Manna Dey is a singing giant and shall remain one. His inherent strength lies in the fact that no opponent could ever afford to take him vocally for granted. His virtuosity is such that Mohammed Rafi said it all when he noted: ‘You listen to my songs, I listen to Manna Dey songs only.’

The phenomenally versatile Manna Dey (born on 1 May 1919), whom S. D. Burman never considered as hero-playback material, today candidly admits that he was content to be second – now to Mohammed Rafi, now to Kishore Kumar, now to Mukesh. This however is not the Manna Dey I have known for nearly 50 years. It is not the Manna Dey speaking whose mood – each time I encountered him–was to get spotted as an indomitable performer, as one still in rousing confrontation with each one of his rivals. This is not the Manna Dey who once apprised me of how he had pointedly told R. D. Burman that the notion of his playing second fiddle to Kishore Kumar, in a classical stand-off, was just not on – not on even in a film. That was the 1968 Padosan hour in which Manna Dey, with becoming pride and no prejudice, rated himself as being inferior to none by training and temperament. But the Manna Dey of today presents a diametrically antithetic picture of the same Padosan confrontation with Kishore Kumar – as he writes in his book Memories Come Alive: An Autobiography (Penguin, New Delhi, 2007):

I was especially cautious when asked to sing for Mehmood in Ek chatur naar…with Kishore Kumar. To be put in the shade by Kishore’s flamboyant style of singing was a distinct possibility and, to counter the risk, I decided to work with R. D. Burman, striving to build on my strengths and find a way of holding my own. On the day we were to record Ek chatur naar, the entire staff at the studio stood outside the glass door to watch Kishore and me sing. For the two of us, the session had taken on the magnitude of a duel. It took us 12 hours – the recording started at 9.00 a.m. and ended at 9.00 p.m. – to complete it. And I must admit Kishore was in his element that day. Out of this tough battle to outshine one another would emerge a new star in the world of music.

For Manna Dey to have genuinely feared Kishore Kumar comes as a revelation; it flatly contradicts what he told me at the time. Here then was a man who hated being No. 2. But moving into 2007, going by the tone and tenor of his Autobiography published during that year, one is aptly reminded of what, in sport, is styled as the syndrome by which Nice Guys Finish Second – from the title given to his autobiography by B. K. Nehru (former ambassador to the USA and governor of states such as Assam, Gujarat and Jammu & Kashmir; and a cousin of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi).

That scale of a ‘nice guy’ I never ever found Manna Dey to be. In fact, the way Manna Dey set him self up in ceaseless competition has me recalling the attitude to combat of South African Kevin Curren. That fierce tennis opponent, after failing to get his ace service going for once in the 1985 Wimbledon final against Boris Becker, ended up remarking: ‘I’m no magician, you know, I can’t do it all the time.’ Queried next whether he was throwing in the tennis towel, pat came the Curren response: ‘Noway, this game is all about winning, the world has no time for losers.’ Perhaps a loser resigned to it – that he never was – is Manna Dey today. Or is it a compulsively mellowed man speaking who, with the years, has accepted that he always was a side show? The fact that this indomitable performer is the sole survivor– after Mohammed Rafi, Kishore Kumar, Hemant Kumar, Mukesh, Talat Mahmood and Mahendra Kapoor –must, understandably, make our singing atlas take a distantly tolerant view of high competition. Manna Day, a living legend approaching 88 years of age as he wrote his Autobiography, was looking back at a point in his career when even Mahendra Kapoor – as the lad who had accompanied him in Roshan’s all time 1966 Daadi Maa hit,Usko naheindekha humne kabhee– had not long to live. (Incidentally, Mahendra Kapoor, born 9 January 1934, passed away on 27 September 2008.) To this extent, one has to be comprehending in judging Manna Dey as he writes:

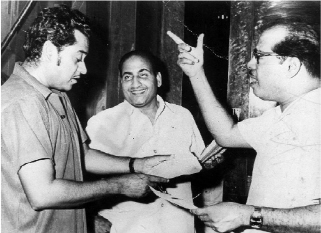

Each a rival: Kishore Kumar, Mohammed Rafi and Manna Dey

It is alleged that singers today are unable to stand the sight of their professional rivals – an attitude that never fails to surprise me, because none of my contemporaries ever felt that way about each other. We shared a healthy professional rivalry that had little to do with our personal equations. Outside the studio, we were the best of friends and shared our joys and sorrows with one another. I, for instance, had to work hard to get a foothold in the world of playback singing. But I never bore a grudge towards any of my competitors.

Is this strictly true? Were things really that hunky-dory? A certain fellow feeling among rival singers was always there but, beyond that, I found that they, for sure, could be pretty cutting in competition. Perhaps the fact that Manna Dey was never really in the running for the topmost playback position made him feel the loss less. To wit, when Talat Mahmood was No. 1 in the 1950–55 span, the Ghazal King was quite conscious about the unique position he commanded. ‘For all my forays into films as a hero,’ Talat told me, ‘I made it quite clear while turning a singing-star with A. R. Kardar’s 1953 film Dil-e-Nadan that I was still available to sing playback. But music directors just stopped ringing me, arguing that, since I was a performing film star, I wouldn’t have time to rehearse! At least for ghazals, they could have still thought of me. After all, there was not one singer to excel me, still, in this specialist field.’

There is an ego there, is there not? Likewise, Mukesh, if all things to all people in all seasons, was quite vocal about the way he was sidelined, in favour of certain rival singers, first by Naushad (after Mela, 1948, Anokhi Ada, 1949, and Andaz, 1949), then by Sachin Dev Burman (after Shabnam, 1949). This after a total of 17 super hits he sang for these two composers in those four films– 8 of those chartbusters on none other than Dilip Kumar. These are perennial hits worth recounting if only to spotlight one of the most blatant cases of vocal injustice meted out to a singer in the history of Hindustani film music. In J. B. H. Wadia’s S. U. Sunny-directed Mela(1948), spot-Mukesh hits on Dilip Kumarwere:Gaaye jaa geet milan ke plus those 3 duets with Shamshad Begum performing playback for Nargis: Dhartee ko aakaash pukaare; Main bhanwraa tuu hai phool; and Meraa dil todne waale. Next, in Mehboob Khan’s Surendra–Naseem starrer, Anokhi Ada (1948), Mukesh (working with the Naushad–Shakeel team) came up with 5 such hits, on Prem Adeeb, as Yeh pyaar kee baatein yeh safar bhool naa jaana; Manzil kee dhoon mein jhoomte gaate chale chalo; Bhoolne waale yaad naa aa; Kabhee dil dil se takraata toh hogaa (all four solos); plus the unforgettable duet with the inimitable Shamshad Begum: Bhool gaye kyun de ke sahaara lootne waale chain hamaara.

In Filmistan’s Shabnam (1949, heroine: Kamini Kaushal), all 4 song-hits on Dilip Kumar were by Mukesh – 3 of them with Shamshad Begum going as: Pyaar mein tum ne dhokaa seekha; Tumhaare liye huue badnaam; Tu mahal mein rehne waalee; plus (with Geeta) Qismat mein bichchadnaa thhaa. Side by side, in Mehboob Khan’s March 1949-released Andaz, we had that eternal Mukesh–Dilip Kumar foursome: Hum aaj kahein; Tuu kahe agar; Toote naa dil toote naa; and Jhoom jhoom ke naacho aaj. In sum, that makes it 4 Mukesh song-hits on Dilip Kumar for S. D. Burman in one film (Shabnam); and 13 song-hits (8 of them on Dilip Kumar), for Naushad, in three successive 1948–49 films. For Naushad and S. D. Burman to have summarily sacked Mukesh after this, was it not simply outrageous? What did you expect Mukesh Chand Mathur to do in the circumstances – show the other cheek on which Anil Biswas had once administered a resounding slap by way of a rebuke? ‘I just don’t want to talk about the recording promises these and other music directors made and never kept, opting for a fellow performer when each and every song I had sung for them, till then, had been a top hit,’ Mukesh told me, clearly feeling let down.

Rafi himself, after quite a struggle to reach the No. 1 notch, openly took on Lata Mangeshkar (no less) on the royalty issue. Even this, remember, was but the culmination of Lata’s losing her cool with Rafi, in front of all present, as the two failed, initially, to harmonize in a duet. I mean the 1961 dream Maya duet, Tasveer teree dil mein, finding Rafi feeling cut up upon music director Salil Chowdhury’s openly siding with Lata. Remember how Rafi even refused to sing for Khayyam when he felt that Mahendra Kapoor was being favoured by the composer? Hemant Kumar, for instance, once candidly told me that competing singers, growingly, got to replace him only because he had emerged as a serious rival music director to Naushad & co.: ‘Bombay music directors don’t like to see a singer, who has been performing for them, emerging as a competing composer in higher-budget A-class films. It’s not like in Bengal where we music directors – as singers too – invite each other to perform when we are composing. Ever since my Nagin emerged as a big-big hit and won for me the Filmfare Best Music award in the year 1955 [from Naushad’s Uran Khatola and Azaad of C. Ramchandra], top music directors, I found, began summoning me less and less to sing for them, even where my voice was clearly better suited to a song. Frustrating but true!’

Indeed, such gripes abound. Kishore Kumar, for all his sense of fun, was not exactly amused when S. D. Burman substituted him with Rafi on Dev Anand. Was then Manna Dey himself without any plaint against anyone? By no means. After drawing very close to Shanker, Manna Dey naturally felt it keenly when SJ began to turn to Mukesh in even non-Raj Kapoor films. This after Manna Dey, at last, had proved himself as a romantic singer under Shanker-Jaikishan – on Raj Kapoor in Shree 420 (1955) with Dil kaa haal sune dil waala; Pyaaar huuaa ikraar huuaa; and Mud-mud ke na dekh). Next, on Shammi Kapoor opposite Mala Sinha in Ujala (1959), how tellingly Manna Dey scored as the hero’s voice with Suraj zaraa aa paas aa aaj sapnon kee rotee pakaayenge hum; Jhoomta mausam mast maheenaa; Ab kahaan jaaye hum and Chham chham lo suno chham chham. Manna Dey now says that both Rafi and Kishore Kumar always remained ahead of him simply because the two deserved to rate higher. Nowhere in his Autobiography does one get a glimpse of the Manna Dey who ceaselessly strove to forge ahead of Mukesh and Rafi, Hemant Kumar and Kishore Kumar, though Talat Mahmood he never could hope to neutralize, until the Ghazal King found himself being marginalized as a playback performer turned singing-star.

Why does Manna Dey today consistently underplay his own performing artistry – I wonder? He is a singing giant and shall remain one. His inherent strength lies in the fact that no opponent could ever afford to take him vocally for granted. His virtuosity is such that Mohammed Rafi said it all when he noted: ‘You listen to my songs, I listen to Manna Dey songs only.’ Even Lata is a Dey fan, the way she submits: ‘Mannada, your Kasme waade [on Pran in Upkar, 1967] has enchanted me, how did you manage to emote so well? The melody haunts me relentlessly.’ Yet we have Manna Dey, who brought such rare raagdaari to S. D. Burman’s Tere nainaa talaash karein jise (on Shahu Modak) in such a huge hit as Talaash (end-1969), hiding his light under a bushel, just so that his opponents’ candle might shine the brighter. Could it possibly be then that, even while giving the impression of being an implacable opponent, in his heart of hearts Manna Dey shied away from competition? How else do you explain the instance of Padosan (1968), when Manna Dey incredibly said that he felt scared of Mehmood-measuring up, classically, to Kishore Kumar ‘singing’ for a hamming Sunil Dutt? Is this the Manna Dey, you wonder, who was vocally as versatile as any singer and was singularly unlucky to finish second best –Dey in, Dey out? I say this in the context of Manna Dey noting that he first actually said ‘no’ to the idea of taking on Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, in 1956 Basant Bahaar competition, when summoned by composer Shanker to Raag Basant-compete, with that classical stalwart, in Ketakee gulaab juhee champak ban phoole. Manna Dey says he was mortally afraid of being beaten in Bhimsen competition. However, the fact is that Bhimsen Joshi himself was no less apprehensive of being beaten, given Manna Dey’s firm grip on classical film singing style and technique! Composer Shanker, for his part, well knew that there were certain vocal misgivings on both sides. This made it all the easier for him to balance out Manna Dey and Bhimsen Joshi. In fact, Manna Dey, as we find out, would have stayed out of it all but for his ever elegant and musically trained Keralite wife Sulochana’s telling him:

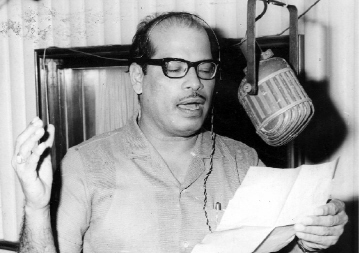

Ketakee gulaab juhee …Manna Dey held his own opposite Bhimsen Joshi

You must accept this offer. It’s a heaven-sent opportunity and under no pretext are you to let it go. You are well versed in classical music and singing that song (Ketakee gulaab juhee) will be no problem for you at all. What is more, the film’s hero (Bharat Bhooshan) will be singing the song on the screen and winning the singing contest, according to the script. So what is there to be afraid of? I am not about to accept your lame excuses. Go ahead and say ‘yes’. Take it as a challenge and try overcoming it. I am positive you will end up a winner.

Wife Sulochana’s faith in her husband’s singing powers helped Manna Dey (on Bharat Bhooshan) overcome Bhimsen Joshi (going on Parasram) in Basant Bahaar. The way Manna Dey, ultimately, took Ketakee gulaab juhee to a new Raag Basant high came as a mind-blowing revelation to viewer-listeners. No wonder Rafi once asked: ‘Dada, how do you manage to let your voice soar with such ease?’ This from a Rafi who, in the same Basant Bahaar, so compellingly competed with Manna Dey (both voices going on hero Bharat Bhooshan) via Duniya naa bhaaye mohe – as set against our classical champion’s Bhay bhanjanaa vandanaa sun hamaaree. Both were solos composed by Shanker who, when I asked him about the two singers performing similarly competitively in Seema (1955) on Balraj Sahni, had observed: ‘Manna Dey could not have sung my Kahaan jaa rahaa hai tuu, just as Rafi could not have rendered my Tuu pyaar ka saagar hai.’

Manna Dey (Probodh Chandra Dey in real life) started as an assistant to his composer-singer uncle, Krishna Chandra Dey. Once, in the case of a wonderful composition his uncle had been teaching Manna Dey with painstaking care, he told him: ‘I would like Rafi to sing this number, get in touch with him tomorrow and ask him to come for rehearsals till he has mastered the song thoroughly. Then we will record it.’ Manna Dey was crestfallen. ‘Why wasn’t Uncle allowing me to sing this fine composition when I could certainly sing it better than Rafi?’ he thought and unable to contain his feelings blurted out: ‘Can’t I be allowed to sing this song?’

‘Absolutely not! You can’t possibly sound like Rafi.’

‘I was heart-broken,’ says Manna Dey. ‘Rafi Miyan turned up next day and it was I who had to teach him the tune. Considering how I felt about the whole situation, it was terribly difficult for me, but there was no escaping the hated task. I was infuriated by what Uncle was putting me through. But, once Rafi started recording the song, I knew that Uncle was right. I had been quite mistaken, I could not have sung that composition better than Rafi – at least not at that time.’

Confidence personified one moment, a picture of diffidence the next, is Manna Dey. This as early as 1943, when Rafi, too, was a comparative fresher. It is perhaps the same approach that has Manna Dey saying in 2007, while touching upon Kishore Kumar’s advance with Aradhana (September 1969): ‘Rafi was, naturally, quite disheartened by the way he had been sidelined from his once prominent position. Had he come to terms with the capricious ways of a transient world and decided to be content with the public adulation he had once enjoyed, he would not, perhaps, have suffered quite so much over his rejection and ended up so bitter over the whole affair.’ But the point here is that Rafi, if momentarily displaced from his lofty perch, never ever gave up the fight. Such a no-quitting spirit, after all, is the sine qua non of high competition. Rafi knew that those Aradhana songs – each one of the 5 on Rajesh Khanna – had been his to sing, so long as S. D. Burman was in total charge. Kishore could occupy Rafi’s pre-settled Aradhana position only because Dada’s prolonged illness put R. D. Burman in total control. Rafi was a Singing Hercules when he fell with a thud. But unlike a Manna Dey reconciled, by then, to being sidelined, Rafi, after the end-1969 Kishore-Aradhana phenomenon, gamely uplifted himself afresh, to take a deep singing breath and compete anew with all the vocal resources at his command, undeterred by the Kishore Kumar–Rajesh Khanna odds being heavily stacked against him.

Rafi might or might not have regained his original prime position but he did demonstrate, to his fans numbering billions, that he still packed a punch in his vocals. This precisely is the hitback area – nay, the hitback arena – in which Manna Dey, loosening his hold on the mike, appeared to give up without a fight, once the Aradhana revolution turned out to be a bloodless Kishore Kumar coup. Manna Dey even rationalized such fresh competition by noting: ‘Kishore Kumar had a unique and unaffected style of singing which tended to eclipse the subtleties of classical music and place his singing partner in a duet at a disadvantage.’

By contrast, Rafi regained sufficient poise – Chupke Chupke – to have Dharmendra displaying the gumption to compete with Amitabh Bachchan in tones of Sa re ga ma sa re ga ma. This Kishore–Rafi duet materialized, in Chupke Chupke (April 1975), under the baton of the very S. D. Burman in whose Aradhana our giant had been vocally marginalized. Short point – Rafi having been No. 1 for so long, retained the zeal and the zest to find his way back right up there. By contrast, Manna Dey, having never known what it is to be No. 1, seemingly just glossed over what it, in reality, meant to be second to none, once Kishore Kumar Aradhana-happened.

Even before that, Manna Dey had sought my personal advice on the demeaning style of ‘vocal clown’ that he was being turned into as a singer – through his voice being reserved exclusively for Mehmood by even thinking composers like S. D. Burman and Roshan. Manna Dey felt diminished each time someone from his intellectual Bengali community (surrounding his Santa Cruz-located ‘Anandan’ abode) stopped him on his morning walk to ask whether he really needed to continue to sing – on such a compulsively risqué performer as Mehmood – something like Pyaar kee aag mein tanbadan jal gayaa (1964, Ziddi) and Laagee manvaa ke beech kataaree kee maara gayaa brahmachari (1964, Chitralekha). At such times Manna Dey would feel impelled to introspect. He once even asked me if he should refuse to sing for Mehmood since the rendition finally came to sound so double-edged on the screen. I candidly told Manna Dey never to surrender what he had in the basket already, adding that, so long as he was active as a singer, who knew which opportunity would open up when and where?

Such risqué comedy singing was, in truth, tendentious exploitation by composers of the fact that Manna Dey, from the outset, became too set in his classical singing ways to be able to ‘open out’, later, in romantic dueting. Since he was so well groomed (with a knowledge of notation that no other singer in our films had), Manna Dey, later in his career when established, tended to be vocally probing. This some music directors (like Shanker) welcomed, while other composers felt that he should be confining himself to singing, where he still had pronunciation and enunciation problems in the Hindi language. Take C. Ramchandra, who had nothing personal against Manna Dey. While scoring Sharada (December 1957) – with Meena Kumari in the title role – Raj Kapoor made a special plea to have Mukesh’s vocals going on him in the film’s Jap jap jap jap jap re number. C. Ramchandra agreed but added a rider that he would replace Mukesh with Manna Dey, if he felt dissatisfied. Finally, C. Ramchandra let Jap jap jap jap jap re pass in Mukesh’s voice, but brought in Manna Dey for Duniyaa ne toh mujh ko chhod diyaa khoob kiyaa re khoob kiyaa on Raj Kapoor. Yet he was not satisfied with Manna Dey’s wonderful rendition either, arguing that he himself could have put it over better as Chitalkar, under which name, he pointed out, he had sung no fewer than 7 hit numbers picturized on Raj Kapoor, as Rehana’s hero, in Filmistan’s Sargam (1950)! Personally, I found Manna Dey’s rendition of Duniyaa ne toh mujh ko (on Raj in Sharada) flawless.

Could Manna Dey have emerged as the unfading voice of Raj Kapoor?

Maybe! Manna Dey ‘arrived’ as the voice of Raj Kapoor (playing Shree 420 in late 1955) only because Mukesh had unthinkingly contracted himself out (right through the making of his 1953 Mashuqa Suraiya co-starrer). Manna Dey grabbed the Shree 420 opportunity to leave his impress on the silver screen as the neo-voice of Raj Kapoor. If Dil ka haal sune dil waala saw him encapsulate the persona of Raj Kapoor as the Timeless Tramp, screen romanticism itself acquired a showery new dimension, as Manna-Lata dueted for Raj-Nargis in a never-never strain of Pyaar huuaa iqraar huuaa hai pyaar sephir kyun dartaahai dil. Both numbers were the handiwork of Shanker, even if Raj Kapoor himself might have provided the base idea for that dream duet. Shanker tuned Mud-mud ke na dekh, too, for Manna Dey to materialize so cutely on Raj Kapoor. Shanker thus became the composing kingpin on this singer’s singer. The Manna Dey–Raj Kapoor connection, sanctified by Shree 420, was to abide ultra-romantically, as Chori Chori hit the screen just before end-1956. Chori Chori, releasing a full year after Shree 420, is the film with which Manna Dey achieved, on Raj Kapoor, the flexibility of tone that was the scoring point of our Chaplinesque romantic. Those three winsome Chori Chori duets with Lata did put the stamp on Manna Dey as Raj Kapoor’s emerging voice. That Raj Kapoor reverted to Mukesh, even after this ultra-fluid Manna Dey come through, is the rub of the green. A green on which Manna Dey has fielded all composers in all climes at all times. There was (in 1956) no Best Singer Filmfare award on offer when Chori Chori came as a romantic screen event, otherwise Manna Dey perhaps would not have had to wait for a full 15 years (after Chori Chori) before being honoured with the Filmfare Best Singer award for Shanker’s Ye bhai zaraa dekh ke chalo from Mera Naam Joker (1971).

Classically humming, Manna Dey remains unsurpassed. In Lata’s pet Raag Hamsadhvani, how catchily does Manna Dey go along with her in the Salil Chowdhury charmer, Jaa tose naahein boloon Kanhaiya – on Sabita Chatterjee and Ashim Kumar in comedian-director Asit Sen’s Parivar (November 1956) for Bimal Roy Films. No less hoi polloi is Manna Dey, when he is Raag Kedar-dueting with Lata in Chitragupta’s Kaanaa jaa re (from Tel Malish Boot Polish, 1961). If it is in Boot Polish itself (January 1954) that viewers want those Manna Dey vocal gymnastics, they have them in Shanker’s Raag Adana atmosphere builder, coming over, ever so divertingly, as Lapak jhapak tuu aa re badarva (on David, Bhudo Advani & co.).

Can you imagine anyone rendering Laagaa chunaree mein daag in the scale of Raag Bhairavi patented by Manna Dey on Raj Kapoor in Dil Hi To Hai (1963)? ‘After 12 takes going abegging,’Manna Dey told me, ‘I was on the point of exploding, when slave driver-composer Roshan smilingly requested for a baker’s dozen. Magically, that 13th time, my luck held!’By comparison, the no less Raag Bhairavi-laden Phool gendva na maaro (as ‘suggested’on Bharat Bhooshan through Agha in Dooj Ka Chaand, 1964) saw Roshan to be, marginally, less Manna Dey-demanding. If Shanker wanted his Raag Yaman to sound featherweight in Lal Patthar (1971) on Vinod Mehra-Raakhee, there was Manna Dey dulcet-dueting with Asha – Re man sur mein gaa. As for Jaikishan, he crafted his toning of Raag Darbari Kaanada to suit the 1968 Mere Huzoor persona of Raaj Kumar – how Manna Dey’s classical integrity accented the Kaanada ang in Jaikishan’s presentation of Jhanak jhanak toree baaje paayaliya. Madan Mohan tested Manna Dey early, in Raag Rageshri, with that real beauty, Kaun aaya mere man ke duaare, going on Anoop Kumar (playing a singer in Dekh Kabira Roya –February 1957). Madan Mohan, no less vibrantly, employed Raag Rageshri on Rajesh Khanna playing Bawarchi (July 1972)– to find Manna Dey measuring up exemplarily, again, in Tum bin jeevan kaisaa jeevan. S. D. Burman sprang Puchcho naa kaise maine rain beetaayee upon him – says Manna Dey. That this Meri Surat Teri Ankhen 1963 heart-wrencher – filmed on a sympathy-arousing Ashok Kumar in quintessential Raag Ahir Bhairav – came to be rehearsed overnight (with Dada Burman reaching Manna Dey’s ‘Anandan’home in a banyan!) is a telling testimony to our singing titan’s taiyaaree (readiness to absorb).

Yet, imagine, this in itself became a mental block to Manna Dey’s advance. He knew too much for our topmost composers. By the same classical token, he gave a near inferiority complex to our later line of music makers. Either way, Manna Dey was the one to lose out. Has he any regrets? None whatsoever. Today – as he did when still active as a singer – Manna Dey accepts life as it comes, even growing indulgent about the views he holds on competitors. If you think Manna Dey to be well versed, you should be interacting with his wife, the soft-spoken Sulochana from Kerala. Any conversation with Sulochana– as with Manna – is an experience in shared ideas. The pair, Manna and Sulochana, represent a fount of musical knowledge.

Today, at 91-plus, Manna Dey has nothing more to prove. In the 68 years during which he has enriched our musical vocabulary, Manna Dey has left his imprimatur on the Indian psyche with the sustained resonance of his performance. He is not a miser hoarding songs, but a millionaire expending them on the audience. Manna Dey, as the Great Caruso of Hindustani film music, never ceased to amaze me with his vocal resilience of mind and spirit. With his sheer elasticity of throat, even while performing in the heat and dust of competitive advancement.

The 2005 Padma Bhushan came as a timely tribute to his style and technique at a stage in his life when he felt he had seen it all, experienced it all. News of his being bestowed with the 2007 Dadasaheb Phalke Award for Lifetime Achievement arrived at a late-2009 point when he could have been philosophically wondering if he had not wasted his life. An experience it still is listening to Manna Dey, as he puts over, with empathy on the stage, such non-movie evergreens as Naach re mayuraa and Nathnee se chhoota motee re. A singer for all ages, Our Man Manna. Even if, in revealing the humility he does in his Autobiography, he tends to falter in esteeming his own true worth. A mindscape best epitomized in the 1956 Shailendra–Shanker Basant Bahaar mould of:

Sur na saje kyaa gaaon main

Sur ke bina jeevan soonaa …

Sangeet man ko pankh lagaaye

Geeton se rimjhim ras barsaaye

Svar kee sadhna svar kee sadhna

Parmeshvar kee …