With the poise she brought to essaying the Bibi in mid-1962 [in Guru Dutt’s Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam], Meena Kumari reached her apogee as a tragedienne in clinching her third Filmfare Best Actress award … Yet let us not forget that it was with the ethereal aid of Geeta Dutt’s distinctive vocalizing that Meena Kumari was so viewed to perform the Bibi feat.

I have often wondered about the beauty and diversity of music in our cinema. Picture Raj Kapoor in the recording studio with his music ‘take’ that was so radically different as to make it ring in your ears as the ultimate in cinematics. Having heard Goldie Vijay Anand talking on making and taking music, I felt that I was getting the essence of it all from the true master’s lips. Raj Khosla made no secret of how he learnt all his song-taking from Guru Dutt, but absorbed it so well as to invest it with his personal touch. In a newer school, writer-director Gulzar displayed a different cine outlook altogether, controlling his ultra-cute mode of song-taking through his own screenplay, then bringing his own form and feeling to R. D. Burman’s tunes with his own facile pen. I have thus heard them all, seen them all.

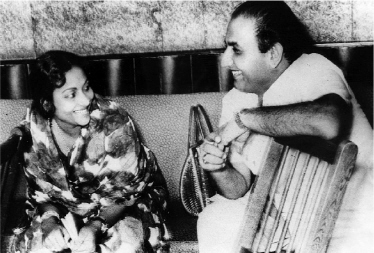

I still remember that beautiful, cool, breezy evening, some time in the first week of October 1964, when I met up with Guru Dutt in his Peddar Road Marble Arch apartment– an evening etched in my mind to this day. For that evening I heard Guru Dutt, first hand, holding forth, with rare passion, about cinema and the role of music in enhancing its effect. Upon hearing Guru Dutt, upon percipiently grasping how he mentally made music before getting around to taking it, I sat spellbound. The man fluidly had music running in his veins. On the style and technique of doing music for movies, Guru Dutt came through as a sheer marvel. He was a revelation in the resonances that an ultra-imaginative director could bring to song-taking as a near art form. That cozy evening he could not have sounded more positive. In fact, from Marble Arch, I had come away, feeling musically illuminated. But what happened to Guru Dutt after such an enriching experience had me reflecting about that cineaste’s having this aptitude, overnight, to turn totally negative. What a crying shame, therefore, that Guru Dutt should have been so eloquent on the theme one evening and the next thing I get to hear is that he is gone, following an overdose of sleeping pills. Taking all those ‘taking’ skills with him.

Guru Dutt’s thirst for life, death alone could quench. Alcohol, in a sense, is a perennial problem in big bad Bollywood. But Guru Dutt’s problem lay elsewhere. The first to tell me something definite about it –I had, till then, only heard about it –was the one who had seen Guru Dutt growing in front of her eyes from his formative 1950–51 Baazi days at Navketan. This was Uma Anand, by then long separated from Chetan Anand. Uma was no gossip; in fact, she figures among the most genuine ladies I encountered in my life. She spoke out of sincere concern for Guru Dutt as still her Navketan boy, as still one of the great hopes of Hindustani cinema. Uma Anand went into details about how Guru Dutt’s escape mechanism came by a circuitous route through West Bengal. About how, when the thing was delayed in its winding transit to Bombay, Guru Dutt Shivshankar Padukone would fly into an uncontrollable rage. That would create immense problems for wife Geeta Dutt who, saddled with their three kids, was still absolutely stable herself–who, in fact, was endeavouring to put her sadly interrupted singing career back on track.

For her part, Geeta Dutt had never taken to Waheeda Rehman. Even if, with a touch of supreme irony, it was Geeta’s inimitable style of singing that had witnessed Waheeda Rehman arriving as a heroine (in February 1957) opposite Guru Dutt in Pyaasa. As the true pro, Geeta had not shied away –not until September 1959 anyway –from feelingly rendering, on Waheeda (through two sides of one N52971 Kaagaz Ke Phool record), Waqt ne kiyaa kyaa hansee sitam and Ek do teen chaar aur paanch–both Kaifi Azmi-written, S. D. Burman-tuned. Kaagaz Ke Phool –as a frozen moment in our mindframe in terms of the film’s being the total cinematic testimony to the each-otherness of Guru Dutt and Waheeda Rehman–just would not work the way this serene pair’s Pyaasa had done. Kaagaz Ke Phool’s tragic box-office fate brought in untold hard times on the Dutt family. Once the debts accumulated came the real Geeta–Guru showdown. Yet Waheeda had remained steadfast in her Guru Dutt addiction as Chaudhwin Ka Chand (by June 1960) came as the Kaagaz Ke Phool offsetter. Wrote Waheeda of her Guru under her own byline: ‘He was a great lover.’

Came, by mid-1962, Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, one more classic turning out to be yet another Guru Dutt Films commercial disaster. The film itself was sheer class. So much so that it won a ‘Best Motion Picture’ nomination for the Silver Bear, as India’s official entry at the 13th Berlin International Film Festival, which Waheeda and Guru attended together in June 1963, nearly a year after the movie sank at the box office. Its complex theme resulted in the film’s failing to register on those who mattered at Berlin. The jury just could not understand why a woman (Meena Kumari) should take to drinking to keep her husband (Rehman) at home! Or why her eldest zamindar brother-in-law (Sapru) should be going to the extent of ordaining her murder–for the ‘insignificant’ reason of her (Meena Kumari’s) being seen in the company of another man (Guru Dutt as Bhootnath)! It was felt that Meena Kumari overacted right through. As for Waheeda Rehman (playing Jaba here), she was on her own Berlin trip, with something else on her mind. She, for her own reasons, had decided–conclusively yet gracefully–to banish Guru Dutt from her life. The last thing Waheeda wanted was a scene, off the sets, in India. She thus waited until the two were in Berlin, where she finally chose to tell her Guru, most emphatically, that they were through–Tum jo huuey mere hamsafar rastey badal gaye… (12 O’Clock, April 1958)–a development which even Geeta Dutt had not anticipated.

Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam’s outright rejection, coupled with Waheeda’s royal rebuff, dealt a body blow to Guru Dutt. If ‘a great lover’ in Waheeda’s eyes, he was a poor loser, as Berlin was to demonstrate. The redoubtable B. R. Chopra pulled no punches as he told me: ‘That man, Guru Dutt, drank all the way back from Berlin to Bombay while keeping all to himself in a corner seat. We knew all about Waheeda having told him, pointblank, that she had made up her mind about him and that was it. She also, discreetly, left Guru Dutt to find his own way back. Guru Dutt was clearly heading towards turning into a mental and physical wreck. I instinctively knew that it was the beginning of the end. What a way for such a creative person to go.’

During that to-prove-fatal evening, Guru had rung Geeta, requesting that their daughter be sent to Marble Arch. Geeta had gently explained why she was turning down the request, logically reasoning that the hour was too late for their daughter to go over from Bandra to Marble Arch. Geeta Dutt, by the last quarter of 1964, was in the process of staging a gallant rearguard action in an attempt to re-create herself as a top playback performer, following the high success of her singing for ‘Chhoti Bahu’ Meena Kumari in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam. Guru Dutt’s sad demise, therefore, left Geeta in the middle of nowhere. Her Guru was but 39 at the time, she had three kids and a reviving performing platform to look forward to, when destiny intervened in a manner shattering as shattering could be.

Bhanwra badaa nadaan haay … Central to Waheeda Rehman–Guru Dutt’s life and times was their attending together, for the screening of Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, the June 1963 Berlin International Film Festival. Here, ironically, is where Waheeda finally said ‘No’ to her Guru

For all that, not for a moment could it be suggested that Guru Dutt was anything but a superlative film-maker. His Kaagaz Ke Phool is proof positive of his world cinematic vision. Yet, even amidst the total mood-movie atmosphere prevailing in Kaagaz Ke Phool, the San-san-san woh chalee hawaa and O Peter O Brother.… Hum tum jise kehtaa hai shaadee numbers rankle –as a blot on Guru Dutt’s reputation as the song-taker without peer in our cinema. I could only presume that Guru Dutt was not his evening-Marble Arch self while picturizing these two numbers– tunes clearly below the Sachin Dev Burman standard as okayed by him.

Let us get down to musical brass tacks as far the Guru–Geeta Dutt connection goes. It is my firm belief that just no one stops to think of how wife Geeta Dutt, in the grand sum, sacrificed a flourishing singing career–while rating second only to Lata Mangeshkar–in the heartburn process of losing her husband to Waheeda Rehman. Do please remember one vital point –that barring the case of the June 1952 Geeta Bali–Dev Anand starrer Jaal (with its Lata quartet of Pighlaa hai sonaa; Choree-choree meree galee aanaa hai buraa; Kaisee yeh jaagee agan; and Chaandnee raatein pyaar kee baatein) –it always was Geeta Dutt working the vocal oracle for her Guru. In each one of his first 10 films barring Jaal–the other nine being Baazi (1951), Baaz (1953), Aar Paar (1954), Mr & Mrs 55 (coming in April of that year), C.I.D. (1956), Sailaab (1956), Pyaasa (1957), 12 O’Clock (1958) and Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959)–Guru Dutt, all through, readily had his blithe-spirit wife, Geeta, to vivify his admittedly unique style of song-taking. Even in the 1952 Lata-dominated Jaal, is not Geeta, too, very much there on Geeta Bali via Soch samajh kar dil ko lagaana and De bhee chuke hum dil nazraana (that hummable duet with Kishore Kumar)?

Against such a consistently Dutt diva-delivering backdrop, one felt saddened to find composer Ravi acquiescing, sheepishly, in the Waheeda-obsessed Guru’s loaded suggestion to sideline Geeta after just one 1959 Chaudhwin Ka Chand recording –executed well enough by our proven performer as Baalam se milnaa hogaa sharmaane ke din aaye. Such arbitrary rejection following a single recording came when Geeta (as a singer) had lost out, not only to Lata, but also to Asha, following her pet composer, O. P. Nayyar, having all but marginalized her. Against such odds, imagine, both Geetas (Bali and Dutt) could–as late as the first half of 1958–fit, Baazi style, into sultry sirenish nightclub surroundings, for us to get, twice inside three months, the Hello Mister how do you do line of tuning from O. P. Nayyar. First, we got guest-role player Geeta Bali swaying (with Ragini’s hero Shammi Kapoor watching) to the vamping vocals of Geeta Dutt –Chandaa chaandnee mein jab chamke (in Mujrim, February 1958 after Geeta and Shammi wed). Next, we got the same Geeta (via the same OP) going, forever, on hepcat Helen as Meraa naam Chin-Chin-Choo (in Howrah Bridge, May 1958). That is how we got to view Meraa naam Chin-Chin-Choo emerging, inexplicably, as Geeta Dutt’s swan solo for OP. In such a setting, Hemant Kumar being her Jai Jagdish Hare contemporary from Anandmath (1952) down, Geeta Dutt clearly looked up to this senior composer-singer to resurrect her, as one of our top voices, via Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, a Bimal Mitra theme, right up her vocal alley, launched as 1959 drew to an end. Guru Dutt had specially summoned Hemant Kumar to score Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam as a musician ethnically suited to the classic theme.

Aaj sajan mohe ang lagaa lo … Geeta Dutt

On his part Hemant Kumar plainly told Guru Dutt that it had to be only Geeta performing playback on Bibi Meena Kumari. With the poise she brought to essaying the Bibi in mid-1962, Meena Kumari reached her apogee as a tragedienne in clinching her third Filmfare Best Actress award for this show. Yet let us not forget that it was with the ethereal aid of Geeta Dutt’s distinctive vocalizing that Meena Kumari was so viewed to perform the Bibi feat. Who but the super Geeta Dutt could have brought the aural aura she did, here, to Na jaao saiyyan chhuda ke baiyaan and Piya aeso jiyaa mein samay gayo re, following the eerie impact she made with Kahein door se awaaz de chale aao?

Hemant Kumar, as an established voice himself, significantly consigned Asha Bhosle (in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam) to second-lead vocalizing on Waheeda Rehman as Jaba –Meree baat rahee mere man mein and Bhanwra badaa naadaan haay. This without in any way preventing Asha from attaining a new vocal high with her terrific ‘atmospheric’ renditions of Saaqeeyaa aaj mujhe neend nahein aayegee and Meree jaan O meree jaan achcha nahein itnaa sitam. For all that, on the all-important visage of Meena Kumari as the Bibi, Hemant Kumar would not compromise in the matter of its being the voice of Geeta Dutt. By way of a sincere thank-you, regally did Geeta do the vocal trick on Meena –the exact way, over a decade earlier, she had worked the 1950 Meera musical miracle on Nargis playing Jogan.

In this context, I made it a musical point to ask Guru Dutt why he had scrapped the ear-holding Hemant Kumar solo, Saahil kee taraf kashtee le chal, from that climax scene of Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam. Guru Dutt’s rejoinder: ‘The censors just wouldn’t entertain the idea of the Hindu Bibi lolling in the lowly Ghulam’s lap during that horse-carriage ride. I was thus compelled to delete Hemant Kumar’s rich Saahil kee taraf vocals filling the background.’ What a sonorous missout for viewers! Hemant Kumar himself was so proud of his Saahil ki taraf composition and rendition that, four years later, he chose to replicate it as Ya dil kee suno duniyaa waalon on Dharmendra in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Anupama, the 1966 theme so memorably scored by this Bengal ace.

By the time Guru Dutt decided so sadly to end his life (during the night of 9–10 October 1964), Geeta found herself heading towards becoming a mental agonizer all the way. Yet Geeta Dutt left the scene as a 1972 Tanuja Anubhav to remember via Koee chup ke se aa ke sapnen sulaa ke mujhe jagaa ke; Meree jaan mujhe jaan na kaho; and Meraa dil jo meraa hotaa. This very special Geeta effect is what Asha Bhosle strove, all along the line, to match, getting as close as Sachch huue sapnen tere on who but Waheeda Rehman in Kala Bazar (1960)! But Geeta, as we saw, unexpectedly stole Asha’ smonsoon thunder even here with Rimjhim ke taraane leke aayee barsaat!Geeta Dutt, upon being contacted forrendering this delicious duet with Mohammed Rafi, created a stir by insisting that she would not sing it if the number went, live, on femme fatale Waheeda! Sachin Dev Burman still wanted this blues-chasing performer alone to render the monsoon duet with Rafi.

Kala Bazar writer-director Goldie Vijay Anand, happily, went along with his pet composer in the matter. Thus Dada and Goldie agreed that the Rimjhim duet –if compulsively required to be merely ‘voiced over’ on Waheeda Rehman and Dev Anand–needed Geeta Dutt’s ultra-bright vocals for it to come off. That is how you have Rimjhim ke taraane le ke aayee barsaat descending as a veritable shower of melody from the Kala Bazar background. Geeta, remember, had not taken kindly to her summary playback sacking from Chaudhwin Ka Chand, after just one song rendition. She thus had a Chaudhwin Ka Chand score to settle with Waheeda. Settle it in style did Geeta Dutt via Rimjhim ke taraane le ke aayee barsaat.

By February 1960, there was not a day during which Guru Dutt did not stomp out of their Pali Hill home in a temper. Things had really soured between the lovely Geeta and ‘Hamlet’ Guru, once the wife divined that Gouri–in Bengali and English with her in the title role (the character played by Shamim in the Kidar Sharma 1943 Ranjit original titled Gauri) –was a grandiosely 1958-announced movie never quite intended to come off. Geeta saw through this so-called Cinema Scope offering as a Guru sop to buy momentary peace with her on the Waheeda front. Gouri, in fact, had music buffs wondering how tellingly Geeta would emerge as a singing-star, vocalizing for the fledgling R. D. Burman. But, as her Guru okayed a tune for Gouri, only predictably to reject it later, Geeta forlornly discerned that the chances of her performing on the silver screen, for S. D. Burman’s son Pancham as well, were next to nil.

Being Dada Burman’s chief assistant on Pyaasa, Pancham had been a fascinated ear-witness to the virtuosity that Geeta had brought to the Aaj sajan mohe ang lagaa lo happening. In a signed article, Geeta Dutt had even pinpointed this number as rating among her ‘Ten All Time Bests’. Geeta underscored the point by describing Aaj sajan as ‘an outstanding keertan composed by S. D. Burman’. All keyed up to perform for RD, therefore, was Geeta as Gouri. But, as Gouri stood jettisoned, Geeta realized, with a pang, that she had sacrificed a genuinely thriving singing career in vain for her Guru. The marriage had never really worked from the moment Waheeda came into Pyaasa Guru Dutt’s life, near mockingly, with Jaane kyaa tuu ne kahee! This Dutt-diva vocal interpretation had O. P. Nayyar–introduced to Guru by Geeta–publicly praising Jaane kyaa tuu ne kahee as an ultra-dainty Geeta rendition of an ultra-dainty S. D. Burman composition.

Was O. P. Nayyar Asha-pro from the word go? Let me quote OP himself to underpin how much he once cared for Geeta Roy Dutt, as he wrote on ‘My Ten Bests’ till end-1956: ‘One of my top favourites is Geeta–Rafi’s Yahaan hum wahaan tum from Shrimati 420 [1956]. The mukhda is my wife Saroj Mohini’s and I have been much complimented upon the tapering music of the words –Bolonkahaan ajee yahaan.’ Indeed, O. P. Nayyar goes on to place, at No. 1, among his Ten Bests till then, Geeta–Rafi’s Yeh hai Bambai meree jaan (on Kum Kum-Johnny Walker) in C.I.D., noting how ‘it has been my best-selling record so far’. Which are the other Geeta–Rafi duets making it to this prize O. P. Nayyar listing till end-1956? Udhar tum haseen ho idhar dil jawaan hai, filmed on Madhubala-Guru Dutt in Mr & Mrs 55, and Ghareeb jaan ke, picturized on Anita Guha-Johnny Walker in M. Sadiq’s Chhoomantar (1956).

Are there, then, no Geeta solos in OP’s favourite picks? Of course there are –Geeta’s Zaraa saamne aa zaraa aankh milaa from Baaz (1953) –the film originally announced as to be scored by S. D. Burman. In fact, OP identified it as ‘one of my best compositions’ as enacted by the peerless Geeta Bali mockingly seducing Guru Dutt in Baaz. Also in the O P Ten Best-list is that smart Nayyar solo only Geeta Roy could have lit up for this trackblazer –Yeh lo main haaree piyaa, going on Shyama in Guru Dutt’s Aar Paar (1954). ‘Even now, after my rapid rise,’ wrote OP, ‘I encounter producers who ask: “Don’t you think this tune’s too jazzy?” When I say it isn’t, they withdraw their objection but remain sceptical!’ concluded the originator of the Binaca Geetmala signature-tune: Pon-pon-pon baaje baajaa dholak dhin-dhin-dhin–so infectiously put over by Geeta Roy in O. P. Nayyar’s 1952 debut film, Aasman. From those early days, the imperturbable Geeta Roy, unlike the reticent Lata Mangeshkar, entertained no fear of being vocally bested in a tandem rendition by her male counterpart. Take that super Sailaab tandem composed by her brother, Mukul Roy, and unfolding (as written by Majrooh Sultanpuri) as Hai yeh duniyaa kaun see ae dil mujhe kyaa ho gayaa. At first, there was only the Hemant Kumar-rendered edition of this Hai yeh duniyaa kaun see tandem –on Abhi Bhattacharya in the Guru Dutt-directed Sailaab (January 1956). Only as a Guru Dutt directorial afterthought, a full two years after the Hemant recording had taken place, did Geeta Dutt come into the Sailaab picture –on Geeta Bali as Hai yeh duniyaa kaun see. Do vocally absorb how Geeta Dutt brings her own distinct tandem nuancing to Hai yeh duniyaa kaun see –in no way deterred by Hemant Kumar’s resonant rendition of such a balmy composition.

Where Lata never could totally conquer her dread of the male singer’s finishing one up on her in a tandem rendition, Geeta Dutt scored, in her own inimitable style, the moment she came to render the competing number. In fact, Geeta did not view the male singer, here, as competition at all! This indeed was one specialist area of rendition in which Lata truly envied Geeta. Wonder how Geeta Dutt would have treated the tandem if we could, conceivably, picture her as agreeing to put over Na tum humein jaano on her bête noire, Waheeda Rehman, in Baat Ek Raat Ki–coming in the same 1962 year as Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam. The 1962 year by which S. D. Burman had pronounced Hemant Kumar’s vocals to be ‘deteriorating’ and yet had that singer, so feelingly, going on Dev Anand as Na tum humein jaano! A similarly ‘vocally deteriorating’ Geeta, be certain, would have rendered Na tum humein jaano, like no one else could, on Waheeda Rehman –exemplarily as Suman Kalyanpur might have been discovered to be giving expression to her side of the memorable Baat Ek Raat Ki tandem.

After all, O. P. Nayyar, as compared to Geeta, was already beginning (by early-1957) to lean towards Asha, as he initially rejected Ved-Madan’s Johnny Walker, a film starring (with Shyama) the performer answering to that brand name. When Ved-Madan persisted in venturing to get OP to score such an intoxicating theme, Nayyar, as a mere lark, said he would do Johnny Walker if the duo produced the latest, in Cadillac limousines, as his spot fee. Lo and behold, there was a brand-new Cadillac (then costing Rs 95,000) parked outside OP’s Marine Drive ‘A’ Road ‘Sharda’ building, first thing the following morning! That left OP with no scope to drive any further bargain, so he summoned Geeta to record, with his neo-favourite Asha for Johnny Walker (1957), Thandee thandee hawaa poochche unkaa pataa and Jhukee jhukee pyaar kee nazar dekhein unhein dil mein jhoomkar. Both numbers proved instant Binaca Geetmala slot-finders, both came to be written by Hasrat Jaipuri.

Udhar tum haseen ho …Geeta-Rafi dueting winsomely was crucial to the

earlier genre of Guru Dutt films, among them Mr & Mrs 55

Could it then be that Waheeda vibed so well with Guru Dutt –as a peer-person of restraint and reserve like her –while the bindaas Geeta was into pursuing a more open career built upon her unique singing style? Built upon her persona’s being ever so full of the joy of living, as reflected on the shapely Shakila, in Aar Paar, via Hoon abhee main jawaan ae dil? Even Hoon abhee main jawaan is but one facet of Geeta’s multi-hued singing presence. Another fascinating facet is her vocal courage in agreeing to soliloquize that O. P. Nayyar private classic, the C. H. Atma-immortalized Preetam aan milo, as a background solo–‘voiced over’ on a downcast Madhubala (essaying Anita with a rare flair opposite Guru Dutt as Preetam)–in Mr & Mrs 55. Such was the ‘private’ Lahore impact left by C. H. Atma via O. P. Nayyar that no female singer, save the totally uninhibited Geeta Dutt, would have braved trying to re-create, on the silver screen, such a cult rendition –till then to be heard only on a gramophone record. Geeta felt a female edition of Preetam aan milo would be her mode of showing appreciation for the way Saroj Mohini had written the number with her Lahore lover, Omkar Prasad Nayyar, in her mind and heart. In this light, Geeta ventured, vocally, to give Preetam aan milo all she had–as an OP composition for his Mohini. Geeta always did think the world of OP as a composer. It was, in fact, Geeta who had told Guru Dutt that ‘OP composes feelings, not words’. Geeta reached such a ‘feeling’ conclusion after having vocalized, for OP, Ae dil-edeewaana aag lagaa lee kyon daaman mein o zaalim on Geeta Bali in Guru Dutt’s Baaz (1953). It is easy to dismiss Geeta–Rafi’s 1954 dueting, Sun sun sun sun zaalimaa on Shyama-Guru Dutt, as an OP ‘Western copy’, carried out at the behest of Aar Paar maker Guru Dutt. But just reflect upon the aptitude with which the same OP had tuned the same Majrooh Sultanpuri, in the same Aar Paar, to go on Shyama via a Geeta, so heart-stoppingly, mood-swinging and mood-singing it as

Jaa jaa jaa jaa bewafaa

Kaisaa pyaar kaisee preet re

Tuu na kisee ka meet re

Jhoot tere pyaar kee qasam

Jaa jaa jaa jaa bewafaa…