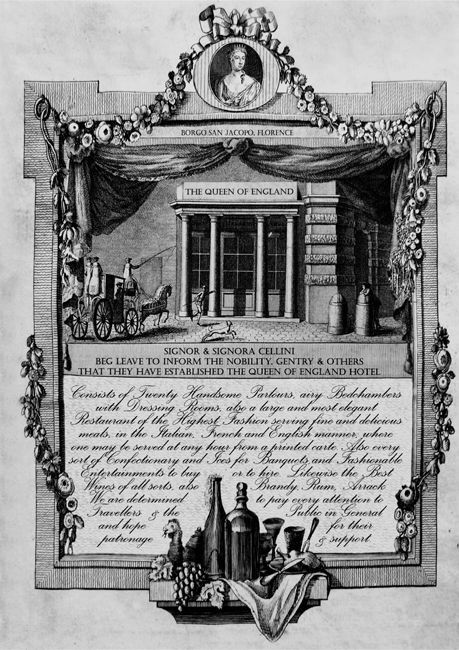

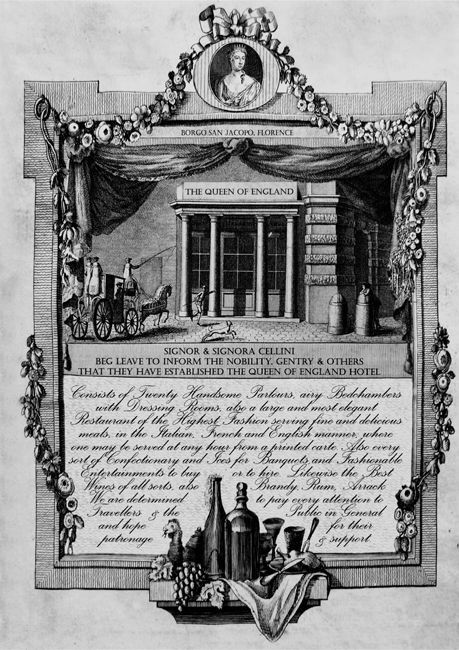

The Queen of England, Florence

Being Advent to Christmastide, 1777

Signora Bibiana Cellini, her journal

It began last year when the Earl of Mulreay and his mistress came back to lodge with us. The old fellow had just arrived in the city from the waters at Spa, his wrinkles powdered to the colour of decay, the outmoded patch stuck to his rouged cheeks.

‘My dearest Mrs Cellini.’ His touch was as dry as old hair papers as he lifted my hand to his puckered lips. At times he reminds me of old Count Carlo, but the earl would no more eat a viper than an oyster out of season. I had heard Count Carlo had snared some other heiress, poor creature.

‘My Lord, have you seen our new menu?’

As we discussed each new dish I noticed the pretty aventuressa at his side appraising my costume. That was also new from Paris, a Polonaise gown in broad blue stripes, the skirts hitched up in milkmaid fashion.

‘We have a Tiber sturgeon just fresh from the boat. Or a white Tuscan peacock. Or of course, if you care for something more homely, I have a taffety tart of quince and apples just baked.’

His grin showed the toffee-coloured stumps of the dedicated epicure. ‘A taffety tart?’ Clapping the silk-breeched spindle of his leg he smiled like an orphan promised a sugarplum. ‘Bring us what you surmise your best, Mrs Cellini. And the taffety tart with – custard if you have it.’

I was standing half-hid behind a marble pillar watching my serving maid clear the earl’s plates, when I heard him speak a name that knocked the breath from me like a cudgel. Without waiting to consider, I bustled over to the earl’s table.

‘Pray forgive me My Lord,’ I said with my sweetest smile, ‘but the name Tyrone just floated across the air to me. I know the man. Indeed, I owe him a debt of favour. I wonder, perhaps, if it is the same fellow?’

I donned a mask of simplicity as the earl told his tale. The English Braggadocio had arrived in Florence and reckoned himself a first-rate calculator at the gaming tables – but the local nobles had bled him dry. All I heard confirmed that this dupe was Kitt Tyrone.

‘Yet to think of what I owe that gentleman,’ I said, as plaintively as if I trod the boards of Drury Lane. ‘Do you know how I might find him?’

A liver-spotted hand patted my arm. ‘He lodges near the Coco Theatre. God will allow you to perform your good deed, only let the gambling fever abate, Mrs Cellini. He is a sick man. A little ready cash now would only agitate his brain.’

* * *

I retreated to my dressing chamber, but could not sit still. Kitt himself, and here in Florence. Unhappily, I recounted that he had followed his sister to Italy, and even more remorsefully, that his failure to discover her fate was my own doing. Yet why did the fool linger here? Oh Kitt, I beseeched out loud, catching sight of my vexed face in the looking glass. Damn him, I knew he was foolish and weak. God alone knew why, but I had to see him.

I gave myself no time to alter my course, only fretted that such an errand would enrage my husband. He might try to prevent me, might even suspect I was meeting a lover. So I will go in secret, I decided, for silence is best. Next I set on the idea of wearing an ugly black veil such as the local donne wear. The very next day while Renzo was out in the city I crept quickly out of a small gate at the back of the Hotel. In a black gown that matched my veil and plain leather slippers, I flattered myself I would pass for any modest Florentine lady.

The alley by the theatre was a dripping tunnel, stinking of ordure. I had to ask the whereabouts of the Inglese gentleman, of course. Finally, an old woman pointed a bony finger up a set of stone stairs. I knocked at the door, got no answer, and slowly pushed it open.

Even through the lace mist of my veil I could see the room was of the poorest sort: a stained pallet flung on the cold floor, a window patched with paper. Then I saw empty bottles of raw spirit. And in their midst, as drunk as a tinker, lay the twisted body of Kitt Tyrone.

Pressing my veil to my nose I sank down on a crooked stool beside him and touched his arm. ‘Signore,’ I murmured. ‘Wake up, Signor Tyrone.’

His eyelids rolled and finally opened.

‘Who are you?’ he croaked. I feared I must look like the angel of death in my pall of black lace.

‘A friend,’ I said, in a muffled tone.

He would not look at me, but seemed to be in a delirium, seeking points on the ceiling and walls. Then pulling the stained sheet over his shoulder, he rolled onto his side and blinked at the wall.

‘I am a friend,’ I urged. ‘An English woman who wishes to help you.’

Still he faced the wall, where the marks of vanquished bedbugs made a grim design.

‘Leave me be,’ he groaned.

I sat awhile, confounded. Beneath the sweet fumes of liquor he smelled of sickness, the rotten stink of a truly ailing man. I decided I must take command.

‘Signor Tyrone,’ I said severely. ‘You must come with me to a clean house and be nursed.’

Still he did not lift his eyes from his stupor. Vexed, I decided to surprise him by showing my face. If he knew me, I told myself, he would come to his senses. I threw back my veil, and for a moment was choked by the unwholesome air. Then I stood above him, my countenance open to his gaze.

But it was I who was destined to see how things truly were. His face was as pallid as wax in a tangle of wild hair, yet it was still Kitt’s face that I knew so well. Beneath the startings of a rough beard were his cupid’s lips, and though much sunk, the bones of his face still seemed handsome to me.

Then my vision shifted. It was his eyes that terrified me. I leaned over him, my face as clear as day, that face he had once called pretty. But his eyes still rolled and blinked without a sign of knowing me at all. Poor Kitt, for all my black disguise, was blind.

* * *

It was a terrible task to tell my husband about Kitt. When he returned that night from a banquet he had overseen, it was two hours past midnight. As Renzo undressed I told him of the tragic fall of my mistress’s brother, and his mouth hardened into obstinate silence. Finally, he splashed his weary face with water and sat heavily on the edge of our bed.

‘Are you trying to shame me?’ he asked with a fast hiss of anger. ‘A Florentine wife would never go to a man’s house alone.’

It is true that Italian women do carry a heavy yoke of old-fangled rules. So I made myself very sorry indeed, pleading ignorance, and swearing I was merely trying to do good.

‘It was an act of charity,’ I urged. ‘He is a stranger in the city, attacked by sharpers and somehow grown blind.’

Renzo sighed. ‘It is wood alcohol that has blinded him. He should have known better.’ But when I reached to throw my arms about his neck he jerked away out of reach. ‘As should you,’ he whispered, bitter with hurt. Suddenly I no longer knew where to place my hands. For so long they had found welcome peace around Renzo’s broad shoulders.

‘So tell me,’ he added, his voice steely. ‘When was this man your lover?’

I closed my eyes and allowed myself a silent hurrah of gratitude. Thanks to God I could tell the truth. Looking deep into Renzo’s hurt gaze I said, ‘He never was my lover. Think of it. You know that.’

With a grunt of agreement, he nodded. Then looking much like our little son Giacomo, Renzo scowled at the disobliging nature of the world.

‘There are hospitals. If you send him there you will have done your Christian duty.’

It was true. Yet to think of poor Kitt dying alone in a foreign hospital – I could not bear it.

‘No. He must come here. We have rooms. And God forgive me, but he will not be our guest for long.’

‘Why, in the devil’s name are you doing this?’

I scarcely understood it myself. It was a cold passion that drove me, refusing to be crossed.

‘Guilt,’ I said, suddenly looking away.

‘In Florence we say “Guilt is a gorgeous girl but nobody wants her.” Or in your case, perhaps a handsome man. Forget him. You will not be the first woman to shun her past.’

‘I may never have another chance,’ I said, and my voice cracked. ‘He is blind. He is dying. We led him to Italy and it has cursed him. While for me it has been a blessing, for I have all this bounty, our children, and mostly you, Renzo.’ I let my face fall on his shoulder. ‘Let me pay a little back,’ I whispered.

We sat entwined, each in our own thoughts for a long time, growing cold as dawn approached. As I pressed my eyes against my husband’s solid shoulder I saw Carinna dead before me, laid on that white bed, her pale eyes as lifeless as glass. All my chasing of bustle and happiness seemed only flimsy shrouds laid over the horror of her wretched corpse. At last Renzo patted my hair.

‘Come to bed. Yet I still do not see why we should have him,’ he said. The fight had left his body.

‘Because he is Evelina’s uncle,’ I said, and Renzo sighed, and I came to bed.

* * *

No one must believe that by taking in Kitt I felt any less for my husband. Renzo is my true love, the father of my beloved children. And thanks to him I run a great trade, and cook as I never could have done, back in England. Kitt is a different draught altogether. I know well enough now, that Kitt would have filled my life with despair. Yet the hours we shared in Paris do burn with a secret glamour in the calendar of my days.

Next day Kitt was moved into one of the hotel’s rooms, and by dinner time he slept in a bed of fresh linen, the gauze drapes guarding his wretched eyes from the winter sun. I hired a gentle nurse, Francesca, and she sat sewing at his side. That evening I fed him myself, setting his pillows behind his back and dabbing his lips with a snow-white cloth. Alone, I studied his ravaged face.

‘You need a barber,’ I said. I held my fingers above the dark shadow of his cheek, but did not permit myself to touch him.

‘Lady,’ he said quietly, his eyes seeming to search for me but not find me, ‘I need for nothing. Thank you.’ His fingers suddenly grasped the bunched silk of my skirt. ‘Am I in heaven?’

‘No,’ I laughed. ‘You are in the Queen of England Hotel, Florence. With friends.’ I patted his hand and loosened his pincer grip. ‘Now sleep,’ I murmured, standing to go.

Again he reached for my skirts but I had stepped away. ‘I am afraid to sleep,’ he groaned, looking about himself, but seeing nothing. ‘For where will I wake?’

‘You will wake here. The nurse will sleep beside you on a couch. You are quite safe.’

As I left he cried out as Renzo’s dog came running to greet me at the door.

‘Lady! I beg you, shut the door. Listen! Don’t let it come inside.’

‘It is only my husband’s hound.’

Ugo scratched and whimpered at the door and poor Kitt recoiled.

‘Great god has it followed me here?’ he wailed.

I spoke to the nurse of his fear of the dog, and we agreed that his blindness must have given him an odd terror, for perhaps some wild dog had once found him alone. It was only a long while later that I remembered Bengo and got to wondering what Kitt had found at the villa.

* * *

He was with us only a week before he unmasked me. It was almost Christmas, and Renzo was preparing all the delicacies Florentines must eat at the festival: roast eels, goose, fancy cakes with marzipan frills, and a kind of minced pie they call Torta di Lasagna, stuffed with meats and raisins and nuts. As his nurse Francesca had leave to attend mass, it was I who was bathing Kitt’s face one day with a cloth dipped in rosewater. By then I could look at his face without being overcome by miserable tenderness. His eyes were closed and his face was as sallow as parchment. I sighed more loudly than I should have, and pushed back a lock of his long black hair.

‘That perfume. Is it you?’ he asked. ‘Not the nurse?’

Warily, I replied, ‘It is Signora Cellini. The lady who found you.’

A wry smile tightened his lips. ‘Is that the same lady who cried out last night when the loaves were burned that there “were nowt left to serve the guests”?’

My heart thumped as I listened to the movements in the house: the banging from the kitchen, the children chanting from the schoolroom.

‘It is you. Isn’t it, Biddy?’

His thin hand grasped mine, the veins like knotted blue string on a stretched fan of bone. For some while we continued in silence, clasping hands like innocent children. Then, in a low tone, I told him how I was sorry not to have found him sooner. ‘It was good fortune you came here to Florence where I live.’

‘For once in my life I was lucky.’ His face grew clouded. ‘For you did not wait for me at the villa, did you?’ His grip was still tight around my palm. ‘It was you who left me the jewel?’

‘It was your sister’s wish,’ I whispered.

‘Now tell me the truth,’ he said, ‘what happened to Carinna?’

I had little time left before Francesca returned, so I rapidly told him all I dared. How to hide her great belly Carinna had ordered me to act her character.

‘Carinna was with child?’ He looked suddenly bereft. ‘Poor sis. And you Biddy, I thought you had changed much. Yet you always were sharp, I can see why Carinna used you. But what happened? I heard once that my uncle sent a man over to the villa, but there was no sign of her, or any of you. Is it true she left with a secret lover?’

‘She died in childbed,’ I said. ‘Kitt, it was a terrible lying in. As for the child’s father, he never came to claim her or the child. And to be so far from home—’ But for pity’s sake I did not tell the entire truth. That Mr Pars had fallen out with her as plotting thieves will, and she had died a poor suffering girl, with only us lackeys about her, and one of those her murderer. For the sake of her memory, I was too ashamed to tell him.

‘Where is she buried?’ Poor Kitt looked grey with pain.

‘In the graveyard at Ombrosa. Oh Kitt, I am sorry to say the headstone bears my name.’ I bit my lip as I saw his blind eyes move in agitation. ‘To those who knew us, I was Lady Carinna. I am sorry.’

He turned his head away. ‘And then you went on and prospered. Yet what does it matter?’ His fingers loosed in mine. ‘The dead child. Was it a girl or boy?’

At last I could cheer him. ‘No, no. The child lives. It is a girl. I could not part from her. She is my daughter, Evelina.’

He turned his face back towards mine. ‘What d’you say? Carinna’s child is here?’

‘Yes,’ I whispered, for I feared his raising his voice. ‘Only be quiet. My husband Renzo does not want you here. As for Evelina, she does not know you are her uncle.’

‘I don’t care who she thinks I am. Only bring her to me. Just once.’ He clawed towards my sleeve. ‘Biddy, you will do it?’

It seemed a small gift to give.

‘I will bring her tomorrow.’