Pancham buffs might hate to hear this, but the sad truth is that their pet composer answering to the name of R. D. Burman never really overtook Laxmikant-Pyarelal in the box-office stakes….All along Pancham rested on his trendsetting oars, happy only among his own select group of hangers-on…. He waited for things to happen, never ever venturing to make things happen…

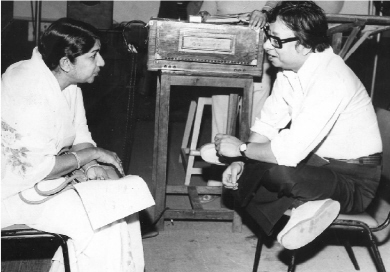

Mid-October 1984. The terminally sick sister of the ‘Old Lady of Bori Bunder’, The Illustrated Weekly of India, as The Times Group’s magazine flagship, faced the gravest crisis in its 104 years of publication. It had indefinitely closed for neo-Editor Pritish Nandy to organize a total revamp. Pritish wondered if I, as a long-time confidant of our track-blazer composer, could do a life-and-times interview that would have Pancham speaking on the theme of how S. D. Burman shaped R. D. Burman. Pancham, as was typical of him, asked me to come over straightaway to Famous Cine Labs at Mahalaxmi where – during gaps between the recording (actually dubbing) of a song for Rahul Rawail’s 1985 Sunny Deol starrer Arjun– he would be free to talk. On my reaching the recording studio (on Tuesday, 16 October 1984) Pancham told me that Lata Mangeshkar had already arrived (by 9.00 a.m.) for the dubbing – if I could just wait while he exchanged ‘notes’ with her. Just like Pancham to be tactless enough to call me on a Lata-recording set! At least Lata and I were, again, on talking terms by then – if we encountered each other in public – after a decade-long interregnum in our cordial interaction. During this 1974–83 decade, the Melody Queen had ceased tuning with me as I became stridently critical of the singing monopoly established by the Corsican Sisters (Lata and Asha), as I proceeded to detail how the two were sedulously blocking the advent of a fresh stream of voices.

Following this prolonged chill in our relationship, end-December 1986 saw me launching the long-running Rahein Na Rahein Hum music column in Nikhil Wagle–Meena Karnik’s popular Mumbai-based Marathi fortnightly: Chanderi. By prior editorial agreement with Meena, I was here to touch, primarily, upon the positive contribution of the Mangeshkars – in line with the expectations of a Lata-adulating Marathi readership. This was the development that was to witness a genuine thaw in my stand-off with Lata. But right now – over two years before that Marathi column’s advent – since Lata and I were no longer personae non gratae, I thought it would be only good manners to go in and personally greet our greatest-ever chanteuse. As I entered the recording studio to say a hearty ‘namaste’, Lata just froze. It was clear she had least expected to see me at the recording. Predictably, she sent for Pancham once I came away. What transpired between the two, there was no way of knowing, but evidently RD had a hard time convincing Lata that it was he who had invited me for a musical tête-à-tête concerning Dada Burman.

As the Arjun dubbing began, I heard Pancham say, at one stage through the mike: ‘Didi, breathing zaraa control keejiye.’ Let me hasten to add – before you jump to conclusions – that this is a normal happening at any recording, whether the singer be Manna Dey or Lata Mangeshkar; Asha Bhosle or Mohammed Rafi; Alka Yagnik or Kumar Sanu. At all times, the singer has to be vocally so guided by the music director. It is a tribute to Lata’s recording discipline that she would let even a comparative junior like Pancham direct her thus. That is, if Pancham was indeed a junior still, for he was already 22 years into independent music direction by the mid-October 1984 stage. Once free, Pancham got talking:

‘It was Dada Burman who, from start to finish, shaped my music. No ordinary father was he. Any other father would have been highly disturbed to discover his only child devoting time to anything but studies for by then my failing in school was a recurring phenomenon. Kumar Shri Sachin Dev Burman was away in Bombay, carving out a musical career for him selfwhile, back in Calcutta, I was up to no end of pranks in the indulgent care of my naani [maternal grandmother]. Once as Dada and my mother Meera came to Calcutta, naani wailed: “He’s your son, take him away, I just can’t control him!”This was when Dada decided to take me to Bombay to prepare me for a career in films. “What is it you can do well, Pancham?”asked Dada. “I’m a good cyclist. I have even won a prize in a cycle race.” Dada’s reaction to that was telling: “I was a far better tennis player than you are a cyclist, still I didn’t seek a career in that particular sport. Be serious, Pancham, what is it you can do fairly well?” My response to that was: “I can play the mouth organ. I can play my own tune!”

‘“What do you mean – ‘play my own tune’? Let’s hear you play.” I played what I knew – with some unease. At nine years of age, I wasn’t such a kid as not to know how considerable was Dada’s reputation as a musician in Calcutta. He was not only hailed as a great composer but also as a great singer. So to play my puny mouth organ in front of him? But play I did. I had a bad habit even then, I tended to pinch tunes! So the tunes I played were all filched. Dada heard me out in seeming silence. “Pancham, what’s this you’ re playing?” he finally said. “Could you honestly call these tunes your own? Remember, originality is something you cultivate here and now or never. Banish these tunes from your mind. Good or bad, play your own tunes. Meera and I are going to Bombay tonight. We’ll be back in three months. Meanwhile, you will learn the tabla.” Taken aback, I couldn’t help exclaiming: “The tabla? What’s there to learn in the tabla?”

“‘Plenty! To be a composer the first thing you must develop is a sense of rhythm. Learn the tabla seriously and you will develop a sense of rhythm that is sure to stay with you throughout your composing life. While playing the tabla, whatever comes to your mind, try to turn it into some kind of a composition. Playing the tabla, Pancham, you will get ideas. Those ideas must be converted into tunes. About the quality of those tunes, do not bother at this stage. That you could do later.’”

Thus did Pandit Brijen Biswas become Pancham’s first teacher, initiating him into not only the basics of the tabla but all its intricacies. Later, RD came into contact with Pandit Samta Prasad, the virtuoso you hear playing the tabla in S. D. Burman’s Naache man moraa magan thig daa dheegee dheegee, the Raag Bhairavi classic rendered in the 1963 film Meri Surat Teri Ankhen by Mohammed Rafi to go on Ashok Kumar. Then Pancham was sent to learn the sarod from Ustad Ali Akbar Khan whom you hear in Dada Burman’s O jaane waale ruk jaa koee dam from Bimal Roy’s Devdas (released in January 1956). Here Pancham also came under the spell of the no less distinguished Annapurna, wife of sitar wizard Pandit Ravi Shankar. Thus did Pancham derive the advantage of a unique musical maahaul (atmosphere) in his formative years. ‘Dada’s idea in putting me in live contact with these performing greats,’ observed RD, ‘was to ensure that I got the benefit of the kind of musical “atmosphere”I just could not hope to have in the crassly commercial film industry of Bombay. Today, if I am asked to compose for a totally classical theme, I would be equal to the task for remember that R. D. Burman is not only all that jazz, all that disco. I love to compose a classical theme too,’ asserted Pancham with a certain pride for one habitually self-effacing.

A vital thing RD learnt from his father was that composing must be done each day, even if one had no film on hand: ‘If you compose five-six tunes a day, then you will find that you have at least one worthwhile tune at the end of the day.’ RD made his debut with Mehmood’s Chhote Nawab, way back in February 1962. After that he did Bhoot Bungla (1965) and Teesra Kaun? (1965), only to be jobless for a year during which he unfailingly composed five-six tunes a day. Only after razorsharp competition with first O. P. Nayyar and then with Teesri Manzil hero Shammi Kapoor’s favourite (Shanker-)Jaikishan did Pancham land that 1966 Nasir Husain show – the Vijay Anand-directed film arriving as an RD godsend. Pancham found that the tunes he had stocked, at Dada’s instance, helped him meet the demand on the spot as the real rush came after Teesri Manzil. Pancham also never forgot how – long before all this – as a teenager he had gone to see Dev Anand’s Funtoosh with its music scored by S. D. Burman, how shocked he had felt to find that one of his tunes figured in that 1956 Navketan film in the shape of Ae meree topee palat ke aa! He returned home, scandalized, only to be told by his father: ‘I know what you are going to say – that I have pinched a tune of yours. So I have. But you should consider that an honour, Pancham! If a tune of yours is good enough for me to flick, it means you have really come up with something. In any case, Ae meree topee is a light-comedy tune. The day I come to rate a more serious composition of yours as worth lifting, you would have truly arrived as a composer.’

‘Such a serious tune, a mood tune in fact,’ continued Pancham, ‘was S. D. Burman’s Hum bekhudee mein, superbly composed to go on Dev Anand in that [1958] Navketan film, Kala Pani. The opening passage was flowing ever so smoothly when Dada Burman, in that folksy tone of his, moved away from the mainstream with the “turn”of Dekha kiye tumhein hum ban ke deewaana. This was when Dada appeared to give the tune a bend that just didn’t blend! How to communicate that to a musician of Dada’s range and depth? As Dev Anand and I looked aghast at the incredible twist Dada was giving to such a flawless tune, director Raj Khosla, a singer himself, made bold to say that they, as a Navketan team, felt SD was ruining a beautiful tune by introducing a passage that sounded off-track. This was when Dada lost his cool and, turning to me, said: “You want to be a composer, don’t you, Pancham, and you too think that this turn I’m giving to the tune isn’t blending, that it is off-track? I’m disappointed in you, Pancham. Just all of you see how I get Rafi to blend it in the final recording!” Blend that turn-in-tune did via Rafi – ever so beautifully, which proved that SD had an audio-visual mind, for he could envision “a tune within a tune”. That was the moment when I realized how much I still had to absorb from Dada as a would-be composer.

‘Another thing I learnt from Dada is that it’s better to be plain speaking to avoid any chance of a misunderstanding later. Dada was never wishy-washy. Take the time we recorded Chal ree sajnee as a “backdrop” number for Raj Khosla’s [1960] film Bambai Ka Babu. I felt the tune was ideally suited to the vocals of my resonant pet then, Hemant Kumar. But Dada firmly ruled him out, saying his vocals had begun deteriorating. Manna Dey was considered next, but Dada felt that the tenor of the Chal ree sajnee tune just would not suit his voice. Talat Mahmood was rejected instantly by Dada on the ground that too much “vibration” had crept into his voice. If Kishore Kumar had the vocals to go with the tune, Dada shrewdly sensed that he would not be overkeen to perform in a “backdrop”number, since the main playback performer, on Dev Anand in Bambai Ka Babu, was Rafi! That is how Mukesh came into the picture, though Dada agreed to test him rather reluctantly. Upon that genial singer’s arrival for rehearsal at our Sion-Matunga residence, Dada frankly told him: “Look, Mukesh, I can’t promise that I would retain your voice in Chal ree sajnee. If after rehearsal, in the final take, I find your rendition to be unsatisfactory, I retain the right to scrap the song!” Mukesh’s response: “But you always have that right, Dada. All I know is that you have called me to sing again for you after some 12 years, so trust me to put in my best. After that, as the song’s composer, it’s your privilege to retain or reject me.”

‘S. D. Burman bowed to no singer,’ continued Pancham. ‘When he felt that Kishore was, for whatever reason, not giving cent per cent, he turned to Rafi – on Dev Anand – with a total lack of inhibition. When he brought back Kishore, he did so on his own terms. Same was the case, I remember, with someone so mighty as Lataji. Cleverly, Dada used me as a ploy to get back a Lataji he was missing all the time in his music – through the late 1950s into the early 1960s.’ (Lata, after Paying Guest – 1957, resumed singing for Dada Burman with Bimal Roy’s Bandini in 1963 via Jogee jab se tuu aayaa mere duaare on Nutan.) ‘As it turned out,’ went on Pancham, ‘Lataji too was quite keen to get back into Dada’s music room. This Dada sensed only as Lataji arrived, some time in June 1961, to record Ghar aa jaa ghir aaye for me in my debut film Chhote Nawab.’

It was again from his father that Pancham learnt how to draw the best out of Kishore. ‘Dada’s technique,’ pointed out Pancham, ‘was to send the tune’s spool-tape in advance to Kishore. He sounded peerless, once this spool-tape was made available to him beforehand. There and then I decided that Kishore would be my first choice as a singer, once I had the freedom to pick my own voice.’ Pick Kishore RD did – to some cult effect through the 1970–87 span! So much so that, once Kishore was gone, even a Kishore replica like Kumar Sanu would do, such was the intrinsically Rabindra Sangeetized quality of R. D. Burman’s posthumously lingering music – allied to Javed Akhtar’s inspirational poetry – in Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s 1994 biggie: 1942: A Love Story. Once in a lifetime does a performing pair (Manisha Koirala and Anil Kapoor) have the great good luck to get as many as half a dozen songs revolving around their screen personae. From Kumar Sanu’s Ho ek ladkee ko dekhaa toh aesaa lagaa, to Kuchch na kaho kuchch bhee naa kaho, to Rooth na jaanaa tum se kahoon toh; from Kavita Krishnamurthy–Kumar Sanu’s Rimjhim rimjhim rumjhoom rumjhoom bheegee bheegee rut mein, to Kavita going so impactively on Manisha as Pyaar huuaa chupke se, Rabindra Sangeet was the base and Pancham the tuneful talisman. Even Shivaji Chattopadhyay’s Yeh safar bahut hai katheen magar naa udaas ho mere hamsafar (Jackie Shroff singing with Manisha Koirala around) was effective on the screen. The only sore spot was Lata’s deplorably flawed rendition of Kuchch na kaho (as ‘voiced over’ on Manisha) towards the film’s end but, since this recording took place after his death, Pancham is not to be held responsible for it. Lata came to dub the Kuchch na kaho number after the Kavita Krishnamurthy & Chorus original had been already recorded for the film in the voice of that singer – a singer our diva (to spite Vani Jairam) unfailingly ‘dubs’ as rating among the best after her!

Kitnee akelee … Dada Burman used Pancham to get back Lata

It is well to remember that, while R. D. Burman is adored today, he had, after a full 30 years in films, few takers in our supinely commercial film trade by the time he came to doing 1942: A Love Story. This 15 July 1994-released film by Vidhu Vinod Chopra brought Pancham posthumous immortality, true, but even R. D. Burman was clearly beginning to slip – at best maintaining a toe-hold – once A. R. (Roja) Rahman happened in the early’ 90s. A. R. Rahman proved ‘instrumental’ in posing a challenge to R. D. Burman on his own orchestrating turf. Pancham, after having been witness to a film era (1962–93), instinctively divined the magnitude of the threat when someone came along saying that R. D. Burman remained his chief inspiration! Therefore, Pancham went when the going was good, unkind as that might sound at first hearing. Could not 1942: A Love Story possibly have arrived to mark an S. D. Burman-Aradhana scale of comeback for R. D. Burman, had he lived on beyond 4 January 1994?

On the contrary, I submit that 1942: A Love Story acquired such a rare musical value (for listeners of all ages) only because Pancham passed into iconic history when he did. For his genuine fans, the movie and its music carried a matchless sentimental value. For old stagers, who swore by the father, 1942: A Love Story was proof positive that the son was no less adept at exploring the finer tones of Rabindra Sangeet. Pancham, never forget, was groping for a musical posture by the time he was no more and, therefore, no less. By then, ‘Burman The Second’ had left his imprint on Hindustani film music as an art form that could be divorced from mindless commerce.

As Pancham once told me, the senior Burman had vision. He instinctively sensed that music was in his son’s blood. Yet not once was he soft with him as his ‘first assistant’. In fact, more than once, he harshly pulled him up in the presence of everyone. ‘It hurt like hell at the time, but I saw there was merit in Dada’s argument that he was dealing with his chief assistant, not his son, each time he spoke to me sharply,’ conceded Pancham. It was SD’s rounding that equipped Pancham for the job and, when the time came for R. D. Burman to compose all by himself, the father just let him go, saying he had nothing left to teach him. After so releasing him to fend for himself, SD said he loved his son’s music in Amar Prem. ‘This [1971] film is my mummy Meera’s favourite too,’ recalled Pancham. ‘I remember Mummy telling Dada as my tunes in Amar Prem clicked big: “After all, whose son is Pancham?”’

Never could I forget how, once son Pancham came to be summarily eliminated as his first assistant, SD chose wife Meera Burman for the job in Goldie Vijay Anand’s Tere Mere Sapne (1971). Why did SD not offer the job to one of his two main assistants Basu or Manohari? Pancham himself answered this teasing query when I pointedly asked him as to why Laxmikant-Pyarelal always managed to be one box-office notch up on him. ‘But they are two!’ argued Pancham. ‘They can always have a one-to-one, heart-to-heart discussion about what exactly to do. I can’t have a similar face-to-face talk with Basu or Manohari. An assistant is an assistant – “under you”always. While Pyare just tells Laxmi off.’ In this respect, Dada Burman was far savvier, looking at the way he used Pancham all he could – as ‘first assistant’. The moment Pancham’s commitment became doubtful, SD chose to jetti son him, even while retaining Basu– Manohari’s services. Yet the new job of ‘first assistant’, to everyone’s surprise, went to wife Meera Burman. SD, as a good tennis player, was on the ball in so moving to the net. Remember what happened to Sapan Chakravarty (with Basu-Manohari for his assistants) after he had scored (for late-March 1975 release) B. R. Films’Zameer (Shammi Kapoor, Saira Banu, Amitabh Bachchan, Vinod Khanna – special appearance)? Sapan, after that 1975 experience of working with Sahir Ludhianvi, chose to return as Pancham’s assistant. ‘I feel happier serving Pancham,’ Sapan told me, simply.

Madan Mohan brought down the baton deadly straight when he said: ‘Pray, what’s an arranger but a glorified steno? He just takes down the musical notes I dictate!’ But Laxmikant-Pyarelal boldly quit being ‘arranger assistants’ as they broke through with Parasmani (1963) –with Hanstaa huaa nooraanee chehra; Roshan tumhein se duniyaa; Woh jab yaad aaye bahut yaad aaye; and Choree choreejo tumse milee toh logkyaa kahenge. All leftover money, still accruing from assistantship, the neo-duo, farseeingly, invested in self-promotion. Laxmikant picked up all the tricks watching Jaikishan. As Shanker-Jaikishan chose to break with J. Om Prakash after Ayee Milan Ki Bela (Rajendra Kumar-Saira Banu-Dharmendra, 1964), following a price-jacking dispute, Laxmikant-Pyarelal were right there to do Aaye Din Bahaar Ke (Asha Parekh-Dharmendra, 1966). Nor did LP stop with doing a tunefully swell job here. They persuaded J. Om Prakash to offer a complete set of Aaye Din Bahaar Ke records to each one present at the movie’s press show. Thereby playing on J. Om Prakash’s sentiment of wanting to ‘show’ Shanker-Jaikishan their place. I never met anyone more honey-tongued than Laxmikant. I doubt if Pancham (as S. D. Burman’s immediate deputy) learnt anything, in this vital direction, from Laxmikant – his first assistant, once, on his maiden movie: Chhote Nawab (1962).

Nor did Dattaram (Wadkar) pick up much from being Shanker-Jaikishan’s first assistant for so long. It is not enough that a Dattaram creates something so engrossing (in Raag Yaman) as Mukesh’s Aansoo bharee hai yeh jeevan kee raahein to go on Raj Kapoor (vis-à-vis Mala Sinha) in Parvarish (1958). As you so create, you need to grow out of the first-assistant syndrome. Laxmikant-Pyarelal swiftly put their assistantship-past behind them. Others, like Dattaram and G. S. Kohli (O. P. Nayyar’s permanent assistant), did not have the courage to do so. Ghulam Mohammed, for one, chose to remain Naushad’s chief assistant even while scoring (through three years) the music for a clutch of films in his independent name. Before Naushad came to doing Baiju Bawra (released October 1952), he let a fretting Ghulam Mohammed go, bringing in, as his new chief assistant on Baiju Bawra, the man’s brother, harmonium ace Mohammed Ibrahim. This was the musician set to play the harmonium so surpassingly in that rapturous Raag Shahana qawwali by Rafi, Bande Hasan, Mubarak Begum & Chorus, Mahalon mein rehne waale humein tere dar se kyaa, in M. Sadiq’s Shabab (1954).

The ones really to challenge Naushad’s No. 1 standing, after C. Ramchandra, were SJ. Jaikishan’s premature demise on 12 September 1971 – to a Radio Ceylon accompaniment of Zindagee ek safar hai suhaana (from Andaaz) – found Shanker under unprecedented pressure to deliver during the last quarter of that make-or-break year. Only SJ’s Andaaz (Shammi Kapoor, Hema Malini, Rajesh Khanna) and Main Sunder Hoon (Mehmood, Leena Chandavarkar, Biswajeet) had made the 100 days’ run-cut (that year) by the time Jaikishan was no more. SJ’s two prestige Shammi Kapoor starrers, Jane Anjane (with Leena Chandavarkar) and Jawaan Mohabbat (with Asha Parekh), had both fizzled out, underlining the Rebel Star to be nearing the end of his insouciantly flamboyant stay at the helm. Add to that five damp squibs in Albela (Mehmood, Namrata, Anwar Ali); Balidaan (Saira Banu-Manoj Kumar, Bindu); Seema (Simi Garewal, Kabir Bedi, Bharti, Rakesh Roshan); Duniya Kya Jaane (Bharti, Premendra, Anupama); and Yaar Meraa (Raakhee, Jeetendra, Nazima) and you see how the year proved cataclysmic for SJ. All the more so as there was by way of a December 1971 release – days before war broke out between India and Pakistan – that shock ‘setback-to-come’ in the shape of RK’s Kal Aaj Aur Kal (Prithviraj, Raj Kapoor, Randhir Kapoor, Babita). Thus did our most durable duo’s melodious 20-year reign – starting with Awaara in December 1951 – draw to an end. Come 1972 and Shanker-Jaikishan ceased to be numero uno.

Even as SJ fell, Laxmikant-Pyarelal spectacularly consolidated their gains –with three mega-hits, during 1971, in Haathi Mere Saathi (Rajesh Khanna, Tanuja); Dushmun (Rajesh Khanna, Mumtaz, Meena Kumari); and Mera Gaaon Mera Desh (Dharmendra, Asha Parekh, Vinod Khanna, Laxmi Chhaya). By contrast, the sturdy Kalyanji-Anandji duo – after having been second only to Laxmikant-Pyarelal till end-1970 (following Goldie’s Johny Mera Naam) – lost major ground, with only one 1971 major hit in Paras (Raakhee, Sanjeev Kumar, Farida Jalal) and just a middling success in Maryada (Raaj Kumar, Mala Sinha, Rajesh Khanna). Also, S. D. Burman’s Naya Zamana (Hema Malini, Dharmendra) and Sharmeelee (Raakhee, Shashi Kapoor) emerged as top 1971 musical hits. Dada Burman’s Gambler (Zahida, Dev Anand, Zahirra) and Tere Mere Sapne (Mumtaz, Dev Anand, Hema Malini), too, won tuneful acclaim. This was the signal for RD to begin his neo-phenom advance to the No. 2 spot, as Amar Prem (Sharmila Tagore, Rajesh Khanna) arrived, by end-1971, in the wake of Hare Rama Hare Krishna (Mumtaz, Dev Anand, Zeenat Aman) with its Dum maaro dum Asha–RD hotline. In between those two attention grabbers, Pancham had Nasir Husain’s Carvaan (Asha Parekh-Jeetendra-Aruna Irani) making 1971 waves all its own. Thus, from 12 releases during 1971, Pancham had three huge hits. With O. P. Nayyar losing out even before SJ, the end-1971 field was wide open. But R. D. Burman – at a point, mind you, when ‘Panchamania’ had already gripped a whole generation – just did not have it in him to play Laxmikant-Pyarelal at their Filmfare award-lifting game.

Pancham buffs might hate to hear this, but the sad truth is that their pet composer answering to the name of R. D. Burman never really overtook Laxmikant-Pyarelal in the box-office stakes. LP, with 15 films against SJ’s 16 during 1971, snazzily rose to No. 1 by 31 December 1971, never really to surrender that enviable box-office niche right through the decade (till end-1980). Though Pancham, single handed, went on to score music for as many as 331 films in 32 years (292 in Hindi, 31 in Bengali, 8 in other languages), his dilemma was that he just did not know how to sell himself as a neo-brand even when he had the cutting edge on the Laxmikant-Pyarelal twosome, following the advent and success of Kati Patang (Asha Parekh, Rajesh Khanna, 1970). In those 331 films, while Kishore Kumar sang, for R. D. Burman, 558 songs (227 solo, 245 duets, rest with others), Asha Bhosle rendered no fewer than 840 of Pancham’s compositions (406 solo, 338 duets). Compare that with the Lata–RD combo’s tally of 363 songs (194 solo, 147 duets). If the next female highest is Kavita Krishnamurthy, it is so with but 35 songs (12 solo, 13 duets)! Even Mohammed Rafi, hold your breath, flaunts a tally of 120 Pancham songs (41 solo, 53 duets)! Easily exceeding Rafi, astonishingly, is Kishore’s son, Amit Kumar, with a round 150 songs (54 solo, 61 duets). Next highest, after Amit and Rafi (from singers male and female), is one R. D. Burman (under the baton of R. D. Burman) – a total of 106 songs (40 solo, 36 duets)! To think that Manna Dey rendered but 59 songs (21 solo, 14 duets) for Pancham.

A loner all the way was Pancham, even after Asha Bhosle came into his life (on 7 July 1979) as his comprehending wife – more mature as one conceding years to RD. After those long years during which she had thoughtlessly let O. P. Nayyar rule her life, Asha began to grasp market trends. This while, all along, RD rested on his trendsetting oars, happy only among his own select group of hangers-on, much to Asha’s chagrin. The fact is that R. D. Burman waited for things to happen. Never ever venturing to make things happen. Even on the more artistic side of commercial cinema, Pancham needed Gulzar to make things happen. The two represent a team whose oeuvre yielded us a lyrical-musical repertoire falling into a calibre all its own. Take Gulzar’s very first song while teaming with Pancham– how it absorbs you in Kishorean tones of Musafir hoon yaaron naa ghar hai naa thikaana (on Jeetendra in Parichay, 1972). Compared to Kishore, Bhupendra might be a singer at the other extreme, yet audio-vision, in Parichay, how Gulzar-Pancham bring him to us in a mood of Mitwaa boley meethe bain (on Sanjeev Kumar). As for the super Lata–Bhupendra Parichay duet (on Jaya Bhaduri-Sanjeev Kumar), did even Anil Biswas ever accent the subtle shades of Raag Bihag better than does Pancham in Beetee naa beetaaee raina? Finally, Saa re ke saa re (by Asha-Kishore-Sushma & Chorus) is the liltingly light foil to the rest of the Parichay score upholding Gulzar-Pancham as a team to watch for quality scoring in the years to come.

That it took the twosome three more years to get together sounds incredible, yet the plus side is that Gulzar-Pancham teamed in not one but two films during 1975: Aandhi and Khushboo. Some Gulzar–RD get-together Aandhi remains! Even as Suchitra Sen and Sanjeev Kumar make the film their acting touchstone, Pancham-Gulzar are there on this pedigree pair – tranquilly musically – via Lata-Kishore in a vein of Eis mod se jaate hain; Tum aa gaye ho noor aa gaya hai and Tere bina zindagee se koee shikwaa toh nahein. If Suchitra-Sanjeev were histrionically made for each other in Aandhi, the film is also the ultimate tribute to the Gulzar–Pancham team’s tuneful togetherness. Who cares for the political undertones of Aandhi so long as it is Gulzar-Pancham making its music in an idiom identifiably their own? Later in the same 1975 year came Khushboo with a rare musical flavour. If Jeetendra here was a diametrically different actor under Gulzar, so was R. D. Burman a dynamically different composer in that writer-director-lyricist’s cozy company. Pancham– Gulzar’s Khushboo lovelies – like Do nainon mein aansoo bhare hain (Lata on Hema Malini); Bechaara dil kyaa kare (Asha on Farida Jalal); Ghar jaayegee tar jaayegee (Asha on Hema Malini); plus O maanjhee re apnaa kinaara nadiyaa kee dhaara hai (Kishore on Jeetendra)–made this Hema Malini–Jeetendra starrer a musical show to treasure.

Bechaara dil kyaa kare …At her Peddar Road residence, Asha Bhosle

celebrates her birthday as ‘Liberation Day’ from O. P. Nayyar –

(L to R): Yogi, Shatrughan Sinha, Anil Dhavan, Vijay Anand,

Asha Bhosle, Panchamand Varsha (Asha’s daughter)

Pancham–Gulzar’s Kinara (1977), with Hema Malini’s dancing for its leitmotif, had our celeb writer-director-song writer holding the musical scale even between Dharmendra and Jeetendra. On the one hand, we had Bhupendra going on Dharmendra in a freewheeling Hema-romancing hue of Ek hee khwaab kaein baar dekha hai maine. On the other we had Kishore – RD-resonant as ever – coming through on Jeetendra as Jaane kyaa soch kar nahein guzra/ek pal raat bhar nahein guzra. But nothing to Kinara-touch the Lata–Bhupendra duet to recall, now and forever, as Naam gum jaayegaa chehraa yeh badal jaayegaa (on Hema Malini-Jeetendra). Such is the abiding aura of this Kinara duet that even Meethe bol boley boley paayaliyaa – if a song in a different genre altogether – suffers when a comparison is drawn, well as Bhupendra renders this one, too, with Lata and Swapan (on Jeetendra, Hema Malini and Dr Shreeram Lagoo). Completing a standout Pancham–Gulzar Kinara score is the pleasing Ho ab ke naa saawan barse (Lata on Hema Malini). If there is a mixed viewpoint on Bhupendra’s true niche as a hero-material singer, it just does not apply in the case of a Gulzar– Pancham package. In fact, the way Bhupendra ‘nuanced’ his vocalizing in Pancham–Gulzar films, you genuinely wondered why he went no further as a singer with a voice distinctively his own.

If Namkeen (1982) as a movie saw Gulzar at his cinematic best, its RD music part, for once, fell short in terms of expectations habitually raised by the team. Only Kishore’s Ho raahon pe rahte hain yaadon pe basar karte hain managed to leave an impress – on Sanjeev Kumar driving that truck through such sylvan surroundings. Namkeen certainly came as a Gulzar–Pancham tuning letdown after a sustained lyrical-musical treat in the first five years of a 10-year span (1972–82) – a treat made up of Parichay, Aandhi, Khushboo, Kinara, Angoor and Kitaab. In such a milieu, it is a measure of Gulzar–Pancham’s lyrically creative artistry that you are still left wondering if, in terms of not just cinematic intensity but tuning integrity as well, Izaajat (1987) is not the twosome’s awesome best. Naseeruddin Shah, Anuradha Patel and Rekha, they ‘live’Ijaazat – so do Gulzar and Pancham harmonize with those three in tones tender as tender could be. Asha Bhosle–National Award winningly – articulating Anuradha Patel as Meraa kuchch saamaan tumhaare paas padaa hai is a tear-wrenching visual designed to hold you in bondage for a lifetime to come. What vocal elasticity of expression by ‘Meraa Kuchch’ Asha here! Maybe Pancham had a point when he asked Gulzar to bring him – for tuning – the latest 8-column banner headline (from The Times of India), when that song conjuror went up to him with the metreless Meraa kuchch saamaan tumhaare paas padaa hai! That Pancham could set to heart-holding tune such an indisciplined piece of Gulzar ‘poetry’ is a pointer to his composing impulses being as flexi as the vocals of Asha by 1987. Even Qatraa qatraa miltee hai qatraa qatraa jeene do zindagee hai – representing the other Ijaazat facet of Pancham-Gulzar – has its own flowing charm as it unveils on Rekha. No less Ijaazat-telling is Gulzar– Pancham’s vibing with Asha, on Rekha, in a hue of Khaalee haath shaam aayee hai khaalee haath jaayegee. On the Ijaazat face of it, a theme offering so little scope for tuning insights, the film is memorable, yet, for the musical impact Asha-Pancham-Gulzar leave on viewers having their eyes, otherwise, riveted on Rekha-Naseer-Anuradha.

How would Pancham-Gulzar have fared with the never-made Devdas starring Dharmendra (in the title role), Hema Malini (as Parbati by Gulzar dispensation), Sharmila Tagore (as Chandramukhi: clearly Gulzar expecting her to take up where she left off in Mausam, 1975) and Dr Shreeram Lagoo as Chuni Lal? Try and get hold of the two Gulzar–Pancham ‘wist fuls’ recorded for this Devdas before the project came to be shelved – Bhupendra’s Sehmaa sehmaa daraa-sa rehtaa hai jaane kyun jee and Lata’s Kuhoo kuhoo kuhoo koyaliyaa bulaaye ambuaa taley. His 1962 Lata-sung first film Chhote Nawab – given such an inventive backdrop – would Pancham still rate it as his best ever score? I had pointedly asked RD as I met up with him in his ‘Marylands’ santa Cruz North Avenue music room (on the Saturday of 22 October 1983): ‘I do, if only because Lataji was not, any longer, singing for Dada [Burman] and, those days, you were “made”if you got Lataji to render your maiden song. Astonishingly she readily agreed to sing my Raag Malgunji creation, Ghar aa jaa ghir aaye. The memory of the legendary Lata Mangeshkar consenting to sing so readily for a beginner like me makes Ghar aa jaa and, with it, Chhote Nawab unique.’

‘There were,’ I point out, ‘those three Lata–Rafi Chhote Nawab duets: Aaj huuaa meraa dil matwaala; Matwaalee aankhon waale; and Jeene waale muskuraa ke jee. Today you openly say you never did care for Mohammed Rafi. But, at the mid-1961 Chhote Nawab song-recording stage, you must have felt grateful to have had our No. 1 male singer as your playback performer?’ To that, Pancham responds: ‘No doubt Rafi was No. 1 then, but I myself had rehearsed him often enough – for Dada Burman – to know that I could go along with him so far and no further. It was so tough to get Rafi to amend something you had already taught him. Take my [1966] breakthrough Asha–Rafi Teesri Manzil duet, Aa jaa aa jaa – Rafi just was not able to grasp its finer points. How Rafi struggled as Asha so exemplarily stretched the critical Aa aa aa aa jaa, Aa aa aa aa jaa, Aa aa aa aa jaa, aaa… notes. Kishore would have latched on to it in a trice!’

‘Easy to say that 22 years after it happened,’ I tried to corner Pancham. ‘The fact remains that, like C. Ramchandra, you made use of Rafi to further your career before categorizing him as the lesser talent compared to Kishore. Didn’t it happen because you were never patient with Rafi – like O. P. Nayyar was with Asha – to be able to draw striking results from the man who so feelingly sang for you in Teesri Manzil – to go on Shammi Kapoor – Tum ne mujhe dekhaa ho kar meherbaan and Deewaana mujh sa nahein is ambar ke neeche?’ Pancham, somehow, remained unimpressed: ‘Only I know how I got Rafi to do those two numbers. No matter how patient I was with Rafi, he lapsed into the same frame of vocal error, time and again. You had to teach Kishore just once and he was on to it like a shot. See the feel Kishore brought to my Chingaree koee bhadke in Amar Prem, how he made it sound as if he was singing it for you and you alone!’

Tum aa gaye ho noor aa gayaa hai …

Pancham says he spot-tuned with Gulzar

I could have pointed out to Pancham that there were also, from Nasir Husain’s 1977 Hum Kisise Kam Naheen blockbuster, such Majrooh written cult hits for RD as Kyaa huuaa teraa waadaa (Rafi with Sushma Shreshtha); the qawwali going gung-ho as Hai agar dushman dushman (Rafi with Asha, Swapan & Chorus); Yeh ladkaa haaye Allah kaisa hai deewaana (Rafi with Asha); plus Chaand meraa dil chaandnee ho tum (Rafi & Chorus). But you could reason on Rafi with Pancham only up to a point, since he had a near closed ear in the matter. So I let the Kishore– Rafi matter rest there. Changing tactful track, I asked: ‘Which is the first interlude piece you, R. D. Burman, did for an S. D. Burman tune?’ Pancham: ‘It is the Pyaasa [1957] interlude music you hear on Waheeda Rehman via Geeta Dutt in Jaane kyaa tuu ne kahee.’ To my next point, about whether Dada Burman himself ever sang playback for Dev Anand, Pancham replied: ‘Yes, it is Dada you hear in the Dhhaa dhhaa part of the Asha Bhosle rendition, Dil lagaa ke qadar gayee pyaare, on Nalini Jaywant in Kala Pani [1958].’ Thus far Pancham is forthcoming. But the moment a yesteryear-hooked fan presumes to devalue the music of the 1990s, Pancham is up in arms, thundering: ‘What do you mean, nothing worthwhile is being composed today? Even better music than in Dada Burman’s time is being composed today!’ It is never a good idea to ask the son to experience, live, his father’s music. At some stage, the composer in the lad has to act up. I therefore wait for Pancham to cool down for him to be able to tell us: ‘Take Dada Burman’s roughly 40-year-old Hans le gaa le dhoom machchaa le duniyaa faani hai choral number from Jaal that you just played. The tune’s orientation is totally Goan, yet in the Kaisee yeh jaagee agan interlude, suddenly, you hear a snatch of Rabindra Sangeet! I pointed this out to Dada and to his assistant (N. Dutta from Goa). But who would listen to a kid like me in 1952?’ ‘How,’ I ask Pancham, ‘did Dada Burman take to Guru Dutt’s inviting you to score for his Raaz when you were barely 18 years old?’

Meree aawaaz hee pehchaan hai … Lata-Pancham vibing

‘Dada didn’t like it one bit!’ revealed Pancham. ‘He felt Guru Dutt was spoiling me by giving me a break so early in life. But Guru Dutt had been impressed by the extent of my contribution to the musical moulding of his Pyaasa theme, as scored by Dada Burman – with Sar jo teraa chakraaye my brainwave. Raaz came to be abandoned after five reels were shot,’ went on Pancham. ‘During its making, Guru Dutt, a highly whimsical person, drove me up the wall. He might have known what exactly he wanted, as his imagination took wings. But the idea remained in his mind, in his eye – the thing he precisely wanted never was clear to me, as the Raaz composer. Guru Dutt would okay my tune one morning, arbitrarily reject it the day following.’

‘But you were able readily to satisfy the equally demanding Raj Kapoor on the theme song of Dharam Karam, weren’t you?’ I point out. ‘Raj Kapoor came as a pleasant surprise after Guru Dutt,’ reminisced Pancham. ‘Dharam Karam came to me through son Daboo [Randhir Kapoor] with whom I generationally tuned. Raj Kapoor had outlined the situation so clearly to me that I was hopeful. Yet fearful. For what it was worth, I played the first of six tunes I had prepared for him, as Raj Kapoor sat hoveringly in front. I had barely started playing my first dhun when Raj Kapoor burst out: “Situation ke liye perfect tune hai! Chalon, okay – bottle kholo!”Not only that, Raj Kapoor proposed a toast to me for the way I had composed what became – as Majrooh Sultanpuri wrote-to-tune – Eik din bik jaayega maatee ke mol, jag mein reh jaayenge pyaare tere bol. Exulted Raj Kapoor by way of an added bonus: “Hit gaana hai, shabaash, bete!”’

Meera Burman felt vindicated that her son had ‘done it’ in front of such a testing musical idol as Raj Kapoor. Even more fulfilled did she later feel upon viewing Dharam Karam (mid-December 1975) and experiencing how well Pancham had got Mukesh, on Raj Kapoor, to render Eik din bik jaayegaa in an RK film releasing within weeks of Dada Burman’s death. As a melodious singer herself Meera Burman did such a splendid first assistant’s job on Tere Mere Sapne that SD never really missed Pancham. Meera, first, ably rehearsed Lata for such indigenous Neeraj-written Dada tunes as Jaise Radha ne maala japee Shyam kee and Meraa antar eik mandir hai teraa (both on Mumtaz), alongside Lata– Kishore’s Hey maine qasam lee, lee and Jeevan kee baghiyaa mehkegee (both on Mumtaz-Dev Anand). Each time we called on the Burmans at ‘The Jet’, my wife and I found Meera to be a picture of grace and the perfect hostess. The Burmans’ princely background did we feel in the genuine warmth they brought to receiving us and making us feel wanted all the way. Before one of our visits – with O. P. Ralhan’s Talaash, the Sharmila Tagore–Rajendra Kumar starrer, just released late in 1969 – Dada wanted to know (on the phone) how we had liked the film’s music. I had truthfully found the music to be excellent and said as much, first, to Dada and then to Meera. That evening at ‘The Jet’, Meera first sang, for us, Khaayee hai re hum ne qasam sang rehne kee, followed by Kitnee akelee, expounding the delicate shades of those Talaash tunes, as bevelled and hewn by Dada for his Lota. Next Meera warbled, Aaj ko junalee raat maa, elaborating upon its folksy content. ‘Dada, I seem to have heard this before!’ I exclaimed. ‘Isn’t Aaj ko junalee raat maa drawn from your Eik baar tuu ban jaa meraa o pardesee phir dekh mazaa – sung by Shamshad Begum in Filmistan’s Shabnam, nearly 20 years ago?’ As Meera fidgeted, Dada simply pretended he had not heard. That way SD masterfully knew how to use age to his advantage! Later, when Vijay Anand’s Tere Mere Sapne collapsed at the box office, as Dada rang yet again – I sought to reassure him: ‘Your Tere Mere Sapne tunes are among your best, Dada.’ But Dada would not buy that line. Dada’s discomfiture clearly stemmed from the fact that this was his first film without Pancham– to whom he had wanted to prove a ‘chief assistant’ Meera point.

Pancham’s triumph and tragedy lay in the fact that (by end-September 1969) SD had a second coming with the very film, Aradhana, whose music RD had helped his father complete. From the moment Aradhana emerged as a musical rebirth for SD, Pancham knew it was ‘Now or Never’. His ceasing to be Dada’s chief assistant had followed months of turmoil at home. Both Meera and Dada were clearly worried, as Pancham returned late (from the disco) every other night. Neither Dada nor Meera could comprehend that it was inside the disco – during the small hours of the morning– that Pancham was picking up the upbeat notes he needed to give a Jawani Diwani turn to Hindustani cinesangeet. That Shakti Samanta’s Kati Patang (1970) happened to R. D. Burman almost alongside S. D. Burman’s Aradhana (end-1969) meant Pancham’s emerging as his own music man. So RD, from hereon, would take only so much from even SD. Meera gamely tried to shield her only child. But Dada was a ruthless disciplinarian at home – as in the music room.

I dare say the years separating Meera from Dada, both Meera and Dada from Pancham, had something to do with it all, following R. D. Burman’s first marriage (to the classy Gujarati Rita Patel in 1965) having failed. My wife and I recalled Meera’s introducing Rita as ‘our daughter’. Only for the marriage to go on the rocks. In such a setting, Meera, as RD’s anxious mother, was none too excited – at that 7 July 1979 point – about Pancham’s wedding an Asha Bhosle years older. The objection had something to do with lineage too. But Meera visibly mellowed upon discovering how diligently and comprehendingly Asha – despite being ultra-busy – looked after her Pancham. Meera had reason to feel relieved in the matter since Asha, by then, was crucial to the style of music that Pancham made. Some music the Burmans made between them– for Asha to help a distraught RD to ‘pick up the baton’ after SD’s death on 31 October 1975. The rest as they say is history – of how the Sound of Music came to be all but transformed in Hindustani cinema.

A rare combo it had been while it endured – SD and RD. By way of their fine-tuning, I rewind to the morning director Shakti Samanta arrived at the Burmans’ home, early in 1971, to brief RD on the first recording for Amar Prem. Dada too was there as Shakti outlined the song situation. To RD it appeared a stock situation for which he produced a stock tune. But Dada saw it totally differently and, when invited by RD to express his view, observed: ‘Your tune’s absolutely straight, Pancham, where’s the feeling in it? What if Shakti said a mere bhajan style of tune would do? You are a composer, Pancham, no mere tune manufacturer. How possibly could you place a bhajan style of tune on a prostitute, which is what Rinku [Sharmila Tagore] plays in Amar Prem? Do remember, she is no ordinary prostitute. This is a situation in which the woman is a mother first, a prostitute after. So the tune you compose, Pancham, must cinematically reflect – in each note – the prostitute’s mother instinct, which has been suddenly aroused by that child’s straying into what is forbidden territory for such a kid. The tune must have a rare sentiment, whereas your tune, if catchy, sounds routine to the composer in me, Pancham. It has taken no note of the prostitute’s instant urge to mother that child. You have, here, to be sensed as feeling, evocatively, for the mother in the prostitute.’

Ek main aur ek tuu … Meera

Burman ‘accepted’ Asha viewing

how she cared for Pancham

Saying which, on RD’s urging, SD took the harmonium and proceeded to modify the tune. He stayed (noted Pancham) within the same Khamaj thhaat, stuck to the same Raag Khamaj, while imparting a new feeling to RD’s tune. Of course the tune ultimately emerging (as RD duly admitted) was more of Dada than of Pancham, who had provided but the base tune. It was left to Dada Burman to give it a super-sensitive turn by which it unfolded in the heart-tugging manner it ultimately did (in Lata’s voice) on Sharmila Tagore – as Badaa natkhat hai re Krishna Kanhaiya kaa kare Yashoda maiyya ho.

‘In that moment I learnt from Dada that a composer’s job does not end with preparing a mundane tune for a situation mundanely outlined to him,’ confessed Pancham. ‘The music maker, as underlined by Dada, must get involved in the film’s script, study the character for whom he is composing and acquire the perception to project his composing personality into the character by venturing to experience her experiences. It was this one tune, as reshaped by Dada, that determined the tone I brought to the rest of the Amar Prem music through such numbers as Rainaa beetee jaaye [Lata]; Chingaree koee bhadke; Yeh kyaa huaa; and Kuchch toh log kahenge. The matchless vocals of Kishore Kumar did the rest.’

Could there be another Amar Prem, another Rahul Dev Burman? Only if there could be another Anand Bakshi to capture, in instinctive verse, the exact shade of emotion that Pancham wanted– so as to be able to weave his Raag Bhairavi magic on a Rajesh Khanna holding you in a trance, as Kishore Kumar inimitably immortalizes that superstar in a wispy mood of:

Maana toofaan ke aagey

Nahein chaltaa zor kisee kaa

Maujon ka dosh nahein hai

Yeh dosh hai aur kisee kaa

Manjhdaar mein nayaa doley

Toh maanjhee paar lagaaye

Maanjhee jo naau duboye

Usey kaun bachaaye

O.o.o.o. usey kaun bachaaye

Chingaaree…