A hefty, white sharkskin-suited gentleman measuring up, in every single detail, to the specification of ‘tall and well built’– the way the petite Lata fancied her ideal man to be in her salad days as a singer – C. Ramchandra was undoubtedly a dam bursting with talent. A look at his career graph makes an interesting read, evoking endlesss memories, emotions, nostalgia and the romance of a bygone era, all in the same tuneful breath.

Matching Lata Mangeshkar’s vocals with his tuning, all over again, was C. Ramchandra, preparing for the special 1963 Republic Day performance. Yet was it Lata and the Kavi Pradeep-penned Ae mere watan ke logon, all the way, in front of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru? No way. Prestigiously preceding her on that New Delhi podium–at a point when the 1964 Leader number on Dilip Kumar had yet to find public release –was Mohammed Rafi, soulfully rendering Apnee azaadee ko hum hargiz mitaa sakte nahein with Naushad and his orchestra in exemplary attendance. But the rendition failed –for whatever reason – to register quite the way it was expected to do on that Delhi audience. Lata’s Ae mere watan ke logon emerged as a happening in which our wraith like chanteuse came to be embraced, by Jawaharlal Nehru, as the one who had brought tears to his eyes. Following this the Lata–Rafi royalty confrontation got even sharper.

Kavi Pradeep was not present to witness the ‘Delhi show’ for he had not been invited –a sad reflection on the insensitive powers that were. If one were to add up the points on the nation’s song-filled graph – through 63 years of India’s Independence–it is Kavi Pradeep’s patriotic chartbusting you get to view. From Door haton door haton door haton ae duniyaa waalon Hindustan hamaara hai (Kismet, 1943) to Dekh tere sansaar kee haalat kyaa ho gayee Bhagwan (Nastik,1954) to Aao bachchon tumhein dikhaye jhaankee Hindustan kee is mittee se tilak karon yeh dhartee hai balidaan kee…Vandemataram Vandemataram (Jagriti, 1955), it is Kavi Pradeep’s name that is synonymous with inspirational numbers on the silver screen. Even off-screen, it is, to this day, the Pradeep hymn Ae mere watan ke logon that touches the nation’s imagination. It is Kavi Pradeep’s idiom of expression that remains a happening with which today’s young tune as instinctively as do we vintage listeners.

Few know that C. Ramchandra had actually tuned Ae mere watan ke logon as a duet, for Asha Bhosle to begin it as Aemere watan ke logon, for Lata to take it up as Zaraa aankh mein bhar lo paanee. Snag –Lata and C. Ramchandra were not on talking terms by then! Kavi Pradeep played master reconciler, by shrewdly surmising C. Ramchandra to be still sweet on Lata, if he could get her to attune with the composer afresh. This coincidentally was when Lata, out of the blue, called around six one morning at Pradeep’s Vile Parle home to express her keenness on singing Ae mere watan ke logon, provided she could do it as a solo! Pradeep found C. Ramchandra, too, to be jumping at this chance to have his very own Lata back to render such a hallmark number. Forgotten, in a trice, were C. Ramchandra’s long-spread rehearsals for the number with Asha Bhosle.

Pradeep, a Bombay Talkies singer-composer in his own right, already had a Lata-suiting tune to go with what he had already written. But C. Ramchandra felt that though the tune sounded great it was not one with which the lay audience in Delhi could be expected to vibe on the spot. Thus, finally, the high Ae mere watan ke logon tum khoob lagao naara … note–the chhand with which Lata begins the invocation as we hear it today–is that original Pradeep tune. The simpler, faster stanza you hear –after that high is attained by Lata–is Ae mere watan ke logon as modified by C. Ramchandra for instant public approval. Rest is history. Everyone acted the moment Jawaharlal Nehru reacted. The minute Nehru got up to hug Lata, the state machinery swung into motion. The master tape was rushed to All India Radio’s Vividh Bharati–for instant countrywide projection on its National hook-up. In ‘record’ time, HMV (the Gramophone Company of India), too, had Ae mere watan ke logon arriving in the market. The Pradeepian sentiment had touched the national gut, acting as a balm to a people traumatized by the October 1962 Chinese military assault on India’s borders. One had to be part of the ‘feeling-defeated’ mood –then seizing India as a nation –to comprehend the extent to which Lata’s empathetic rendition captured the prevailing mood.

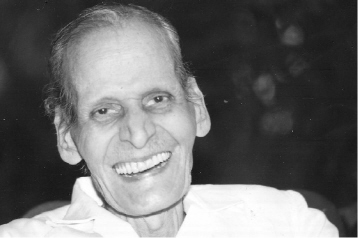

Kavi Pradeep: made Ae mere watan ke logon Lata-happen

A question repeatedly asked to this day is: ‘Did Lata then play fair in hijacking (from Asha) a song destined to create, for the Mangeshkar diva, a rare niche in the nation’s psyche?’ Or was it merely a case of Lata’s marginalizing Asha in sisterly singing rivalry? Never forget that Ae mere watan ke logon came to be rendered by Lata –alone –after New Delhi, discreetly, let it be known, at the last minute, that it wanted only our ‘nightingale on the highest branch’ performing before Prime Minister Nehru. Ae mere watan ke logon thus marks a watershed in contributing substantially to Lata’s standing as ‘A Tuneful Symbol of National Integration’ (in the words of Dr Chintaman Dwarkanath Deshmukh, the first Indian to be appointed as Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, an eminent educationist who later served as a key minister in Nehru’s cabinet). The word ‘National’ (in ‘A Tuneful Symbol of National Integration’) was a happy afterthought on the part of Dr C. D. Deshmukh who, at first, had identified Lata, more briefly, as ‘A Tuneful Symbol of Integration’ at South Bombay’s Rang Bhavan during her silver jubilee celebration (April 1967). Through the years, no matter where, when and why Lata put over Ae mere watan ke logon, she unfailingly mentioned Kavi Pradeep as its author. But never C. Ramchandra as its creator! Even Dilip Kumar –viewed to be on the same mutual admiration society stage as Lata–opted always to credit Pradeep, but never C. Ramchandra.

A hefty, white-sharkskin suited gentleman measuring up, in every single detail, to the specification of ‘tall and well built’–the way the petite Lata fancied her ideal man to be in her salad days as a singer – C. Ramchandra was undoubtedly a dam bursting with talent. A look at his career graph makes an interesting read, evoking endless memories, emotions, nostalgia and the romance of a bygone era, all in the same tuneful breath. The ‘tall and well-built’ specification, as laid down, is going by the vicarious word of Shamshad Begum whom Lata so sensationally superseded as C. Ramchandra’s main singer. If Lata-C. Ramchandra did come together, afresh, to collaborate on Ae mere watan ke logon, the feeling of being tunefully together, again, did not last too long. C. Ramchandra rationalized their final break in those famous words: ‘Don’t you know, when we Maharashtrians quarrel, we quarrel for a lifetime?’

A life-and-times listening experience it had been for us viewers as Arati Mukherjee and Mahendra Kapoor were set to be adjudged as winners of the Metro–Murphy Singing Contest in the open-air maidan adjoining the Mahalaxmi Race Course during a cool January 1957 evening, when all eyes were on the galaxy of judges. That our ghazal mastermind-to-be was the juniormost among that judging fraternity (of Anil Biswas, Naushad, C. Ramchandra, Vasant Desai and Madan Mohan) is a telltale pointer to the calibre of composers turning the 1951–60 decade into the golden era of Hindustani film music. The most daringly Westernized, musically speaking, among the five was C. Ramchandra, who shared with Naushad the distinction of turning every other film he did into a silver jubilee hit. Among his earliest jubilee landmarks (sans Lata) is Filmistan’s Shehnai (1947), witnessing Chitalkar Ramchandra taking the nation by storm with his Aanaa meree jaan meree jaan Sunday ke Sunday rhythm, prompting Gulshan Mehta (Ewing) to launch a column styled Sunday Ke Sunday by ‘Meri Jaan’ in D. F. Karaka’ sweekly newspaper Current. C. Ramchandra, answering to the name of Chitalkar as a playback performer, rambunctiously sang the all-values-challenging Sunday ke Sunday, as a two-sided (N26963) number written by the impish Pyare Lal Santoshi. The traditional rural segment was rendered by him with Meena Kapur and the saucy upmarket flip-side with Shamshad Begum. Followed Khidki (1948) with its leitmotif of Qismat hamaare saath hai jalne waale jalaa karein, the (GE8088) foot-tapper affirming C. Ramchandra as the trendsetter for all seasons. Thereafter, the man never looked back. Whether it be Gore gore o baanke chhore (from Samadhi, 1950); or Yaara wai-wai yaara wai-wai (from Sargam, 1950); or Baabdee boobdee bam bam bam (from Khazana, 1951); or Apalam chapalam (from Azaad, 1955), he blazed the boldly Westernized orchestral trail for first Shanker-Jaikishan and then O. P. Nayyar to follow. A composing wizard was C. Ramchandra, his range, in Albela (1951), extending from Dheere se aa jaa ree to Bholee soorat dil ke khote. One still remembers how, at the end of that January 1957 Metro–Murphy Contest, C. Ramchandra suddenly surfaced, centrestage, with his full orchestra–to have Asha Bhosle performing live, under his baton, the first-ever rock-’n’-roll number in the ‘discography’ of Hindustani cinema. Asha Bhosle brought down the Mahalaxmi house that evening with her ultra-spirited rendition of Mr Jaan ya Babakhan ya Lala Roshandaan from Nutan–Dev Anand’s Baarish, all poised for release by February 1957.

The five stalwart judges at the January 1957 Metro–Murphy Contest to

unearth new singers –(L to R): Vasant Desai, Anil Biswas, Naushad,

Madan Mohan and C. Ramchandra

That (just seven months after this) the same C. Ramchandra had Kishore Kumar stealing a march, over such an in-form Asha Bhosle, with Eena meena deeka (in M. V. Raman’s Aasha, 1957) is a testimony to the regard this ever resourceful composer had for our unique singing-star – a KK fit to be hailed as the Danny Kaye of Indian Cinema. ‘Chitalkar’s a first-class composer!’ I had heard the musically erudite S. D. Burman acknowledging when Dada commended C. Ramchandra as the Westernized model to son RD: ‘If you must go modern, Pancham, study the vistas explored by Chitalkar as a composer.’ No wonder there was an uproar when I hailed R. D. Burman as the ‘C. Ramchandra of the 1970s’ in my Filmfare‘On Record’ column. Fans were up in arms, arguing that Pancham was not a patch on the Mr Jaan original! That was then. Today Pancham is recognized as ‘The Jet’ Setter supreme. While C. Ramchandra is a mere name to a generation whose understanding of music extends only from R. D. Burman to A. R. Rahman.

Being in the forthright company of C. Ramchandra was an experience. As our talk (during one of my meetings with him) turned to Kishore Kumar, this master composer re-emphasized: ‘So what if he has no classical background? Teach Kishore something and he picks it up on the spot. In fact, I find him to be actually improving upon what I’ve sung out for him. Kishore’s extra-swift grasp, his vocal flexibility, not one of our male singers can match!’ Thereupon I cut in: ‘What you mean is that only Kishore Kumar (in Aasha) could have brought off Eena meena deeka. Hasn’t Asha Bhosle (going on Vyjayanthimala) matched Kishore–note for Eena meena deeka note–in that 1957 film?’ His reply: ‘No, she hasn’t! If only because Kishore is Kishore, in Eena meena deeka, the way he acts it out on the screen. How Kishore improvised even while rehearsing, as we sang Eena meena deeka together in the recording studio, just before the take. Never ever mention Kishore and Rafi in the same vocal breath!’

I let it go at that. Yet take those two (November 1957) Nausherwan-e-Adil Lata–Rafi dainties –C. Ramchandra-tuned and poetess Parwaiz Shamsi-written–unfolding on Mala Sinha-Raaj Kumar as Bhool jaaye saare gham and Taaron kee zubaan par hai mohabbat kee kahaanee. With what matching feeling does a soz-filled Rafi, here, join Lata! A Lata sounding mellifluous as mellifluous could be under C. Ramchandra’s baton dipped in aam-ras. To think that C. Ramchandra settled for Rafi only because Nausherwan-e-Adil Sohrab Modi (as the Minerva Movietone boss) had decreed that it shall be the vocals of that silver-toned singer on the emperor’s son Naushazd (played by Raaj Kumar in the film). Thus did we get, from the same Rafi–C. Ramchandra singer– composer combo, in the same Nausherwan-e-Adil, the exquisite ghazal on ‘Naushazd’ Raaj Kumar as written by that Persian-oriented poetess Parwaiz Shamsi: Yeh hasrat thhee kee is duniyaa mein bas do kaam kar jaate.

Did C. Ramchandra then have a point when he opined that ‘Rafi took no end of readying for a recording’? No way, it all depends on the equation between the composer and the singer. For Naushad, O. P. Nayyar and Shanker-Jaikishan, Rafi could sing no wrong –once rehearsed for the song. For Anil Biswas, C. Ramchandra and Salil Chowdhury, such repeated rehearsing meant a break on their being freewheeling. S. D. Burman agreed with the Naushad–Nayyar–SJ line of Rafi reasoning, R. D. Burman didn’t. Pancham–à la C. Ramchandra –wanted the freedom to experiment to the end. ‘From the day I cast him in the Raag Pahadi mantle of Suhanee raat dhal chukee in Dulari as we approached the 1950s,’ recalled Naushad, ‘I sensed that my rehearsing Rafi was only part of the scene. Rafi went home with the notations and worked further on the tune, so that he finally came refreshingly taiyyar [ready] for the recording. At this sensitive stage –short of postponing the recording itself to another day –no composer worth the name would suggest a change of tune if he wanted Rafi to be at his resonant best.’

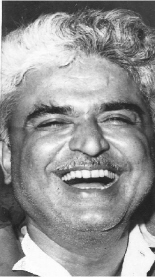

Gore gore –

C. Ramchandra

Naushad owed his unique niche in our cinema to the fact that he could be at once classy and lucky. Much like an ‘Admiral Horatio Nelson handpick’ was Naushad. For example, after all the qualities of a sterling war performer were read out to Admiral Lord Nelson, ‘Is he lucky?’ was the one query the great navigator posed. Naushad had everything, plus he was ‘lucky’! He proved to be mighty lucky for that pedigree composer Roshan when the latter was not just down but also looked to be out. Nasreen Munni Kabir in her Lata Mangeshkar: In Her Own Voice (Roli Books, New Delhi, 2009) has our diva noting: ‘In fact, you won’t believe it, but it was Naushad Sahib who recorded Roshanji’s song, Saari saari raat teri yaad sataye, for Aji Bas Shukriya [1958]. We were at Mehboob Studios and Naushad Sahib arrived. He was such a respected composer and Roshanji had so much regard for him. Roshanji asked Naushad Sahib: “Why don’t you record my song for me today? It will make me happy.” So Naushad Sahib instructed me while I was singing. Of course he didn’t change even a single note of Roshanji’s original composition.’

Conceding Mehboob Studios to be Naushad’s happy hunting ground, how possibly could our ‘Sangeet Samrat’ have arrived there, at such an opportune time, for Roshan? I say that Lata quietly got Naushad there in what must be acknowledged as a tremendous gesture on her part. Roshan was going through the worst phase of his career when – helped along by his family friend Ameen Sayani via Binaca Geetmala – Lata’s rendition of Saaree saaree raat teree yaad sataye (going on Geeta Bali in Aji Bas Shukriya) marked the April 1958 beginning of his comeback. It was a pulp film, still Saaree saaree raat represented the turn of Fortune’s wheel for a Roshan looking a goner.

Come 1960 and Naushad (Mughal-e-Azam) was face to face with Roshan (Barsaat Ki Raat) –these two being top contenders for the Filmfare Best Music award that year! Cold comfort it was for Naushad to know that the prize he came to be so diminishingly denied, for his epic 1960 Mughal-e-Azam score, went to Roshan neither –for Barsaat Ki Raat. Three years later, the same Roshan was once again challenging Naushad’s Sadhana–Rajendra Kumar blockbuster, Mere Mehboob, for the Best Music award –via the ageing Bina Rai–Pradeep Kumar pair’s Taj Mahal! When the 1963 Filmfare statuette finally went to Roshan as his maiden such prize, I met Naushad, who told me that his Mere Mehboob music (with Sadhana looking a vision as lensed by G. Singh) was not any way inferior to Roshan’s Taj Mahal score in a film having, for its heroine, a Bina Rai all set to look Ae maa teree soorat se alag… (the 1965 hit song composed by Roshan for L. V. Prasad’s Dadi Maa in which Bina Rai played an ageing mother). Naushad thus had reason to agonize about his Roshan-magnanimity as ‘Crush your opponent when he is down!’ has been the maxim in this HMV-dog-eating-HMV-dog industry. An industry in which Shanker had no compunction, after SJ’s having already won the 1959 Filmfare Best Music award for Hrishikesh Mukherjee Anari, in pontificating: ‘We should be getting it this year [1960], too, for Dil Apna Aur Preet Parai!’ Having said that, SJ ensured that they clinched the 1960 Best Music award too –at the expense of Naushad’s Mughal-e-Azam, if you please. After his maiden such award in 1953 (for Rafi–Lata’s Tuu Gangaa kee mauj from Baiju Bawra), Naushad had been in contention for the prize in 1954 too. Yet again, not for the full score of M. Sadiq’s Shabab, but for one song in that lavishly mounted film – Chandan ka palnaa resham kee doree, as rendered by Hemant Kumar on a Bharat Bhooshan called upon to put a restless ‘Rajkumari’ Nutan to sleep! This 1954 award Naushad came to lose to S. D. Burman –to Talat Mahmood’s edition of the Taxi Driver tandem, Jaayein toh jaayein kahaan, as picturized on Dev Anand. Would Naushad have posed a stronger threat to S. D. Burman if Hemant Kumar’s maiden (Chandan ka palnaa) rendition, for our Grand Mughal, had been in the voice of Rafi?

Well, it was originally in the voice of Rafi, only the Shakeel Badayuni wording was different. If Hemant Kumar’s Chandan ka palnaa is in Raag Pilu, Rafi’s original (for this Bharat Bhooshan–Nutan Shabab situation) was to have been in Raag Purya Dhanashri and it was penned to come over as: Chalee jaa dheere dheere door/Gagan ke paar hai ek sansaar/Ke jis ka naam thhaa Nindiyapur. … Would Rafi’s singing it this winsome way (in Raag Purya Dhanashri) have excelled the Raag Jaunpuri rendition of Jaayein to jaayein kahaan by Talat Mahmood? Nothing doing, there was no beating Talat at his own ghazal game in 1954 –that is why SD had summoned this crooner for just one song in Taxi Driver! After all, even Hemant Kumar had sung Chandan ka palnaa surpassingly–with just the right measure of ‘feel’ that Naushad wanted–to no award-winning avail. Incidentally, Rafi had not been pleased about losing out on this Shabab theme song, Chandan ka palnaa, after his being initially rehearsed for it as Chalee jaa dheere dheere door. After he had been, otherwise, so distinctively the voice of Bharat Bhooshan through each one of the four songs going on that hero in Shabab. Neither in Shabab (1954) nor in the 1958 Sohni Mahiwal case of yielding Chaand chhupaa aur taare doobe to Mahendra Kapoor did Rafi openly sulk. Naushad told me about how Rafi never would directly protest once it was explained to him that the song only ‘came from the background’ in the voice of Mahendra Kapoor.

The position had been totally different, three years earlier, after Naushad recorded the Uran Khatola (1955) climax number as, not a Raag Durga geet in the shape of O door ke musafir, but as a Raag Bageshri ghazal in the form of Akelaa hum ko chhod ke/Hamaare dil kotod ke/Kahaan chale kahaan chale. There was all-round satisfaction as this Rafi-rendered ghazal appeared to have been okayed by Naushad. Even Dilip Kumar looked mighty pleased with the Rafi rendition. Uran Khatola director S. U. Sunny was floored, therefore, when Naushad told him that he had to re-do the number, since something vital, in terms of dard (melancholia), seemed to be still missing in the end-result. Shakeel’s follow-up lines here –argued Naushad–were not quite blending with the opening ghazal sentiment, as they came over as: Na hogaa jab tumhaara dum/Toh jee ke kyaa karenge hum/Jo tum chale khushee chalee/Bahaar-e-zindagee chalee/Zameen-oaasmaan chale/Akelaa hum ko chhod ke/Hamaare dil ko tod ke/Kahaan chale kahaan chale…

Naushad’s word was musical law those days; even Dilip Kumar had to fall into Akelaa hum ko chhod ke line –out of his inherent respect for the man’s composing judgement. All the more so as Uran Khatola was Naushad’s own co-production with director S. U. Sunny. Naushad later narrated to me how Rafi was the one man who remained superbly unaffected. After everyone else had said his bit did Rafi venture to walk up to his mentor-composer to ask: ‘When do I come home, Naushad Saab, for rehearsing the new tune?’ In fact, when a week later, Rafi came to render it as O door ke musafir–as a geet in Raag Durga–he waited even after Naushad had okayed the take, just in case! To think that such a committed singer was spurned by some top composers when he was so eminently acceptable to such strikingly contrasting musicians as Naushad and O. P. Nayyar. Rafi kept both these composers perennially pleased when neither really cared for the other’s music. In fact, Nayyar looked on forlornly as Naushad reached for the sky with Aan in the very 1952 year in which OP’s Aasman had seen him all but sink with that his maiden movie. If OP did not exactly come to adore Naushad, he certainly admired that mauseeqaar’s robust 1952 challenger, the Rafi-baiting C. Ramchandra. OP, in fact, was all praise for the cutely coquettish cadence that C. Ramchandra had brought to Asha Bhosle’s 1959 vocals, vocals sparkling on neo-vamp (Asha Nadkarni) Vandana–in that heart-stealer so saucily penned by Bharat Vyas for V. Shantaram’s Navrang as:

Aa dil se dil milaa le

Ees dil mein ghar basaa le

O rasiyaa man basiyaa

Aa jaa galey lagaa le

Aa dil se dil milaa le

Aa dil se dil…