Tracking the Growth of the Federal Municipal Infrastructure Program under Different Political Regimes

INTRODUCTION

Since the mid-1990s, the Federal Municipal Infrastructure Program has become a milestone in the history of relations between federal, provincial, and municipal governments – thus called “multilevel governance.” This program was born in the context of a debate on the deficit of municipal infrastructure1 in Canada, and the goal was to stimulate investments in infrastructure in Canadian municipalities.

Since the creation of the program in 1994, important political changes have taken place in Ottawa. The Liberal political regime, led successively by Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin (1994–2006), oversaw the creation and the development of the program. Later, in 2006, the Liberal Party was defeated and replaced by a new conservative regime. Between 2006 and 2010 successive conservative governments led by Prime Minister Stephen Harper were able to hold power through minority governments.2 One could have expected that the Conservative government would initiate a series of reforms promoting a “low-fat diet” infrastructure spending policy and less intrusive government in Canada. If it had, the municipal infrastructure program, which involves a significant federal public expenditure of several billion dollars, would have been subject to severe cutback. But the expected reforms did not happen. In fact, the Conservative Party has not only extended this investment program but also increased its budget substantially before and after the economic crisis of 2008–10. In this chapter, I try to understand and explain the sustained political support for this program through the political regimes that have succeeded.

Despite political changes, Bojorquez, Champagne, and Vaillancourt (2009) have observed that the general nature of the municipal infrastructure program remained relatively stable over time. Despite some differences, most of the municipal federal infrastructure funds are “conditional grants” with tripartite cost-sharing. These funds rely on intergovernmental arrangements rather than on unconditional block grants, which could have provided more autonomy to municipalities without matching funds.

This research poses the question, what explains the rise of multilevel governance between the federal government and Canadian municipalities across party lines? I use the case of infrastructure investments in Canada to argue that municipalities have become key players in intergovernmental relations in Canada. I also maintain that this renewed federal-municipal relationship is contributing to gradually changing conventional Canadian federalism based on federal-provincial arrangements.

I use as a theoretical framework the model of Andrew, Graham, and Phillips (2002) to describe the changing context for urban and municipal policies in Canada. First, the current internationalization process gives Canadian cities a new economic and social role in the world economy. Second, the immigration boom and demographic growth in Canada occur mainly in large Canadian centres. Finally, the increased pressure on municipal governments resulting from the off-loading of provincial responsibilities within their jurisdiction calls for a keener recognition of those governments. Bradford (2004, 43) asserts that “new thinking is needed that respects provincial constitutional responsibility for municipal governments while also fully recognizing that metropolitan issues, from the environment and housing to employment and immigration, transcend the jurisdictional compartments.”

As Berdahl (2004) points out, the role of municipalities has been an important matter of Canadian concern since the late 1990s, when a transformation in the existing federal-municipal relations became inevitable. The absence of formal constitutional constraint in various urban issues made federal commitment in municipal affairs relentless. On a purely constitutional basis, through its spending power the federal government is free to spend its financial resources, or lend them to any government or institution it chooses, for any purpose (Sancton and Young 2003). What the federal government cannot do is to create laws or policies in relation to municipalities, since municipal institutions are ruled by provincial powers. Thus, it can be argued that the provinces could have challenged the Federal Municipal Infrastructure Program more intensively if they had been in better financial health. But we now see that through that program a new federal-municipal relationship is emerging around tripartite political and bureaucratic interactions and agreements between the federal and provincial governments and the municipalities.

More recently, Stoney and Graham (2009, 391) have depicted the latest generation of federal-municipal machinery as “a tendency to buy rather than build federal influence, the move from a unilateral, centralized federal approach to a more decentralized intergovernmental approach, the shift from social policies to investment in physical infrastructure, and some tenuous signs of a trend towards longer-term funding through programs like the Gas Tax Fund and the Building Canada initiative.” From the same perspective, a substantial body of literature, which includes studies by Kitchen (2002), Slack (2002), McMillan (2006), and Bojorquez, Champagne, and Vaillancourt (2009), also explores municipal finances as a key driver of a renewed intergovernmental fiscal relations framework in Canada. In particular, it suggests that economic and social problems are changing and that the division of responsibilities for public services and expenditures among each level of government has an important impact on Canadian federalism and most especially on how the federal government interacts with the municipalities.

Intergovernmental relations, mainly between the provinces, the territories, and the federal government, shape Canada’s traditional political organization. Municipalities have been delegated authority by the provinces to perform certain duties. Provincial rules and regulations thus govern municipalities, which are eventually constrained by jurisdiction and by the resulting limited powers delegated to them by the provincial rules and regulations (McAllister 2004). However, since the mid-1990s, the federal government has shown an increasing interest in urban and municipal issues. To some extent, the role of municipalities has become an important matter of national Canadian concern. A transformation in existing federal-municipal relations evolved particularly through the municipal infrastructure program. In this paper, I first describe the birth of the federal government’s municipal infrastructure program from 1994 to 2002 and then look at the evolution of the program from 2002 to 2010, a period of continuous political turbulence. I focus on four periods:

1 The first Liberal period, from 2002 to 2004, the end of Prime Minister Chrétien’s regime, is characterized by the creation of Infrastructure Canada, a new department intended to deal with cities.

2 The second Liberal period, from 2004 to 2006, is typified by Prime Minister Paul Martin’s New Deal for Cities.

3 The first Conservative period since the election of the Conservative Party headed by Prime Minister Stephen Harper in 2006 runs from 2006 to 2008 and is characterized by the expansion of the New Deal for Cities and the introduction of a Public-Private Partnership program for infrastructure investments.

4 The second Conservative period, from 2008 to 2010, is marked by Canada’s Economic Action Plan to deal with the global economic crisis and the implementation of the Infrastructure Stimulus Fund.

I then move on to discuss some conclusions regarding the growth of the Federal Municipal Infrastructure Program, along with the rise of multilevel governance between the federal government and Canadian municipalities across party lines.

THE BIRTH OF THE FEDERAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM, 1994–2002

When Liberal prime minister Jean Chrétien won the 1993 election, municipal and urban issues were a strong component of his electoral platform (Liberal Party of Canada 1993). The federal government rapidly implemented a series of programs that were oriented toward the creation of opportunities for increased funding in municipal infrastructure through the Canada Infrastructure Works Program, created in 1994. Before Chrétien’s election, the federal government had, for a period of almost fifteen years, almost completely overlooked the needs of municipal governments in Canada. Yet, in the 1960s and 1970s, the federal government had implemented several programs targeted at municipalities, such as the Sewer Treatment Program, which provided $979 million in loans and $131 million in grants to local governments from 1961 to 1974 (Hilton 2007). In 1970 the federal government created the Ministry of State for Urban Affairs (MSUA) to develop cooperative relationships on urban issues among the federal government, the provinces, and the municipalities. Although from 1975 to 1978, the MSUA managed a federal infrastructure program to address the financial troubles of local governments, it had a short life span (1970–79) resulting from a declining economy, the refocusing of the federal government on other matters; and the changing dynamics that characterized federal-provincial relations at the end of the decade. During the Conservative regime that lasted for ten years from 1984 to 1994, the Conservatives had almost totally refrained from engaging in urban or municipal spending.

The re-emergence of urban and municipal concerns at the federal level and the strong support from the Liberals to the municipalities in the mid-1990s were not purely accidental or surprising. Municipal governments, through the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) and the Big City Mayors Association, have played an important role in stimulating changes in Canadian federalism. Since its creation in 1976, the FCM has maintained a strong advocacy role in lobbying for the federal government to include municipal issues in policy development and federal decision making. The FCM has pressured the federal government to influence policy and funding decisions and to make the municipal governments a legitimate level of government in Canadian intergovernmental relationships, with more or less success.

Since 1980 the FCM has sought the recognition of municipalities as a “distinct level of government under the new constitution” (Dewing et al. 2006, 10). Within the context of realizing its primary goal of constitutional recognition and in furthering its role of active involvement in the country’s economic and political spheres, the FCM has devoted its efforts to lobbying for practical and specific services. To strengthen the influence of its lobbying activities, the FCM had established several task forces whose main duties were to devise a municipal point of view on national issues that affected its members. It has been intensively pursuing more federal spending on infrastructure through lobbying.

Since its creation, the FCM has had a stronger influence on the Liberal Party than on the Conservative Party. The strong support of the Liberals for the FCM’s advocacy was further fortified when in 1986 John Turner, then the Liberal Party’s leader of the opposition, endorsed the FCM’s proposal for increased funding, which enabled the creation of the National Liberal Task Force on Municipal Infrastructure in 1989. It conducted a survey that found that at least $25.1 billion was needed to effectively upgrade municipal infrastructure (Swimmer, cited in Hilton 2007, 47). This conclusion was used by the FCM to buttress their proposal for increased funding, which was eventually used by the Liberals in its 1993 electoral platform entitled Creating Opportunity: The Liberal Plan for Canada (also known as the Red Book). The Red Book outlined four objectives for a tripartite shared-cost infrastructure program between the federal, the provincial, and the municipal levels. The objectives were creating jobs, supporting economic growth, enhancing community livability, and building intergovernmental cooperation.

Shortly after the election, the federal government fulfilled its promise and created the Canada Infrastructure Works Program (CIWP). It had funding support of $6 billion for the creation of both short- and long-term jobs and the enhancement of communities’ physical infrastructure. The program identified four factors that supported this federal initiative to invest in local infrastructure (Jennings 2003):

1 Targeted investment in infrastructure can produce a general economic stimulus, with short-term employment in construction likely to be the main impact.

2 Investment in infrastructure can produce longer-term positive effects on productivity and employment as a result of, for example, improved transportation facilities and communications.

3 Infrastructure needs to be upgraded. Before the introduction of the program, concerns had been raised about the state of local infrastructure in Canada.

4 The limited resources available to governments to undertake the large investments involved in infrastructure imply that all three levels of government benefit from a coordinated, joint approach.

In 1994, the program was put into operation as a temporary $2 billion shared-cost program with the objective of “assisting in the maintenance and development of infrastructure in local communities and the creation of employment” (Barrados et al. 1999). The funds were allocated to provinces, territories, and First Nations based on population and unemployment numbers. The federal government entered into individual negotiations and agreements with each province and territory to implement the program; negotiations were undertaken through a joint federal-provincial management committee for each province or territory. Typically, the federal government would provide one-third of the cost, and the provincial and municipal governments would be responsible for the other two-thirds. Even though the provinces were in principle responsible for the final selection of projects, the federal government played an influential role in setting up the criteria and the guidelines for project selection. In other words, the federal government could approve or refuse the projects proposed by the province.

In the 1996 Report of the Auditor General, it was found that over 12,000 projects were approved, with eligible costs of about $6.5 billion and a total federal share of $1.9 billion (Blain et al. 1996). According to some estimates, 120,000 jobs were created under the program (Jennings 2003).

While the program was politically rewarding, the design and the implementation of the program was questioned in the 1999 auditor general’s report. For instance, the report highlighted the temporary nature of the program and raised questions about the sustainability of infrastructure spending by the federal government. It also identified the lack of the federal government capacity to fully exercise its responsibilities and accountability obligations on shared-delivery arrangements with the provinces. In 2000 the time was ripe for another round of debates about the role of the federal government in municipal infrastructure spending.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE FEDERAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM FROM 2002 TO 2010

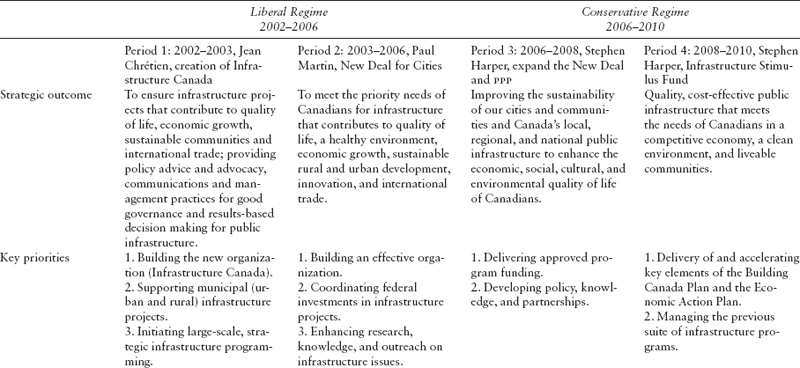

Table 7.1, at the end of this chapter, summarizes the evolution of the Federal Infrastructure Program in Canada from 2002 to 2010. Over that period of political turbulence, which saw three different prime ministers lead the country, the federal infrastructure program evolved from its modest beginnings during the period 1994 to 2002 to become a significant federal agenda item across all political spectrums.

The Creation of Infrastructure Canada (2002–04)

In August 2002, towards the end of his ten-year reign as the prime minister of Canada, Jean Chrétien created a new department, Infrastructure Canada, in order to provide a focal point for the government of Canada to administer the various infrastructure-funding programs, to provide collaboration with the government’s partners on infrastructure policy issues, and to increase the knowledge base about public infrastructure in Canada (Infrastructure Canada 2007a). During that early period the federal government was focusing, for the most part, on the linkage between infrastructure and economic growth, whereby the ministry would play a catalyst role in “building partnerships among all levels of government and other sectors to achieve shared infrastructure goals,” through innovation, environmental sustainability, and a consistent focus on the specific realities and needs of communities all across Canada (Infrastructure Canada 2003).

During its first year of existence, Infrastructure Canada invested mostly in water and wastewater treatment systems, highways, local transportation, culture, recreation, and broadband communications projects. In the policy documents from 2002–03, the official raison d’être of the program was to respond to the “large pressing infrastructure needs in Canada” stemming from the existence of the sizeable gap between the existing infrastructure stock and the needs of municipalities and their populations (Infrastructure Canada 2003). The program was mandated to collaborate with different stakeholder groups, such as local, provincial, and territorial governments and federal departments and agencies, First Nations, universities and research institutes, members of the private sector, and other experts.

At that time, the federal infrastructure initiatives managed by Infrastructure Canada were rationalized into four main programs:

• The Infrastructure Canada Program (ICP), with federal funding of $2.05 billion.

• The Canada Strategic Infrastructure Fund (CSIF), with federal funding of $2.0 billion.

• The Border Infrastructure Fund (BIF), with federal funding of $600 million.

• The Affordable Housing Program, with federal funding of $680 million.

These initiatives were undertaken concurrently with other existing infrastructure initiatives such as the FCM Green Funds, managed by the Ministry of Environment; the Strategic Highways Infrastructure Program (SHIP); managed by Transport Canada; and the Cultural Spaces Canada Program, managed by Heritage Canada.

During that early period, the program objectives in infrastructure development and management were not very clear. The priorities and targets remained relatively vague, and the infrastructure agenda was mainly set by the provinces and the municipalities, not by the federal government. The lack of a clear national federal agenda is probably one of the weakest elements of the federal involvement in infrastructure spending. This situation still remains, as we will see later, as the Achilles heel of the infrastructure program today.

The New Deal for Cities and Communities (2004–06)

When Paul Martin took over from Jean Chrétien as prime minister of Canada in November 2003, expectations for a new approach to intergovernmental relations between the federal government, the provinces, and the municipalities were high. Paul Martin’s New Deal for Cities and Communities was one of his top priorities.

He had committed to providing considerable and stable federal funding for Canadian municipalities, and he seemed determined not to disappoint. His first cabinet included a position for a minister of state that placed Infrastructure Canada in the Ministry of Environment portfolio. John Godfrey was named minister of state of infrastructure and communities, an appointment that was considered a significant, since Godfrey was reputed to be interested in urban issues (Johnston 2004). The move to the Ministry of Environment portfolio involved new federal objectives such as sustainable development, climate change, health, and innovation (Infrastructure Canada 2004).

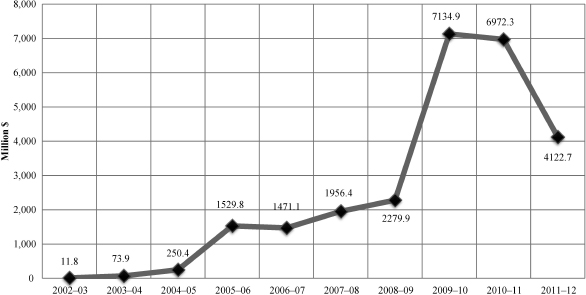

During the fiscal year 2004–05, with the conclusion of an agreement on a gas tax with the provinces and territories, the concrete results of a new deal became a reality. This initiative had an immediate impact on the annual departmental budget. The total financial resources for the department increased from $74 million in the financial year 2003–04 to $250 million in the financial year 2004– 05 (figure 7.1). The number of full-time equivalent employees at Infrastructure Canada rose from 92 to 179 (figure 7.2).

The New Deal for Cities and Communities aimed to establish predictable and stable long-term funding for cities and communities (Infrastructure Canada 2004). The $5 billion of total funding was expected to be allocated over a five-year period starting in 2005 and to be based on a per capita distribution (Ventin 2005, 1). The funds were to be allocated to support environmentally sustainable municipal infrastructure such as water and wastewater systems, public transit, community energy systems, solid waste management, the rehabilitation of roads and bridges, and capacity building, which envisioned the improvement of the environmental quality of Canada through decreased greenhouse gas emissions and cleaner air and water. The FCM also supported the per capita allocation approach. Moreover, its involvement in pre-budget meetings fortified the government’s commitment to acknowledge municipal governments as partners in the execution of the national agenda (Ventin 2005).

Figure 7.1 Total Financial Resources, Infrastructure Canada, 2002–12. Data for 2009– 10, 2010–2011, and 2011–12 are estimates. Sources: Infrastructure Canada Departmental Performance Reports 2002–03 to 2008–09 and Infrastructure Canada Reports on Plans and Priorities, 2009–10

The Conservative Plan for Improving Canada’s Infrastructure (2006–2008)

On 24 January 2006, Paul Martin conceded defeat to Stephen Harper and the Conservative Party in the thirty-ninth Canadian general election held on 23 January 2006. Harper had to form a minority government shortly after his victory. In its 2006 federal election platform, the Conservative Party was more committed to supporting infrastructure than ever before. As a matter of fact, in its previous election platform in 2004, Demanding Better, there was almost no provision or vision for city infrastructure (Conservative Party of Canada 2004). In the 2006 platform, called Stand Up for Canada, the Conservative Party adopted an approach that appealed to the city lobby and was clearly in line with the recent policies of the Liberal Party. Instead of opposing the Liberal Party on the New Deal for Cities, the Conservatives actually proposed to expand the New Deal using the gas tax to increase transfers and include more cities in the program (Conservative Party of Canada 2006).

Figure 7.2 Full-time Equivalent Employees, Infrastructure Canada, 2002–10. Data for 2009–10 are estimates. Sources: Infrastructure Canada Departmental Performance Reports 2002–03 to 2008–09 and Infrastructure Canada Reports on Plans and Priorities, 2009–10.

In its electoral platform, the Conservative Party proposed an approach that aimed at “fixing Canada’s infrastructure deficit” (Conservative Party of Canada 2006), insisting not only on “municipal infrastructures” but also on roads, highways, and border crossings as well. The Conservatives proposed supplementing the New Deal with municipal transfer payments equivalent to five cents per litre by 2009–10. This gas tax transfer was intended to build and repair roads and bridges, to improve safety, and fight traffic congestion. In addition to maintaining the existing federal infrastructure agreements with provinces and municipalities, the federal government would negotiate a new infrastructure agreement with provinces to provide a stable, permanent Highways and Border Infrastructure Fund.

Budget 2007 included an allocation for the extended Gas Tax Fund (GTF) from 2010 to 2014 of $2 billion per year, for a total of $8 billion in new predictable funding directed at sustainable infrastructure. Thus, a total of $13 billion was allocated for the period of 2005 to 2014. This stable funding will support municipal infrastructure projects that are environmentally friendly and enhance quality of life. Stable funding will allow municipalities to make long-term financial commitments and undertake long-term planning (Infrastructure Canada 2007b). On an annual basis, the total financial resources spent by Infrastructure Canada increased steeply between the fiscal years 2002–03 and 2007–08. The increase from $11 million in 2002–03 to $2.9 billion in 2007–08 (figure 7.1) is largely due to the impact of the Gas Tax Fund.

With the victory of the Conservatives, the federal infrastructure policy orientation shifted towards transportation issues. On 6 February 2006, Transport Canada, Infrastructure Canada, and sixteen Crown corporations were brought together in a single portfolio in the Ministry of Transport, Infrastructure and Communities under the leadership of Lawrence Cannon. Cannon emphasized that the Government would support infrastructure that maximized value for taxpayers’ money and enhanced the economic, social, cultural, and environmental quality of life of Canadians (Infrastructure Canada 2006a, 2006b). Then in June 2006 the FCM released a new study known as “Restoring Municipal Fiscal Balance” that slightly redefined the issue. For the FCM, the municipalities are squeezed between increasing responsibilities, on one hand, and a stagnation of the fiscal resources available to respond to the needs of the Canadian population on the other. The problem is not limited to the infrastructure deficit; the FCM argued that it is structurally related to the current definition of the roles and responsibilities of governments in the current Canadian intergovernmental system. The FCM pleaded for a bottom-up approach, based on the “subsidiarity principle,”3 to fixing economic, social, and infrastructure problems, with the municipal level included in the national fiscal imbalance debate. From then on, the FCM started lobbying for a long-term legislative approach that would guarantee steady additional revenues to the municipalities.

In 2007 the Conservative government released its new policy on infrastructure, Building Canada – Modern Infrastructure for a Strong Canada (Infrastructure Canada 2007c), which was developed from the federal government’s long-term economic plan, Advantage Canada,4 released by the Conservatives in the previous year. Five “advantages” noted in this economic plan are tax, fiscal, entrepreneurial, knowledge, and infrastructural advantages. The infrastructure advantage is said “to ensure the seamless flow of people, goods and services.” Building Canada is referred to as “the largest single federal commitment to public infrastructure of this type.” The federal government will invest $33 billion between 2007 and 2014 to implement the “infrastructure advantage” objectives. The Building Canada Plan focuses on three dimensions: economic, environmental, and community perspectives. The document argues that because the country’s overall level of productivity is affected by the state of its infrastructure, if the country’s infrastructure is less than adequate, it is likely to deter foreign investors. The document also explains that infrastructure is one of the major factors for attracting skilled and knowledgable workers in urban areas.

In its economic dimension, Building Canada directs investments to projects that will increase trade, ensure easy movement of people and goods, and maintain economic growth. Specific areas of infrastructure investment that would benefit the economic growth of Canada are gateways and borders, highways, short-line rail and short-sea shipping, connectivity and broadband, tourism, and regional and local airports. In its environmental dimension, the Building Canada Plan claims that “the federal government has set the protection and promotion of a clean environment as a paramount national objective.” A major instrument in ensuring this objective is upheld is the investment in infrastructure that is environmentally orientated. The plan also includes a community perspective to attract and retain both a skilled workforce and private sector investments. Specific areas of infrastructure investment to promote strong and healthy communities are drinking water; disaster mitigation; brownfield redevelopment; roads and bridges; and sports and culture.

The Building Canada Plan calls for $17.6 billion of “based funding” – meaning stable and predictable revenues (Infrastructure Canada 2007c) – through tax transfers and rebates to be provided to municipalities over a period of the seven years from 2007–14. The based funding will be delivered in two types of funds: a Gas Tax Fund and a GST Rebate. The Gas Tax Fund amounts to $11.8 billion (from 2007–08 to 2013–14) and allows municipalities to pool, bank, and even borrow against it. In Budget 2008, the government announced that the program would become a permanent measure beyond 2013–14, but the share would be topped at $2 billion per year. It is a conditional grant designed to support only environmentally sustainable municipal infrastructure projects such as public transit, drinking water, wastewater infrastructure, green energy, solid waste management, and local roads and bridges, etc. (Infrastructure Canada 2010).

Municipalities will also be held accountable for their spending of the Gas Tax Fund and are expected to report to the federal government each year. In principle, the federal government requires that municipalities develop an Integrated Community Sustainability Plan (ICSP) to ensure that projects support sustainability principles guided by community consultation and a long-term plan (Hawke and Purcell 2007). Although the ICSP is conceived as the main monitoring tool for the federal government over the investments, not all provinces or territories need to choose to adopt such a plan. Many provinces already have sophisticated municipal regulatory frameworks and accountability systems, which include medium- and long-term planning and participatory mechanisms, along with multi-year capital infrastructure plans. So in most provinces, municipalities don’t have to develop an original ICSP and are required only to demonstrate that they have already developed the appropriate planning instruments and processes. In Ontario, for instance, municipalities have only to show compliance with ICSP requirements (Province of Ontario and Government of Canada 2005). In the Alberta, the Alberta Urban Municipalities Association (AUMA) has developed its own ICSP template to present information about the compliance with federal requirements (AUMA 2010). In the case of Quebec, there is no reference to any compliance with federal requirements. In the agreement for the transfer of federal gas tax revenues to Quebec, all obligations contracted by Quebec are subject to provincial legislation, and the obligation to comply with the ICSP is not mentioned anywhere. In contrast, in the territories where strategic planning was not well established, the ICSP is proving to be a useful tool. In the Northwest Territories, for instance, all thirty-three communities have developed an ICSP as part of the Gas Tax Fund Agreement. We can thus observe that federal accountability mechanisms vary significantly from one province or territory to another. However, for some authors, such as Hilton and Stoney (2009), the attempt by the federal government to intervene in community planning is dangerous and perverse, since it clearly crosses the jurisdictional responsibilities of provinces and municipalities.

The GST Rebate accounts for $5.8 billion, to be put towards new infrastructure or to the maintenance of existing infrastructure. It is basically a full refund of the GST paid by municipalities. There is no requirement for municipalities to be accountable to the federal government for their GST Rebate spending.

The Building Canada Plan also includes three new infrastructure programs:

• The Gateways and Border Crossings Fund ($2.1 billion)

• The Building Canada Fund ($8.8 billion)

• The Public-Private Partnership Fund ($1.25 billion)

The Gateways and Border Crossings Fund is targeted toward national priorities, focusing on strategic trade corridors. The sum of $2.1 billion will fund infrastructure, with an emphasis on international gateways such as international bridges and tunnels and short-sea shipping. This program does not directly target municipal infrastructures, but most of these infrastructures will affect several rural or urban municipalities. The Building Canada Fund dedicates $8.8 billion for both publicly and privately owned infrastructures, and allocations will be based on the 2006 Census population information for each province and territory. Most of the major infrastructure components of the fund are directed towards the larger projects of national priority. The Community Component is for projects in communities having populations of less than 100,000 and is meant to complement the Gas Tax Fund. Up to 1 percent of the funding for both the major infrastructure component and the community component will be designated for infrastructure research, planning, and capacity building. The Building Canada Plan also calls for each province and territory to sign a framework agreement with the federal government to ensure that the long-term planning of infrastructure issues is addressed.

The most important policy change of the Conservatives’ plan is the Public-Private Partnership Fund, which is designed to target national infrastructure investment priorities. As stated in the Building Canada document, “private capital and expertise can make a significant contribution to building infrastructure projects faster and at a lower cost to taxpayers. The private sector is also often better placed to assume many of the risks associated with the construction, financing, and operation of infrastructure projects.” While public-private partnership (P3) initiatives have been used in Canada previously – as was the case with the Confederation Bridge and the Canada Line transit project – the Conservative government wishes to match the global expansion of the use of P3 projects in the area of infrastructure.

P3s will be developed through two initiatives. The $1.25 billion Public-Private Partnerships Fund will flow towards projects that seek alternative financing beyond the traditional procurement process. The P3 Fund seeks to attract private-sector funding sources, and $25 million will be devoted to setting up a P3 office to facilitate and identify ongoing P3 opportunities. The Building Canada Plan stipulates that the Gateways and Border Crossings Fund and the Building Canada Fund give primary consideration to P3s for large infrastructure investment projects. Because “all projects seeking $50 million or more in federal contributions will be required to assess and consider the viability of a P3 option,” the federal P3 office will oversee the processes involved.

Municipal Infrastructure Spending as an Economic Stimulus Fund (2008–2010)

Despite a previous commitment from the Conservative Party to set fixed election dates, Prime Minister Harper decided to dissolve his government and to launch a general election on 7 September 2008. Officially, the Harper government was arguing that it was impossible to manage the affairs of the country as a minority government and urged the population to elect a majority. There were many strategic reasons beyond the official reason, as well. Conservative strategists argued that the timing was good for an election call, since the Harper government was relatively popular at the time. The fortieth general election took place on 14 October, but the Conservatives could not reach their goal of winning a majority, although they did win a stronger minority, with 143 seats, as against 127 at the dissolution. John Baird, former minister of the environment and president of the treasury board in Harper’s cabinet became the new minister of transport and infrastructure, replacing Lawrence Cannon.

However, there was more to come. The United States had already entered into a severe recession that was about to hit Canada’s economy. In Harper’s electoral platform, The True North Strong and Free (Conservative Party 2008a), the proposed economic plan for facing the economic crisis was philosophically conservative and included balanced budgets, lower taxes, investments to create jobs, and measures to maintain a low rate of inflation. Increased government spending was not an option for the new government, despite the risks of a severe global economic crisis, nor was it a strong economic stimulus plan. The platform committed to maintaining the same level of effort in infrastructure spending, while following the same guidelines adopted in 2007 in the Building Canada Plan. The only new element in the platform was the commitment to continuing the Gas Tax Transfer to municipalities at a permanent level of $2 billion annually beyond 2014. But the new government was resolute on governing with a conservative agenda based on the policy declaration adopted by the National Convention on 15 November 2008 (Conservative Party 2008b).

The Conservative Party had revised the infrastructure strategy after experiencing pressure from the international community and from the three opposition parties, which threatened to create a coalition in order to bring down the newly elected government. The Conservative government had no choice but to develop and adopt an extensive economic stimulus plan: Canada’s Economic Action Plan (Government of Canada 2009), which was released in March 2009. The plan included a massive investment in infrastructure. Originally, it aimed to inject about $12 billion of funding over a two-year period for infrastructure projects, in order to support the effort to emerge from the global economic crisis. Since most of these projects included joint funding with provinces and municipalities as a basic requirement, the government believed that the injection of money in infrastructure in Canada was likely to exceed $20 billion between 2009 and 2011. The goal was to create as many jobs as possible while providing a more modern and more environmentally friendly infrastructure stock throughout Canada. The plan was not limited solely to including municipal infrastructures. Four types of infrastructure projects were eligible:

• Provincial, territorial, and municipal projects ($6.4 billion)

• First Nations infrastructure ($0.5 billion)

• Knowledge infrastructure ($3.1 billion)

• Federal infrastructure ($0.7 billion)

In the context of the economic stimulus package, the infrastructure strategy of the government of Canada relied on two types of action (Infrastructure Canada 2009b): (1) accelerating federal approvals through the Building Canada Plan adopted in 2007 ($33 billion over seven years) and (2) creating a new Infrastructure Stimulus Fund ($4 billion over two years) and a new Green Infrastructure Fund ($1 billion over five years) through the Canada’s Economic Action Plan adopted with Budget 2009. The Building Canada Plan was actually designed to provide medium- to long-term municipal infrastructure spending between 2007 and 2014. Because of the recession, Infrastructure Canada undertook several initiatives to accelerate investments under the plan, including making regulatory changes under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act to allow the substitution of a provincial environmental assessment process for the federal process in order to reduce duplication and delays. It also accelerated federal review for approval of projects, simplifying the criteria and reducing the amount of information required in the application process. These measures are also rather typical of the Conservative government, which often seeks to reduce regulations to stimulate market mechanisms.

The $4 billion stimulus fund is developed to help the realization of construction-ready infrastructure projects. It focuses especially on rehabilitation projects but also on new construction projects that can start quickly. The federal government indicated that eligible projects under this fund must be launched before and finished by 31 March 2010. The main goal was to create jobs fast enough to counter the economic slowdown. The $4 billion is allocated based on the population of each province and territory. However, if a province or territory is not progressing quickly enough, the federal government can reallocate the funding to another province or territory. The goal is to inject money quickly into the economy to create jobs.

Through the Economic Action Plan of Canada, the federal government also created a new $1 billion dollar fund to be spent over five years in a Green Infrastructure Fund. The fund is intended to support projects that promote clean air and water emissions and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These projects fall within the following categories: sewage treatment, infrastructure production of green energy, transportation infrastructure, municipal solid waste treatment and storage of carbon dioxide. The program is not exclusive to municipalities or public organizations. Eligible organizations include provinces, territories, and local governments or regional organizations, but also non-profit organizations and private companies (Infrastructure Canada 2010).

Figure 7.1 clearly shows the drastic increase in total financial resources spent by Infrastructure Canada from 2009 to 2011, followed by a steep decrease from 2011 to 2012. The amount that will be recurrently spent in municipal infrastructure by the federal government after 2012 will be twice the amount that had been spent just three years earlier.

Meanwhile, the FCM has continued to advocate for an injection of funds in municipal infrastructures. In November 2007, the FCM released the report named Danger Ahead: The Coming Collapse of Canada’s Municipal Infrastructure (Mirza 2007). This report, written by Saeed Mirza, professor at the Department of Civil Engineering and Applied Mechanics at McGill University, is somewhat alarmist. It argued that the physical foundations of municipalities across Canada were near collapse, since Canada’s infrastructure had exceeded about 79 percent of its useful life, and it set the infrastructure deficit at $123 billion. Fifty-nine percent of all Canadian infrastructures were more than forty years old and needed exhaustive maintenance to avoid collapsing, while new municipal infrastructures were also needed. In 2008, the FCM released another report entitled The Macroeconomic Impacts of Spending and Level-of-Government Financing (Sonnen 2008). This report, written by Carl Sonnen, from the private firm Informetrica, sought to demonstrate that in the context of the recession, the acceleration of infrastructure spending was the best way to stimulate the economy. It explained that tax cuts would not produce as many jobs and stimulate the economy as much as investment in infrastructure, pointing out that every investment of $1 billion in infrastructure would create more than eleven thousand jobs. Based on that report, the FCM suggested to the federal government that it should accelerate and invest massively in municipal infrastructures to reduce the negative impact of the recession.

Since the beginning of the economic crisis of 2008, the federal government has considered the municipalities as part of the solution to limiting the impact of the crisis on the Canadian economy, and infrastructure investments provide a good example. The federal government solutions and those from the FCM have been quite similar since the beginning of the economic crisis. Through the Economic Action Plan, the government has worked closely with provinces, territories, and municipalities – through the FCM – to quickly approve as many projects as possible and to ensure that the work on infrastructure starts as quickly as possible. For example, in developing the strategy, the minister of transport and infrastructure has consulted the municipal sectors directly and made them full partners in implementing the Economic Action Plan (Infrastructure Canada 2009a). Minister Baird has also co-signed an open letter to Canadian municipalities released on 9 April 2009 with the president of the FCM at the time, Jean Perreault. This letter is a joint initiative between the government of Canada and the (FCM) to provide an update on the development and implementation of new federal infrastructure programs available to municipalities. The letter also seeks to encourage municipalities to prepare plans and submit funding requests. This is a new step towards a more direct collaboration between the federal government and municipalities that avoids going through the provinces or territories in the process.

CONCLUSION

So what explains the rise of multilevel governance between the federal government and Canadian municipalities across party lines? To provide an answer to this question, we have studied the evolution of the federal infrastructure program before and after the creation of Infrastructure Canada in 2002.

First, it can be claimed that the municipal lobby led by the FCM has been rather effective since the mid-1990s. If the FCM was traditionally more successful in persuading the Liberal Party of the benefits of investing in municipal infrastructures, it appears that nowadays municipal infrastructure spending is equally a key part of both the Conservative and the Liberal political agendas. This is a very significant change. Since the Conservative government came into power, it has been committed to maintaining the infrastructure program and expanding it in the future.

Has the political (electoral) reward of municipal spending been a key incentive for increased participation by the federal government in municipal infrastructure projects? Since the mid-2000s, municipal infrastructure spending has become a political strategy that both Liberal and Conservative parties are not ready to give up on. It appears that the Conservative party made informed electoral calculations since the 2004 election, when they offered little to almost nothing to the municipalities at the time. The Conservatives now seem to think that the issue of “infrastructure deficit” can be a safeguard for them to avoid being seen negatively by the municipalities in comparison to the opposition parties. In this context, the municipal lobby led by the FCM is likely to remain in a position of strength in the near future at least.

Second, it seems obvious that the provinces largely tolerate the involvement of the federal government in municipal affairs, since the provinces and the municipalities are under-financed and any additional source of revenue is welcome. In fact, there is not much open controversy about the federal transfers as long as the federal government engages in negotiations with the provinces and signs agreements with them.

Few people now deny that the municipal infrastructure deficit in Canada is alarming coast-to-coast. However, the relevance of these new multilevel intergovernmental arrangements and the general trends of the current federal infrastructure policies can also be debated. For many years, the federal government has been swimming in a budgetary surplus, but this situation has changed rather radically since 2008–09. Politically, the questions of whether or not the right governance arrangements are in place and of whether the current federal infrastructure policies are relevant have not yet fully been answered.

As it is, the general intergovernmental arrangement is based on conditional transfers: the federal government collects taxes for another level of government that spends it under certain criteria. Often, the allocations use a per capita funding formula instead of a redistributive approach. Because there is a general lack of policy guidelines for choosing what project to finance, infrastructure program has often adopted an “ad hoc approach,” according to Hilton (2007). It is structured around relatively short- or medium-term commitments from the federal government. If the economic situation in Canada deteriorates along with its fiscal capacity, then the level of transfers could change relatively rapidly, which would hardly be compatible with the long-term amortization of investments required to fund medium- and large-scale municipal infrastructures, along with the cost of infrastructure maintenance.

In the future, the federal government infrastructure policy could have an even greater influence on municipal management if the federal contribution to infrastructure spending is done through public-private partnerships (P3s). The Infrastructure Canada 2007–2008 Report on Plans and Priorities argues that “P3s can deliver public infrastructure more efficiently, i.e. lower cost, faster completion, and better management of project risks. At the same time, appropriate public control can be preserved” (Infrastructure Canada 2007b, 19). On the surface, it appears that the federal government wants to distance itself from the public management of infrastructure by promoting P3s. The present government seems to believe that large infrastructure projects can be better managed by public-private cooperation, but recent research suggests that this is not necessarily always the case (Hamel 2007).

The current arrangement raises several issues related to the fiscal accountability framework. When one government spends fiscal resources raised by another level of government, the taxpayer may find it difficult to identify who is ultimately responsible for the infrastructure development in question. Fiscal federalism theory says that finance should follow function and that expenditure assignment should match the appropriate level of responsibilities. Right now, the shared arrangements present some gaps in terms of the roles and responsibilities among governments, at least from the point of view of the taxpayers. From the point of view of the municipalities, the current model is still characterized by a lack of predictability in terms of resources for municipal budgets. About half the current level of federal municipal infrastructure spending is not guaranteed after 2014. Although the government has announced the extension of the Gas Tax Fund beyond 2013–14, this is only a political engagement that could be compromised by new economic circumstances or by a change of political regime. But most of all, the current intergovernmental arrangement model does not address the question of local autonomy. The Federal Municipal Infrastructure Program remains largely a sponsoring arrangement that tends to maintain municipal dependence on federal grants rather than encourage subnational government autonomy.

Finally, my analysis reveals that the Federal Municipal Infrastructure Program was clearly a political opportunity to consolidate the role of the federal government in municipal affairs. This conclusion is further substantiated by the growing role of the FCM as a strong lobbyist. In the past few decades, the FCM has influenced many policies and decisions related to municipal issues, including many that have fully legitimized the role of Canadian municipal governments in intergovernmental relationships. The FCM has strongly advocated that the issues of maintaining and repairing existing roads, bridges, and overall transportation management while adding world-class infrastructure must be addressed by all layers of governments. Overall, the federal municipal infrastructure investments have been a new step in this direction and have definitely opened the door to renewed intergovernmental arrangements in Canada. Since the creation of the first municipal infrastructure program by the Liberal Party in the mid-1990s until the Conservatives’ involvement in this issue, municipal infrastructure spending has been a laboratory for more direct collaboration and partnership between the federal government and municipalities and for a concrete transformation of Canadian intergovernmental practices.

Table 7.1 Evolution of Strategic Outcomes and Priorities from 2002 to 2010

Sources: Infrastructure Canada, Departmental Performance Reports, 2002–2003to 2008–2009, and Report on Plans and Priorities, 2009–2010.

1 The debate over the municipal infrastructure deficit has been strongly advocated by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM).

2 This text was written before the re-election of the Conservative Party for a third consecutive time as a majority government in the aftermath of the forty-first Canadian general election held Monday, 2 May 2011. The policy framework has remained relatively consistent since that election.

3 The FCM proposes the following definition: “the principle of subsidiarity suggests that since municipal governments are more familiar, visible, and accessible to Canadians, they are often in the best position to make the most informed and efficient decisions on the delivery of key public services” (FCM 2006, 33).

4 Advantage Canada is the Conservatives’ long-term, national economic plan designed to make Canada a world economic leader. The plan, unveiled by Minister Flaherty in his annual budget in 2006, features new national targets to eliminate Canada’s total government net debt in less than a generation and to further reduce taxes on businesses and citizens, thereby reducing unnecessary regulation for businesses, creating a competitive and flexible work force, and investing in infrastructure.

REFERENCES

Andrew, Caroline, Katherine A. Graham, and Susan D. Phillips, eds. 2002. Urban Affairs: Back on the Policy Agenda. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

AUMA. 2010. Integrated Community Sustainability Plan Template. Accessed 27 June 2010, http://www.auma.ca/live/digitalAssets/35/35287_ICSP_template_2010.pdf.

Barrados, Maria, Henno Moenting, Jim Blain, Louise Grand’maison, Jayne Hinchliff-Milne, Raymond Kuate-Konga, Pierre Labelle, and Joanne Moores. 1999. Canada Infrastructure Works Program Phase II and Follow-up of Phase I Audit. Report of the Auditor General. Accessed 14 November 2007, http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/domino/media.nsf/html/99pr17_e.html.

Berdahl, Loleen. 2004. “The Federal Urban Role and Federal Municipal Relations.” In Municipal-Federal-Provincial Relations in Canada, edited by Robert Young and Christian Leuprecht. Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Blain, James S., Sophie Chen, Gerry Chu, Louise Grand’maison, Sylvie Soucy, and Peter Yeh. 1996. Canada Infrastructure Works Program: Lessons Learned. Report of the Auditor General. Accessed 14 November 2007, http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/domino/reports.nsf/html/9626ce.html#0.2.Q3O5J2.O25UY6.QCTLQE.NS.

Bojorquez, Fabio, Eric Champagne, and François Vaillancourt. 2009. “Federal Grants to Municipalities in Canada: Nature, Importance and Impact on Municipal Investments, from 1990 to 2005.” Canadian Public Administration 52 (3): 439–55.

Bradford, Neil. 2004. “Place Matters and Multilevel Governance: Perspectives on a New Urban Policy Paradigm.” Policy Options, 39–44.

Conservative Party of Canada. 2004. “Demanding Better.” Electoral platform of the Conservative Party of Canada in the 2004 federal election.

– 2006. “Stand Up for Canada.” Electoral platform of the Conservative Party of Canada in the 2006 federal election.

– 2008a. “The True North Strong and Free.” Electoral platform of the Conservative Party of Canada in the 2008 federal election.

– 2008b. “Policy Declaration.” Accessed 28 April 2010, http://www.conservative.ca/media/2008-PolicyDeclaration-e.pdf.

Dewing, Michael, William Young, and Erin Tolley. 2006. Municipalities, the Constitution and the Canadian Federal System. Accessed 14 November 2007, http://www.parl.gc.ca/information/library/PRBpubs/bp276-e.pdf.

Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM). 2006. Building Prosperity from the Ground Up: Restoring Municipal Fiscal Balance, 96. Ottawa: FCM.

Government of Canada. 2009. Canada’s Economic Action Plan: A First Report to Canadians. Accessed 17 April 2010, http://www.actionplan.gc.ca/grfx/docs/ecoplan_e.pdf.

Hamel, Pierre J. 2007. Les partenariats publics-privés (PPP) et les municipalités: au-delà des principes, un bref survol des pratiques. INRS-Urbanisation, Culture et Société.

Hawke, Baxter, Kelly Purcell, and Mike Purcell. 2007. “Community Sustainability Planning.” Municipal World, November: 35–8.

Hilton, Robert N. 2007. “Building Political Capital: The Politics of ‘Need’ in the Federal Government’s Municipal Infrastructure Programs.” MA thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario.

Hilton, Robert, and Christopher Stoney. 2009. “Federal Gas Tax Transfers: Politics and Perverse Policy.” In How Ottawa Spends 2009–2010: Economic Upheaval and Political Dysfunction, edited by Allan M. Maslove. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Infrastructure Canada. 2003. Performance Report for the Period Ending 31 March 2003.

– 2004. Performance Report for the Period Ending 31 March 2004.

– 2005. Performance Report for the Period Ending 31 March 2005.

– 2006a. Departmental Performance Report for the Period Ending 31 March 2005.

– 2006b. Report on Plans and Priorities (RPP): 2006–2007.

– 2007a. Accessed 17 October 2007, http://www.infrastructure.gc.ca.

– 2007b. Report on Plans and Priorities (RPP): 2007–2008.

– 2007c. Building Canada: Modern Infrastructure for a Strong Canada.

– 2008a. Departmental Performance Report for the Period Ending 31 March 2007.

– 2008b. Report on Plans and Priorities (RPP): 2008–2009.

– 2009a. Departmental Performance Report for the Period Ending 31 March 2008.

– 2009b. Report on Plans and Priorities (RPP): 2009–2010.

– 2010. Accessed 17 Apri 2010, http://www.infrastructure.gc.ca.

Jennings, Marlene. 2003. The Liberal Government: Investing in Infrastructure, Investing in Communities. Accessed 14 November 2007, http://www.marlenejennings.parl.gc.ca/issue_details.asp?lang=en&CatID=29&IssueID=328.

Johnston, Geoffrey. 2004. “Can Paul Martin Be Our City’s Saviour?” Kingston Whig-Standard, 22 January.

Kitchen, Harry M. 2002. Municipal Revenue and Expenditure Issues in Canada. Canadian Tax Paper No. 107. Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation.

Liberal Party of Canada. 1993. “Creating Opportunity: The Liberal Plan for Canada.” Electoral platform of the Liberal Party of Canada in the 1993 federal election.

McAllister, Mary Louise. 2004. Governing Ourselves: The Politics of Canadian Communities. Vancouver: UBC Press.

McMillan, Melville L. 2006. “Municipal Relations with the Federal and Provincial Governments: A Fiscal Perspective.” In Canada: The State of the Federation 2004, Municipal-Federal-Provincial Relations in Canada, edited by Robert Young and Christian Leuprecht. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press for the Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University.

Mirza, Saeed. 2007. Danger Ahead: The Coming Collapse of Canada’s Municipal Infrastructure. Federation of Canadian Municipalities, 24.

Privy Council Office. 2001. “Prime Minister’s Caucus Task Force on Urban Issues Announced.” Accessed 15 November 2007, http://www.pco-bcp.gc.ca/default.asp?Language=E&Page=archivechretien&Sub=newsreleases&Doc=urbantaskforce_20010509_e.htm.

Province of Ontario and Government of Canada. 2005. Agreement for the Transfer of Federal Gas Tax Revenues under the New Deal for Cities and Communities, 2005–2015.

Province of Quebec and Government of Canada. 2005. Gas Tax Agreement Canada-Quebec 2005–2015, Final Agreement.

Sancton, Andrew, and Robert Young. 2003. “Paul Martin and Cities: Show us the Money.” Policy Options (December 2003–January 2004): 29–34.

Slack, Enid. 2002. “Have Fiscal Issues Put Urban Affairs Back on the Policy Agenda?” In Urban Affairs: Back on the Policy Agenda, edited by Caroline Andrew, Katherine Graham, and Susan D. Phillips, 309–30. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Sonnen, Calr. 2008. The Macroeconomic Impacts of Spending and Level-of-Government Financing. A study by Informetrica Ltd. for the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, 10.

Stoney, Christopher, and Katherine Graham. 2009. “Federal-Municipal Relations in Canada: The Changing Organizational Landscape.” Canadian Public Administration, special issue, 52 (3), 371–94.

Ventin, Carla. 2005. “Government on Track to Deliver New Deal for Cities and Communities.” Accessed 21 November 2007, http://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/ip-pi/gas-essence_tax/newsnouvelles/2005/20050201ottawa_e.shtml.