The tandem was a specialist field in which there was no way to overtake Talat. And Lata knew it. In fact, it was Talat whose hypnotic vocals first exposed this sole (tandem) chink in Lata’s otherwise formidable singing armour. A tandem recording gave Lata the creeps. Not that Lata, on the tandem podium, feared Kishore Kumar, Hemant Kumar, Mohammed Rafi, Manna Dey and Mukesh less, but she feared Talat more! Why only Lata, Talat, at his ghazal pinnacle, gave each one of our top male singers something of a complex.

Our unquestioned No. 1 male performer, until he chose to turn a singing-star, Talat Mahmood remains a part of our ‘ghazalandscape’, as his is the voice in which the nation once made love –Mohabbat kee dhun beqaraaron se poochcho beqaraaron se poochcho. This Ghulam Mohammed-composed beauty as well as the melancholic Zindagi dene waale sun figured in A. R. Kardar’s ill-starred Dil-e-Nadan (releasing in June 1953) after the film had been originally titled Naashad (to spite a Naushad having no use for either Talat Mahmood or A. R. Kardar any longer)! As rendered by Talat Mahmood (with Sudha Malhotra and Jagjit Kaur in shagird tow), Mohabbat kee dhun is a number not without a dash of irony. Dil-e-Nadan –with Talat Mahmood as its debutant hero opposite fresher Peace Kamal (Kanwal) and tempter Shyama – bombed with a thud that left the Ghazal King battling to retrieve his crown. After that, each one of his 8 films as a hero (released through the 1950s) merely ensured that the ‘crooner’s crooner’ progressively shed his unique niche as the velvety voice-choice of millions. There was a time (1950–55) when, where Talat led, even Lata Mangeshkar followed –in the sense that, for all her vocal omnipresence on the film scene, Lata’s name could not be taken in quite the same sentimental breath as Talat’s.

Mohabbat kee dhun beqaraaron so poochcho:

Talat Mahmood in Dil-e-Nadan (1953)

Hence, where even Lata had to tread carefully, for Asha Bhosle to have been dismissive of a singing icon like Talat Mahmood (in the early-2009 K for Kishore Sony TV show) came as something of a culture-vulture shock. Asha, while speaking of the 1950 Khemchand Prakashtuned Jaan Pahechan duet, Armaan bhare dil kee lagan tere liye hai (picturized on Nargis-Raj Kapoor), was narrating how this yugalgaan’s female segment had gone to her senior playback bogey, Geeta Roy, adding: ‘Unke saath koee ek male singer Mehmood-Mehmood kar ke thhaa…’ (‘With her was a male singer whose name went as such-and-such a Mehmood…’) This was virtually like Asha Bhosle’s asking: ‘Who is Talat Mahmood?’ This was not only shocking but in utter bad taste. If anything, Asha Bhosle should have been grateful that such a performing great as Talat Mahmood deigned to sing as many as 15 duets with her during her 1951–59 struggle phase itself. Maybe Asha’s duets with Kishore Kumar number 589 compared to her total of 55 with Talat–but Asha, please do pause to consider how much each one of those 55 duets meant to you in your formative years as a playback singer. How could you forget, Asha, that this was the span (1950–55) that witnessed you as suffering from a Lata complex all along the line.

Prominent among such Asha come-through duets with Talat, in such a forbidding setting, are S. D. Burman’s Chaahe kitnaa mujhe tum bulaao jee (on Madhubala-Dev Anand in Armaan, 1953); Ali Akbar Khan’s Kisee ne nazar se nazar jab milaa dee (on Kalpana Kartik-Dev Anand in Humsafar, 1953); Surya Kumar Pal’s Mere jeevan mein aaya hai kaun (on Nimmi-Rehman in Pyaase Nain, 1954); and Madan Mohan’s Kehtaa hai dil tum ho mere liye (on Meena Kumari-Shammi Kapoor in Mem Sahib, 1956). In RK’s Boot Polish (releasing in January 1954), was it not on song-writer Shailendra himself that Jaikishan’s Chalee kaunse desh gujariyaa tuu saj-dhaj ke came to be picturized in Talat’s reshmee voice even as you, Asha, picked up the Jaaoon piyaa ke desh rasiyaa main sajdhaj ke refrain on a Naaz already showing her performing paces? How perennial, Asha, is your 1956 Chitragupta-tuned Insaaf duet with Talat as written by Asad Bhopali to go on Nalini Jaywant-Ajit as: Do dil dhadak rahein hain aur aawaaz ek hai. Next, Asha, picture how –following the 1957 waves you made via O. P. Nayyar’s Naya Daur –your Lala Rukh Khayyam-toned, Kaifi Azmi-penned duet, Pyaas kuchchh aur bhee bhadkaa dee jhalak dikhlaa ke (on Shyama-Talat), came as a timely 1958 Radio Ceylon career booster? Recall how those days, Asha, when a ‘next-inline’ singer for Lata was being considered, the vote, near automatically, went to Geeta Roy. Asha Bhosle just did not make the cut. How Asha struggled to make the higher grade those days!

Chaahe kitnaaa mujhe tum bulaao jee … Asha was still a struggler when

Ghazal King Talat Mahmood accommodated her in 55 duets, helping give

her career a fillip at a mid-’50s point when it was Lata all the way

For the Ghazal King Talat Mahmood to have agreed to sing with you then, Asha, was an act of Lucknowi grace. Reflect upon how in those times (1951–55), Asha, whenever there was a mehfil where all our top male voices sang, Talat Mahmood always was star-billed as the last artiste to perform during the evening? How effortlessly Talat would outstrip them all with an aromatic array of ghazals? Whereupon Kishore Kumar once walked up to Talat to say: ‘I think I had better give up singing! How on earth do I match your Urdu diction and inflexion, your soz?’ Talat’s vintage virtuosity just no one rivalled. Seeing and listening therefore to you, Asha –groping for Talat’s name in the open –was something not only most ungracious but unpardonable. Something that made every single seasoned viewer watching you, on Sony TV, feel shattered.

As Asha well knows, certain themes then presupposed the voice of Talat and Talat alone. A sensitive Bimal Roy-directed theme such as Devdas, for instance. Before undertaking Devdas under his own banner, Bimal Roy had treated Saratchandra themes with rare sensitivity in Ashok Kumar’s Parineeta (1953) and Hiten Choudhury’s Biraj Bahu (1954)– from among the two, the 1953 film fetching Meena Kumari the Filmfare Best Actress prize, while the 1954 movie won for Kamini Kaushal a similar honour. All through the casting stage of Devdas, on one side there was a debate about who should be playing Parbati and who should be essaying the role of Chandramukhi. On the other side raged a controversy as to who should be composing the 1955 Devdas music against the backdrop of K. L. Saigal’s near indestructible visage in that unforgettable 1935 role. Photographing that Promathesh Barua-directed New Theatres’ Devdas (in his first independent assignment as a cameraman) was –hold your breath! –Bimal Roy, whose life’s lens-dream it thus became to remake the 1935 K. L. Saigal classic. A classic having sarod ace Timir Baran surpassingly tuning the songs written by Kidar Sharma, songs set to ‘evergreen’ Kundan Lal Saigal in a rich vein of Dukh ke ab din beetat naahein; Piyaa bin aavat nahein chain; and Baalam aaye baso more man mein. Finding a music maker to replicate the unique Devdas aura created by Timir Baran on K. L. Saigal–even given the silken vocals of Talat Mahmood –was, therefore, going to be far from easy.

Salil Chowdhury had scored Biraj Bahu with distinction for Bimal Roy, with his two Hemant Kumar bhajans on one N51010 78-rpm record –going on Abhi Bhattacharya as Jhoom jhoom Manmohan re and Mere man bhoola bhoola –becoming a collector’s item. But Salil Chowdhury was not a name that could sell Devdas. So, on Dilip Kumar’s prompting, Naushad was approached–by then, sadly, a non-Talat tuner. Bimal Roy was hardly enthused by Naushad’s suggestion that K. L. Saigal’s enthralling vignettes (from New Theatres’ 1935 Devdas) should be left intact in the film’s 1955 remake, for that ‘singing-star of singing-stars’, himself, to emerge as Dilip Kumar’s playback in the remake! It was Naushad’s subtle way of saying ‘no’ to Bimal Roy, keeping in view the fact that the voice of Talat for Devdas was a must in the Bengali camp. Moreover, Naushad then charged a lakh of rupees for a film, which was way beyond Bimal Roy’s budget. So in came Sachin Dev Burman as the Rs 20,000 man though, mind you, even Dada was distinctly nervous about re-creating the K. L. Saigal part of the Devdas legend. When told that it had to be the makhmal-soft voice of Talat on Dilip Kumar in the title role, Dada Burman felt further unnerved as, for all his musical erudition, he never really tuned with our Bengali-oriented singing idol, even given the man’s literary artsand graces. Dada Burman finally settled for just acouple of solos unfolding, in telling snatches, on Devdas Dilip Kumar.

What feeling, what meaning Talat brought to his Raag Des interpretation of Mitwaa mitwaa laagee re yeh kaisee anbuj aag mitwaa nahein aaye. No less impactive, on the Dilipian Devdas, was SD’s Kis ko khabar thhee kis ko yakeen thhaa as soliloquized on our thespian’s visage by Talat. Talat’s ‘ghazalizing’ left one wondering how, in the same Devdas, Lata Mangeshkar was going to match him while vivifying those prize mujhraas to go on Vyjayanthimala playing Chandramukhi. SD’s doubters were proved wrong. Dada Burman teamed with Sahir Ludhianvi to arresting effect as he brought in Ustad Ali Akbar Khan on the sarod and Abdul Karim on the tabla. Vyjayanthimala as Chandramukhi was viewed to be sheer quicksilver in her dance movements, attracting amazing attention via her histrionics, too, opposite a Dilip Kumar playing Devdas with subdued empathy. A subdued empathy underscored by Talat’s serene vocals. Vyjayanthimala simply excelled herself as she enacted Ab aage teree marzee; O jaane waale ruk jaa koee dam; and Jise tuu kabool kar le. These SD–Sahir numbers by Lata were tuned feelingly enough for viewers to be able to audio-visualize Chandramukhi’s percipient progression from a mere nautch-girl to a caring Devdas saviour. For all that, Suchitra Sen as Parbati had reserved her best for the Devdas climax. All the high histrionics latent in the volcanic Suchitra erupted in one parting shot, the Bengal diva creating this electric effect without a single SD song going directly on her.

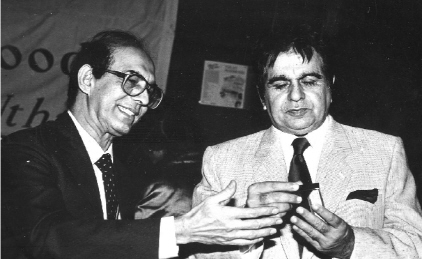

Sapnon kee suhanee duniyaa ko … Talat knew no Shikast

as Dilip Kumar’s voice

After all this, Bimal Roy’s Devdas was but a critical success. Even Talat Mahmood –granted his vocal charisma –could not alter the fact that K. L. Saigal had pre-written this remake’s box-office fate. But Dada Burman, in his complex composing task here, teamed so surpassingly with Sahir via Talat and Lata that to this day I wonder as to how and why SD always rated Shailendra as the finest of the poets writing for him. Also, Dada Burman was not, for some obscure reason, ever for Talat. Strange when you recall that it was Talat’s (not Lata’s) poignant Raag Jaunpuri rendition of the Jaayein toh jaayein kahaan tandem –on Dev Anand playing Taxi Driver –that had fetched Dada Burman his career-furthering 1954 Filmfare Best Music award (in the days when this statuette was still for one song, not for the film’s full oral score). Compulsive listening as Jaayein toh jaayein made, it is Talat’s first ghazal for SD, the Rajendra Krishna-written Yeh aansoo khushee ke aansoo hain on Karan Dewan in Ek Nazar (1951), that remains this mesmerizer’s best for that composer. Sadly, Ek Nazar tanked. That set Dada against Talat. Yet how could even such a classy composer, in this industry of commerce, totally ignore the one who rated as numero uno by aristocratic consensus? That explains Dada Burman’s having to commission Talat for those two cute duets with Lata: Dar laage duniyaa se balmaa ho (on Premnath-Nimmi in Buzdil, 1951) and Aa jaa aa jaa teraa intezaar hai (on Dev Anand-Nimmi in Sazaa, 1951).

As Dev Anand winsomely paired with Madhubala in the SD-tuned Armaan (August 1953), it was Talat’s super-romantic voice that set off that lady’s Venus beauty in mellow tones of Bharam teree wafaaon ka mitaa dete toh kyaa hotaa and Bol na bol ae jaane wale sun toh le deewaanon kee/Ab nahein dekhee jaatee hum se yeh haalat armaanon kee, as written by Sahir. Even down South, in AVM’s Bahar (1951), Dada Burman had been impelled to summon Talat for Ae zindagee ke raahee himmat na haar jaana, a spot hit unfolding as a ‘situational backgrounder’. In Babla (end-1953), the film’s artistic makers told Dada Burman pointblank that the thematic Jag mein aaye koee koee jaaye re meant a Sahir solo to be attuned to the soft Bengali-hued vocals of Talat. Alongside, in Amiya Chakraborty’s Shahenshah (1953), Talat’s sustained pull saw him putting over, ambiently for SD, the Arab-atmospheric backdrop solo: Naazon ke pale kaanton pe chale. As for S. D. Burman’s Angarey (1954), how do you –as penned by Sahir –pick and choose between that Talat–Lata heart-stealer (on Nasir Khan-Nargis) going as Tere saath chal rahein hain yeh zameen yeh chaand taare –aduet rated among Dada Burman’s smoothest –and Talat’s super solo: Doob gaye doob gaye aakaash mein taare, jaa ke na tum aaye (on Nasir Khan)? Why then was Dada Burman so grudging about plumping for our crooner without peer when it came to a voice immortalizing Devdas? To think that he just banished Talat from his music room after Devdas –through 12 films over four years.

How possibly –after those four years–could we forget Talat’s Jalte hain jis ke liye, so memorably Majrooh written to go on Sunil Dutt in Bimal Roy’s Sujata (1959)? Outraged felt the Ghazal King as Dada Burman–unusually for him–cautioned before the Jalte hain recording: ‘Don’t spoilmy song, Talat!’ That galvanized Talat into giving Jalte hain jis ke liye (in Raag Sindhura) all he had. Talat was to tell me, later, that only Dada’s age had prompted him to pocket such an SD affront to his singing dignity. Indeed this number saw thoroughbred Talat back in high vocal saddle. Still Dada Burman never bought my argument that Talat remained without match in his métier, for SD honestly felt that Rafi would have done even better vocal justice to Jalte hain. Well, the fact is SD was rarely proved wrong in his vocal judgement. Remember how he saw Kishore Kumar as the coming voice a full 20 years before most other composers? If Jalte hain signalled a welcome comeback for Talat by 1959 (after a highly dismaying loss of stardom), this performer –as one still holding us in a thrall –faced the litmus test when, crucially in his career, performing for Bharat Bhooshan in Vinod Kumar’s Jahanara (1964). That writer-director was stridently insistent upon the theme’s needing the more vibrant vocals of Rafi, all the way, but Madan Mohan, typically, would not budge from his stand that his mind was made up on musically shaping Jahanara into a long overdue comeback for Talat. How Madan stuck to his guns as he restored that velvet feel to Talat’s voice in such Jahanara heart-tuggers (on Bharat Bhooshan) as Teree aankh ke aansoo pee jaao; Main teree nazar ka suroor hoon; Phir wohi shaam wahi gham wahi tanhaaii hai, while side by side proving that our crooner retained the lighter touch, as he dueted with Lata (on Bharat Bhooshan-Mala Sinha) as Ae sanam… ae sanam aaj yeh qasam khaayein. Rafi did find a place in Jahanara through Kisikee yaad mein and Baad muddat ke (duet with Suman Kalyanpur). When Jahanara as a film just folded up, Vinod Kumar blamed it all upon Madan’s obduracy vis-à-vis Talat, but the composer stood his ground, saying the writer-director had messed up the historical narration. Jahanara, if a box-office ‘lukewarmer’, certainly gave Talat’s sagging career a timely shot in the arm–still, astonishingly, there were no real takers for this ultra-soft voice. So much so that the once all-powerful Naushad had been ‘persuaded’ by Manoj Kumar to replace, on his countenance, the voice of Mahendra Kapoor by discarding the vocals of Talat Mahmood in the 1968 Aadmi duet: Kaisee haseen aaj bahaaron kee raat hai (N74634). That such a substitution should have taken place after the Talat–Rafi original had been issued as an HMV record (N74633) hardly redounded to Naushad’s credit. What would Naushad have done, for example, if Raaj Kumar–as first announced –had remained Dilip Kumar’s counterpoint in Aadmi? Raaj being Raaj, where it came to taking on Dilip Kumar, would have been dogmatic, would he not, about Rafi’s voice going on him and him alone?

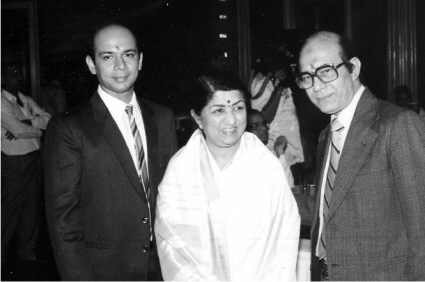

Tere saath chal rahe hain … Lata-Talat dueting was something special, as

the two had a matching aura. At left is son Khalid Mahmood

What is sad is that this ego-shattering blow should have been dealt to such a majestic voice whose reach extended beyond films from the word go. In the sense that Talat Mahmood is like none other in the nonfilm repertoire at his command on demand–a range of nearly 200 ghazals and geets that make his voice unique in its mystique. I could but cursorily touch, here, upon this body of Talat’s work by recalling such captive ghazals of his as Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s Donon jahaan teree mohabbat mein haar ke/Woh jaa rahaa hai koee shab-e-gham guzaar ke; Daagh’s Dil hee toh hai na aaye kyon/Dam hee toh hai na jaaye kyon; Jigar Muradabadi’s Sabhee andaaz-e-husn pyaare hain/Hum magar saadgee ke maare hain; I. A. Meenai’s Raatein guzaar dee hain taaron kee roshnee mein/Afsaane sun chukaa hoon apne hee khamoshee mein; Shamim Jaipuri’s Galey lagaa ke jo sunte thhe dil kee aahon ko/Taras rahaa hoon unheein kee haseen nigaahon ko. No less enchanting, to this day, sound Talat’s array of geets going as Meraa pyaar mujhe lautaa do (Sajjan’s wording so sensitively tuned by V. Bulsara); Madhukar Rajasthani’s Kyaa itnaa bhee adhikaar nahein dhoondh sakoon nazron mein teree apnaa khoyaa pyaar/Dekh sakoon dekh sakoon jee bhar ke tujh ko; Khaavar Zamaan’s Ro ro beetaa jeevan saaraa jeevan saaraa; Faiyyaz Hashmi’s Tasveer teree dil meraa bahlaa naa sakegee/Yeh teree tarah mujhse toh sharma naa sakegee; Raj Merthi’s Ae andaleeb-e-zaar jaane ko hai bahaar. It is this treasure trove in his oeuvre that gave Talat a mehfil edge over each one of our top cine singers. That this his true quality music–needing no visuals to stay embedded in our mindset–is all but lost in the meretricious media medley of today is the tragedy of being Talat Mahmood.

Initial Kishore Kumar spurner Salil Chowdhury certainly shared the feeling that Talat had been shunted out of the singing arena ahead of his time. Aslate as 1961, how tellingly did Salil bring him back (on Sunil Dutt in AVM’s Chhaya) via Aansoo samajh ke kyun mujhe aankh se tum ne giraa diyaa; Aankhon mein mastee sharaab kee kaalee zulfon mein raatein shabab kee; and Itnaa na mujh se tuu pyaar badha kee main ek baadal awaara. Three thinking Salil compositions seeing Rajendra Krishna pulling out something extra from his versatile pen. Never can I forget the June of 1993, when on a visit to Salil’s ambient Calcutta home, I dragged him to the piano by urging him to demonstrate how Talat–Lata’s Chhaya charmer, going on Sunil Dutt-Asha Parekh as Itnaa na mujh se tuu pyaar badha, is not a Western copy. Even as Salil descended on the piano, not for a moment did he deny that Itnaa na mujh se is in Mozart’s G Minor Symphony. But then Salil proceeded to underscore how exactly he got Talat-Lata to transform the original beat. Even as he played Itnaa na on the piano, Salil observed: ‘Doesn’t it sound exactly like Bhairavi? If it’s copying, it’s creative copying. Even Shakespeare plagiarized!’ As the self-styled Pele of Music, Salil had a parting kick all his own. As he kicked off in Bombay with Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin (1953), the word was out that the neo-genius from Bengal had arrived. With Talat, Salil vibed from the word go, as the two shared literary pursuits ranging beyond music. Thus Salil was full of musical ideas as that grassroots film maker Dulal Guha approached him to score, in association with his pet poet Shailendra, the Mala Sinha–Talat Mahmood starrer, Ek Gaaon Ki Kahani (set for a 1957 new year release). What happens when composer and singer are on the same creative wave length is manifest here, as Salil has Talat(as the film’s hero) engrossingly enacting Jhoome re neelaa ambar jhoome dhartee ko choome re and Raat ne kyaa kyaa khwab dikhaye, not to speak of the movie’s Lata–Talat duet going, ever so cutely, on Mala Sinha-Talat as O haay koee dekh legaa. Incidentally, how possibly could welet the Talat–Salil–Latacombo go without making melismatic mention of the threesome’s 1956 Awaaz duet unveiling on Zul Velani-Nalini Jaywant as Dil deewaana dil mastaana maane na? Duets have come and duets have gone but this Talat–Lata two-in-one has stayed ingrained in the imagination.

‘They talk of the vibrato in Talat’s voice,’ reminisced Salil. ‘Only the truly inventive composer could turn that vibrato into his strength, by seeing to it that the vibrato didn’t become a tremolo in the recording room. I ensured that as late as in Chhaya [1961] and Prempatra [1962].’ How one hunted for Salil Chowdhury’s Talat–Lata gems from Bimal Roy’s Prempatra! Gems adorning the personae of Shashi Kapoor and Sadhana as Yeh mere andhereujaale na hotey agar tum na aate meree zindagee mein (as written by Rajendra Krishna) and Saawan kee raaton mein aesaa bhee hotaa hai/Raahee koee bhoola huuaa toofanon mein khoyaa huuaa/ Raah pe aa jaataa hai (penned by Gulzar). Do note how one has to go all the way, with the poetry, when it comes to getting a feel of Talat crooning, something which remains the distinguishing trait of this aristocratic performer’s artistry. Any wonder then that Talat was the first to fade as Hindustani cinema began to lose the mood for the nazaakat going with his poetic voice?

Talk of nazaakat and the musician who instantly comes to mind is Khayyam, a veteran of 55 films and a composer of abiding class and calibre who, in his approach, is the very antithesis of Salil Chowdhury. Remember Khayyam’s 1953 movie bow with Zia Sarhady’s Footpath, the show in which this mauseeqaar was viewed to ‘all-time’ Talat’s Shaam-e-gham kee qasam on Dilip Kumar? Having so obliged one who was a freshercomposer then, Talat naturally assumed that it would be none but him singing, for Khayyam, the prestigious early-1969 Ghalib – Portrait of a Genius album (LP ECSD 2404). All the more so as, apart from performing for him in films, Talat had been spot-picked by Khayyam to render (on 78-rpm) three prize Ghalib creations.

Talat just could not believe it when I told him that, by way of a centenary offering, it was going to be Mohammed Rafi vocalizing Ghalib for Khayyam. ‘How possibly could a Punjabi sing Ghalib?’ Talat indignantly sought to know. ‘Only a UPian like Talat could vocally give expression to the finer points of Ghalib. There is to it a certain enunciation, a certain inflexion, a certain intonation that is the perceptive preserve of a UPian ghazal exponent of my Lucknowi standing.’ If his choice of English words was impeccable, Talat’s intellectual insouciance, then, had to be experienced to be absorbed. How memorably did Talat (under Ghulam Mohammad’s baton) thematize Mirza Ghalib (1954) for Bharat Bhooshan, opposite a Suraiya so poignantly playing Chaudhvin Begum–Dil-e-naadaan tujhe huuaa kyaa hai. As a solo performer too, on Mirza Ghalib so pat-portrayed by Bharat Bhooshan, Talat came through in a compelling vein of Phir mujhe deeda-i-tar yaad aaya and Ishq mujh ko nahein wehshat hee sahee. ‘But Talat,’ I interjected,‘your voice was always precious to Khayyam. Was it on Dilip Kumar’s urging that you put over Shaam-e-gham kee qasam for 1953 debutant Khayyam in Footpath?’ To which Talat shot back: ‘No call for Yusuf to say so, I was already Dilip Kumar’s established voice by then! In fact Khayyam, in Footpath, was a beginner to whom I could have said “No”, such then was my stature. So Khayyam had to be grateful to me, not the other way around. Never thought Khayyam would sideline me in my own bailiwick–Ghalib.’

Rafi went on to sing the seven Khayyam-tuned ghazals, on that Ghalib album, with distinction, while Talat steadily lost ground in showbiz. Then, in a remarkable turn of events by 1974, Rafi (when no longer reigning supreme) astonishingly stopped singing for Khayyam. Nothing Khayyam said during a telephonic ‘shoutout’ could shake Rafi in his resolve. How angry Khayyam then was with Rafi: ‘You know, Rafi’s Jaane kyaa dhoondhtee rahtee hain yeh aankhen mujh mein went into 21 takes for Ramesh Saigal’s Shola Aur Shabnam [1961]. Only I know how the cut-and-paste job was undertaken to make it sound the classic it does today.’ Kaifi Azmi’s Jaane kyaa was set in Khayyam’s patent Pahadi. It was in the same Pahadi idiom that Rafi and Khayyam reunited, as our master performer joined Lata (on Raaj Kumar and Moushumi Chatterjee in Chambal Ki Kasam, releasing January 1980), enrapturing us with Simtee huuee yeh ghadiyaan phir se na bikhar jaayein. Before that, we had from Khayyam Rafi’s super Kamal Amrohi-written Kahein ek maasoom naazuk-see ladkee (in the long-delayed Shankar Husain, finally releasing in February 1977).

Rafi had the humility to make up with Khayyam via the very telephone instrument that he had employed to disengage from him. By contrast, Talat, when the crunch came, discovered that he was not so fortuitously placed: ‘It always was the composer who had rung and requested me to come and perform at a recording. I was at a total loss to know about how to connect, when such composers’ calls suddenly stopped coming,’ ruefully pointed out Talat. ‘Come to think of it, my own Lucknowi aristocratic style of waiting for the composer to make the Pahele aap-move proved my playback drawback. The concert tours on which I went away, feeling frustrated after shedding stardom, further worked against me. Once stardom deserted me, I should have just stayed back and displayed the gumption to ring up composers. My false sense of pride proved my undoing.’

This was the first touch of humility I came to spot on the part of a Talat still envisioning himself to be in his prime. Talat further noted that Lata too was not overkeen to sing with him, by the 1964–65 stage– she, like certain composers, felt that Talat should have been working harder upon trying to eliminate the vibrato in his voice. To think that the same vibrato’s creeping into her voice is what –as Naushad saw it – began to make Lata sound (by her standards) a near listening disaster, as her supple vocals lost the gift of remaining thehraao (staying steady). ‘If you corrected her in one detail, she lost vocal poise at another point – this no longer was the flawless Lata I knew!’ concluded Naushad.

The maiden occasion on which I got a sensation of its being the original Lata on the phone, it had been no dulcet-different from the first time Talat gave me a tinkle–for me to get a feel of the sheer velvet in his voice: ‘You won’t guess in a thousand years who this is ringing you–it is one Talat Mahmood calling to thank you for the Filmfare article [of 29 March 1967] on me that has had the magic effect of setting my phone ringing, exactly the way it used to do in my peak ghazal-singing years! Thank you very much, Raju Saab. Thank you all the more for identifying my [1953] Shanker-Jaikishan linkage through Sapnon kee suhaanee duniyaa ko aankhon mein basaa na mushkil hai on Dilip Kumar in Shikast. Rather than through that choice cliché, Ae mere dil kahein aur chal, in the same Dilip Kumar’s Daag!’ Yet Daag (1952) and Talat Mahmood’s Ae mere dil kahein aur chal illumine another Lata sore point vis-à-vis our ghazal superstar. Lata’s Ae mere dil kahein aur chal edition on Nimmi, if well rendered, somehow suffers in comparison with the Talat original on Dilip Kumar. Likewise, Lata made compulsive hearing as she rendered debutant Jaidev’s Subah ka intezaar kaun kare on Sheila Ramani in Chetan Anand’s Joru Ka Bhai (1955). Yet the moment Talat came through with Teree zulfon se pyaar kaun kare (on, believe it or not, Goldie Vijay Anand making his acting bow in the same Joru Ka Bhai) Lata somehow sounded as taking a tandem beating. The same Lata–Talat tandem phenomenon is to be experienced in Madan Mohan’s Meraa qaraar lejaa mujhe beqaraar kar jaa (on Nargis-Raj Kapoor in Ashiana, 1952); Husnlal-Bhagatram’s Ae meree zindagee tujhe dhoondhoon kahaan (on Meena Kumari-Pradeep Kumar in Adl-e-Jehangir, 1955); and Ravi’s Sub kuchch lootaa ke hosh mein aaye toh kyaa kiyaa (on Madhubala-Ashok Kumar in Ek Saal, 1959). As for Jaayein toh jaayein kahaan on Dev Anand as Taxi Driver (1954), this Sahir-written ghazal-tandem saw Talat just outclassing Lata on Kalpana Kartik. Over then to Roop Ki Rani Choron Ka Raaja, the 1961 Waheeda Rehman–Dev Anand starrer embodying the Shankercomposed Lata–Talat tandem: Tum toh dil ke taar chhed kar ho gaye bekhabar. Lata-Waheeda, here, should have had the drop on Talat-Dev but Lata didn’t –even when (by 1961) she was beyond doubt our No. 1 singer while Talat had lost his vocal ascendancy.

The tandem was thus a specialist field in which there was no way to overtake Talat. And Lata knew it. In fact, it was Talat whose hypnotic vocals first exposed this sole (tandem) chink in Lata’s otherwise formidable singing armour. A tandem recording gave Lata the creeps. Not that Lata, on the tandem podium, feared Kishore Kumar, Hemant Kumar, Mohammed Rafi, Manna Dey and Mukesh less but she feared Talat more! Why only Lata, Talat, at his ghazal pinnacle, gave each one of our top male singers something of a complex. His son Khalid Mahmood has digitally ‘remastered’ practically Talat’s entire career-range (720 songs out of 747) on a single CD, which undoubtedly is a collector’s passport to the wonderland of a dream singer. ‘If our sweetest’ Talat ‘songs are those that tell of saddest thought’, the Percy Shelley stream of thought, how tenderly transliterated it is by Shailendra via Shanker on Dev Anand in Patita (1953) as:

Hain sab se madhur woh geet jinhein

Hum dard ke sur mein gaate hain

Hum dard ke sur mein gaate hain

Jab hadd se guzar jaatee hai khushee

Aansoo bhee chhalakte aate hain

Aansoo bhee chhalakte aate hain

Hain sabse madhur woh geet…