen McLaughlin, prepared a report on federal properties on the waterfront (McLaughlin 1987). Lamenting the fragmentation of those properties among many agencies and the absence of coordination between them, it recommended a joint federal/provincial review of waterfront development. McLaughlin’s proposal led to the launching by these two levels of government of the Royal Commission on the Future of the Toronto Waterfront, placed under the direction of David Crombie, a former City of Toronto mayor. Crombie supported McLaughlin’s view that the province should be involved in the royal commission. After all, the province had long been a vocal critique of the federal approach to waterfront redevelopment.

The royal commission was highly critical of prevailing development patterns. It recommended the separation of land use development from the other objectives pursued by the agencies (RCFTW 1989b). Above all, it adopted a strong environmental stance, adhering to a watershed perspective including not only the Lake Ontario waterfront but also the rivers and creeks flowing into the lake. Such a stance thus called for a coordinated approach to planning, in stark opposition with the fragmented development that had characterized the waterfront. In this regard, the commission recommended setting up the waterfront Regeneration Trust, mandated to coordinate waterfront redevelopment and advise the province on waterfront issues (RCFTW 1992). Planning models were also evolving. By the late 1980s, the popularity of grand modernist schemes, such as those put forth by the Metro Centre plan, had made way for more traditional forms of development characterized by their medium-density, grid patterns and pedestrian-hospitable retail streets. The redeveloped St Lawrence neighbourhood, immediately to the north of the waterfront, came to epitomize this form of development.

Attempts at Coordination: From the 1990s Onwards

Institutional changes began to unravel in the wake of the royal commission report entitled Regeneration. Following the advice of David Crombie, city councillors used their majority on the THC board to transfer most of its land to the City of Toronto Economic Development Corporation (TEDCO), a municipal agency set up to generate employment and economic development on underused industrial land (Tasse 2006, 15). Other THC board members, including some city councillors, contested the legality of this transfer, but to no avail. Meanwhile, the Canada Lands Company, a Crown corporation responsible for divesting surplus federal property, sold CN railway lands to a large residential developer (Toronto Star, 26 March 1997). So by the mid-1990s the federal government presence on the waterfront was much diminished.

But the federal government wanted to remain an important player on the waterfront for visibility, patronage, and electoral reasons. Toronto Liberal members of parliament were successful in having the Toronto port classified among those worthy of federal attention, even though its regional rather than national scale clearly demarcated it from other ports thus classified (Canada 1996; Toronto Star, 29 March 1996). From 1999, the Toronto port was administered by the newly formed Toronto Port Authority (TPA), an arm’s length federal agency. The TPA was differentiated from the THC by the composition of its board, no longer composed of a majority of City of Toronto appointees, and its limited land holdings: the port, the outer marina, and the Island Airport (renamed City Centre Airport in 1994) (Tasse 2006, 30). The board was largely composed of federal government patronage appointments.

Government interest in the Toronto waterfront crested between 1999 and 2001 when Toronto prepared its bid for the 2008 Olympic Games. Most of the attention focussed on the eastern portion of the waterfront, which was to be the site of the main Olympic installations, including the Olympic village, but redevelopment efforts were also targeted at the entire waterfront. In 2001, the three levels of government created the Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation (TWRC), mandated for the redevelopment of the forty-six kilometres of the amalgamated City of Toronto waterfront. The agency, which was promised $1.5 billion by the three levels of government, was meant to showcase the Toronto capacity to hold the Olympic Games (Toronto Star, 1 March 2001; 2 March 2001).

The waterfront redevelopment strategy was slow to take off after the failure of the Olympic bid. By early 2004, only $35 million in government funds had been transferred to the TWRC (Toronto Star, 9 May 2002, 4 March 2004, 5 March 2004). Later that year, however, the federal and provincial governments allocated $334 million for different projects, including naturalization of the mouth of the Don River, remediation of industrial sites in the Port Lands to make them suitable for housing and parks, and a boardwalk along Harbourfront Centre. Of late, under the coordinating eye of the TWRC, relabelled Waterfront Toronto, the province, the City of Toronto and the federal government each concentrates on a different portion of the waterfront. The province is proceeding with the development of the West Don Lands, a future neighbourhood of six thousand new residential units and ancillary retailing and services, and the city is engaged in the creation of the East Bayfront neighbourhood, which will contain six thousand new residences and eight thousand jobs, along with 5.5 hectares of parks and open space (Globe and Mail, 6 May 2005; Toronto Star, 27 March 2006) (see figure 6.1). For its part, the federal government is providing new parks (Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation 2005; interview with president and CEO of Waterfront Toronto).

The filling in of the Toronto waterfront is also taking place on the railway lands (see figure 6.1). In the early 2000s, Grand Adex Properties (renamed Concord Adex) began the construction of residential condominium towers modelled in part on the company’s residential redevelopment of the Vancouver Expo 86 site, widely praised in planning and architectural circles (Globe and Mail, 10 July 1997; 24 September 1997; Punter 2003). At built out, City Place (the name given to the Concord Adex project) will consist of seventeen residential towers along with a number of lower structures. The railway lands are also experiencing the development of other condo buildings and two new office towers.

Recent redevelopment of the waterfront did not take place without jarring episodes. Despite its status as an agency of the city, TEDCO pursued its short term economic development objectives with little consideration for the city’s planning goals for the waterfront. As the city was engaged in the preparation of the Olympic bid, TEDCO signed a twenty-year lease with a food retailer for a three-hectare property across the street from the proposed Olympic stadium. In a similar vein, TEDCO’s proposal for an entertainment studio on the East Bayfront clashed with the land use plans adopted by Waterfront Toronto (Toronto Star, 25 March 2000; 27 March 2000a; 27 March 2000b; 17 April 2000; 7 October 2004). TEDCO also resisted a City of Toronto request to transfer some of its land to the TWRC. The city had to take the extreme measure of using a shareholder declaration – the city being the sole shareholder – to force TEDCO to divest itself of its land. In 2008 the City of Toronto replaced TEDCO with two new agencies (Toronto Star, 30 September 2008).

The expansion of the City Centre Airport had long been a source of conflicts opposing the THC, which was eager to increase revenues from the airport, to nearby residents (Community AIR 2007; Globe and Mail, 26 November 2002; National Post, 29 November 2002). Opponents were successful in securing and maintaining a ban on commercial jets. The City Centre Airport again became an object of contention when the TPA received City of Toronto support for the construction of a bridge to the airport, which would replace an inconvenient ferry service. For the opponents of the bridge, the proposal would inevitably lead to an expansion of the airport. They argued that the waterfront could not accommodate in close proximity high-density residential development and a busy airport and that increased air traffic would compromise the future of the waterfront. The controversy over the bridge became the main issue of the 2003 municipal election. Toronto Councillor David Miller, who alone among mayoralty candidates opposed the bridge, won the race (Toronto Star, 14 October 2003). After his victory, Miller helped cancel the bridge and convinced the federal government to assume ensuing liability toward the TPA and the operator of the airport (Globe and Mail, 13 May 2004; 4 May 2005; Toronto Star, 4 May 2005) (For a synopsis of the Toronto waterfront redevelopment issues see table 6.1).

INSTITUTIONAL INTERPRETATIONS

In this section we explain different aspects of the narrative from an institutional perspective. We consider features of the institutional makeup, dynamics stemming from relationships between institutions, and effects on Toronto waterfront land use.

The first question concerns the presence of so many agencies on the waterfront. Three conditions were associated with the creation of these agencies. First, agencies were set up to deal with specific issues, as noted in the case of the creation of the THC being given responsibility for port operation and expansion in the early twentieth century and the creation of the Harbourfront Corporation in the 1980s to oversee the development of the central part of the waterfront and to set up cultural programming. These two examples illustrate the concurrent existence of one long-lasting organization responsible for enduring functions and of another created to carry out a mandate that proved to be short-lived in comparison. We have also seen that in other circumstances agencies can become mired in controversy when not suited to emerging circumstances and be disbanded and replaced by other agencies. This was the fate of the THC, whose responsibilities were ultimately taken over by TEDCO and the TPA. A final factor relates to the involvement of different levels of government, mainly the federal government and the City of Toronto, but also the province, and their need to set up agencies to deal with waterfront-related matters. Such a requirement was especially felt by the federal government, which relied on arm’slength agencies to ensure input from local stakeholders and develop expertise on different aspects of the waterfront. More recently, the City of Toronto also relied on agencies – TEDCO and TWRC/Water-front Toronto. All these factors account for the complex institutional scene on the Toronto waterfront.

Table 6.1

Major Inter-agency Tensions in the Redevelopment of the Toronto Waterfront

The behaviour of individuals operating within agencies generally coincides with the interests of these agencies. Organizations indeed rely on systems of incentives and penalties to ensure consistency between their objectives and the behaviour of their members (Pierson 2000). In the most successful instances, individuals identify their interests with those of the agency they belong to. The resulting consistency in the behaviour of individuals operating within their institutional structure warrants the perception of agencies as actors in their own right. Uncomfortable situations have arisen when the same individuals have belonged to two organizations in a conflicting situation. Board members have had fiduciary responsibility for the organizations to which they belonged, forcing them to change their positions as they moved between organizations. The narrative has documented such an instance involving City of Toronto councillors who were also members of the THC board. In the words of a former chief planner for the City of Toronto: “I always found it interesting that, when councillors were appointed to the former Harbour Commission, they could have a speech at Council, and as soon as they were sitting at the Harbour Commission’s table, they were different persons. And they would argue against what they said at Council. You know, it was like a private club.”

Dissimilarities in the positions taken by different agencies and resulting conflicts can be attributed to their respective mandates and institutional structures, which determined the nature of their relations with their societal environment as well as between each other. While the THC, Harbourfront, TEDCO, and the TPA were largely shielded from electoral pressures and could thus pursue their respective financial sustainability objectives with little concern for public opinion, when they intervened on the waterfront, governments had to heed public sentiments. However, sensitivity to local pressures varied according to the level of government. As expected, this sensitivity was much higher for the City of Toronto than for senior governments, for whom the waterfront issues affected but a small share of their overall electorate and played a minor role within their wide range of responsibilities.

The self-interest of organizations drove their perception of waterfront-related issues and of possible responses. Different organizational self-interests therefore translated into different perceptions of problems and solutions, which explain a profusion of discourses on the waterfront. Over much of the history of the Toronto waterfront redevelopment, agencies operated as fiefdoms with considerable control over portions of the waterfront under their jurisdiction. Without the capacity to impose its planning vision on most waterfront agencies, attempts by the City of Toronto to plan the entire waterfront simply added to the number of perspectives on the waterfront. In a context of fragmented jurisdictions and power, there was no available mechanism to determine the superiority of one perspective over another. The result was relativism in views on the waterfront. The discourse of each organization focused on its own slice of reality. For example, at the same time that the City of Toronto was promoting a vision of the waterfront that emphasized residential development and recreational space, the TPA stressed the importance of the port function and of the City Centre Airport. As stated by a TPA executive: “You know even Waterfront Toronto brings in great planners and visionaries. They look at what we have waterwise and airport-wise and they say: You are so lucky. Because they get it, they get transportation and transportation has always been the afterthought relative to design and it bothers the hell out of me because regarding transportation, you set your links first and design around it.”

Decision-making dynamics on the waterfront mirrored the complicated agency makeup. Projects had to be consistent with the capacities of the agencies and their self-interest. For example, the ambitious planning visions of the 1960s were incompatible with the resources available to the THC, as well as with its mandate. Rather than pursuing such grand visions, the THC engaged in piecemeal development to generate the revenues it required to operate the port. The presence of different agencies was also responsible for a fragmented development pattern. Each agency developed land according to its own priorities, which explains profound differences in the configuration of different portions of the waterfront: the THC lands, Harbourfront, and the Railway Lands. Planning objectives often took a distant second place to the more immediate financial self-sustainability objectives of agencies. What is more, efforts at coordinating development inevitably became enmeshed in interagency conflicts, a cause of prolonged delays (Gordon 1997). The protracted and fragmented nature of waterfront redevelopment in Toronto, along with its focus on high-density redevelopment, can be contrasted with the Chicago experience. There, the redevelopment of the central portion of the waterfront resulted in a series of large parks with design features worthy of their prestigious location. Two factors accounting for the difference between the two experiences are the role played by the City of Chicago at key stages of the redevelopment and the existence of a strong mayoral system, which made for commanding leadership throughout the process (Green and Holli 2005; Holli and Green 1999).

We must remain aware that the institutional perspective offers but one, albeit an important, layer of explanation for the form Toronto waterfront redevelopment took. Major societal tendencies, such as the economic transition to post-industrialism and the shift to post-modern values leading to the passage from a functional approach to the city to one that emphasizes quality of life, have also played a key role (Bell 1999; Kumar 1995). But the narrative has shown that the impact of these tendencies on the waterfront was largely filtered by its inter-agency dynamic. It is also important to consider the part individuals played in the redevelopment process. If in most cases the actions of individuals contributed to the perpetuation of existing agencies, as implied by the path dependency perspective, in exceptional circumstances influential individuals were instrumental in the transformation of the institutional scene. Perhaps most important was the impact of David Crombie. As chair of the Royal Commission on the Future of the Toronto Waterfront and as a respected former politician, David Crombie played a central role in the dismantling of the THC and the adoption of a coordinated approach to waterfront redevelopment.

There is, finally, the impact of social forces on the waterfront. The narrative has pointed to the role at different times of the Board of Trade and business interests, developers, political parties and caucuses (at the municipal level), public opinion, and neighbourhood organizations. For example, we have seen that the creation of the THC resulted from lobbying on the part of the Board of Trade, that in the case of Harbour Square and much of the Railway Lands the full redevelopment concepts originated from developers, and that changes in political parties and caucuses in power translated at the federal level into a loss in subsidized housing funding and at the municipal level into shifts from pro-development to pro-planning-control attitudes. Moreover, neighbourhood movements manifested themselves by preventing a change in the Island Airport location and by later pressing for limits in its expansion, and public opinion voiced its opposition to the density of Harbourfront development. Despite the insensitivity to social forces of agencies with appointed boards (notwithstanding those forces that are essential to the pursuit of their objectives), these forces nonetheless had a considerable impact on the waterfront institutional configuration. At different junctures they indeed had the capacity to influence levels of government, which in turn modified the agency landscape in response to issues raised by social forces. Most notably, reacting to public opinion that was increasingly hostile to the trajectory of waterfront redevelopment, the federal and provincial governments launched the Royal Commission on the Toronto Waterfront, leading to the subsequent agency re-jigging. Our contention remains, however, that the institutional set-up was the main factor driving waterfront redevelopment. Social forces may have contributed to the institutional configuration, but ultimately it was institutionally based factors, such as tension between levels of government, the pursuit by organizations of their respective self-interests, and inter-organizational rivalry that were determinant. It was through these institutional dynamics that the impact of social forces was felt.

The history of the Toronto waterfront over the last hundred years was divided into three phases. The first was dominated by the THC and focused on the port and industrial functions of the waterfront. The second phase witnessed a proliferation of post-industrial visions for the waterfront and some post-industrial redevelopment, but little connection between the two. The scale, the configuration, and the sequence of the developments that took place over the period did not match the visions. The period also experienced the setting up of different agencies responsible for the development of distinct parts of the waterfront. Finally, the third phase has been characterized by attempts to move away from the institutional and land use fragmentation that has defined the previous period, leading to the setting up of an overarching agency. But the narrative has shown that although this institutional reconfiguration was favourable to coordinated development, it did not rule out inter-agency and land use conflicts.

As a rule, institutional structures play a critical role in the formulation of policies and in determining policy outcomes. They are not just one among different sources of influence: they are mediators, filtering the effects of other factors. They shape how economic, social, and political tendencies are reflected in land use outcomes. What distinguishes most the Toronto waterfront is its exceptionally complex institutional structure. Likely more than elsewhere, planning outcomes on the Toronto waterfront have therefore been determined by inter-agency dynamics, possibly at the expense of other sources of influence on land use development and planning.

Development on the waterfront, characterized by fragmented land use patterns, high-density configurations with relatively little public space, and the presence of conflicting uses in close proximity to each other, mirrors the presence of multiple agencies, each driven by its own self-interest. What if the Toronto waterfront had been placed under the mandate of a single agency from the outset of the redevelopment process? We can assume that land development would have been less fragmented, that more public space would have been provided and different developments would have been better integrated, thus ruling out conflicting situations such as the one noted in the case of the City Centre Airport and surrounding residential areas. Also, depending on financial arrangements within this agency, the outcome may have been lower development density and additional public space. But it would have been important for this agency to have a strong planning vision; otherwise we could have witnessed haphazard redevelopment even under the mandate of a single agency, as happened when the THC dominated the waterfront.

REFERENCES

Bacher, John C. 1993. Keeping to the Marketplace: The Evolution of Canadian Housing Policy. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Bell, Daniel. 1999. The Coming of Post-industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting. New York: Basic Books.

Booz-Allen and Hamilton. 1992. Organizational Plan and Budgets for the Toronto Harbour Commission: Final Report. Toronto: Toronto Harbour Commissioners and Toronto Economic Development Corporation.

Burchell, Robert W., and David Listokin. 1978. The Fiscal Impact Handbook: Projecting the Local Costs and Revenues Related to Growth. New Brunswick, NJ: Center for Urban Policy Research.

Canada. 1911. Statutes, Act 1–2 George V, Chapter 26. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

– 1996. Bill C–44, The Canada Marine Act. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

Castells, Manuel. 1983. The City and the Grassroots: A Cross-cultural Theory of Urban Social Movements. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Clingermayer, James C., and Richard C. Feiock. 2001. Institutional Constraints and Policy Choices: An Exploration of Local Governance. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Community AIR. 2007. Accessed January 2008, http://communityair.org/.

Community Development Consultants Ltd. 1968. Metro Centre: Technical Report. A Study for the Development of Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Railway Lands in Central Toronto. Toronto: Community Development Consultants Ltd.

Deephouse, David L., and Mark Suchman. 2008. “Legitimacy in Organizational Institutionalism.” In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, edited by Royston Geenwood, Christine Oliver, Kerstin Sahlin and Roy Suddaby, 49–77. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Desfor, Gene. 1993. “Restructuring the Toronto Harbour Commission: Land Politics on the Toronto Waterfront.” Journal of Transport Geography 1: 167–81.

Desfor, Gene, Michael Goldrick, and Roy Merrens. 1989. “A Political Economy of the Waterfrontier: Planning and Development in Toronto.” Geoforum 20 (4): 487–501.

DiMaggio, Paul J. 1988. “Interest and Agency in Institutional Theory.” In Institutional Patterns and Organizations: Culture and Environment, edited by Lynne G. Zucker, 3–21. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

Downs, Anthony. 1967. Inside Bureaucracy. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

Epstein, David, and Sharyn O’Halloran. 1999. Delegating Powers: A Transaction Cost Politics Approach to Policy Making under Separate Powers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fainstein, Susan S. 2000. “New Directions in Planning Theory.” Urban Affairs Review 35:451–78.

Forester, John. 1989. Planning in the Face of Power. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The Constitution of Society. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Globe and Mail. 1963. “Board of Control Approves Waterfront Plan,” 27 July, 23.

– 1965. “City, Developer Sign Deal on Waterfront,” 4 September, 26.

– 1976. “Harbourfront Is Not Dead – It’s Just Sleeping,” 25 May, 1–2. (G. Fraser).

– 1979. “Harbourfront Gets Pledge of Financing,” 31 March, 15.

– 1980. “Harborfront Plan Placates Opponents,” 14 June, 5.

– 1980. “Toronto Lays Groundwork for Waterfront Community,” 24 June.

– 1986. “City, Harbourfront Agree on Plan for Limited Waterfront Development,” 8 April, A15. (Z. Kashmeri).

– 1986. “Harbourfront Apartments Approved over Accusations of Rushing Project,” 23 April, A13. (M. Gooderman).

– 1986. “Taxpayers May Be the Losers in Land Sale, Councillors Fear,” 30 August 2, 30. (S. Fine).

– 1986. “Council Approves $400 Million Waterfront Development,” 2 December, A20. (P. Taylor).

– 1987. “Direction of Harbourfront Assailed by Residents,” 18 March, A13. (P. Taylor).

– 1997. “Terry Hui’s Real Estate Star Poised to Rise to New Level,” 10 July B1. (A. Gibbon).

– 1997. “Grand Design for Toronto’s Railway Lands Faces Hearing; Vancouver Developer’s $1 Billion Plan Would Revamp City’s Skyline,” 24 September, B6. (L. Zehr).

– 2002. “Crombie, Jacobs Attack Airport Plan,” 26 November, A21. (J. Rusk).

– 2004. “Mayor Urges Ottawa to Sign Deal Killing Bridge,” 13 May, A13. (K. Harding).

– 2005. “Ottawa Pays $35 Million to Abort Bridge,” 4 May, A1. (J. Lewington).

– 2005. “West Don Lands Get the Nod,” 6 May, A15. (J. Lewington).

Gordon, David L.A. 1994. Implementing Urban Waterfront Redevelopment. PhD diss., Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

– 1997. “Managing the Changing Political Environment in Urban Waterfront Redevelopment.” Urban Studies 34, 61–83.

Greenberg, Ken. 1996. “Toronto: The Urban Waterfront as a Terrain of Availability.” In City, Capital and Water, edited by P. Malone. London: Routledge.

Green, Paul M., and Melvin Holli, eds. 2005. The Mayors: The Chicago Political Tradition. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. Greenwood, Royston, Christine Oliver, Kerstin Sahlin, and Roy Suddaby. 2008. “Introduction.” In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, edited by Royston Geenwood, Christine Oliver, Kerstin Sahlin, and Roy Suddaby, 1–46. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Hall, Peter A., and Rosemary C.R. Taylor. 1996. “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms.” Political Studies 44: 936–57.

Hamel, Pierre, Henri Lustiger-Thaler, and Margit Mayer. 2000. Urban Movements in a Globalizing World. London: Routledge.

Harbourfront Corporation. 1978. Harbourfront Development Framework. Toronto: Harbourfront Corporation.

Hartmann, Franz. 1999. “Nature in the City: Urban Ecological Politics in Toronto.” PhD diss., York University, Toronto.

Healey, Patsy. 1999. “Institutional Analysis, Communicative Planning, and Shaping Places.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 19:111–21.

Hodge, Gerald. 1972. “The Care and Feeding of an Airport, or the Technocrat as Midwife.” In The City: Attacking Modern Myths, edited by A. Powell. Toronto: McLelland & Stewart.

Holli, Melvin G., and Paul M. Green. 1999. A View from Chicago’s City Hall: Mid-century to Millenium. Charleston, SC: Arcadia.

Horn, Murray. 1995. The Political Economy of Public Administration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ircha, Michael C. 1993. “Institutional Structure of Canadian Ports.” Maritime Policy and Management 20:51–66.

Jones, Bryan D. 2001. Politics and the Architecture of Choice. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Krasner, Stephen. 1984. “Approaches to the State: Alternative Conceptions and Historical Dynamics.” Comparative Politics 16: 223–46.

Kumar, Krishan. 1995. From Post-industrialism to Post-modern Society: New Theories for the Contemporary World. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lauria, Mickey, ed. 1996. Reconstructing Urban Regime Theory: Regulating Urban Politics in a Global Economy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lemon, Jim. 1990. The Toronto Harbour Plan of 1912: Manufacturing Goals and Economic Realities. Toronto: Canadian Waterfront Resource Centre.

Magnusson, Warren. 1996. The Search for Political Space: Globalization, Social Movements, and the Urban Political Experience. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

March, James G., and Johan P. Olsen. 1996. “Institutional Perspective on Political Institutions.” Governance: An International Journal of Policy and Administration 9:247–64.

McCabe, Barbara C., and Richard C. Feiock. 2005. “Nested Levels of Institutions: State Rules and City Property Taxes.” Urban Affairs Review 40: 634–54.

McLaughlin, David J. 1992. “The Planning and Development of Harbourfront: An Historical Analysis.” Master’s thesis, York University, Toronto.

McLaughlin, Stephen. 1987. Federal Land Management in the Toronto Region. Toronto: Stephen G. McLaughlin Consultants.

Mellen, Frances Nordlinger. 1974. “The Development of the Toronto Waterfront during the Railway Era, 1850–1912.” PhD diss., University of Toronto.

Merrens, Roy. 1988. “Port Authorities as Urban Land Developers: The Case of the Toronto Harbour Commissioners and their Outer Harbour Project, 1912–68.” Urban History Review 17:92–105.

Metropolitan Toronto Planning Board. 1967. The Waterfront Plan for the Metropolitan Toronto Planning Area. Toronto: Metropolitan Toronto Planning Board.

– 1970. Metro Centre: A Review of the Proposed Development on the Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Railway Lands in Downtown Toronto. Toronto: Metropolitan Toronto Planning Board.

Miron, John R., ed. 1993. House, Home and Community: Progress in Housing Canadians, 1945–1986. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

National Post. 2002. “Councillors Have Killed Waterfront: Airport Expansion, Bridge Approved despite Concerns,” 29 November, A17. (D. Wanagas).

Orr, Marion, and Valerie C. Johnson. 2008. Power in the City: Clarence Stone and Politics of Inequality. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

Peters, B. Guy. 1996. “Political Institutions, Old and New.” In A New Handbook of Political Science, edited by Robert E. Goodin and Hans-Dieter Klingermann. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

– 2005. Institutional Theory in Political Science: The “New Institutionalism. 2d ed. London: Continuum.

– 2008. “Institutional Theory: Problems and Prospects.” In Debating Institutionalism, edited by Jon Pierre, B. Guy Peters, and Gerry Stoker, 1–21. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Peterson, Paul E. 1981. City Limits. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Pierre, Jon, B. Guy Peters, and Desmond S. King. 2005. “The Politics of Path Dependency: Political Conflict in Historical Institutionalism.” Journal of Politics 67: 1275–1300.

Pierson, Paul. 2000. “The Limit of Design: Explaining Institutional Origins and Change.” Governance: An International Journal of Policy and Administration 13: 475–99.

Pierson, Paul, and Theda Skocpol. 2002. “Historical Institutionalism in Contemporary Political Science.” In Political Science: State of the Discipline, edited by Ira Katznelson and Helen V. Milner. New York, NY: Norton.

Powell, Walter W., and Paul DiMaggio, eds. 1991. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Punter, John. 2003. The Vancouver Achievement: Urban Planning and Design. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Ramlalsingh, Roderick D. 1975. A Study of the Decline of Trade at the Port of Toronto. Toronto: York University Department of Geography Discussion Paper Series.

Royal Commission on the Future of the Toronto Waterfront (RCFTW). 1989a. Persistence and Change: Waterfront Issues and the Board of Toronto Harbour Commissioners. Toronto: Royal Commission on the Future of the Toronto Waterfront.

– 1989b. Interim Report: Summer, 1989. Toronto: Royal Commission on the Future of the Toronto Waterfront.

– 1990. Watershed. Toronto: Royal Commission on the Future of the Toronto Waterfront.

– 1992. Regeneration: Toronto’s Waterfront and the Sustainable City: Final Report. Toronto: Queen’s Printer of Ontario.

Schaeffer, Roy. 1974. The Board of Trade and the Origins of the Toronto Harbour Commissioners, 1899–1911. Toronto: York University Department of Geography Discussion Paper Series.

Scott, W. Richard. 1995. Institutions and Organizations. 2d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sewell, William H. Jr. 1992. “A Theory of Structure: Duality, Agency, and Transformation.” American Journal of Sociology 98:1–29.

Skocpol, Theda. 1992. Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Steinmo, Sven, Kathleen Thelen, and Frank Longstreth. 1992. Structure Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tasse, Roger. 2006. Review of Toronto Port Authority Report. Toronto: Gowling Lafleur Henderson LLP Barristers & Solicitors.

Thornton, Patricia H., and William Ocasio. 2008. “Institutional Logics.” In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, edited by Royston Geenwood, Christine Oliver, Kerstin Sahlin, and Roy Suddaby, 99–129. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Toronto City Council. 1982. Agreement between Harbourfront Corporation and the Corporation of the City of Toronto. Toronto: Toronto City Council.

Toronto Harbour Commission. 1968. A Bold Concept for the Redevelopment of the Toronto Waterfront. Toronto: Toronto Harbour Commission.

Toronto Harbour Commissioners. 1912. Toronto Waterfront Development, 1912–1920. Toronto: Toronto Harbour Commissioners.

Toronto Planning Board. 1962. The Core of the Central Waterfront: A Proposal by the City of Toronto Planning Board. Toronto: Toronto Planning Board.

– 1974. The Central Waterfront: Proposal for Planning. Toronto: City of Toronto Planning Board.

Toronto Planning Department. 1980. Harbourfront Part 2 Official Plan (Office Consolidation). Toronto: Toronto Planning Department.

Toronto Star. 1969. “Only Luxury Apartments Feasible in Harbour Study,” 10 April, 39. (D. Dutton).

– 1977. “Waterfront Plan a World of Its Own,” 24 March, C04. (M. Best).

– 1979. “Shops and Housing – That’s the Plan for Harbourfront,” 9 February, A03. (D. Miller).

– 1979. “Liberals’ Fall Leaves Harbourfront in Limbo,” 7 October, A03. (J. Dineen).

– 1980. “Ottawa Gives Harbourfront $25 Million,” 13 June, A01. (P. Rickwood and H. Mietkiewicz).

– 1986. “$24 Million Sale of Harbour Land Called Too Low,” 28 August, A6. (T. Kerr).

– 1986. “Harbour Commission Refuses Demand for Land Sale Details, 29 August, A6. (T. Kerr).

– 1987. “Parks Commissioner vs. Harbourfront,” 2 January, A19. (D.L. Stein).

– 1996. “City Balks at Ottawa’s Port Plan – Won’t Give Up Control to Business Board,” 29 March, E3. (P. Moloney).

– 1997. “$2 Billion Plan Will Transform Railway Land,” 26 March, A1. (T. Wong).

– 2000. “Mystery As Tycoon Steve Stavro Wins New 20-Year Lease,” 25 March, NE01. (J. Lakey and B. Spremo).

– 2000a. “Waterfront Chief Warned Against Deals – Port-land Officials Went Ahead with 20-Year Lease,” 27 March, B1. (J. Lakey).

– 2000b. “Land ‘Scandal’ Spoils Task Force’s Big Day,” 27 March, GT01. (R. James).

– 2000. “TEDCO Fumble Could Trip Up Fung’s Plan,” 17 April, GT01. (R. James).

– 2001. “Superagency to Redevelop Waterfront – Three Governments Kick In $300 Million to Start Key Projects,” 1 March, GT01. (J. Lakey).

– 2001. “Waterfront Agency Raises Concerns – Accountability of Unelected Board Questioned,” 2 March, GT01. (M. Welsh and J. Lakey).

– 2002. “Waterfront Corporation Still Adrift with No Power,” 9 May, D03. (C. Hume).

– 2003. “Bridge over Troubled Waters,” 14 October, A23. (T. Walkom).

– 2004. “Fung Weary of Playing Waterfront Games: Corporation Head Upset about Slow Pace of Development; Lack of Funds, Bureaucracy Described as Major Hurdles,” 4 March, B04. (K. Gillespie).

– 2004. “Waterfront Corporation Starved for Cash, May Fold; Said to Be 26 Days from Shutdown; Projects Delayed; Ottawa Owes $10M,” 5 March, B01. (K. Gillespie).

– 2004. “Going Madly Off in All Directions,” 7 October, B02. (C. Hume).

– 2005. “Bridge Battle Finally Over,” 4 May B01. (H. Safieddine and R. James).

– 2006. “From ‘Wasted’ to ‘People’ Place: West Don Lands Development Just Makes Sense, Caplan Says,” 27 March, A01. (K. Gillespie).

– 2008. “City to Replace TEDCO: Two New Agencies – One to Develop, the Other a Marketing Body – Will Fulfill Firm’s Role,” 30 September, 30. (J. Spears).

Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation. 2005. Commissioners Park. Toronto: TWRC.

Weaver, R. Kent, and Bert A. Rockman. 1993. Do Institutions Matter? Government Capabilities in the United States and Abroad. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Weingast, Barry R. 2002. “Rational Choice Institutionalism.” In Political Science: State of the Discipline, edited by I. Katenelson and H.V. Milner. New York, NY: Norton.

Wildavski, Aaron. 1987. “Choosing Preferences by Constructing Institutions: A Cultural Theory of Preference Formation.” American Political Science Review 81: 3–22.

Wolfe, Jeanne M. 2003. “A National Urban Policy for Canada? Prospects and Challenges.” Canadian Journal of Urban Research 12: 1–21.