So long did the ‘Big B’ get to rule as the king-emperor of violence that his near 25-year span (1973–97) progressively reduced music in our cinema to an exercise in din making at various pitches. A further low did Amitabh touch, for someone of his background, with his 1981 enaction of Mere angane mein tumhaara kyaa kaam hai in Prakash Mehra’s Lawaaris. Megastars have necessarily, at some stage in their careers, to rethink the immense sway they hold over the audience by way of a broader national commitment.

When and where did Hindustani cinesangeet’s deplorable degeneration into sheer ‘tin-boxing’ really begin? Undoubtedly in January 1975, when the dubious Mozart ‘art of making music throatily and palpitatingly sexual’ passed, irrevocably, into the fists of the fight composer from the baton of the song composer. Remember Yash Chopra’s January 1975 Amitabh Bachchan– Parveen Babi–Shashi Kapoor–Neetu Singh starrer Deewaar? Well, its long-playing record (POLYDOR 2392060) told it all. In bold print, it announced on its cover:

POWER-PACKED DIALOGUES

along with 5 Original Songs

How did the Salim-Javed dialogues (sic) come first, the R. D. Burman songs after? See how dismissively did the Deewaar LP – projecting the Big B’s picture with that Bombay Dock 786 Mogal Line seal embossed on top of his arm– push R. D. Burman’s ‘5 Original Songs’ to the right hand nook – below Salim-Javed’s POWER-PACKED DIALOGUES! Even those ‘5 Original Songs’, I recall, meant only the 5 song originals as figuring in the film and as reproduced on the LP – no way did they signify any originality of composition displayed in music making by R. D. Burman.

Any wonder that, a full 4 years before Deewaar unfolded, Salim-Javed’s career-building claim had carried total conviction, as this deadly duo submitted that they, not Shanker-Jaikishan, were the real SJ! Salim-Javed’s prime function, as ‘the real SJ’, was to ensure that the decibel level, in an Amitabh Bachchan film, rose in direct proportion to the number of songs, in it, getting shot down to 5 with Deewaar – ‘progressively’ to 3 in such a genre of film. That such a gut switch (from song to dialogue) should have originated with a film done by so famed a musical romantic as Yash Chopra is the grim irony of it all.

‘I would always give a Salim-Javed script the highest priority,’ Amitabh had told me then. How woefully the Big B got his screen priorities wrong came to be driven home with a vengeance as his reign extended from Zanjeer (1973) to Mrityudaata (1997) – a near quarter century during which the fight composer called the ‘tinpot’ tune from the first shot to the last. To think that the first half of Bachchan reads Bach! If you, therefore, asked me to underpin the one solid reason for the decadent decline of Hindustani cinesangeet, I would say it is Amitabh Bachchan. As a hero beyond all-time compare – as a hero who, while many rose and many shrank, grew to be the tallest perpendicular pronoun in Hindustani cinema – the Big B, regrettable to say, betrayed a sad lack of social conscience in the thoughtless idolizing of violence that he speciously spawned on the eversilver screen.

The spoken word’s preceding the 5 songs, on the Deewaar LP, signalled a process by which that biggie movie had Amitabh raising himself to his full stature with his superstar-crossed back to the wall – positioned in a form and format frightening enough to confirm this megastar as the genie never again to be put into the bottle. Some may project, by way of defence, his softer Kabhi Kabhie (1976) contours in between. But one Kabhi Kabhie-swallow could not our musical summer make. More films by our cult hero in the 1976–77 Kabhi Kabhie-Alaap denomination could, perhaps, have softened the after-effect of the knockout punch landed on Hindustani cinesangeet by Amitabh with his Mogal Line ‘left’.

The phenomenal multistardom-conferring rise of Manmohan Desai in a mere 6-month span during the post-Emergency era (between 1 April and 28 October 1977) –with Amar Akbar Anthony and Parwarish in the multistarrific wake of Dharam Veer and Chacha Bhatija – further affirmed dishum-dishum as the timebomb-set sound of music in our cinema. This was the fatal phase in which the Big B set the ‘fight composer’ tone in emerging as a larger-than-LIFE magazine influence on the swadeshi screen, having added immeasurably, if dubiously, to his media aura by Bollywood-peckingly cozying up to Rekha (following their groovy togetherness in Do Anjane-Khoon Pasina, 1976–77) – a relationship winning the two a calibre of catchpenny popularity best described as tawdry. All this from a ‘sophisticasted’ public-schooled elitist personality with a formidable literary background – a background suggesting an instinctive commitment to the fine arts rather than to crass commerce. In so dragging down cinematic standards, Amitabh, given the punch he packed in ‘A Fistful of Dollars’, dealt a body-blow to vintage music and its ‘art history’ in our cinema. Manmohan Desai’s Amar Akbar Anthony (Amitabh Bachchan-Parveen Babi, Vinod Khanna-Shabana Azmi, Rishi Kapoor-Neetu Singh); Parwarish (Amitabh Bachchan-Neetu Singh, Vinod Khanna-Shabana Azmi, Shammi Kapoor-Indrani Mukherjee); Dharam Veer (Dharmendra-Zeenat Aman, Jeetendra-Neetu Singh), Chacha Bhatija (Dharmendra-Hema Malini, Randhir Kapoor-Yogeeta Bali) – those four blockbuster movies, coming almost cheek by jowl in a six-month clutch – saw Laxmikant-Pyarelal (as music directors of ‘the quartet’) leaving R. D. Burman far behind for Bappi Lahiri to close in for the cacophonous kill. Never from this point did the Laxmikant-Pyarelal duo surrender their dubious dominance of our music scene, their growing market value seeing them doing a record 502 films in 35 years at the harmonium. Lyricist Anand Bakshi joined the duo in churning out the class of Manmohan Desai poetry that turned song-lyrics into sheer abracadabra.

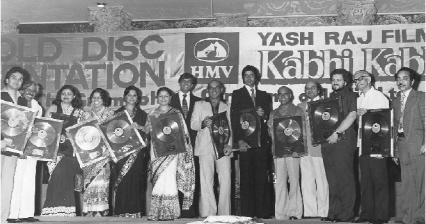

A silver jubilee to remember: HMV presented gold discs to producer-

director Yash Chopra, music director Khayyamand other toppers for sales

achieved by songs of the 1976 path breaker: Kabhi Kabhie. At an earlier

such function, Mukesh had insisted we listen to him only after

Amitabh – to gauge the contrast

On the sets of Mard (1985) Manmohan Desai became so colourful in the language he employed that the Big B had politely to counsel restraint. ‘Even you can’t halt me here, Amit, when all I’m doing is speaking in my matrubhasha!’ (mother tongue) came back ‘Man’. While urging such ‘Man’ tonedown, the Big B – as the Mard Tangewala presuming to tame the mock-propositioning Amrita Singh playing Ruby – proceeded to affront cinema itself by addressing his mesmerized audience direct in seeking their approval of what to do with the lady urging him to spot-perform. If that was not the height of cinematic irresponsibility, what is? So long did ‘The Big B’ get to rule, as the king emperor of violence, that his extended span, progressively, reduced music in our cinema to an exercise in din making at various pitches. A further low did Amitabh touch, for someone of his background, with his 1981 enaction of Mere angane mein tumhaara kyaa kaam hai in Prakash Mehra’s Lawaaris. Megastars have necessarily, at some stage in their careers, to rethink the immense sway they hold over the audience by way of a broader national commitment.

Dismayingly, there was no such conscious attempt by Amitabh to reflect upon venturing to reverse the vicariously vicious trend he had superciliously set in motion with Zanjeer (1973). Once Alaap (a film based on classical music in which Jaidev was the composer) came unstuck at the box office, that 1977 year witnessed the Big B’s becoming a near robot in Manmohan Desai’s ‘megaphoney’ hands. So much so that even Yash Chopra’s Silsila looked a calculated 1981 move towards ‘filmizing’ his abiding Rekha connection! No wonder many argue that, while Rajesh Khanna as a superstar helped set a new musical mode in healthy collaboration with R. D. Burman, Amitabh Bachchan was content to ride the rollercoaster that took him, razzledazzlingly, to a neo giant-wheeling high. Grappling with ‘The Big-Bad-B to Be or Not to Be?’ syndrome thus became a dilemma in itself – a dilemma witnessing Amitabh rising like a behemoth – only to discover that there was no visible return to screen sanity.

There was, given such a setting, hardly any attempt by Amitabh – as the face of our cinema became more and more malevolent in his talismanic custody – to explore the softer hues of this commercio-art form. Even in the hands of Hrishikesh Mukherjee, both Namak Haram (1973) and Mili (1975) merely saw Amitabh – well as he acted in both films – further burnish his Angry Young Man image. Is it a mere coincidence that Amitabh’s one-man rise – by which even the heroine became a mere Parveen Babi style of eye-candyfloss appendage in our cinema – coincided with the copy-catty advance of Bappi Lahiri as a music maker raucously rivalling R. D. Burman, while Laxmikant-Pyarelal meretriciously moved far ahead in the field? Bappi Lahiri, like a bull in a china shop, fatally changed the very tone of tune making in Hindustani cinema. Today, I challenge you to reel off 10 tunes by which we could ‘place’ the role of such music makers as Bappi Lahiri and Anu Malik in Hindustani cinema. Do you heart-touchingly remember even one song by any of them? Under their baneful baton, verily did music become mercenary merchandise in our cinema.

I recall being ushered into R. D. Burman’s Santa Cruz North Avenue ‘Marylands’ music room, on the Saturday of 22 October 1983. As I waited for Pancham to arrive, I sized up that high-ceiling music room where some of our finest tunes in 20 years had taken shape. The twin air-conditioner exuding a nice breeze I took as a pointer to Pancham’s needing to keep his cool at a crisis point in his career. The music room was spacious enough to fit in an orchestra of 25 performers at one rehearsal go. I saw two harmoniums bearing the stamp of ‘US Ramsingh & Bros’. I counted no fewer than 21 bolsters on view in a music room looking spotlessly white. There was, lying on the main gaddee, a State Express 555 cigarette packet, something Pancham had been advised to avoid. It was a music sanctum to remember as RD entered in a lungi. Ultra-polite as always, almost embarrassingly deferential while addressing me as ‘Raju Saab’, here was the musician’s musician in front of me – if I was to give the trackblazer his true due. Our tuneful interaction had just begun when in walked Majrooh Sultanpuri with his latest song-lyric for Nasir Husain’s Manzil Manzil (due in 1984 and starring Dimple Kapadia, Sunny Deol and Asha Parekh). ‘Sorry about penning something that is an apology for poetry and daring to put it in front of Pancham when a critic of your level is present!’ Majrooh excused himself. ‘But this is cinema, Majrooh Saab,’ I responded, somewhat discomfited by such a mature poet’s submissive stance. ‘Here you have to go along with the market forces.’ Majrooh’s response: ‘No, Raju Saab, I offer no such justification for what I’m penning. In fact I’m quite ashamed of what I’ve just written. But this is what Pancham wants and I, as a professional, give it.’

‘No, Majrooh Saab, don’t pass on the blame to me!’ pleaded Pancham instantly. ‘It’s what Nasir Husain wants and you and I have simply to carry out his wishes.’ The same Majrooh Sultanpuri, I recall, had told me once: ‘Sorry to say this, but the son does not understand poetry at all.’ To which I had got back with: ‘Put that way, Majrooh Saab, even the father [S. D. Burman] did not understand Urdu poetry.’ Thereupon Majrooh’s retort was telling: ‘The father might not have comprehended Urdu fully but he still understood poetry, which is the same in any language. I’m here talking of the feel for poetry, which SD had, RD doesn’t have.’ May be Majrooh had a point there, may be he did not. We only know that the music Pancham made with Gulzar – even the work he did with Javed Akhtar in Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s 1942: A Love Story – was creative in the true sense of the word. But yes, as Pancham’s grip began to weaken, in stepped Bappi Lahiri to turn RD’s Asha Bhosle into the singer of the highest number of film numbers (over 12,500) by any performer in Hindustani cinema. Numbers – that is all Bappi Lahiri gave Asha Bhosle and Kishore Kumar (with a career total of 2845 songs in films). I do not therefore think that Majrooh was being totally fair to RD, recalling the musical sensitivity and refinement Pancham showed each time he worked with an introspecting (song) writer-director like Gulzar.

Even Gulzar, for his forward-looking part, had indirectly hinted at having problems tuning with Madan Mohan in Mausam (January 1976). ‘I did only one film with him!’ Gulzar told me, obviously discounting his 1972 Koshish (Jaya Bhaduri-Sanjeev Kumar) in which the two Madan Mohan songs (SP No. BOE 2750) were purely atmospheric. Gulzar the creative maker perhaps sensed Madan Mohan the inventive composer as being at home only with the court style of Urdu poetry being written in films through the ages. Gulzar, by contrast, sought to bring into youthful fashion a more modern norm of Urdu poetry. But Madan Mohan was clearly having none of it. Following Mausam (1976), Gulzar was all set to direct Premji’s Meera (to come in May 1979) when Messrs. Laxmikant-Pyarelal walked out of the film, shrewdly sensing that Lata, near obsessively, wanted her brother Hridaynath Mangeshkar to compose the Meera theme. LP’s alibi for backing out was classic – the duo argued that ace composer Roshan had already raised Meera via Lata to such a high with Aeree main toh prem deewaanee (on Nalini Jaywant in Naubahar, 1952) that they did not think they could compose anything to excel such a Raag Bhimpalasi classic! I remember asking Gulzar, at the time, if he had ever considered Raag Bhairavi specialist Naushad as ideally equipped to score the Meera theme. ‘Forget a traditional theme like Meera,’ came back Gulzar, ‘my style of poetry, do note, just doesn’t blend with Naushad Saab’s idea of music. Naushad Saab is a stickler for old world Urdu, something I am trying to change as not in tune with modern-day cinema.’ Yet it was such flowery Urdu poetry, so easy on the ear, that had scrupulously upheld standards of music in Hindustani cinema.

In fact, it was because poetry came first, the tune after, that Madan Mohan, as I view it, failed to win unfailing instant assent as a ‘popular’ music maker in his later years. His insistence upon high-octane Urdu content elevated him into the more literary bracket. In Madan Mohan’s Rajendra Krishna-penned Adalat (1958), one went from ‘verse to tune’ – a fatal failing in a composer seeking spot public approval. If only because the public in India, that way, does not readily understand Urdu poetry. But if ‘tune leads to verse’, even such a neo-literate listener begins at least to try and grasp the finer tones of the poetry going with the song.

Was not the poetry in Naushad’s music equally literary in form and content? How then did Naushad’s tunes win ready popularity with quality Urdu poetry? I would flesh this out as Naushad’s very special musical gift. Naushad was choosy enough to pick out, fairly early in his career – for those 10 songs in A. R. Kardar’s Suraiya–Nusrat–Munawar Sultana starrer Dard (1947)– Shakeel Badayuni as his personal poetic preference. Naushad, as one himself into verse, needed an Urdu poet who would write the song the precise way he wanted it done, so that his tune and Shakeel’s wording would even out in the public ear. It is Naushad’s exemplary contribution to Hindustaniat in film music that he maintained his hold on the public imagination without ever letting the standard of poetry in his composition drop. Take any Naushad tune from Mohammad Rafi’s Raag Pahadi Tasveer banaata hoon teree khoon-e-jigar se (on Suresh in A. R. Kardar’s Diwana, 1952) to Lata Mangeshkar’s Raag Bhairavi Mere paas aao nazar toh milaao (on Vyjayanthimala, 16 years later, in H. S. Rawail’s Sunghursh), you will find that it is the Naushad tune that dovetails into the Shakeel verse. I am not suggesting that it is the calibre of poetry in his films that was Madan Mohan’s undoing at the turnstiles. Such obtuse thinking would be to query the very rationale of Madan Mohan’s noblesse-oblige music. In the case of the no less sahitya minded Roshan, somewhere down the line – after early box-office halts alongside Madan Mohan – this composer too began picking up the Naushad knack of garbing the Sahir scale of poetry in the style of tune that found wider public acceptance – in the combo’s Barsaat Ki Raat-Taj Mahal 1960–63 span. This, mind you, is the very era in which Madan Mohan, as Ghazalon Ka Badshah, grew in musically poetic stature.

In poetic stature, yes, but not always in musical popularity. Any composer has to pass the litmus layman-equating test. In the East as in the South of India, for instance, knowledge of Hindi-Urdu’s subtler points might not be great. But a certain awareness of poetry is obviously there. Madan Mohan loved football as much as he did cricket. Yet not always, in his later music, did he keep the demands of the grass-roots football fan in mind. His later music lacked kick while unfailingly exuding class. It had rare poetic quality beyond doubt. But in a field where you are judged in the marketplace, you have to be able to emulate a Naushad to so marry music and poetry as to find acceptance with Mr Everyman too.

Madan Mohan certainly displayed this gift early on without totally shedding class – the art of reaching out to the aam aadmee (common man) with his music. But, as he won higher and higher Lata Mangeshkar-performing favour, he began to compose for the courtly, all but ignoring the courtling. For example, while setting up music for 1955 Railway Platform display, Madan Mohan had this aptitude to get Mohammed Rafi’s Bastee-bastee parbat-parbat accepted, by the everyday audience, alongside Lata’s Chaand madhdham hai as an all-time classic. Somewhere along the Railway Platform line, he lost this dual knack. The populist muse deserted him as, ironically, he added square inches to his standing as a drawing-room composer. Madan Mohan became an artistic misfit as the bedroom composers took over the craft of tuning. As the Zeenie Baby mould of ‘Max-Factory’ leading lady cut into good old Urdu-Begum territory, thereby enunciating a mod maxim of ‘New Vamps for Old’, Madan Mohan with his ghazal base was at a loss to know how to impose rather than compose. Think of the entire conspectus of Hindustani film music and one would find that it is less Hindi sahitya and more Urdu shaairi that invests our song lexicon with the priceless collector value that tunes started acquiring from 1947 onwards – with Lata’s sensational advent.

By contrast, post-1975 is the time witnessing Hindustani film music hitting the pit. After a near 20 years of mindless screen violence following that, halfway into 1994, small-timer Raam-Laxman showed promise by becoming a tuneful part of a healthy new musical trend set by Sooraj Barjatya with Hum Aapke Hain Koun. The film and its smash hit music took the nation by agreeable surprise. After that, Raam-Laxman went on to do a rash of films but soon got lost in the maze of Bollywood – as did over half a dozen duos emerging on the screen after Shanker-Jaikishan. Can anyone today recall Sapan-Jagmohan and Bipin-Babul? Or a single song from their repertoires? Whatever happened to Anand-Milind and Jatin-Lalit after the trendily tuneful start they took? Both Anand-Milind (the phenomenally resourceful Chitragupta’s sons) and Jatin-Lalit (the Pandit Jasraj lineage underscored by the vocals of sister Sulakshana Pandit) strike you, in retrospect, as truly inexplicable fadeouts. Nadeem (of the Nadeem–Shravan team) was just beginning to sound a fair tuning talent, when he got into a tangle that negated the duo’s entire body of work. The latter-day duos did have something. Yet they were not able to display the staying power needed to graduate as true-blue composing steed in commercial cinema.

Why? Because music grew audibly ‘tacky’ during the Anand–Milind and Jatin–Lalit era of the Gulshan Kumar–Anuradha Paudwal takeover. Even today, as you go to Vaishnodevi or on Amarnath Yatra, you admittedly hear only Gulshan Kumar’s T-Series music with Anuradha Paudwal for its bhajan punchline, coupled with some other prominent names like Narendra Chanchal and Anup Jalota. What did even Anuradha Paudwal really establish after daring to confront the Mangeshkars headon? Nothing tangible in the grand sum, for Anuradha Paudwal herself became the driving force behind a corpus of humdrum music which did little to improve standards – at least in films.

Could path-pointers Laxmikant-Pyarelal and R. D. Burman have done more to improve the tone of Hindustani film music? They could have but they compromised to a point where the trend set the pace, for them, rather than their setting the trend. The problem of musical standards plummeting in our cinema began as the cartel of Shanker-Jaikishan, Kalyanji-Anandji, Laxmikant-Pyarelal and Ravi took the initiative in booking each and every recording studio (barring Mehboob Studios refusing to oblige) in the city of Bombay and beyond – from 1 January to 31 December – for the entire year. In this grimly forbidding setting, if a Madan Mohan, or a Khayyam, or a Jaidev wanted to ‘take’ a song, such an infrequently recording composer had to ring one of the ‘above four’ to spare the music studio for that day. The permission thus sought was instantly granted, but just imagine the creative humiliation of these ‘greats’ at having to seek such permission. Where it had been a singing monopoly of the Corsican Sisters before, it was a ‘Cartel of Four’ music directors calling the recording room tune. Madan Mohan died a totally frustrated man in the circumstances. Neither Khayyam nor Jaidev, even less Salil Chowdhury, had the commercial clout to change the music recording order. They sheepishly fell into line with the system, for creativity to become the first casualty in Hindustani film music. There were no true trends and, therefore, nothing genuine to follow.

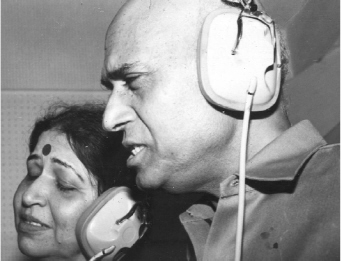

Jagjit Kaur-Khayyam: tonal testimony to

what team work can achieve

Well may you ask: ‘Was no good music then made in this 1987–96 era?’ It was and it wasn’t. It was in the sense that Laxmikant-Pyarelal, alongside R. D. Burman and Rajesh Roshan, did compose meaningfully at times. But since they faced no real challenge, there was no true spur to being innovative, unlike their predecessors being called upon to prove their mettle in competition with 10 other music directors, equally inventive at the same time. Moreover, this is when even Radio Ceylon, as it turned into Radio Sri Lanka, became the citadel of corruption. The entire 8.00–9.00 a.m. farmaishi one-hour programme was ‘bought’ through its first 20 minutes of play. It was an organized racket and, like all such quick-fix deals, it was run with clinical professionalism. Over the years, the programme lost total credibility. It was amazing how much without scruple our Trio of Duos grew in their pursuit of pelf. Admittedly, even Ameen Sayani’s Binaca Geetmala was not totally free from such attempts by music makers to influence its paaidaan course, especially in its latter more vulnerable stages. Binaca Geetmala’s transformation into Cibaca Geetmala was but symptomatic of the fast-sinking standards, a downslide by which what we, growingly, got to hear was sheer tinsel in tinpan alley. An occasional number did catch one’s ear but, on the whole, this was clearly ‘tinny’ music studiedly being made not to last.

R. D. Burman, for his placid part, never could come to terms with the every-other-Friday fear of the box office, the way Laxmikant-Pyarelal could from their salad days. LP, like Shanker-Jaikishen, specialized in capturing ‘camps’. How crucial a component did Messrs Laxmikant-Pyarelal thus go on to become in Subhash Ghai’s emergence as a biggie maker with a rare ear for popular music? Parasmani was all set to go solo to Babul (of the defunct Bipin-Babul team) when Laxmikant-Pyarelal cut in, as debutants, to turn the film into their (1963) ‘musical arrival’ on the Hindustani film scene. Likewise, Subhash Ghai shot through only after, as an assistant, he ambitiously supplanted seasoned director Dulal Guha in the controversial trail left by Khan Dost (1976). As this blockbuster damp-squibbed and Subhash Ghai, as its directorial assistant, offered to try and retrieve lost Shatrughan Sinha ground, he went on to make his name– as one ‘transistorly’ hooked on cricket –with Kalicharan (1976) and Vishwanath (1978). If thus far he was with Kalyanji-Anandji and Rajesh Roshan, Subhash Ghai showed his musical paces as he tuned with the more talented, better grass-rooted Laxmikant-Pyarelal in Gautam Govinda (1979). SG-LP – in conjuring tunes at once ‘on’ and ‘in’ – came to status-symbolize one of those durably rewarding musical combines. SG-LP had a mutual role in each aiding the other in rising to a fresh career peak. In fact, so long as LP were with Subhash Ghai, they even took note of musical swings – starting with Karz (1980). Not until (the wives of) Laxmikant and Pyarelal uglily fell out (during a concert tour abroad) did Subhash Ghai – as the spectacular Raj Kapoor calibre of showman — need to think in terms of a switch to Nadeem-Shravan with Pardes (1997). From there, near inevitably, to A. R. Rahman with Taal (1999).

For sheer tunefully thematic variety in the showbiz technique of truly mind-sweeping widescreen presentation, Subhash Ghai must rate as one of the big musical guns of Hindustani cinema. Not once did he need to turn to the Big Bmental crutch. In fact, Subhash Ghai’s Dilip Kumar–Raaj Kumar casting coup in Saudagar (1991) remains a pointer to this maverick maker’s flexibility of mind and spirit. If for nothing else, I will remember the SG–LP teaming for Lata Mangeshkar–Madhuri Dixit’s heart-touching O Ramji badaa dukh deenaa tere Lakhan ne in Ram Lakhan, the 1989 show affirming Anil Kapoor and Jackie Shroff as finding their true histrionic feet. That Subhash Ghai, too, ultimately lost musical ground is the mood of the moment. Before that, in staying the songful course through a near quarter century, he was a subject lesson in thematic pacekeeping to Laxmikant-Pyarelal – themselves an object lesson, in professionally delivering, to Subhash Ghai.

If Subhash Ghai explored newer and newer vistas in music via Laxmikant-Pyarelal at the height of the dishum-dishum Big B era, a similar hybrid invasion of our tinpan alley there had been, in the latter half of the 1950s, by O. P. Nayyar – when composing standards, otherwise, were quite high. It was such an obstreperous entry by Nayyar that had prompted Shanker (of the Shanker-Jaikishan team) – with the aid of Shailendra – to deride OP as a parvenu by charging, Idhar se le kar udhar jamaa kar kab tak kaam chalaaoge? A rhetorical query considering SJ themselves – as a duo no one accused of originality by then – were notoriously guilty of the same lift-and-sift crime by that 1959 stage. A stage seeing the duo employing the vocals of Mohammed Rafi on Dev Anand – for the first time – in Love Marriage (opposite Mala Sinha). Talk of the ‘tinpot’ calling the ‘kettledrum’ black – as, here, you have Shanker mocking Nayyar via OP’s own Rafi as:

Teen kanastar peet-peet kar

Galaa phaad kar chillaana

Yaar mere mat buraa maan

Yeh gaana hai na bajaana hai

Teen kanastar…