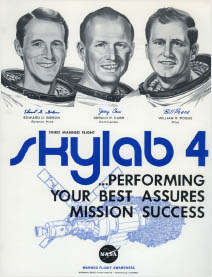

Skylab 4, the third and final manned visit to the OWS that wrapped up the Skylab program, lasted nearly three months and included four space-walks totaling almost twenty-four hours. The all-rookie crew was led by CDR Gerald Carr, with William Pogue as PLT and Edward Gibson as SPT. Although a successful flight, the mission was affected beyond the first month by an admittedly awkward reluctance by the astronauts and Mission Control to openly discuss workload and scheduling issues.

It was booster problems, however, that delayed the launch. Chrysler had used high-strength aluminum alloys for the Saturn IB’s first-stage tail-unit assembly—including its eight stabilizing and support fins, which engineers knew were subject to stress-induced corrosion cracking. On November 6, 1973, five days before the planned liftoff, an inspection after a fueling test four days earlier, which was intended to look for signs of stress corrosion, found fifteen tiny cracks in the fins. The cracks—around bolts in the rear spar fittings, where the fins were attached to the tail unit—were blamed on a combination of the salty ocean air around Complex 39, the stresses of fueling, and age. (The SA-208 booster was assembled in 1966.)

Replacement fins were flown in from NASA’s Michoud, Louisiana, Saturn assembly facility, and all eight fins were replaced at Pad 39B from November 9 to 12. Reinforcement fittings were also installed. On November 12, technicians discovered larger but less worrisome cracks in seven of the eight support beams in the interstage ring, between the first and second stages. The beams were strengthened with aluminum bracing, and launch was set for November 16.

Skylab 4 got underway on schedule at 9:01 a.m. (EST), with docking at the Skylab cluster eight hours later. Because of the previous crew’s early motion sickness, all three astronauts took medication; all three were nonetheless affected at first, with the motion sickness hitting Pogue particularly hard.

The crew’s handling of the situation got the flight off to a rocky start with Mission Control. They spent the first night in the CM, and between tracking station coverage, Carr and Gibson debated what they should say during the evening status report, apparently forgetting that the CM’s onboard tape recorder was running. They decided that Carr would report Pogue’s nausea but not his vomiting, and he would report that Pogue had not been hungry.

Launch: 9:01 a.m. (EST), November 16, 1973 (photo by Tom Usciak)

On orbit: TV image of a Christmas tree made of food containers, December 24

Splashdown: 8:17 a.m. (PDT), February 8, 1974

The next morning, after a good night’s sleep, they all felt better, and at 9:15 a.m. they entered the OWS—where they learned that the onboard recorder tapes had been routinely downloaded and transcribed, revealing Carr and Gibson’s candid conversation. Mission Control called for a medical conference in midafternoon, and Astronaut Office Chief Alan Shepard later came on the line to give the crew a public reprimand. “I just wanted to tell you,” he said, “that on the matter of your status reports, we think you made a fairly serious error in judgment here in the report of your condition.” Carr replied, “Okay, Al, I agree with you. It was a dumb decision.”

They got to work, but transferring the supplies they had brought, activating the OWS, and working with experiments proved overwhelming. Soon they were tired and behind schedule. Mission planners and experimenters only added to the workload. Planning for the new experiments was sometimes inadequate, and the crew would later report that they had never been trained for some of the experiments. Though the astronauts called their pace frantic, Houston, remembering the pace of the Skylab 3 crew, believed they were not working long or hard enough.

Six days into the mission, on Thanksgiving Day, Pogue and Gibson conducted the first EVA, which lasted six hours and thirty-four minutes. They replaced the ATM film and repaired a malfunctioning antenna on an Earth resources experiment package on the airlock truss, using a repair kit they had brought just for the job.

The next day, one of the gyroscopes in the Skylab cluster’s attitude control system overheated; the issue was blamed on insufficient lubrication. It was shut down. The station used three large gyroscopes, sized so that any two of them could provide sufficient attitude control, with the third as a backup if one failed. Mission Control, however, called the problem more of a nuisance than anything and even developed a plan for the system to operate on only one gyroscope if necessary. Later in the mission, a second gyro showed similar problems, but temperature control and load-reduction procedures kept it operating (at reduced speed).

From December 18 to 26, the Soviet manned flight Soyuz 13 was on orbit. It was the first time the Soviets and the United States had manned crews in space at the same time, although the two spacecraft were never in the same orbital plane.

On Christmas Eve, the astronauts’ families gathered in the MOCR 1 at JSC, and the crew sent back live video of a tree they had built from food containers.

On Christmas Day, Carr and Pogue began an EVA that would last for just more than seven hours, setting a duration record not broken until a 1985 Space Shuttle mission. In addition to reloading ATM film; pinning open a balky aperture door on the UV solar camera; and freeing a jammed filter wheel in the X-ray telescope, the astronauts took two cameras to photograph Comet Kohoutek. Czech astronomer Luboš Kohoutek had first spotted the comet on March 7, 1973; extensive observations of it were then added to Skylab 4’s mission, increasing the crewmen’s workload. The astronauts first saw it on December 13. Based on its unusual brightness, the comet had been predicted to become a spectacular sight in the night sky.

By December 25, the crewmen had no trouble keeping up with their work, but Houston’s inflexible scheduling and approach to operations was still an extreme annoyance. The astronauts agreed that they needed to reach a better understanding with the flight planners. On December 28, at the mission’s halfway point, Carr taped a six-minute request for a frank discussion with Mission Control.

In late January, Gerald Carr clings to the Rotating Litter Chair in the experiments compartment as part of Experiment M131, Human Vestibular Function, which investigated space motion sickness. The chair could be used in a rotating or “tilt litter” mode, and could spin a seated subject up to thirty rpm. Equipment stowage pockets are on the wall behind Carr.

During two hours of conversations with CAPCOM Richard Truly on December 30, the air was finally cleared. It had taken nearly seven weeks. Everyone was relieved to find that candid conversations could be held on the open communications channel without any repercussions. Carr, who was not prone to rocking the boat, later regretted having waited so long to broach the subject. The flight controllers acknowledged that they had not considered that this crew might have a different approach to their duties from the first two.

The next day, Carr and Gibson conducted the flight’s third EVA, which was devoted to Kohoutek observations and photography and lasted three and a half hours. The comet had swept out from behind the sun on December 30, and then had dimmed; a week later, even the astronauts had trouble seeing it.

As was the case for the previous two missions, solar observations with the ATM were a central objective. The crew recorded about seventy-five thousand new X-ray, UV, and visible light images of the sun. On January 21, 1974, Gibson filmed the first recording from space of the birth of a solar flare to maturity.

Carr and Pogue operated the Earth photography and measurement experiments. One crewman photographed the classified USAF Area 51 facility in Nevada, despite specific instructions against doing so. NASA prevailed in a fight with the Pentagon over releasing the image with the rest of the photos, although the photograph went unnoticed until 2006.

On the morning of February 3, Carr and Gibson handled the mission’s final EVA—lasting three hours and nineteen minutes—to retrieve the ATM film and some particle-collection experiments.

After eighty-four days, Skylab 4 ended with splashdown at 8:17 a.m. (PDT) on February 8, 1974. USS New Orleans recovered the crew and CM from the Pacific Ocean, 176 miles southwest of San Diego, California. Although it was the longest manned flight to date, the Soviets would easily break Skylab 4’s record by 1978. They had been steadily gaining experience in long-duration manned flights aboard their space stations (first launched in 1971)—a capability they would build on for the next twenty years.

The Skylab cluster came to a fiery end in Earth’s atmosphere during reentry on July 11, 1979, with some pieces landing in Australia.

Gibson, Carr, and Pogue with a T-38 at Ellington AFB on November 13, 1973, before heading to Patrick AFB. That evening, NASA managers set November 16 for launch, after analysis showed that tiny cracks in the support structure between the Saturn’s stages would not be a concern during flight.

William R. Pogue, forty-three, suits up for an altitude chamber test at KSC on August 2, 1973. A USAF lieutenant colonel, Pogue had been a fighter-bomber pilot during the Korean War, and he was later a member of the Thunderbirds. He had also been a math professor at the Air Force Academy and a test pilot for the Royal Air Force. Like Carr, Pogue had been penciled in for the crew of the canceled Apollo 19. He would spend thirteen and a half hours outside the OWS on two EVAs. Skylab 4 was the only space flight for each of the three crewmen.

Edward G. Gibson, thirty-seven, Skylab 4 science pilot (SPT), also during suiting on August 2. The civilian Gibson earned his doctorate in engineering, with a minor in physics, from the California Institute of Technology in 1964. He had been a research scientist at Philco working on lasers before joining NASA in 1965, as part of the six-member scientist-astronaut class. He then earned his Air Force wings after a year of flight training at Williams AFB in Arizona.

CDR Gerald P. Carr, forty-one, a Marine Corps lieutenant colonel, suits up on August 2 alongside suit tech Troy Stewart. Carr had been a carrier-based fighter pilot. He earned a bachelor of engineering degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Southern California in 1954, a bachelor of science degree in aeronautical engineering from the US Naval Postgraduate School in 1961, and a master of science degree in aeronautical engineering from Princeton University in 1962. Carr was the first rookie commander of a US space flight since 1966, when Neil Armstrong helmed Gemini VIII.

The S-IB first stage of Skylab 4’s Saturn booster (SA-208) in the VAB’s transfer aisle on July 27, 1973, during processing. On June 20, the stage had arrived at KSC by barge from the Michoud Assembly Facility near New Orleans, Louisiana. It had been static test–fired at MSFC in 1966 and then stored at Michoud until 1972. (photo by Steve Nolte)

The crew poses at Pad 39B with NASA photographers on November 8, 1973, two weeks into the astronauts’ preflight quarantine. Left to right : Ed Thomas, Bill Taub, Gibson, Carr, Pogue, and Larry Summers (with an Arriflex S 16mm camera).

The Skylab 4 stack crawls past Florida scrub oak trees to Pad 39B on ML-1 on August 15, 1973. Some 1,500 guests from surrounding communities were on hand to view the beginning of the rollout at 7:00 a.m. (EDT).

Carr at the airlock module hatch, a modified Gemini spacecraft hatch, in the Skylab trainer in Bldg. 5 at JSC on August 12, 1973.

The booster’s original fins, at Pad 39B on November 10, 1973. Members of the “Fin Team,” who accomplished the change-out, were provided with VIP launch seats.

Carr combs Pogue’s hair before a photo session with a large Skylab model at JSC on August 10, 1973. The crew was preparing to conduct a simulated EVA using the Skylab trainer.

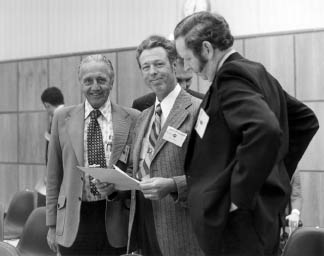

KSC Director Kurt Debus, Spacecraft Operations Chief Engineer George T. “Ted” Sasseen, and Dick Smith, Saturn program manager at MSFC, at the Flight Readiness Review in the MSOB on October 18, 1973.

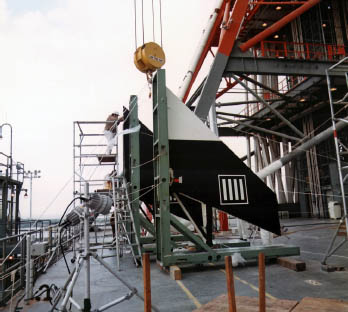

The first of eight fins are removed from the Saturn IB’s first stage at Pad 39B on November 9, 1973. Three days earlier, hairline cracks were discovered around bolts in the fittings that attached the fins to the booster’s tail unit. Most were less than an inch long and were described as stress corrosion cracks.

Sunset at about 6:30 p.m. on November 15 at Pad 39B, with the MSS still in place. First-stage propellant loading would begin within hours. (photo by Mark Usciak)

left to right : Chief Test Planning Officer Bob Moser, Test Supervisor Chuck Henschel, Chief Test Supervisor Bill Schick, and Assistant Launch Vehicle Test Conductor Tip Talone in Firing Room 3 on November 5, 1973, during the countdown toward the original launch date of November 10.

Director of Launch Vehicle Operations Hans Gruene in Firing Room 3 on November 5. Gruene, a German rocket engineer who was part of Operation Paperclip, had first come to the Cape in 1952 to help establish what would become the Eastern Test Range.

Skylab 4 clears the LUT at 9:01 a.m. (EDT) on November 16 in this view looking north. NASA invited thirty thousand guests to the launch, and an additional ten thousand government and contractor personnel attended. Brevard County officials correctly forecast a low turnout and made no special provisions; public spectators were estimated in the tens of thousands.

Skylab 4 clearing the LUT, view from below

A flock of birds flies past the pad as, minutes after liftoff, water continues to drain from the LUT’s swing arms and the launch pedestal.

Gibson enters the upper dome area of the OWS through the hatch to the airlock module. Blue handrails and four general illumination fluorescent lights are mounted on the dome. The red stripe on the light at far right indicated it as an initial entry and emergency light. The air duct next to Gibson’s arm at left provided environmental control in the airlock module.

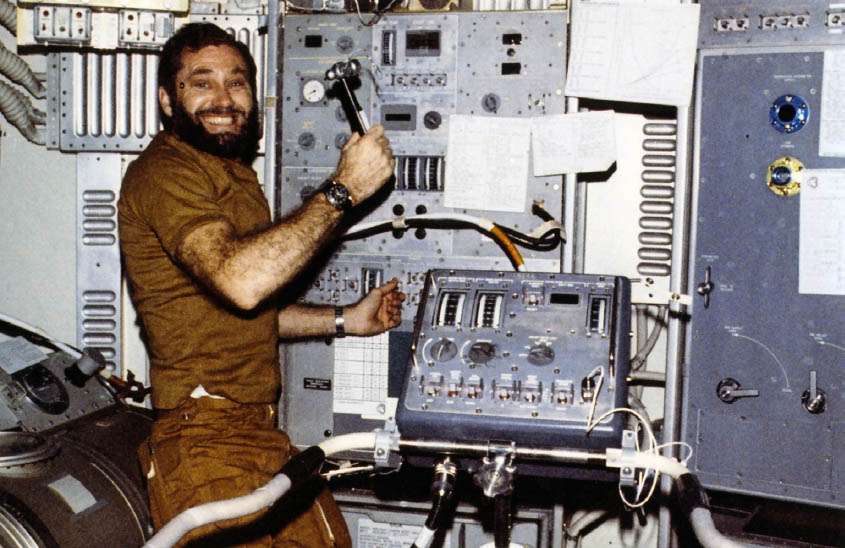

In this gag photo, taken near the end of the mission in the experiments compartment, Pogue seeks revenge on the Experiment Support System, which centralized power, displays, and controls for four medical experiments. In the foreground at right is the control unit for the bicycle egronometer.

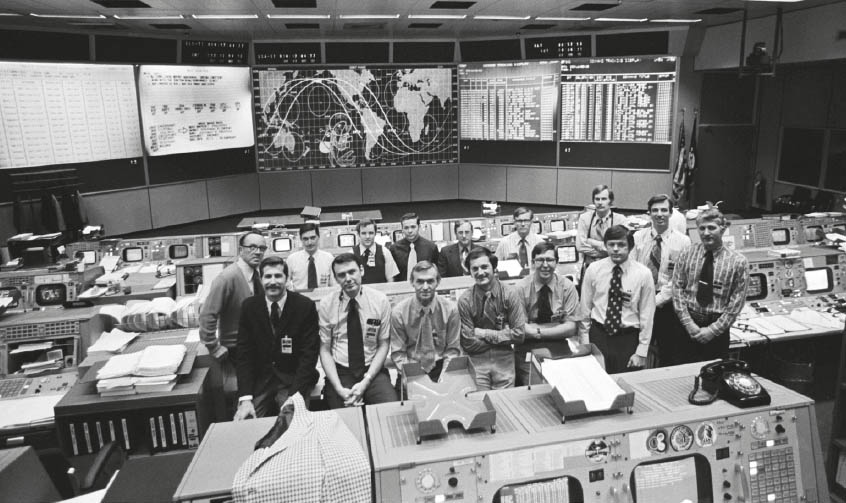

The Skylab 4 flight control team in MOCR 1. Front row, left to right : Tandy Bruce, instrumentation and communications officer; Dick Ramsell, organization and procedures officer; Chuck Lewis, flight director; Sy Liebergot, electrical generation and integrated lighting systems engineer; Ron Lerdal, guidance, navigation, and controls systems engineer; Pete Frank, chief, Flight Control Division; Pat O’Neill, ASCO; and Hank Hartsfield, CAPCOM. Back row, left to right: Bob Gordon, Public Affairs Office; Bob Heselmeyer, biomed experiments officer; Darrell Stamper, Apollo Telescope Mount; Tom Kaiser, flight activities officer; Dr. John Zieglschmid, flight surgeon; John Nelson, corollary experiments; and Earl Thompson, Earth Resources Experiment Package.

Gibson spent hours waiting for solar flares at the ATM Control and Display Console in the MDA. His hand is near the manual pointing control. The empty desk shows that the crew has packed up in the days before reentry. The previous crew brought the hood and new Polaroid SX-70 camera taped to one of the console’s video displays. The camera supplemented the ATM’s limited-magazine cameras—providing lesser-quality but still useful solar corona images—and let the crew compare solar features from one orbit to the next. The electronics in the console, made by Bendix in Teterboro, New Jersey, generated so much heat that the console had its own liquid cooling system.

Pogue dons his pressure suit before his second EVA, on December 25, at the suit-drying station in the forward compartment. The gray hose is looped around the Scientific Airlock, used to expose experiment hardware to space. The workshop had two such airlocks, but the umbrella solar shield had been deployed through one, making it unusable.

Comet Kohoutek was first sighted on March 7, 1973, and was quickly added to Skylab’s observational goals. Although predicted to be dramatic, it apparently partially disintegrated during its swing past the sun in December.

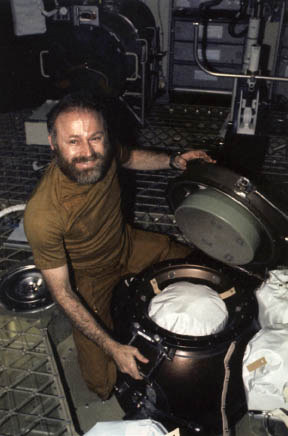

Carr closes the cover to the trash airlock in the center of the crew compartment floor. The brown tabs on the Beta cloth bags fit onto pins to hold each bag in place. The cover was closed and sealed and the compartment depressurized before a lever opened the outer door and a mechanism ejected the bag into the modified S-IVB oxygen tank below.

Pogue’s photo shows Carr flying Experiment M509, the AMU, in the forward dome of the OWS on December 15, 1973. He holds a canister between his legs to evaluate how the unit performed with an object that moved the center of gravity. The CAPCOM was Bruce McCandless, who would go on to fly the first untethered MMU during a 1984 Space Shuttle mission.

The OWS, photographed from the Skylab 4 CM during the final fly-around inspection on February 8, 1974. The ATM’s solar arrays provided about half of the OWS’s electrical power.

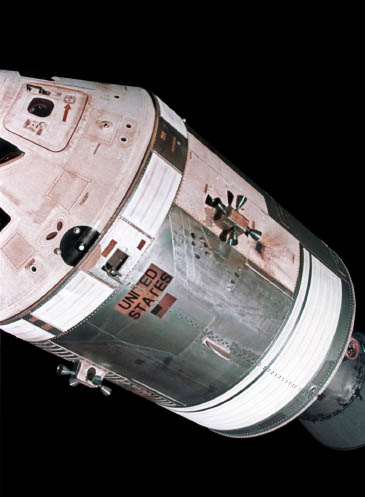

The CSM docked with the OWS, as photographed by Carr during the final Skylab EVA on February 3, 1974, four days before splashdown. During the EVA, which lasted five hours and twenty minutes, Carr and Gibson retrieved material samples and the ATM film canisters, and tested a clothesline-like device for moving equipment.

Carr’s umbilical stretches toward Gibson in this February 3 EVA photo by Carr. Gibson, his feet near the top edge of the Fixed Airlock Shroud, has egressed from the EVA hatch. He holds a lower ATM strut. The ATM is behind him and the MDA is above his head at left. A small discone antenna extends on a boom at top center.

Divers wait with Skylab 4 shortly after splashdown in the Pacific Ocean, 176 miles southwest of San Diego, California, at 8:17 a.m. (PDT) on February 8, 1974. They are three and a half miles from USS New Orleans . It was the first manned splashdown not to be televised live by the three TV networks since Gemini VI, which had the first live television splashdown coverage (previously such broadcasts had not been possible).

Divers wait with Skylab 4 shortly after splashdown in the Pacific Ocean, 176 miles southwest of San Diego, California, at 8:17 a.m. (PDT) on February 8, 1974. They are three and a half miles from USS New Orleans . It was the first manned splashdown not to be televised live by the three TV networks since Gemini VI, which had the first live television splashdown coverage (previously such broadcasts had not been possible).

Gibson prepares to egress from the CM aboard the New Orleans . “I never knew I weighed so much,” he remarked. All three crewmen were deemed to be in good health, and all managed to walk a short distance.

President Richard Nixon presents Pogue with the NASA Distinguished Service Medal before a speech to some five thousand JSC employees and visitors. All three crewmen were thus honored. Nixon also toured displays on the upcoming ASTP mission.

Carr waves as the crewmen prepare to head to Houston after a brief dockside welcoming ceremony in San Diego on February 10, 1974. Three thousand people attended the ceremony.

Carr addresses KSC workers in the VAB on April 19, 1974, during the ceremony for the Skylab 4 crew return and KSC Skylab awards. Behind him are NASA Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight Dale Myers, NASA Deputy Administrator George Low, and NASA Administrator James Fletcher. (photo by John de Bry)