The Long Memory

Crowded and noisy, the floor of the Large Council resembled the bustle of a marketplace more than a place of governance. Anticipation had brought out all of the council plus other notables. But one voice cut through the din of scraping chairs, shuffling paper, and chattering voices.

“The Long Memory is the most dangerous idea threatening our peace, prosperity, and security today!” Councilman Holt, a prominent and wealthy merchant, thundered at the crowd.

“Any reverence for the Long Memory, for the long done past, holds us back as a civilization! Those among us who call for this continued reverence are jeopardizing the security of our children’s future. We cannot be held hostage by memory. We cannot let memory keep us from forging our future. We owe this to our children. We owe this to our present, in which we see our peace, prosperity, and security threatened by bands of armed thugs in the north.”

Shouts of disagreement met this statement but were soon drowned out by the shouts of Holt’s supporters.

Among the dozen or so observers in the gallery sat Cy and her close friend Ban. They wore the dark green cloaks marking them as Memorials, keepers of the Long Memory. The very people Holt railed against. Cy and Ban were not full Memorials yet. They had yet to finish their final year of apprenticeship at the capital’s Central Library. There they learned to delve into streams of memories stretching far outside their lives. They were both apprenticed to the same elder, Hammon, considered to be one of the most skilled Memorials.

Ban sat, fidgety and impatient. She muttered under her breath a steady stream of expletives directed at Holt. Cy sat quite still, eyes fixed on the scene below.

Cy came to the Capital from the north as a nine-year-old after her family was killed in a battle in the foothills of the Coull Mountains. All of her family members were prominent regional Memorials. After the dust of the battle settled, Memorials from a nearby library searched for survivors. They found Cy holed up in a root cellar not far from her family’s now-decimated home. Cy was taken to the Central Library, where Hammon took her on as a pupil, and now as an apprentice. When Ban arrived from the Riverlands west of the Capital some nine years ago, it had been like gaining a sister in her and Hammon’s odd little family.

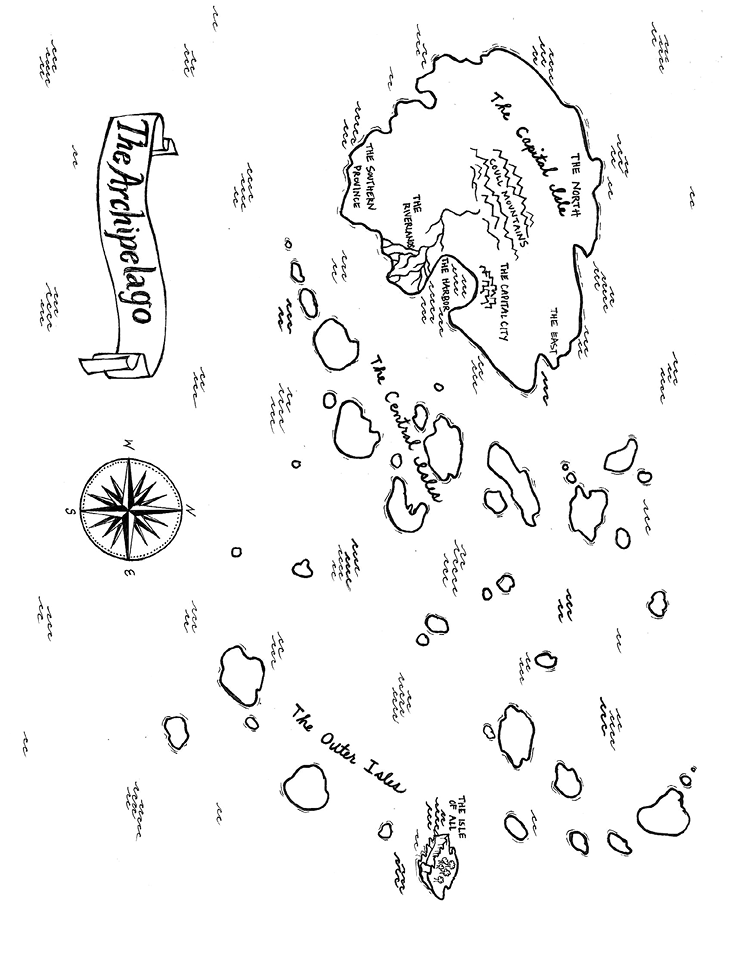

Cy examined Holt from her seat in the gallery. He was a large, bellowing man with muttonchops. His clothes always looked uncomfortably tight. In recent years, Holt had cast the status of the Memorials into debate. In times past, Memorials were positioned near power. The kings and queens of old kept Memorials near to guide them in their ruling. Memorials held positions of honor in towns and villages. From such places the Memorials had been instrumental in the rule of the Archipelago.

Over time, the royal houses diminished under the growing power of the merchant class. Kings and queens ceased to be meaningful rulers, and what had always been the Royal Court became the Large Council, from which all authority now came. But the reverence for memory remained. It was a part of the identity of the Archipelago that the record of the past should guide the governance of the present and the building of the future. Memorials, by law and custom, were part of any lawmaking, and approval of the Memorials was always required before actions such as mobilizing the provincial armies. Any new proclamation or law was sent to the libraries for review. This process frustrated a growing number of council members who saw it as slow, cumbersome, and unnecessary.

“The plodding methods of the Memorials hold us back as a civilization!” was a common refrain of Councilman Holt.

The resentment of the Memorials and their libraries reached a fevered pitch when the Central Library sent a proclamation back to the council. The council planned to mobilize all provincial armies to march on the north and quell rebellion and ethnic violence. The Memorials’ findings cautioned against acting in a region where much of the current situation was due to the past actions of the council itself, a historical fact the council seemed most eager to erase.

Among the most outraged, Holt traveled from province to province condemning the Memorials for holding back necessary action. He was adamant that the actions of past councils were inconsequential and not germane. Without the support of the Memorials, the council could not move forward. Holt had spent years leading a movement to weaken the rules granting the Memorials sway over the work of the council. As the violence in the north increased, fewer and fewer council members spoke out to challenge him. Then, six months ago, a band of Orm Mountain rebels had barricaded a northern provincial government hall and set it on fire, killing 120 people. Meanwhile, the Coullish were moving down from the mountains, sacking villages and seizing back ancestral lands.

Now the debate taking place on the council floor below Cy and Ban would rule on a proposal by Holt and his allies that called for the containment of what he called threats to the peace of the Archipelago. This included elimination of the role of Memorials in governance, strict regulation of libraries, and abolition of the registry of new Memorials. Holt used the recent deaths to push forth his proposal at Large Council, bypassing public debate.

Cy let out an impatient sigh. She knew Holt had many interests in the north, none of which had anything to do with the peace, prosperity, and security of the Archipelago.

Cy let her focus shift inward, letting the scene before her blur, blending from one image to another. New voices sounded and others went silent. Her body relaxed, her heart slowed. Her eyes took on a glassy, unfocused look, their pupils dilated to large dark pools. Such was the demeanor and practice of a Memorial shifting from the present to the channels of Long Memory.

A past memory overlaid the present—ghost images superimposed on flesh. Cy felt the weight of the memory, knew it hailed from before her birth. Older memories felt heavier, the pressure behind her eyes increasing the further she reached back. In the beginning Cy felt like she was being crushed from the inside out by any memory before her time. But after years of training, in her final year of apprenticeship, she barely noticed the weight of this memory.

The phantom voices of a long gone council rose and fell: “The settlement must take place. We can no longer allow the Northernlings to continue wandering across all the lands with their herds.”

“Yes, they claim all the lands their stock grazes on. They use too much given their size. That land is profitable and can be used for the benefit of all.”

The gold coins clinked together. Cy knew these were the voices of the merchants. They said they wanted the settlement project for the good of the Northernlings. The memory had the sharp taste of falsehood. The land of the north was rich and good for growing grain and raising herds of livestock. Many of the wealthier merchant houses saw the settlement project as a means to gain access to production of goods in the north.

A green-cloaked figure finally stepped forward to speak. “The Northernlings are not of one people but of many, many identities,” he said in a voice soft but firm. “The Northernlings of the mountains are not the same as those who roam the plains. They are the oldest people of this land, having been here before the boats of the Archipelago landed many of our ancestors on these shores. They are a proud and diverse people. We must seek a Memorial from the north to confer with before taking action.”

Cy felt the figure’s presence through the memory and knew it instantly. She had spent countless hours with this presence guiding her through the streams of memory—it was a much younger Hammon.

Cy would have known it was Hammon even if she had not felt his presence. In lessons at the Central Library, he had made reference to this memory often, a pivotal turning point in their history.

Ultimately, in what was one of the most divisive actions in the Archipelago’s history, a northern Memorial was not sought, and the settlement project was enacted. Many were uneasy with the move to act without a blessing from the Central Library. It also precipitated the decline in the stability of the north, bringing on more violence and poverty. Ever since the settlement project, the north had been mired in conflict, with no small role played by the various armies of the governing provincial houses. One house would arm one faction while another would arm another. The factions then fought each other and the provincial armies, and the north saw the rise of petty rulers fighting for what limited power they could hold.

Jumping at a sharp jab to the ribs, Cy was yanked back to the present, back into the council chambers.

“Get back here!” Ban hissed in her ear.

Cy’s pupils contracted and her face flushed as her heart sped up. Back in the present, Cy glanced around the gallery. A group of men sitting nearby looked at them with barely concealed contempt, while a cluster of women gave Cy and Ban uneasy glances. Looking down at the floor of the council, she sensed that there were far more speaking in support of Holt than in opposition. Cy stood sorrowfully, and left the gallery with Ban.

The air hung heavy from a recent rainstorm, the kind that frequented the coast. The humidity made the air fragrant with flowers and earth. Beneath a fig tree in the Central Library gardens Ban paced nervously, while Cy lay on the grass trying to stay cool.

Cy wore her thick dark hair long, as was the custom in the north for both men and women. She liked to lie on the grass, hair fanned out around her like a cape, the cool of the earth on her neck and scalp. In the heat and humidity of the Capital, Ban could never understand why Cy wouldn’t just cut it all off. For her part, Cy couldn’t understand how Ban could stand to be barefoot all the time. Coming from the Riverlands, Ban had grown up on boats and docks where most everyone went shoeless.

Ban flopped down at the base of the tree and began to eat one of the ripe figs.

“What will we do, Cy?”

Cy turned her head to look at her friend. “Prepare for the worst, I suppose. What else can we do?”

• • •

“She is a Coull and a Memorial,” said the paunchy, balding man standing in the middle of Holt’s chambers. “Her family were all Memorials, killed in some tribal dispute years back. She was at the hearing today, with another Memorial. She even had the audacity to use the Memory while you were speaking.”

Holt only grunted. He did not turn to look at the four others in his chamber. He stared at the window, not out at the rolling seas but rather at his reflection. He wanted to see himself in this moment of victory.

“Yes,” continued the speaker. “She is powerful, though—apprenticed to Hammon the elder.”

Holt interrupted, breaking his gaze at his own reflection. “I do not care about the old man. But the girl I would like removed.” He moved to sit in an armchair. “When we take the libraries, make sure you get the girl. Gather what men you need. Use plain blades, no house markings, and no uniforms. Take the libraries, starting with Central. Quickly. The momentum must be sustained. We can’t allow anything to go wrong, not when we are so close to victory.”

The men around Holt nodded acknowledgment and departed. The man who had spoken, Timmon, remained. Timmon had known Holt for years, watching and helping him build to this momentous achievement. Timmon could sense there was something more on Holt’s mind.

Holt poured two glasses of wine. “You know the legend of the binding, Timmon?”

“Of course. Doesn’t every child learn of it in school? It is the story of how the Long Memory was bound to a line of people charged with seeing our memories safeguarded.”

“Yes, the great story of the binding,” Holt spoke mockingly as he took a seat beside the closest person he had to a friend.

“Do you know, Timmon, in some circles it is said it was the Coullish who first told the story of the binding? I have been to the north many times and have heard the story of the binding told very differently than how we learned it in school. In the far north it is said that powerful story makers feared the loss of history, and they used the letters of the making found only on the scrolls in the caves of the Coull Mountains to write a story. A story that would bind memory to a line of people. The Memorials.”

Holt paused to sip his wine, and silence ensued. Timmon was unsure if he should speak, and he was about to when Holt finally continued.

“In Coull and other obscure parts of the north, it is also said that these story makers wrote a story of unbinding.”

“A story of the unbinding?” Timmon started. “I confess, I have no knowledge of such a thing.”

“I am not surprised. I believe it is even little known among the Northernlings themselves. And among the Memorials it is an esoteric study.”

“But would not the unbinding of memory be a means of reaching our end? To stamp out the Long Memory?” Timmon sat forward, looking at Holt.

Holt shook his head. “No, I think not. To unbind memory would be to free it. The Memorials are meddlesome, but they do serve a useful purpose in containing memory. Now the people remember only what they need to in order to go about their lives. To unbind memory would mean to restore full memory to all the people. It would mark our end. What we need only do is control memory through containing the Memorials.”

“This Coullish Memorial, you think she—” Timmon lifted his eyebrows.

“If the legend is true, I believe the story of the unbinding might be held somewhere within her endless memory. She comes from a strong line of Memorials and from the very lands of the binding. Indeed, had a Memorial been sought prior to the enacting of the Settlement Act, it would have very likely been her mother.”

“You have known of her for some time, then,” said Timmon.

“Oh yes. She may not know it. But we have history between us, she and I.”

• • •

Preparing for the worst does not make it hurt any less. Two days after the vote, they came to the library in the middle of the night. The smell of smoke woke Cy first. Within minutes, hands seized her in the dark and dragged her from bed. They thrust a burlap sack over her head, bound her hands behind her back. She heard shouting and the clanging of metal—the clash of swords.

It was hard to breathe under the sack. Her capturers half shoved, half dragged her. She stumbled and became entangled with the legs of one of the intruders. Both fell hard. A boot kicked her in the gut.

“Get up! Get up, damn you!”

Arms jerked Cy to her feet, and she struggled to stay alert, clinging to reality. It was no use. Feeling nauseated, she threw up and lost consciousness.

Over what seemed like days Cy flitted in and out of consciousness. She had been on a ship, that she knew. She had felt the rolling of the sea, the dampness and saltiness of sea travel. There had been bodies, many bodies, tightly packed in the hold below the ship’s deck. She remembered groans mixing with the creaking of the wooden hull. No one had cried out, though. Cy herself had kept silent as a tomb.

But now there was nothing. No bodies, no sounds. Cy felt cold, sore. She lay face down on a smooth stone floor. Lifting her head, Cy could see a wooden cot. With a heave, she lifted herself onto all fours and crawled toward the cot. Lights popped behind her eyes.

Now she raked her hands through her hair, felt the knots and dried vomit. Cy’s stomach clenched; she felt disgusting on top of broken. Cy slumped onto the cot and her face landed in something wet. It was a bowl of turnip stew beside a piece of flat bread and a small cup of water on a tray.

Cy cursed. Half the soup had spilled but the water cup was still full. She resisted the urge to down the water and the soup in a few gulps. Instead she sat and slowly sipped about a third of each, then waited to let it settle before downing another third.

The meals came twice a day, pushed through a slot in the cell door. Beyond their hands Cy saw nothing of her captors. After several days, she felt some strength and clarity return. She began to save a small amount of water from each meal until she had a full cup. Tearing a scrap from her tunic she dipped the cloth in the water, using it to clean her wounds and wash the filth from her body as best she could.

Cy scrubbed her toes and thought of Ban. She and Ban loved to go to the seawall in the Capital harbor to soak their feet in the cool water. Ban had grown up on boats. Her father owned a fleet of barges used to ship inland crops and other goods to the Capital. Cy hoped Ban had escaped the raid on the library and fled to her family’s home in the Riverlands. She could easily have found passage, smuggled upriver on one of her father’s ships if she had made it to the harbor.

“If Ban had been on the ship with me, I imagine she would have called out to me,” Cy thought. She smiled a little at this, thinking about how her friend, continuously chattering, could not have kept her mouth shut, not even if threatened with death.

The days were monotonous. Cy spent her time watching her bruises turn from deep purple to yellow until the day she finally felt strong enough to dive into the streams of the Long Memory so she could understand where she was being held. Images layered upon one another to form a sort of moving diorama of the fortresses’s history. Some were sharp and clear, some faded and blurred. All around her the memories of people imprinted in time. It was a cacophony of yells, sobs, and scraping of shackles. So many people had suffered here. Died here. It almost overwhelmed Cy. She swayed where she stood. With great effort, Cy cleared many of the memories, allowing those remaining to come into sharper focus. They confirmed Cy’s hunch about where she was being held. The eastern edge of the central Archipelago was dotted with dozens of small stone islands turned defensive outposts and then abandoned. Some of the forts had dreadful histories, places where refugees or slaves would be held without recourse, until they withered to dust.

Cy spent hours swimming through the channels of memory, for as long as she could stand. Some of these memories were so old that they pressed down on her, making it difficult to breathe. It took time, but she allowed the images to layer and fade until she could clearly distinguish one memory from another. In this clarity Cy could almost walk through the memories as she paced her cell. She listened to a mother sing a lullaby to her child, both fresh from a slaver’s ship. Cy sat in on a whispered conversation between ten former slaves turned captives. They huddled in the cell planning escape.

“The guards will have to open the door if they cannot open the slot for our food. We can be on either side of the door, ready.”

Cy stood and let the memory fade. The practice made her feel sad and drained. It was the exploration of the past, not merely the facts of history but the stories of the past, that made the Memorials so important. A Memorial did not simply know that this fortress had been used to cage refugees, a Memorial smelled the death in the air, heard the sound of screams, sensed hope draining from bodies like spilled blood. With Memorials remembering the pain and devastation, their role was to ensure that things like these prison forts would never be used again. But here was Cy sitting in this cell, drowning in the pain of the past mixed with her own.

The sound of her door being thrown open ripped Cy back from the Long Memory. Then three guards were upon her, wrestling a burlap sack over her head and shackles on her wrists. In the moment before the sack went over her head Cy saw her guards’ faces. Young, so young, she thought, and a little uncertain. Cy’s heart pounded.

The guards marched Cy out of her cell, up several short flights of stairs. Trying to contain racing thoughts of being thrown off a cliff into the sea, Cy struggled, but her guards just dragged her with more force. Cy began to panic. She was going to start screaming, she thought.

A door scraped open and fresh air brushed over Cy. In an instant someone yanked the sack off Cy’s head and shoved her forward. Hands still shackled, she landed hard, face down. Without a word, the guards uncuffed her and left, sealing a door behind them.

It took several minutes for Cy to gain her vision. She was in a tiny courtyard of sorts, completely surrounded by high stone walls. Gravel, grass, and some flowering bushes. Most welcome was the brilliant blue sky. Cy rolled onto her back, staring up at it.

After some time, the scraping of a door jarred her peace. Cy sat up quickly and looked around. Across the courtyard, a mere ten feet or so away, a slender man seemingly unfolded himself through a small wooden door. As he straightened, Cy saw that he carried a canvas bag and wore a broad woven hat. She moved to stand, and the man jumped at the sound of her body on gravel. He dropped the bag with a clatter, and an assortment of gardening tools spilled out. Taking a square of cloth from his back pocket, the man wiped his brow, cleared his throat, and bent down to collect his tools.

Cy watched cautiously. “Hello?”

The man finished picking up his tools with the air of a person focused on ignoring something obvious. He took up some clippers, setting to work on a hedge.

“Hello,” Cy said again.

The man’s clippers worked faster.

“My name is Cy. Are you the gardener here?”

The man stopped and wiped his brow again. “Yes, and they cannot be bothered to tell me when there will be someone here and when there will not be someone here, it seems. So please stay over there while I work.” A slight accent flavored his soft voice, almost covered by the nervous tremor.

“Of course,” she said, “I would not harm you. Please, do your work.”

The man worked meticulously and seemed to enjoy the challenge of making everything symmetrical. After a while, he packed up his tools and went to the door.

As he stepped through, he looked back at Cy. “My name is Makati.”

And so it began that every other day Cy would be removed from her cell, taken to this little courtyard and left for about an hour.

It was with no predictability that Makati worked in the courtyard. At first he would only acknowledge Cy with a nod. But over time and after many promptings, Makati began to respond. Mostly he would only answer questions about the garden. He told Cy the names of all its plants. Eventually he told Cy about the gardens in other parts of the fortress. Cy learned from Makati that there were about one hundred other prisoners. Makati said new prisoners arrived every now and then on ships, usually no more than two to three at a time.

One afternoon Cy sat in the shade of the wall and studied Makati as he worked. His deep red-brown skin was much darker than her own. It marked him as someone from the Outer Isles. He worked barefoot, dressed in plain linen pants and a soft woven shirt.

After a time, Makati asked, “You are a Memorial?”

Cy nodded yes and stretched her legs out in front of her.

“Is that special?”

“I don’t know. Some people certainly think so.”

“It wasn’t until I reached the west that I heard of Memorials,” Makati said, continuing to weed. “Where I am from, on the Island of All in the Outer Isles, we do not have Memorials. We used to have what we called Holders. Those raised to be keepers of the stories that made us. But they passed from existence some time ago.”

Cy, curiosity peaked, asked, “How is it that the Holders stopped being?”

“Oh, it was many years ago now. Long before my day of birth. It is an old story.” Makati sat back on his heels.

“The story says the Holders’ tongues became heavy and clumsy. They couldn’t tell the stories anymore without mixing up the details. The people thought the Holders were going mad; some thought a great illness had come. The Holders themselves became frustrated and angry. Some threw themselves from the cliffs into the ocean. Others sank into general village life to become herders or farmers. My family once had a strong line of Holders.”

“What happened to the stories?”

“Oh, well, we have stories—legends and tales that mostly serve to warn the young to not act rashly, or to scold the unscrupulous trader. But very little is told anymore of the making of All. My people are very absentminded, it would seem. We forget so easily! Everyone in the Outer Isles knows this about All.” Makati chuckled. “But they are no better, I can tell you that.”

Makati stood with his canvas bag of tools, his hand above his eyes to shield them from the sun. “I am done now and must be going. It was good to talk to you.”

Cy smiled. “Thank you for the story, Makati.”

Back in her cell, Cy wondered at Makati’s story. It had made her think of the story of the binding. She hummed a short tune as she fingered the frayed hem of her tunic. The tune was that of an old verse, one she and the other children would shout during a game of chase. It took a few minutes before Cy remembered all the words:

Papa yelled, Do you know what you did?

No Papa, no memories do we hold.

Mamma scolds, Do as you’re told!

We children run, we don’t know what we’re told

For we have no memories of our own

The Memorial took them all to hold.

She ran through the little song a few times before letting out a laugh. “Well, that certainly does take on a new meaning now,” she said aloud, thinking of Makati’s story.

The object of the chase game was to pull little pieces of colored cloth from the waists of other children. The idea was that the cloth scraps were memories a Memorial had taken, and without the memories the children would always be in trouble with their parents for forgetting what they were told.

Cy thought of Makati and his story from the Isle of All. How could it be that the Holders of All had lost their stories? Why was it that on All there were no Memorials? It was troubling to Cy that on All, and perhaps elsewhere in the Outer Isles, the people would have no way to recall the stories of their own making. Cy whispered the last line of the rhyme, “The Memorial took them all to hold.”

Cy lay back on her cot. The binding did not stop the people from remembering things on their own, of course. She certainly remembered things from her past. But without the collective memories of the Memorials, the past was utterly lost. Cy wondered if the stories of All could be found in the Long Memory. If so, what did it mean that she could find them but not the people of All, the people they rightly belonged to?

Had other places lost their memories and stories as well? Not in the north. The whole of the uprising was based on remembering past wrongs. Cy paused. Or was it? Were the people truly remembering or were they just reacting to immediate wrongs, based on which house armed them? Cy thought of the settlement project, the fighting in the north, Holt’s most recent actions against the Long Memory. The Memorials were powerless to stop this repression from happening against themselves and their own, and the people did not rally to the cause. Some complained, muttered angrily against the actions of the council, but there was no fire behind their words. None outside the Memorials seemed called to action.

“Where are the people in all of this? Why do they stand by and let this happen?” Cy remembered Ban saying as Ban had stomped around their favorite fig tree in the Central Library garden. Her friend had received a letter from her father saying that the Riverland shipping guild would not cease transporting Holt’s goods. Ban lobbied her father, vice chair of the guild, for months, but it was to no avail.

“It’s like everyone has forgotten how important the binding was, how momentous. It is meant to protect and safeguard the Archipelago. But they allow it to be stripped away and replaced with Holt’s preposterous Act for the Containment of Threats to the Archipelago.”

At the time, Cy had laughed at the mocking tone in Ban’s voice as she spoke of Holt’s act. But now, in light of Makati’s story and her own capture, Cy now saw nothing amusing. In fact, a creeping realization began to fill her. The people don’t remember the importance of the binding. It is not their memory.

“The Memorial took them all to hold,” she whispered.

Cy shifted on the cot, covered her eyes with an arm for a moment. Then a sharp rap on her cell door startled her, and a harsh voice shouted, “Prisoner, clear away from the door!”

A guard entered, followed by three others dressed in uniforms of the Provincial army. Moving quickly toward Cy, they lifted her, and before the familiar burlap sack came down around her head Cy saw the crest of House Holt embroidered the soldiers’ coats. Cy’s heart pounded.

Out of the cell, the guards went left instead of the usual right to the courtyard. After ascending several flights of stairs, her guards pushed Cy roughly into a room, forced her to sit. She heard an ominous click as cold metal touched her wrists.

A moment later, light flooded her vision. The room came into focus in bits and pieces. Walls of large stone like the rest of the prison, but the floor of this room was a deep polished amber wood. She sat on a small wooden stool at a large table, hands shackled together and chained to the floor. Across from her sat another person—it was Councilman Holt himself.

“Do you know how long you have been here in this castle, Cy?”

“This prison, you mean?” Cy met Holt’s eyes.

Holt pursed his lips. “Four months.”

Cy spoke again, fear making her mouth dry. “After all these months, I cannot imagine what there could be between us that needs discussing.”

“What is between us?” Holt gave a snort. “Your existence! That is what remains between us. Your existence and that of the other Memorials held here.”

“Held here?” Anything to avoid the word imprisoned, thought Cy.

“The war in the north moves apace,” he continued. “The people are aligned with this progress. But so long as you and the others are here—”

Holt stood and moved toward an open window. “Well, then there is always the threat of the question Why?”

“You fear the people remembering,” Cy said. She tried to make Holt look at her, but his eyes would not leave his view out the window. “That they will remember you took me and the others away. That you killed many and burned the libraries, and they will ask why. And you will have to answer.”

“Oh, shut up!” Holt snapped, finally stepping away from the window. “Only the nostalgic will truly question your absence and care. The Long Memory fades, and soon enough memories will be what they should be—myth and legend.”

“You cannot render memory powerless, Holt,” Cy said. “You could round up each and every Memorial in the Archipelago and let us rot in these cells. You could ensure that each newly born Memorial never has their skill fostered. In that you could most definitely end our line. But you will not eradicate memory.”

Even as she said it, though, Cy wondered about the Isle of All and doubted.

The binding, Makati’s story, her own memories—it all meant something.

Whispering to herself, Cy mused, “A people who remember will not be exploited again. A people who remember will take action.”

A horrible realization began to take form in Cy’s mind. People were not remembering. They could not remember those things of the past that shape the present.

“Memories are supposed to be shared. It is what gives them power.” She said this loudly, though it was directed as much to herself as to Holt. “Perhaps it is time the people remember for themselves.”

Cy looked directly at Holt.

Holt peered back at Cy, leaning closer. “What?” He forced the question through gritted teeth.

“Do your worst, Holt. But without the Memorials, memories will have to go somewhere. Each person holds her own memory of what she has lived through and seen. You cannot take that or destroy that, for it is human.”

Holt’s face purpled. In a few strides he rounded the table and then drew a short sword from his belt. He yanked Cy’s head, exposing her neck. Cy’s heart beat erratically and her face flushed. Her eyes traveled down to the blade and its hilt, on which the crest of House Holt was inlaid in gold. In an instant Cy wasn’t in the room with Holt. She was far away in a moment of her past life, lying on hard-packed dirt, screaming as a man pulled her away from the prone dead body of her father. There was a flash of swords, one very nearly cutting Cy in the stomach. In this long-buried memory, Cy saw the glint of light off the hilt, the flash of a crest.

Just as suddenly Cy was back in the room with Holt. With the sword at her throat, Cy’s chest heaved. She felt bile rising in her throat and thought she would be sick. Why had she not been able to put it together before now? The memory of the council hearing, the one she had always struggled to see through. She always lost it as Holt rose to speak, under his house crest.

“It was you,” she gasped. “Your armies killed my people. It was House Holt.”

Cy strained forward, pulling on her restraints.

“Oh, ho! She remembers. She remembers what truly remains between us.” Holt smiled wickedly.

Cy struggled hard against her shackles. She wanted to leap at Holt. To hurt and maim him. Cy could only see the crest, and it filled her with a panic and rage she had never known.

Cy screamed, “I don’t need the Long Memory to know what you and your wealth have done to my people! I lived it! Others will remember too!”

Holt struck Cy across the cheek with the hilt of his sword, knocking her to the floor. “Your people are weak!” he spat. “They remember nothing of who they once were. Only that they are now lawless barbarians.”

He commanded his guards: “Remove her!” Then he stood with his back to Cy as she was hoisted up, dazed from the blow. “As a Memorial, Cy, you should know it is easier to control what people do with their memories than one might think.”

• • •

Several days later Cy was given time outside in the small courtyard. She was anxious since her meeting with Holt, sensing that his anger would have repercussions. She had formulated a plan, and when Makati came to garden, Cy wasted no time.

“Makati.”

His eyes grew wide as they fell on the large and swollen bruise on Cy’s cheek.

“I need a favor. I do not think I will be given time outside again. I am sorry to have to ask. I do not wish to risk your safety or overstep any bounds of our friendship, but I need this from you.”

Nodding, Makati stood up straight. “What do you need?”

“I need you to send a message for me, to the west. To the Riverlands.”

Cy chewed her lip. This next favor carried more risk. “I also need some way to send a message among the other prisoners. Makati, do you . . . are you friendly with any of the guards or the cooks?”

Makati stammered for a moment. “A letter to the Capitol Isle I can send. I have a friend I write to sometimes. It will not look suspicious. But to communicate with the other prisoners?”

“A few days back, I was taken to Holt. He is angry and I fear he has plans. If I can get word to a friend in the Riverlands, I think the other prisoners and I can at least buy some time until—” Cy broke off, frustrated. She could only hope Ban was in the Riverlands.

“I know a few of the guards. We play cards together. They too are from the Outer Isles. And, like me, many of them do not agree with what is being done here. I can ask.” Makati trailed off nervously.

Cy reached out and held Makati’s shoulders. “Friend. Thank you!”

“I have some paper here. I can take the message and leave you with the rest and with my pencil.”

Cy quickly wrote the note to Ban telling her friend where she was and what she planned.

Then Cy wrote a message on the other piece of paper:

My name is Cy. I am a prisoner here also. I believe Holt means to act soon. There is an old tradition among the Archipelago: in a conflict, wronged people will plant themselves outside of the home of the aggressor and refuse to eat until the other agrees to share a meal. It has been used in this very fortress a very long time ago. I am sure you have seen it in the Long Memory. I am sending word outside to trusted Memorials. They will ensure the people know. Would others join a hunger strike?

Cy handed Makati the bit of paper. He did not read it but rolled it up and placed it in his gardening bag.

“Thank you, Makati,” Cy said, her voice heavy with emotion.

Makati nodded and left through the small door.

Cy was right in predicting that her trips to the courtyard would end. Five days went by during which she had not been taken out once. She paced her cell, her new daily routine, waiting for food.

Then one day, when her first meal of the day arrived, there was a small message tucked under her bowl, scribbled in haste on the same piece of paper as her original:

My name is Je, I am an Easternling from a library on the coast. I have already started refusing my meals. This tradition you write of is particularly strong amongst my people. If enough of us went on hunger strike and if you can truly get word to the outside then we could pose a challenge to Holt.

Cy ignored her meal and just sat holding the note. She felt a tingling in her fingers. That undeniable feeling of something big beginning. Cy wrote back and left the note in the same spot under her bowl. She had to trust that, however the note had made it to her, it would make it back.

In time a reply arrived but not from just Je. Notes from other captive Memorials crowded the paper, creating a conversation. All supported a hunger strike. Cy got down on her belly and squeezed under the cot. There she pried loose a small stone behind which she had stowed Makati’s pencil. Retracting it and pulling herself out from under the cot, Cy bent over and began to write. She was hardly able to contain her anxious excitement:

There are nearly one hundred of us being held here. Eighty of us on hunger strike would be enough. When you receive this note, mark your name and find a way to pass it to another Memorial.

Cy also retrieved a small square of paper from under her mattress and wrote a letter to Ban explaining more of the emerging plan.

That night, Cy sat at the door waiting for the guard to arrive to take her untouched bowl and plate. It was risky, she knew, but she had to make sure the guard knew to get the message to Makati.

Cy sat so long that she fell asleep, but she awoke with a start when the guard came. She pressed the notes into the guard’s hand.

“Please, Makati needs to get this.”

The guard recoiled, but after a moment he took the papers.

• • •

One week later Cy’s door was thrown open by four soldiers, not guards, who grabbed Cy and dragged her down a corridor. She heard the shouts of more soldiers, the sound of others being taken out of their cells. All Cy could think was that the day of execution had finally come. Perhaps Holt had intercepted the letters. She thought of Makati, and a panic built in her like that she felt the first time she was taken to the courtyard. An acrid bile taste filled her mouth. She fervently hoped Makati’s part in this remained undiscovered. Her stomach clenched and her heart raced. Then she felt gravel beneath her feet and blinding sun above.

A soldier shoved Cy, and she hit the ground hard. Around her, others were made to kneel.

He means to execute us all at once, Cy thought, fear flowing wildly.

But after a time all went quiet, and nothing more happened. They had all just been left kneeling in the hot sun. At first perplexing, it became torturous. With the burlap sacks over their heads, the bound Memorials were suffocating. Cy’s knees went numb. She sucked in air, but it was devoid of oxygen. Her head swam, and she thought she would vomit.

Hours passed. At the brink of losing consciousness, Cy finally heard footsteps and then a great commotion as soldiers yelled at everyone to get up. She stumbled, then was accosted and dragged back inside to her cell.

No message came with the meager evening meal. Cy could not imagine eating anyway, and just sipped the water. Thirst burned her throat. Her head ached. Once the water was gone she lay on the cool stone floor and fell asleep.

This became the everyday routine: pulled from her cell with others and dragged outside midday, then hours spent hooded and kneeling in the hot sun. Cy felt her strength waning both physically and mentally as weeks dragged on. The few times Cy tried to reach the Long Memory she nearly passed out. This more than anything made hope seem fleeting.

Some weeks into this torture, they knelt in the yard one day not baked by sun but soaked by rain. Not a refreshing rain but a thick soup. Unless Cy kept her head bowed, the burlap over her head stuck to her mouth, suffocating her even more. Cy was so fixated on how sore her neck and shoulders felt in this position that she almost cried out in surprise when she felt the shackled hands of the person to her left nudging her own hands. Then she felt a small roll of paper between fingers. Cy carefully accepted the scroll and held it so tightly that her nails dug painfully into her palms.

Back in her cell Cy lay on the floor. She was so tired, so thirsty. Her body ached all over and she felt hot, unable to cool off even on the cold stone floor. Slowly she unclenched her hand, fingers stiff, to pluck out the note.

It consisted of all the past notes and a collection of names. Some she recognized from the Central Library. Others were unknown to her. Seeing so many names, Cy suddenly felt much less alone. She counted the names and then counted again. Eighty-six.

Cy retrieved the larger square of paper Makati had left her with. She tore off a small piece and wrote a note to Ban, copying the names of all the Memorial hunger strikers. She beseeched her friend, “Compel the free Memorials and anyone sympathetic to our plight to honor the tradition we invoke and to think of us who are locked away for the crime of remembering.”

• • •

“Search the cells!” Holt thundered. “Confiscate anything that could be used for writing! We have to cut them off from the world!” His hands gripped a dozen or so posters brought to him by Timmon.

Timmon had found the posters at a Riverlands inn, but they quickly spread all over the Eastern Isles. Sailors had left them, the innkeeper said. The names of each of the captive Memorials blazed in commanding letters. Underneath were excerpts from their letters. The posters gave information about the hunger strike and a plea that those on the outside take immediate action.

The people were taking notice of these posters. Rumbles of rebellion met Holt across the Archipelago, and what had been irritating setbacks grew into outright challenges to his authority. It was in the east that the most discontent brewed. Holt had needed to find a new way to transport weapons and goods to the north after his caravans were barred from the eastern road by one town council. He had tried to turn to the rivers for transport, but could not find enough captains and barges to carry his goods. In fact, the seas seemed to carry defiance faster. The hunger strike served as a beacon, uniting resistance in all parts of the land.

“Guards!” Holt bellowed from his office. “Are the prisoners in the yard?”

“Sir, yes, Master Holt. They were brought out two hours ago.”

In the yard Holt saw rows of kneeling prisoners, a hundred in all. Each nearly identical in ragged clothes and burlap hoods.

When the soldiers saw Holt, they snapped to attention. The most senior among them came to Holt’s side.

“Master Holt, this is a surprise.”

Cy’s stomach clenched. He was here. He must know of the letters.

Holt stood before the kneeling Memorials. “You think it matters to people if you all starve to death?” he bellowed. “It does not matter! No one cares that you starve and no one expects me to share a meal with you as some sort of pathetic penance.”

Despite her fear, excitement coursed through Cy. This meant their letters had been received! And he wouldn’t be here in such a rage if they hadn’t been effective.

“I tell you now,” Holt continued, “Give up this hunger strike and perhaps in time you will gain your freedom.”

The initial responding silence was shattered by a shout. “Freedom will come from death before it comes at your hands, Holt!”

This shout unleashed a torrent of agreement, and the Memorials cursed Holt.

“Who said that?” Holt stomped across the gravel.

Cy heard a grunt, sounds of a struggle. Holt was pulling a hood off a head.

“You are Je from the East. You started this, did you not? You were the first to stop eating!”

Cy then heard the sound of spitting. Holt’s scream of fury confirmed that Je had spit in his face.

“Kill her!”

Cy struggled up and pulled at her shackles. Adrenalin overcame thought and understanding. She just wanted to stop what was happening. But her efforts were fruitless, and after a few moments there was no sound of struggle. Perhaps Je was unconscious or maybe she just would not give Holt the satisfaction of seeing her afraid.

Back in her cell, Cy lay in utter exhaustion. Tears coursed down her cheeks, tears of sadness and horror at Je’s death. But also tears of relief. She knew that the letters were getting out and people were acting enough to threaten Holt’s power. No future was certain, but that was all right. Cy felt confident that the unbinding was upon the world, being shared by the many, as memories should be.