CHAPTER 6

LOWER BROADWAY— VESEY TO CHAMBERS. THE CIVIC CENTER

The Woolworth Building

Cathedral of Commerce

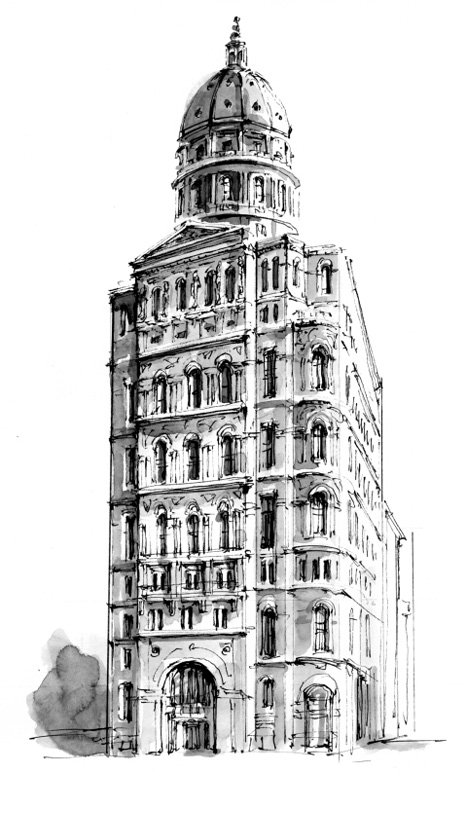

The fantastical, neo-Gothic WOOLWORTH BUILDING at 233 Broadway is the most romantic and beautiful building in New York. It was the masterpiece of CASS GILBERT (who built the U.S. Custom House) for the head offices of store owner F. W. Woolworth. The story goes that Woolworth was once refused a mortgage by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and so he told Cass Gilbert that he would pay in cash for Gilbert to build him the tallest building in the world, thus robbing the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company headquarters of that accolade. It cost Woolworth a cool $13.5 million, most of which was for the land.

The lower half of the Woolworth Building matches the height of another tallest building, the Park Row Building across the street, while the tower section above reaches a height of 792 ft (241 m), outstripping the Met Life Tower by 92 ft (28 m). The facade is faced with white terra-cotta, much of it replaced with stone in the 1970s, and adorned with gargoyles, fanciful ornamentation, and narrow, precarious-looking stone balconies, the view from which must be both precipitous and exhilarating. There was originally an observation deck on the 58th floor, but this was closed in 1945.

The Woolworth Building is reminiscent of the great Gothic churches of Europe, and during the opening ceremony in 1913, S. Parkes Cadman, minister of the Central Congregational Church in Brooklyn, described it as the “Cathedral of Commerce.” British prime minister Arthur Balfour said of the Woolworth Building, “What shall I say of a city that builds the most beautiful cathedral in the world and calls it an office building?”

Woolworth’s offices only occupied a couple of floors, while the rest of the building was rented out to some 1,000 tenants, whose rent presumably helped Woolworth to recoup the cost of the enterprise—although he claimed that the advertising potential of such an eye-catching headquarters meant that the building more than paid for itself.

The magnificent, grandly stepped lobby of the Woolworth Building is not unlike a church crossing, with vaulted ceilings covered in colorful mosaics. Looking down from on high are humorous plaster sculptures of Woolworth himself, counting out nickels and dimes to pay for the work, and Cass Gilbert hugging a model of the building, while Teddy Roosevelt is watching it all through an amused monocle.

Amazingly, the Woolworth Building suffered no structural damage from the collapse of the Twin Towers on September 11, although the building’s electricity and telephone systems were knocked out for a few weeks. The terrorist attacks did, however, result in the closure of the magnificent lobby to the public, thus robbing New Yorkers of access to one of the great sights of the city. If you persist, the guards will sometimes allow you to take a quick peek—it’s well worth a try.

The Woolworth Building held the title of TALLEST BUILDING IN THE WORLD for 17 years, until overtaken by the Bank of Manhattan Trust Building at No. 40 Wall Street in 1930. It remained the headquarters of Woolworth for nearly 85 years until the company went bankrupt in 1997, when the building was sold to the Witkoff Group.

No. 259 Broadway

The VERY FIRST TIFFANY STORE was opened at No. 259 Broadway on September 14, 1837, by CHARLES LEWIS TIFFANY and TEDDY YOUNG. On the first day of opening, sales at the Tiffany and Young Fancy Good Store, as it was then known, totaled $4.98. In 1841 the store vacated this address and moved farther uptown, eventually opening its famous flagship store on Fifth Avenue in 1940. In 2006 Tiffany returned to its Lower Manhattan roots, opening a store at No. 37 Wall Street.

No. 259 Broadway stood above NEW YORK’S FIRST SUBWAY STATION, the only station on NEW YORK’S FIRST SUBWAY, THE BEACH PNEUMATIC TRANSIT, which opened on February 26, 1870. The subway was the brainchild of ALFRED BEACH, an inventor and editor of Scientific American magazine, who had to build his air-driven subway system in secret to avoid the objections of Broadway store owners, such as A. T. Stewart, who opposed the idea. The single-track tunnel ran east from the station beneath No. 259 Broadway, turned south and then ran under the middle of Broadway for 300 ft (91 m) as far as Murray Street. Beach’s subway remained open for public demonstration until 1873, when a financial crisis put an end to the project. The tunnel, and the remains of the wooden subway car, were rediscovered in 1912 by engineers constructing the Brooklyn Manhattan Transit subway. No. 259 Broadway no longer exists, and the site is now occupied by an eight-story office block with the address No. 258 Broadway.

A WALK AROUND THE CIVIC CENTER

Start point: Broadway and Park Row

Park Row

PARK ROW runs northeast from Broadway toward the Civic Center. In the late 19th century it was lined with the offices of major newspapers who wanted to be close to City Hall, and was known as “Newspaper Row.” The New York Herald was at the Broadway end, then came the New York Times, the New York Tribune, and the New York World.

Park Row Building

Walk up Park Row to No. 15, the PARK ROW BUILDING, which at 391 ft (119 m) high was THE TALLEST SKYSCRAPER IN THE WORLD when it was completed in 1899, but was overtaken by the long-gone Singer Building on nearby Broadway in 1908. Distinctive features of the Park Row Building are the twin copper-clad domes at the top, which served as observatories, and four life-size sculpted figures projecting above the entrance. The building served as the headquarters of the INTERBOROUGH RAPID TRANSIT COMPANY and as the first offices of the ASSOCIATED PRESS.

Potter Building

At No. 38, on the corner with Beekman Street, stands the glorious redbrick POTTER BUILDING, built in 1886 and famous for its pioneering use of fire-resistant terra-cotta. The Potter Building replaced the World Building, the first headquarters of the New York World, which burned down in 1882. THOMAS EDISON gave THE FIRST PUBLIC DEMONSTRATION OF HIS TINFOIL PHONOGRAPH, the FIRST MACHINE THAT COULD RECORD AND REPRODUCE SOUND, in the offices of the Scientific American magazine at the World Building on December 7, 1877.

Next to the Potter Building, at No. 41, is the old NEW YORK TIMES BUILDING, now part of Pace University. The newspaper moved from here to Times Square in 1904. The open space across Spruce Street is known as PRINTING HOUSE SQUARE and is dominated by a statue of BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, seen here in his role as a publisher, brandishing a copy of his Pennsylvania Gazette.

Across Park Row, in City Hall Park, there is a statue of another publisher, HORACE GREELEY, founder and editor of the New York Tribune, whose offices were on the north side of Printing House Square. The NEW YORK TRIBUNE BUILDING was built in 1875 and was one of the first office blocks to have high-rise elevators.

New York World Building

Next to the Tribune stood the NEW YORK WORLD BUILDING, commissioned in 1883 by JOSEPH PULITZER, who had bought the New York World newspaper earlier in that year. When completed in 1890 the New York World Building was THE TALLEST SKYSCRAPER IN THE WORLD, 308 ft (94 m) high, and THE FIRST BUILDING IN NEW YORK TO SURPASS THE HEIGHT OF THE 284 FT (86 M) HIGH SPIRE OF TRINITY CHURCH. Pulitzer had his office in an enormous dome at the top of the building, from where he could look down on all the other newspapers.

In 1896 he launched the world’s FIRST COLOR SUPPLEMENT, but perhaps his greatest legacy was the PULITZER PRIZE, awarded annually for achievements in journalism, photography, and literature. The prizes were established with a bequest from Pulitzer’s will to Columbia University, which administers the awards.

Both the World and Tribune Buildings were demolished in 1955 to make way for the extensions of the entrance ramps to the Brooklyn Bridge.

City Hall Park

Lining the west side of Park Row is CITY HALL PARK, originally a pasture for livestock known as THE COMMONS. At one time or another the Commons was home to almshouses, a debtors prison, barracks, and a post office, but its main function was as New York’s village green. In 1765 New Yorkers gathered here, in THE FIRST MASS PUBLIC DEMONSTRATION AGAINST THE BRITISH, to protest about the STAMP ACT, before marching off to Bowling Green to burn the governor in effigy. The following year the first of five LIBERTY POLES was raised on the Commons—these were flagstaffs erected as symbols of defiance, and there is a replica of one now located on the Broadway side of the park.

Nathan Hale

A little to the north of the Croton Fountain, facing City Hall, is a huge bronze of the young revolutionary hero NATHAN HALE (1755–76), who made a daring attempt to infiltrate behind the enemy British lines in New York, disguised as a Dutch schoolteacher, to gather intelligence about British troop movements. He was captured and, on the morning of September 22, 1776, hanged on a gallows specially erected by the Dove Tavern at 63rd Street and First Avenue. He was 21 years old. His final words, as reported by a British officer who witnessed the hanging, went down in American legend. “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.” The statue, sculpted by Frederick MacMonnies, stands on a pedestal by Stanford White, and is an idealized representation of Hale since there were no portraits of him for the sculptor to work from. It was dedicated by the Sons of the Revolution of New York on the 110th anniversary of Evacuation Day, November 25, 1893.

On July 9, 1776, the DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE was read out on the Commons to George Washington and his troops, after which the crowd marched down to Bowling Green once again, this time to topple the statue of King George III.

In the middle of the park stands a delightful fountain designed in 1871 by Jacob Wrey Mould, who helped to lay out Central Park. This fountain replaced the original CROTON FOUNTAIN, AMERICA’S FIRST DECORATIVE FOUNTAIN, which was erected in 1842 to celebrate the opening of the Croton Aqueduct, bringing fresh water to the city. The Croton Fountain was fed with water from the aqueduct, and for the first time in their history New Yorkers had enough water to power a fountain that could propel water 50 ft (15 m) into the air.

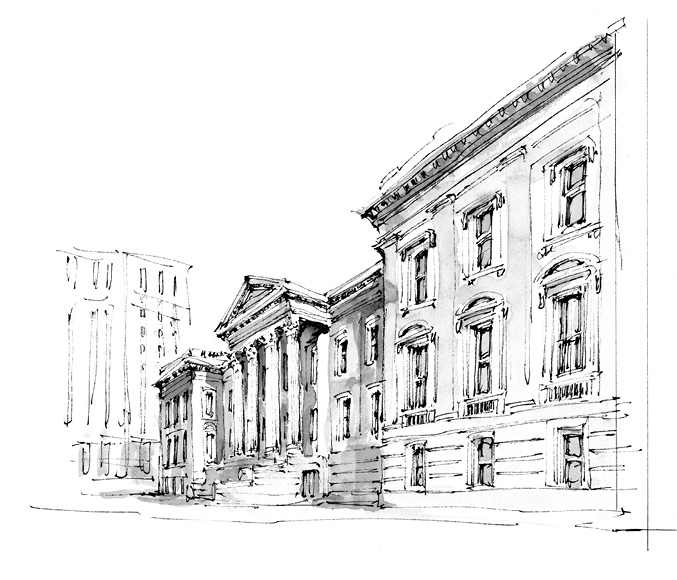

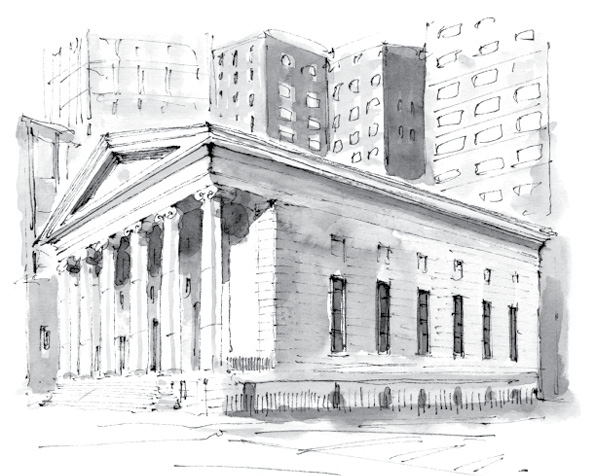

City Hall

THE NEW CITY HALL was officially opened in 1812, replacing the old hall on Wall Street. It was designed and built by JOSEPH MANGIN, who largely took care of the mildly French Renaissance exterior, and JOHN MCCOMB JR., who laid out the handsome interior with its sweeping marble staircase and Rotunda. The exterior was clad with marble, all except for the north side which was brownstone—since the hall was built at the northern extremity of the city, there wasn’t anyone important living north of it to be offended. The whole building was refaced with limestone in 1954.

The splendid GOVERNOR’S ROOM inside houses a portrait gallery of prominent early New Yorkers and includes John Trumbull’s 1805 portrait of Alexander Hamilton, which appears on the ten-dollar bill.

In 1865 ABRAHAM LINCOLN lay in state beneath the Rotunda, as did ULYSSES S. GRANT, 20 years later in 1885.

DEWITT CLINTON (1769–1828) was the first mayor to move in when the new City Hall was opened. He was the nephew of New York’s first and longest-serving state governor, George Clinton, known as the “Old Incumbent.” As such, it seems DeWitt was born to run New York, which he did, on and off, as mayor for 12 years between 1803 and 1815, and as state governor for eight years during two terms between 1817 and 1828. While in office he championed and oversaw many important projects, including one in particular that would shape New York forever.

Manhattan Street Grid Plan

Officially known as the COMMISSIONERS PLAN OF 1811, the MANHATTAN STREET GRID PLAN was designed to promote the orderly development and growth of New York north of 14th Street. The city was expanding so rapidly, and space on the island was so restricted, that some sort of method was needed to ensure that best use was made of the land available, and that there was a “free and abundant circulation of air” to ward off disease.

The Commission was made up of three members, the much respected Founding Father, signer of the Constitution, and author of much of it, GOUVERNEUR MORRIS; lawyer JOHN RUTHERFORD; and the surveyor-general of the State of New York, SIMEON DE WITT, DeWitt Clinton’s first cousin.

Observing that “straight-sided and right-angled houses are the most cheap to build,” the commissioners came up with a regular grid of straight east–west streets and north–south avenues that more or less ignored the topography of the island.

The twelve numbered avenues, running roughly north–south parallel with the Hudson River, begin with First Avenue in the east and finish with Twelfth Avenue in the west. Fifth Avenue is the dividing line between the east and west streets. The bulge on the lower part of the island east of First Avenue, which would become the East Village, was given four additional avenues lettered A to D, earning the nickname ALPHABET CITY.

The numbered east–west streets are 60 ft (18 m) wide and a fairly regular 200 ft (60 m) apart, meaning that along the avenues there are 20 blocks to a mile. The avenues are 100 ft (30 m) wide, but the distance between them varies slightly, while Lexington and Madison Avenues were inserted at a later date to relieve congestion and create more corner lots on the overcrowded East Side.

The idea originally was to dispense with Broadway above 14th Street, because its ancient route cut diagonally across the grid, but such was the outcry that Broadway was permitted to stay, which allowed for the creation of wonderful triangular squares and open spaces wherever it meets the grid.

The actual survey for the grid was performed by JOHN RANDEL JR. and his team, who personally walked out every one of the some 2,000 city blocks between 14th Street and Harlem. They were empowered to enter private property and unsurprisingly were often met with hostility. As much as was possible they allowed existing properties to remain in situ, while those whose properties had to be removed were compensated.

With a number of modifications, the most spectacular being the creation of Central Park in 1853, the plan was implemented more or less as envisioned by the commissioners and has survived for more than 200 years as an essential part of New York’s identity.

Erie Canal

DeWitt Clinton also oversaw the creation in 1825 of THE WORLD’S LONGEST CANAL, the ERIE CANAL, known as “Clinton’s Ditch,” linking the Hudson River at Albany with the Great Lakes. Almost overnight this secured New York’s place as the nation’s commercial capital by providing a quick and relatively cheap route for raw materials and goods to travel from the heart of the Midwest to New York.

Tweed Courthouse

North of City Hall is the monumental Victorian neoclassical New York County Courthouse, popularly known as the “TWEED COURTHOUSE” after Tammany Hall boss William Tweed. Tweed used the building project to embezzle millions of dollars from the budget, which soared from $3 million to $14 million during construction between 1861 and 1871. Some $9 million of that went into Tweed’s pocket, more than the U.S. government spent on buying the whole of Alaska. Such was the scale of the larceny that even hardened New Yorkers were shocked into action, particularly when municipal taxes were raised to pay for it, and Tweed was eventually tried in his own unfinished courthouse in 1871 and sent to jail.

The building remained in use as a courthouse until 1926, then served as offices, and since 2002 has been the headquarters of the Department of Education.

Tammany Hall

TAMMANY HALL was a powerful political organization founded in 1788 for ordinary working people as a counter to New York’s more exclusive clubs for the rich, and it ran New York for much of the 19th century. Formed in New York as the SOCIETY OF ST. TAMMANY it took its name from a legendary 17th-century Indian chief named Tamamend, who was believed to have befriended William Penn, and adopted Indian rituals and titles, such as “braves” for the newest members, and “Grand Sachem” for the leader. Headquarters was known as “the wigwam.”

Tammany Hall soon became deeply political in its pursuit of universal male suffrage and laws to protect working men, and was rewarded with federal jobs for supporting the Democratic presidency of Andrew Jackson in 1828. It bolstered its political base by helping immigrants find jobs and gain citizenship, and was seen as a champion of New York’s working poor. Gradually Tammany Hall began to use violence and corruption to get its way, intimidating people to vote for those it supported and putting its own people into positions of influence and power.

Municipal Building

Now walk round to the north side of Tweed Courthouse and cross Chambers Street to the beaux arts Surrogates Court and Hall of Records, which holds the public records of New York going back to 1664.

Boss Tweed

The most notorious of Tammany Hall’s leaders was WILLIAM “BOSS” TWEED, who became Grand Sachem in 1858. Born in Cherry Street on the East Side, in 1823, Tweed learned to play rough as foreman of one of New York’s notoriously violent volunteer firefighting companies, who often fought each other to the death for the right to attend a fire. Having survived that, fighting his way to the top of Tammany Hall was easy for Tweed. He got himself elected to the influential New York County Board of Supervisors, from which position he was able to ensure that his cronies were elected to powerful positions in the city government, making up what became known as the “Tweed Ring.” Contracts for any kind of public work would go only to those who paid the Tweed Ring a percentage, which made the Ring millions of dollars—some estimates reckon that, during the ten years they were operating, the Tweed Ring embezzled up to $200 million.

They finally overstretched themselves with the Tweed Courthouse contract. Up until then they had managed to avoid exposure by paying off journalists and threatening editors with pulling the city’s advertising from their newspapers, but in 1869 cartoonist THOMAS NAST began lampooning Tweed in Harper’s Weekly, and in 1870 the Republican-supporting New York Times published a series of exposés about the Ring. Their time was up.

Despite the misdemeanors of “Boss” Tweed and others like him, Tammany Hall continued to flourish as an influential political machine until Franklin D. Roosevelt stripped them of federal patronage in the 1930s, and by the 1960s the organization had ceased to exist.

Turn right and walk east to where the enormous bulk of the MUNICIPAL BUILDING looms above the Civic Center, straddling Chambers Street. Standing 580 ft (176 m) high, one of the largest government buildings in the world, and THE FIRST BUILDING IN NEW YORK TO INCORPORATE A SUBWAY STATION IN THE BASEMENT, the Municipal Building was constructed in 1914 to accommodate the added bureaucracy created by the union of the five boroughs. Its monumental design is said to have inspired a number of civic buildings in Moscow, including the main building of Moscow State University.

Turn left (north) along Center Street and walk into Foley Square, which is dominated on the east side by the classical columns of the United States Courthouse, the last work of Cass Gilbert, and the hexagonal New York County Courthouse, built in 1926 to replace the Tweed Courthouse.

Foley Square

FOLEY SQUARE, which sits at the very heart of New York’s Civic Center district, was named after THOMAS F. “BIG TOM” FOLEY (1852–1925), a saloon keeper and prominent Tammany Hall politician.

Collect Pond

The square sits on the site of the COLLECT POND, early New York’s principal source of fresh water. The pond was fed by underground springs, covered 50 acres (20 ha), and was so deep, up to 60 ft (18 m) in some places, that there were reported sightings of monsters. In the summer people would come up from the city and sit by the pond to picnic, or they would skate on it in winter, but by the beginning of the 19th century the pond had become so polluted with waste from the nearby slaughterhouses and tanning yards that it was decided to get rid of it. A canal was dug to drain the water into the Hudson River and by 1813 the pond had been filled in. Homes were put up on the reclaimed land, and the area became a respectable middle-class neighborhood clustered around “Paradise Park.” The canal was later also filled in to create Canal Street.

Five Points

However, the underground springs that had fed the Collect Pond continued to rise, and after a few years the area became boggy and waterlogged, the houses started to sink, and the whole area was soon knee deep in foul-smelling mud. The middle-class inhabitants fled, leaving the place to be inhabited by the poor, mainly Irish immigrants fleeing Ireland’s potato famine. The neighborhood became New York’s most notorious slum, known as FIVE POINTS since it was centered around the junction of five streets. By the middle of the 19th century Five Points was ruled by vicious gangs, mainly Irish, as portrayed in the 2002 film Gangs of New York, based on the book by Herbert Ashbury.

At the end of the 19th century the Five Points area was finally razed and transformed into the city’s Civic Center, but even today the buildings that stand on the site of the Collect Pond require regular pumping out to prevent flooding from rising spring water.

Croton Aqueduct

The loss of the Collect Pond meant that rapidly expanding New York now had a water supply problem, and to solve this it was decided to bring in water from the CROTON RIVER 40 miles (64 km) north of the city in Westchester County. The river was dammed and gravity brought the water down along a raised iron pipe to the Bronx, where it crossed the Harlem River into the city over the High Bridge Aqueduct at the end of 173rd Street. The water then flowed down the west side of Manhattan into the RECEIVING RESERVOIR, now the site of the Great Lawn in Central Park. From here it was sent to the DISTRIBUTING RESERVOIR, a vast Egyptian-style structure located where the New York Public Library now stands. The opening of the Croton Aqueduct system on October 14, 1842, was celebrated with a triumphant jet of water leaping 50 ft (15 m) into the air from a specially built fountain in City Hall Park.

Today, fresh water is brought to the city from the Catskill Mountains and flows by gravity along three tunnels under the city. It rises again under natural pressure through numerous specially constructed shafts.

Return to Center Street, turn left (south) past the front of the Municipal Building, and make your way across all the traffic islands back to Printing House Square. Walk past the statue of Ben Franklin and continue south on Nassau Street for three blocks. Turn left (east) onto Fulton, and continue until you come to the TITANIC MEMORIAL LIGHTHOUSE, brought here in 1976 from its former location on the roof of the now demolished Seamen’s Church Institute farther down on South Street.

South Street Seaport

Cross Water Street to the SOUTH STREET SEAPORT MUSEUM, founded in 1967 by a group of residents led by Peter and Norma Stanford, who wanted to preserve the area as the historic site of New York’s original port. The museum now stands at the heart of 12 square blocks that contain a greater concentration of restored early 19th-century commercial buildings than anywhere else in New York.

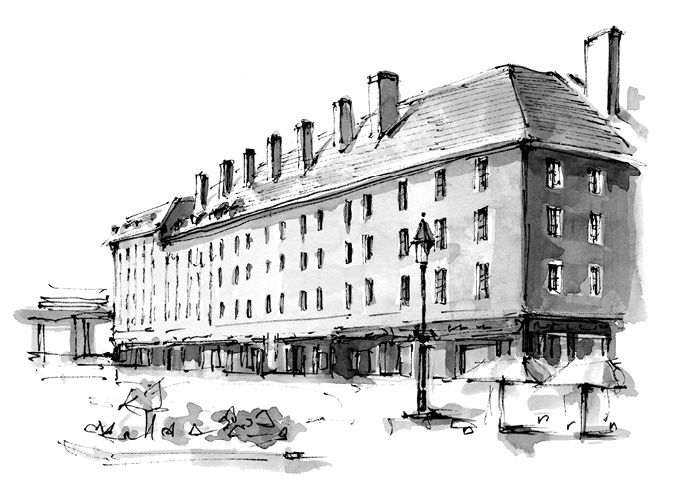

Carry on down Fulton and on the right is the beautifully restored SCHERMERHORN ROW, built in 1811 by ship chandler Peter Schermerhorn as warehouses on land reclaimed from the East River. Shops were opened on the ground floor to serve customers using the Fulton Ferry between Manhattan and Brooklyn, and the buildings now house restaurants and galleries as well.

Across South Street is the former site of New York’s main wholesale fish market, the FULTON FISH MARKET, which moved to the Bronx in 2005. Along with PIER 17, which extends out onto the water, this area has now been transformed into a shopping mall with restaurants and bars that line the waterfront and affords stunning views of the Brooklyn Bridge, Brooklyn Heights, and the harbor.

A splendid place to finish our walk.

Brooklyn Bridge

A very pleasant excursion on a fine day is a walk across New York’s grand old lady, the BROOKLYN BRIDGE. There is a walkway running along the middle of the bridge, above the roadway, that affords a uniquely thrilling view of the city and the harbor, as well as allowing you to get a close-up look at a magnificent piece of engineering.

When completed in 1883 the Brooklyn Bridge, with a central span of 1,595 ft (486 m), was the LONGEST SUSPENSION BRIDGE IN THE WORLD, over half as long again as any bridge previously built. It was also the first to be made of steel. The iconic Gothic double arches, 271 ft (83 m) high, were designed as symbolic gateways to the two communities linked by the bridge, New York and Brooklyn, which were separate cities at that time.

The Brooklyn Bridge was the brainchild of German-born engineer John A. Roebling, who conceived of the idea while marooned on the East River in an ice-bound ferry to Brooklyn. He never got to see his masterpiece. Just before construction started in 1869 he died from a tetanus infection picked up after his foot had been crushed between a ferry and a piling while he was conducting a survey for the bridge. Roebling’s son Washington took charge of the project, but a year later he too was incapacitated, after suffering the bends while coming up from a caisson on the riverbed beneath one of the towers. Washington managed to finish the project by relaying instructions to the building team via his wife, while he watched the proceedings from his house on Columbia Heights through a telescope.

Well, I never  knew this

knew this

about

LOWER BROADWAY—VESEY TO CHAMBERS. THE CIVIC CENTER

One block west of Broadway, on the corner of Barclay and Church Streets, is OLD ST. PETER’S CHURCH, built in 1836 and THE OLDEST CATHOLIC BUILDING IN NEW YORK. The first St. Peter’s, built on this site in 1785, was THE FIRST CATHOLIC CHURCH IN NEW YORK and the parish church of THE FIRST CATHOLIC PARISH IN NEW YORK. In 1800 the parish opened NEW YORK’S FIRST CATHOLIC SCHOOL. Elizabeth Ann Seton, America’s first native-born saint, was received into the Catholic church at St. Peter’s in 1805.

In 2001 the body of the first officially recorded victim of the terrorist attacks, the Catholic priest FATHER MYCHAL JUDGE, chaplain to the New York City Fire Department, was brought to St. Peter’s Church by firefighters and laid before the altar.

The Woolworth Building served as the headquarters of Mode Magazine in the TV series Ugly Betty.

The first offices of the project to develop the atomic bomb were opened on the 18th floor of No. 270 Broadway in 1942. Because it was located in Manhattan, the project was given the codename the MANHATTAN PROJECT, a name it kept even though the headquarters was moved to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, the following year.

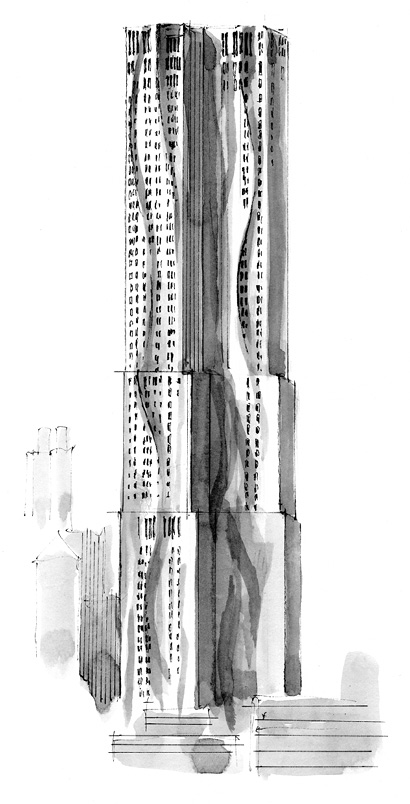

Swaying precariously above Printing House Square at No. 8 Spruce Street is an extraordinary stainless steel and reinforced concrete skyscraper called NEW YORK BY GEHRY, 870 ft (265 m) high and THE TALLEST RESIDENTIAL BUILDING IN THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE. It was opened in 2011 and designed by Frank Gehry in such a way that it seems to undulate and ripple.

Underneath City Hall, hidden from public view, sits THE MOST BEAUTIFUL SUBWAY STATION IN NEW YORK. City Hall was the starting point for NEW YORK’S FIRST SUBWAY, THE INTERBOROUGH RAPID TRANSIT (IRT), which ran north from City Hall along Lafayette and Lexington to 42nd Street, then west to Longacre (now Times) Square, and finally north again to Harlem. HEINS AND LAFARGE, the architects who designed the early subway stations, intended City Hall to be their “pièce de résistance.” Not only was this the first station on the line, but the track made a huge loop here to enable the trains to turn around, and this allowed them to give full rein to their imagination. Heins and LaFarge were the original architects of St. John the Divine Cathedral, and City Hall station became the cathedral of the subway. There are vast, vaulted ceilings, arches lined with terra-cotta tiles by the pioneering Spanish architect Rafael Guastavino, colored decorative tiles on the walls, and warmly glowing chandeliers. On opening day, October 27, 1904, 100,000 people came to have a look and for years afterward New Yorkers, with no intention of riding the subway, would come down just to sit and gaze. In 1945 the trains were switched from five cars to ten, too long for the City Hall station’s curving platforms to accommodate, and the station was closed, its glories becoming but a fading memory to all but a privileged few. Although the southbound No. 6 trains still used the loop to turn round, passengers were made to get off at the station before. Today, however, the guards will let you stay on board as the train makes its turn, and if you look out of the right-hand side of the train you should be able to see for yourself the majestic, secret cathedral of the subway.

Look out for the Tweed Courthouse in the following films: Gangs of New York, Dressed to Kill, The Verdict, and Kramer vs. Kramer.

Exterior scenes for the classic 1957 film 12 Angry Men, starring Henry Fonda, were filmed outside the New York County Courthouse, which also features frequently in the television series Law & Order.

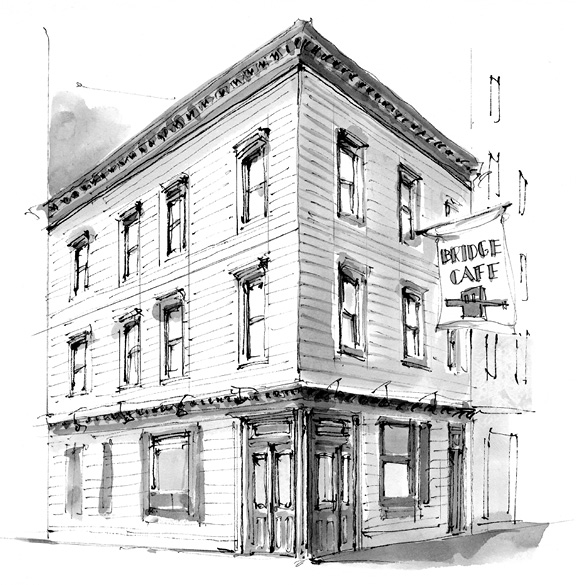

On the corner of Water Street and Dover Street sits one of the several claimants to the title of NEW YORK’S OLDEST BAR, the BRIDGE CAFÉ, which has been operating here since 1847 in a building dating from 1794. It is definitely NEW YORK’S OLDEST BUSINESS. Mayor Ed Koch used to have a private table here where he would hold court twice a week.

There is a plaque on Pearl Street, where it runs under the approach to the Brooklyn Bridge, marking the site of the FIRST PRESIDENTIAL MANSION, Osgood House, which had the address No. 1 Cherry Street. George Washington lived here during the run-up to his inauguration in 1789 and for the first few months of his term of office as the 1st president of the United States. The house was the forerunner to the White House, and contained the first presidential office (now called the Oval Office) and the first public business office (now called the West Wing). The household was run by Samuel Fraunces, who had previously owned Fraunces Tavern. After ten months Osgood House became too small for the rapidly expanding executive office, and in February 1790 Washington moved to the larger McComb Mansion on Broadway (see page 38).