As the true faqeer of cinesangeet Aemerewatan ke logontumkhoob lagao, Vasant Desai brought to motion picture art and craft a musical vision extending way beyond the meretricious silver screen. Divine was his touch even as Hindustani cinema wallowed in shimmery mediocrity.

Which one from among Dr Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani (1946), Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje (1955), Do Ankhen Barah Haath (1957) and Goonj Uthi Shehnai (1959) represented the high-water mark of his career? Vasant Desai valued each one of those four milestone movies as his humble contribution to cinema as something more than pop art. Yet the one moment he recollected with rare relish was being specially invited by ‘Sangeet Kalanidhi’ M. S. Subbulakshmi to come down to Madras to compose the tune for a Sanskrit invocation written by the Sankaracharya –something our doyenne had to render when she performed so prestigiously at the United Nations in 1966. MS was so pleased by Vasant Desai’s mode of tuning with her that she presented the musician with a cheque for Rs 500. A fee our composer par excellence flatly refused to accept, saying he had worked, not for the money, but for the honour of interacting with a musician of Ms’s calibre. Finding her insistent, he finally took it, only to frame that cheque as a memento and preserve it, as an MS souvenir, to his dying day. Live for music did Vasant Desai. When Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru lamented the fact that 20 children in our country could not get together to sing the Jana gana mana national anthem correctly, Vasant Desai felt it deeply. His early-60s response was to gather 50,000 school children to sing Jana gana mana in front of Pt. Nehru at Mumbai’s Shivaji Park.

Children of India banding together to sing it in unison was his underlying aim in composing Hum ko man kee shaktee denaa for first-timer Vani Jairam to render on a Jaya Bhaduri 1971-debuting as Guddi in a school uniform. But the film’s illustrious maker, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, was ultra-keen upon using, for that cute school auditorium setting, a tune from Rabindra Sangeet. The melody chosen was not matching the mood of the situation, as our nuanced composer viewed it, but Hrishida was still particular about Vasant Desai’s rehearsing Vani Jairam for the Rabindra Sangeet tune chosen. Vasant Desai therefore vocally readied Vani for both tunes before urging Hrishida to listen to his original composition first and feel free to reject it –in which case he would Rabindra-record Vani without reserve. Upon hearing the composer’s own Hum ko man kee shaktee denaa tune for the situation, Hrishikesh Mukherjee asked Vasant Desai to just go ahead, saying he no longer wanted to hear the Rabindra Sangeet-based tune the composer had additionally prepared. The man had musical class–that is what prompted Ustad Bismillah Khan to take the trouble to come down from Varanasi to Bombay to play for this composer in Goonj Uthi Shehnai (1959). As the first recording somehow failed to come through, no one was more upset than the ustad. ‘Had you not thoughtfully postponed the recording that day,’ confessed the ustad, ‘I would have left for Varanasi the very next morning. During that first recording day I couldn’t get myself to play correctly, hence my drastic decision to go back. I practised all evening and came ready next morning.’

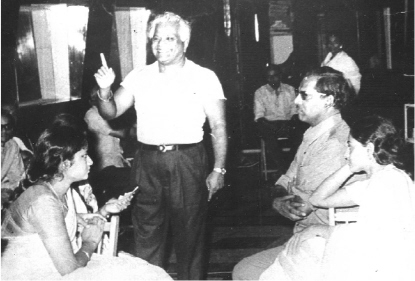

The Neo Guddi of Song –at the 15 December 1970 recording of Bole re

papihara, Vasant Desai readies fresher Vani Jairam (left) –as debutante

heroine Jaya Bhaduri and Hrishikesh Mukherjee watch

Not only Ustad Bismillah Khan but Ustad Amir Khan, too, performed for Vasant Desai with distinction in Vijay Bhatt’s Goonj Uthi Shehnai (1959), the memorable raagmala in the film seeing this composer having that illustrious vocalist exploring the subtleties of Ramkali, Desi, Shuddh Sarang, Multani, Yaman Kalyan, Surdasi Malhar, Bageshri, Chandrakauns and Bhatiyar. What raag variety, what vocal virtuosity, what composing fidelity at a time when our film music was groping for a ‘Hindustani’ stance! After but a brief revival through the 1960s the position was even worse by 1975. In fact, the year 1975 was creatively cataclysmic like none other in the history of Hindustani cinesangeet. A style of music died with the passing of each one going that year–first Madan Mohan on 14 July, then Sachin Dev Burman on 31 October and, finally, Vasant Desai on 22 December. In Vasant Desai, we lost a rough diamond strikingly untouched by the varnish of glossy vacuity. In 2010, more than 34 years after he breathed his sonorous last, we divine, with a pang, that Vasant Desai’s music belonged to the court, not the courtyard –Main saagar kee mast lahar, tuu aasmaan kaa chaand/ Milan ho kaise, milan ho kaise, milan ho ka.i.i.i.se… (1953: Dhuaan–Lata & Chorus). When tuning with Lata (Ram Rajya, 1967), it could be Dar laage garje badariyaa (in Raag Surdasi Malhar). When vibing with Asha (Shaque, 1976), it could be Mehaa baras ne lagaa hai aaj ki raat (in Raag Jayanti Malhar). When equating with the stripling Vani Jairam (Guddi, 1971), it could be Bole re papihara (in Raag Mian Ki Malhar) –in each instance, a composition rendered in the particular singer’s musical idiom.

All musical things to all singing people was Vasant Krishnaji Desai. The man who gifted Vani Jairam to Hindustani cinema was, at heart, a rustic whose music stood rooted in the soil. His grip on folk forms, allied to the depth of his classical knowledge, made him sound at once thematic and authentic. In every single composition of his –ranging from Saiyyan jaaao jaaao (in Raag Des, on Sandhya, in Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje, 1955) to Mere sur aur tere geet (in Raag Bihag, on Ameeta, in Goonj Uthi Shehnai, 1959) –you got the feel of Indian values, Indian tradition. That is why his compositions from the Marathi Amar Bhoopali (1951), moving from Tujhya preetee che (in Raag Yaman Kalyan) to Ghanashyama sundara (in Raag Bhoop), continue to engross us so many years after he created them. Indeed Tujhya preetee che could arrestingly re-emerge (in Lata’s melismatic voice) as Bade bhole ho–going on Screen Sita’ Meena Kumari playing Ardhangini (in 1959). Similarly, Shankerrao Vyas’s Saraswati Rane-rendered 1943 Raag Bhimpalasi classic, Veenaa madhur madhur kachchu bol, could reinvent itself as Lata’s Rain bhayee so jaa re panchchee in Vijay Bhatt’s 1967 Ram Rajya remake. Like in the instance of his being the ‘Guest Music Director’ (under the Prakash Pictures’ Vijay Bhatt banner) in Goonj Uthi Shehnai (1959), Vasant Desai (once V. Shantaram gave him the Rajkamal permission) could compose –for Sohrab Modi and that legendary maker’s Minerva Movietone – something so enrapturing, for Sheesh Mahal (1950), as Jise dhoondhtee phirtee hai meree nazar –as a Geeta Roy–Mohammed Rafi duet.

I still remember how Radio Goa mysteriously persisted in crediting this Geeta-collaborated duet to one Parsee ‘Bapsy’ alongside Rafi! Vasant Desai just let that pass. His contention was that, after all, his Sheesh Mahal compositions deserving true notice were the two Shamshad Begum solos: Dhoop chhaon hai duniyaa and Husn waalon kee galiyon mein jaana nahein. By the same token, in Sheesh Mahal again, Vasant Desai deftly adjusted to the dubious singing-star vocals of Pushpa Hans in a vein of Aadmee woh hai museebat se pareshaan na ho. He believed in making the best of finding himself stuck in the vocal bargain basement. Thus, if the eye-holding Jayshree it had to be, in a not so ear-holding 1950 Dahej strain of Ambuva kee daaree se bolee re koyaliya, Vasant Desai readily attuned to such a marginally ‘singing’ heroine as an inevitable part of the Rajkamal ethos. ‘Hamaara kyaa, hum toh faqeer aadmee hain, kahein bhee chale jaayenge!’ philosophized Vasant Desai as he neared the end (1942–75) of a long distinguished innings in the big-bad crassly commercial film industry of Bombay.

Within a month of saying that, towards the end of December 1975, he was gone. Some way to go –dragged three floors up in his Peddar Road building lift for his head to be smashed to pulp. His mentor, V. Shantaram, summed up the public feeling, in the matter, tellingly when he observed: ‘Today I’m angry with God. To have snatched away such a fine human being in such a ghastly manner. We thus know that to err is Godly.’ He decked the man’s body in flowers that Vasant Desai loved to flaunt on his left wrist. He grimly saw it all through, as the State Composer of Maharashtra was given a state funeral –Nirbal se ladaaii balwaan kee…. A Raag Malkauns-oriented denouement such as this had that 1956 adorer of Toofan Aur Diya’s music, Vani Jairam, rushing down from Madras by the first plane she could get. ‘But the wretched flight was delayed and I couldn’t catch a final glimpse of my Vasantdada,’ she regretted. Vani did not know that her mentor’s face was in no state to be glimpsed.

Vasant Desai tuned with God–Ae maalik tere bandhe hum…. This one came in V. Shantaram’s Do Ankhen Barah Haath at a time (September 1957) when our cinema was viewed to be rejoicing in hybrid O. P. Nayyarized flimflam. Yet it was OP who summed up the piquant position obtaining, in a striking analogy, as he demanded to know how a purist like Vasant Desai (via Lata–Rafi’s Jeevan mein piyaa teraa saath rahe in Raag Gaara on Ameeta-Rajendra Kumar in Goonj Uthi Shehnai) could so strongly Binaca challenge his Geetmala supremacy. And that at a time when Shanker-Jaikishan were accusing O. P. Nayyar of debasing Hindustani cinesangeet.

‘Vasant dada’s house was like a temple,’ wistfully recalled Vani Jairam. ‘Any young lady could fearlessly walk into it even at midnight. How could I possibly forget recording, for this composer’s composer, Bole re papihara, a song still on the nation’s lips as he was so cruelly snatched from our midst on 22 December 1975? But I have to uphold his tradition, whether singing in the South or the North. I shall uphold it in a Kedarian Guddi spirit of Hum ko man kee shaktee denaa.’ Vasant Desai was the first Hindustani composer to invade the South with his hymn of Ghanashyama sundara shridhara arunodayaa jhaalaa from the Marathi Amar Bhoopali (1951). His scores for the Marathi Lokshahir Ramjoshi (1947), Sakharpuda (1949) and Shyamchi Aai (Acharya Atre’s 1953 President’s Gold Medal winner) underlined his integrity as a grass-roots composer.

In the context of his set association with V. Shantaram through Prabhat and Rajkamal, there was this feeling that Vasant Desai’s musical base was predominantly Marathi. It was and it was not. For example, he did derive his (1961) Sampoorna Ramayan Purya Dhanashri-tinted Ruk jaa o banvaasee Ram sweetness from his Marathi base. But he also broadened this base to encompass the vision of Akhand Hindustan in a spirit of Bolo woh hai kis kaa desh, bringing, in the process, a noteworthy Sab koh pyaar kee pyaas cadence to the title tune of that visual stunner unfolding in 1961 as Pyar Ki Pyas –Mahesh Kaul directed and India’s first colour film in CinemaScope. Vasant Desai’s music was steeped in Indian culture, yet its language was universal. That is how his baton could embrace, in its grand sweep, the 1953 Monsoon’s background score, a job he was invited to do (by British producer Forrest Judd) as unusually adept in this specialist sphere. (Monsoon, a British Technicolor drama filmed on location in India, starred Ursula Theiss as Jeannette and George Nader as Burton. It was based on a play by Jean Anouilh and directed by Rodney Amateu.)

Inside Rajkamal itself, if it was C. Ramchandra who so ear-rivetingly created the all-time tunes of V. Shantaram’s Parchhain, Vasant Desai was the one called upon to do that 1952 film’s background score. The man did the job with panache (as Rajkamal Kalamandir’s studio composer). Soon after, in the case of India’s first film in Technicolor, Sohrab Modi’s Jhansi Ki Rani (1953), this remarkably open-minded composer attuned instantly to the idea of introducing certain songs into the film at the last moment. Amar hai Jhansi Ki Rani and Rajguru ne Jhansi chhodee are two Mohammed Rafi numbers you readily recall from that Minerva Movietone blockbuster to which Vasant Desai’s services came to be Rajkamal loaned. Years later, something similar happened with Yaadein, the offbeat 1964 film witnessing Sunil Dutt playing ‘The One and Lonely’. At the eleventh hour, the concept of having only a background score (to vivify the one-man show) was given up for Vasant Desai to come up with Lata’s Dekhaa hai sapnaa koee and Aa gaye Krishna Muraree. Likewise Vasant Desai had no qualms about scoring only the background music of Achanak when that 1973 Gulzar gripper studiedly had not a single song in it.

With Vasant Desai, the theme came first, the tune after. The tunes, vis-à-vis the voluptuously Arcadian Sandhya, had a folksy ring all their own in Do Ankhen Barah Haath in the 1957 shape of Saiyyan jhooton ka badaa sartaaj niklaa, Ho umad ghumad kar aayee re ghataa and Tak tak dhoom dhoom tak tak dhoom dhoom. Yet what rounded off the breakaway V. Shantaram theme was Vasant Desai’s background scoring, encapsulating the heartbeat of India. If Vasant Desai felt saddened at his V. Shantaram–Rajkamal umbilical cord being severed following Toofan Aur Diya (1956), Do Ankhen Barah Haath (1957) and Mausi (1958), he never said so. ‘Anna [C. Ramchandra] is working hard, very hard, on the music of V. Shantaram’s Navrang,’ Vasant Desai let me know. ‘It’s an outstanding Rajkamal score you are going to get from Anna in Navrang, come 1959.’

It was just like Vasant Desai not to divulge that it was he who had originally begun composing the music for Navrang. He was working on the Bharat Vyas–written Aadha hai chandrama duet when, after a lifetime’s association with V. Shantaram, out of the blue, the vibes between the two went seriously wrong. That saw Vasant Desai swiftly get into his car and drive out of Rajkamal Kalamandir, well knowing that, once out of the studio gate, the watchman was instructed to bar the person so leaving from ever entering the premises again. To the end, Vasant Desai told no one what went so catastrophically amiss during that end-1958 Aadha hai chandrama evening–five years after that, when V. Shantaram unexpectedly sent for him again, he promptly presented himself before his preceptor. V. Shantaram, just then, was precariously perched on a ladder, himself writing the credit titles of Geet Gaya Pattharon Ne (1964)–his last inscription on the board up there carrying the punchline: ‘Background Music: Vasant Desai’. Without even turning while atop that ladder, V. Shantaram said: ‘You have to do this!’ To which,‘Yes, Anna,’ was Vasant Desai’s instant response, though the oral music of Geet Gaya Pattharon Ne had been scored by shehnai wizard Ramlal. Thus did the V. Shantaram connection revive for Vasant Desai to stay on at Rajkamal and compose the music for Iye Maratheechiye Nagree (1965) and its 1966 Hindi edition –the 11 songs-studded Ladki Sahyadri Ki. In that title role Sandhya, no great looker even in her 1957 Do Ankhen Barah Haath prime, came through as a good eight years older and the film failed to take off. The customary flavour too was missing from the Vasant Desai–V. Shantaram bonding, so that the composer was not surprised when there was no fresh Rajkamal call to score.

After Vasant Desai had driven out of Rajkamal Kalamandir following Mausi (1958), after he had told me about how well his 1959 successor, in Navrang, was composing for the film, it was on the tip of my tart tongue to ask: ‘Yet what’s C. Ramchandra without Lata?’ But Idemurred, knowing that the film Navrang, at heart, was still a sore point with Rajkamal’s yeoman composer. In fact, by the 1966 stage seeing Vasant Desai returning, not to Rajkamal, but to ‘V. Shantaram Productions’, to score Ladki Sahyadri Ki, it was Asha all the Sandhya way. Kalavati had our Asha sounded remember, under Vasant Desai’s 1958 Do Phool grooming, via Aayee paree rang bharee kis ne pukaara. Compare this with Lata’s Door andheraa huuaa mast saveraa huuaa (in Raag Bhairavi) from the same Do Phool. Lata and Asha, Rafi and Manna Dey, were integral to Vasant Desai’s music. Yet, like some others, he was never their slave, keeping a healthy ear open for new voices. Following Vani’s soliloquizing of Hari bin kaise jiun ree (1971-tuned to go on Jaya Bhaduri playing Guddi), Vasant Desai gave a big break to Dilraj (Ammi Ko Chummee) Kaur in Rani Aur Lalpari (1975). Moving on to present Kumari Faiyaz in a fascinating new shade via Do nainon ke pankh lagaa kar in Aruna Vikas’s Shaque (1976). No job was too small for Vasant Desai. No film was too big, even where it involved painstakingly synthesizing the Cosmos of India that was Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje (1955). Or when it came meticulously to elevating the heavenly instrumental motif of Goonj Uthi Shehnai (1959). Indeed, how memorably Vasant Desai blended the desee with the videsee (on Chand Usmani and Shyama playing Do Behnen, 1959) through Main natkhat ek kalee. Other Lata–Vasant Desai numbers to cherish are Piyaa te kahaan (in Raag Asavari from Toofan Aur Diya, 1956); Na na na barso baadal aaj barse nayan se jal (in Raag Gaud Malhar from Samrat Prithviraj Chauhan, 1959); Saawan ke jhoole padey (in Raag Pahadi from Pyar Ki Pyas, 1961); and San sanan sanan sanan jaa ree o pawan (in Raag Chandrakauns from Sampoorna Ramayan, 1961). For Mahendra Kapoor (as the Metro–Murphy Contest winner), more than one rare Vasant Desai duet it came to be with Lata–Kalpanaa ke ghan barsaate (from Amar Jyoti, 1965) and Chandrama jaa unse keh de (from Bharat Milap, 1965).

As Vasant Desai rose to his composing peak with Vijay Bhatt’s Goonj Uthi Shehnai in 1959 (a year during which he touched his Hindi movie maximum of five films), only such an intrinsically humble achiever could have talked aloud about retiring. In an industry where people are retired unasked, Vasant Desai was all but taken at his word. Still he had no regrets, for he was something more than a film composer. Where other composers lived for the moment, he lived for the morrow. ‘The world of music is a bottomless pit, the deeper you go, the more you realize how hollow is your knowledge,’ he would reminisce. Yet not once was he shallow or shoddy in his approach. You went to his Peddar Road bungalow, not to listen to a foreign tape, but to hear Bhimsen Joshi singing during the Ganpati festival so piously celebrated throughout Maharashtra. So classically committed did our top Hindustani music stalwarts find Vasant Desai to be (in the tawdry world of Bombay cinema) that they readily agreed to perform in the Godly atmosphere prevailing in his home shorn of all symbols of pelf. As someone of Bhimsen Joshi’s vocal stature so performed in this composer’s abode during Ganpati, you were gripped by a terrific sense of ‘atmosphere’. You sensed, in a flash, why Vasant Desai had the essence of music in him–he drew all his inspiration from within.

Few others in our films were as esteemed by our classical musicians as Vasant Desai. Indeed, as I beheld Amir Khan dropping into ‘Sangeetdas’ Brijnarain’s Sur-Singar Samsad office in the Fort area of Mumbai, that ustad would hear of none save Vasant Desai, Naushad Ali and S. N. Tripathi to adorn such a classical institution’s movie awards committee. The Raag Adana notes of the same Amir Khan’s 1955 title song, going as Jhanak jhanak payal baaje, were, I remember, identified as Raag Bhairavi by Svami Agehananda Bharati writing in The Illustrated Weekly of India! Scandalized did Vasant Desai feel upon reading this at a time when the Raag Bhairavi choice, in Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje, actually lay between Lata’s complex Mere ae dil bataa and her straightforward Jo tum todon piyaa. As I wondered if Lata–Hemant Kumar’s Nain so nain naahein milaao (from the same Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje) was in Raag Bageshri, Vasant Desai gently corrected me by underpinning it as Raag Rageshri.

A gentle giant he was, as he worked with total commitment on the dance ensembles of Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje (1955). Yet Vasant Desai could sense that V. Shantaram was worried. The preceding two Rajkamal films had done none too well, so that, on an impulse, Vasant Desai remarked: ‘Shantaramji, I suggest you drop me and take Naushad for Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje. After all, you are staking your all on the film and you need a name that sells.’ But V. Shantaram would have none of it. Vasant Desai was his discovery and he had total faith in the craftsmanship of the man who had scored (for his then fledgling Rajkamal Kalamandir) such ever green movies as Shakuntala (1943), Parbat Pe Apna Dera (1944) and Dr Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani (1946). So did Vijay Bhatt leave the landmark score of Goonj Uthi Shehnai (1959) to Vasant Desai’s steeped-in-classicism care. On the very first day of that super tuneful film’s recording, believe it or not, shehnai wizard Ustad Bismillah Khan failed to take off. Evidently in some trepidation, still, about sullying his name by performing for ‘a mere film composer’, Bismillah Khan had come to the movie’s maiden recording with an air of supercilious contempt. To discover Vasant Desai to be making the calibre of classical demands he had not anticipated from ‘a mere film composer’. Whereupon Vasant Desai sensed the delicacy of the situation in a trice and diplomatically attributed Bismillah Khan’s failure to get going (that crucial morning) to the offputting rain-patter outside. As Bismillah Khan nodded vigorous assent, Vasant Desai shrewdly cancelled the day’s recording, arguing that they could always do it the following morning, once the rain let off. Result–Bismillah Khan came mentally much better prepared and ‘played like the champion he always was’–to quote Vasant Desai. This dedicated composer rarely employed more than 10 musicians. With their aid, he gave to our cinema some of its finest musical moments.

Though Vasant Desai came to films after proving his prowess as a wrestler, he never believed in the ‘freestyle wrestling’ to which our ‘fight composers’ reduced Hindustani cinesangeet in his final years. To him the job of composition was a mission. Awards and rewards meant little. The nearest he came to winning everyday notice was when he got to finish 3rd in the 1959 Binaca Geetmala –179 points for Maine peena seekh liyaa and 109 notches for Keh do koee na kare yahaan pyaar (both by Rafi, on Rajendra Kumar, in Goonj Uthi Shehnai). A year before that (1958), Vasant Desai had collected 135 points for Lata–Talat Mahmood’s Tim tim tim taaron ke deep jale (from Mausi). Indeed the same Lata–Talat’s cute 1959 School Master duet, O dildaar bolo ek baar (going on Garden City beauty Saroja Devi and Raja Gosavi), had caught the instant fancy of viewers and listeners. Vasant Desai had, a year earlier, staged his maiden entry into Binaca Geetmala (at No. 14) with Lata–Talat’s 1958 Mausi duet:Tim tim tim taaron ke deep jale. As this one climbed to No. 13 in the week following, his then school-going nephew Vikas Desai –who grew up to make Shaque in 1976 –taunted Vasant Desai to say: ‘Mama, your Tim tim tim is going to be out of Binaca in two weeks, wait and watch!’ Wryly smiling, Mama Vasant Desai responded: ‘Why two weeks, my song could go out next week. Understand, Vikas, that I don’t compose for Binaca Geetmala or for record sales. My songs are composed for my film –for that character, for that situation, for that emotion. The song finishing Binaca Top today would remain there, say, for 10 weeks–only to be forgotten in three-four months after that. My song might never enter Binaca but if my creativity is true creativity, which I think it is, my songs would get to be remembered 25 years after I am gone.’ Vikas Desai points to how it is nearly 35 years since his Mama is gone, how his compositions like Ae maalik tere bandhe hum are forever.

The time his 1959 School Master duet, Lata–Talat’s O dildaar bolo ek baar, made it fairly prominently to the Binaca Geetmala, Vasant Desai slyly pointed out to me that this happening proved he was not without the popular touch! He said that with a grin, as a composer who had the gift of looking cheerful in the most daunting setting. The lure of lucre, something always driving our cinema, had left Vasant Desai untouched. As the true faqeer of cinesangeet, Vasant Desai brought to motion picture art and craft a musical vision extending way beyond the meretricious silver screen. Divine was his touch even as Hindustani cinema wallowed in shimmery mediocrity. Amidst such a misplaced accent on ephemera, who but Vasant Desai could have added lustre to Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s 1968 Aashirwad with a classical creation of rare substance? Lata, I felt, came to be heard at her limpid best, here, on Sumita Sanyal (vis-à-vis Ashok Kumar) when Vasant Desai told me that, in a particular jhatka (turn), he felt sad that he had not got, from the melody queen, the exact shade of vocal expression he keenly wanted. To this day, I am at a loss to comprehend as to where precisely Lata falls short in such a perfect Raag Gujjari Todi Aashirwad rendition as

Ek thhaa bachpan ek thhaa bachpan

Chhota-sa nanha-sa bachpan

Bachpan ke ek baboojee thhe

Achche sachche baboojee thhe

Donon ka sundar thha bandhan

Ek thha bachpan…