The one-and-only Yash Chopra, after 50 years into films, remains the ultimate romantic in Hindustani cinema – some feat as far as the mortality rate in this mindlessly mercurial industry goes.

Many of you will be surprised to learn that India’s singing legend Lata Mangeshkar did not record a single song for a Yash Chopra-directed film through 13 years, following the 1959 Sahir-penned solo in Dhool Ka Phool – Tuu mere pyaar ka phool hai ke meree bhool hai kuchch keh nahein saktee/Par kisee ka kiyaa tuu bharein yeh seh nahein saktee. In fact, after this Lata solo witnessing Yash winning his directorial spurs, it was Asha Bhosle all the B. R. Films way through Dharmputra (1961), Gumrah (1963), Waqt (1965), Hamraaz (1967), Aadmi Aur Insaan (1969) and Dastaan (1972). ‘Lata, even today, is not welcome at B. R. Films,’ Baldev Raj Chopra told me as I met up with him after the banner disaster that was Dastaan, released on 3 March 1972 and teaming Sharmila Tagore with Dilip Kumar for the first time. True, after Dastaan, B. R. Chopra and Lata Mangeshkar did make up, as the two became key negotiators in resolving the 4-month-long musicians’ strike that hit the Bombay film industry in 1974. But by then much had changed. The younger Chopra had stepped out of the BR wings to set up his own Yash Raj Films with the launch of Daag (the Sharmila Tagore– Rajesh Khanna– Raakhee biggie arriving in April 1973). In thus making a fresh career start, Yash (via wife Pamela) had retuned unhesitatingly with Lata for the Ab chaahe maa roothe yaa baaba yaara maine toh haan kar lee Kishore-accompanied duet (on Sharmila-Rajesh). It was a duet written by B. R. Films resident poet Sahir Ludhianvi who had remained exemplarily neutral in the Chopras’ face off and continued to write, at nothing but his best, for both brothers. In fact, it was only in early-1976 that Sahir ceased writing for the elder brother as the Basu Chatterjee-directed Chhoti Si Baat title song got to be penned by Yogesh. This, in fact, was when –in the afterwave of their reunion during the musicians’ strike –B. R. Chopra condescended to bring back Lata, after a 16-year gap, to record the Salil Chowdhury-tuned Na jaane kyun hotaa hai yeh zindagee ke saath, voiced over on Vidya Sinha (vis-à-vis Amol Palekar).

The long-running Lata–B. R. Chopra feud had nothing to do with our diva’s insisting upon song royalty but with the controlled recording fee that the Chopra patriarch insisted upon paying under his banner. A fee that, at least partly, accounted for Mahendra Kapoor’s holding firm under the B. R. umbrella – as No. 1 male singing choice –through 10 years (1959, Dhool Ka Phool, to 1969, Aadmi Aur Insaan) when pitted against someone so vocally charismatic as Mohammed Rafi. Actually, in the thematically engrossing Dhool Ka Phool, it was Rafi who had symbolized (in Sahir song) the film’s strong secular content, cutting across the Hindu–Muslim divide, via Tuu Hindu banegaa na Mussalman banegaa (as tuned in Raag Bhairavi by N. Dutta to go on Manmohan Krishna). Both Dhool Ka Phool (1959) and Dharmputra (1961) –the latter rating as a landmark in probing the mindset that stirs the communal cauldron–had marked out Yash Chopra as a director acquiring a strong story-sense base before beginning to experiment as a romantic. How the two brothers differed in their approaches to marrying music to the theme! BR, story-aligned at all times. Yash, more tunefully venturesome from 1965 Waqt down.

The 1961 music made in the Yash Chopra-directed Dharmputra by N. Dutta went so expressively with Sahir’s poetry that one wondered why it turned out to be that composer’s sayonara under the B. R. Films’ banner. True, as conceded by BR himself, Dharmputra (after winning wide critical notice) finished as a total disaster at the cash counter. But it saw fresher Mahendra Kapoor scoring tellingly–under Yash via Sahir – with Aaj kee raat nahein shikwe shikayat ke liye (voiced over on Rehman during that wedding night scene with Mala Sinha); Bhool saktaa hai bhalaa kaun yeh pyaaree aankhen (Shashi Kapoor–as a newcomer still– wooing Indrani Mukherjee); taken side by side with the purely atmospheric Yeh kis ka lahoon hai kaun maraa and Jay jananee jay Bharat Maa. Not to miss out on the same Mahendra Kapoor’s Yeh masjid hai woh butkhaana (with Balbir & Chorus) in the same Dharmputra. Thus the process of its being Mahendra Kapoor, all the way, at B. R. Films had already begun by 1961, which had a momentary halt as Laxmikant-Pyarelal displaced Ravi in the B. R. dispensation with Dastaan (1972) for Rafi to take over, impressively, with Sahir’s Na tuu zameen ke liye hai na aasmaan ke liye–to be voiced over on Dilip Kumar. But even in that 1951 Afsana remake by B. R. Chopra, Mahendra Kapoor was still fairly prominent –with O melaa o melaa jag waala saathee mere chaltaa rahe and Maria my sweetheart (duet with Asha). So who shall say that the much lesser-than-Rafi fee, for which Mahendra Kapoor settled at B. R. Films, had this singer (given his vocal range) performing at anything below his resonant best for that banner –via, for instance, Sahir–Ravi’s Dil kartaa o yaara dildaara (with Balbir, Joginder & co.), going on those army jawans in Yash Chopra’s Aadmi Aur Insaan (1969).

Alongside Mahendra Kapoor’s advance, it is pertinent to view the way Asha Bhosle (when still lagging behind Lata) delivered, at B. R. Films, during the crucial years her elder sister was compulsively away from that arena. Asha took off with the 1961 N. Dutta-tuned Dharmputra solo going as Main jab bhee akelee hotee hoon tum chupke se aa jaate ho (on Mala Sinha eulogizing the still personable-looking Rehman); following up with Kyaa dekhaa nainon waalee nainaa kyun bhar aaye on the same actress. Later, as Asha’s pet composer Ravi ascended the B. R. Films platform with Gumrah (1963), she got to put over, on Mala Sinha again, the two-part Ek thhee ladkee meree sahelee saath palee aur saath hee khelee (though why no 78-rpm disc was issued of this solo is a mystery). Plus Gumrah had that ever popular Asha–Mahendra Kapoor-rendered, Sahir written duet going on Mala Sinha-Sunil Dutt as Ein hawaaon mein ein fizzaaon mein. Not to speak of Asha’s Murgaa boley kukadoon koon (duet with Usha Mangeshkar)– picturized again on Mala Sinha and two kids.

It was with Yash Chopra’s first blockbuster Waqt (starring Sadhana, Sunil Dutt, Raaj Kumar, Sharmila Tagore, Shashi Kapoor and Balraj Sahni) that Asha really came into her vocal own, as Yash got to imaginative grips with the concept of song picturization by 1965. Each one of those six Sahir-written and Ravi-tuned Waqt numbers is a real ear-catcher: Kaunaaya ki nigaahon mein chamak jaag uthee(on Sadhana); Chehre pe khushee chhaa jaatee hai (on Sadhana at the piano as Sunil Dutt and Raaj Kumar watch); and Aage bhee jaane na tuu peechche bhee jaane na tuu (surprisingly picturized on an obscure-looking nightclub performer–after being so suggestively worded –as Shashikala and Raaj Kumar are spotted to be ballroom dancing). Plus there are those three Waqt-tested Asha duets with Mahendra Kapoor: Hum jab simat ke aap kee baahon mein aa gaye (Sadhana in Sunil Dutt’s capacious arms); Din hai bahaar ke tere mere iqraar ke (Sharmila Tagore and Shashi Kapoor on a floating platform); and Maine dekhaa hai ke phoolon se ladee shaakhon mein (Sunil Dutt and Sadhana romancing). Each number is compellingly composed by Ravi and piquantly picturized by Yash. The younger brother, as an emerging romantic, thus remained ahead of his mentor, in this specialist song-taking department, from the day he picked up the megaphone at B. R. Films. No wonder the one-and-only Yash Chopra, after 50 years into cinema, remains the ultimate romantic–some feat as far as the mortality rate in this mindlessly mercurial industry goes.

Moving away from the iconic B. R. Chopra with Daag (April 1973), scaling fresh musical highs all along the Sahirized poetic line, Yash Chopra has sustained, not just his YRF banner’s validity, but also its brand vitality, through as many as 40 productions including son Aditya Chopra’s 1995 pathbreaking grosser of grossers Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge. Yash himself has directed 16 plus 5 films –if you reckon with the quality of the quintet he shaped in the 1959–69 span (Dhool Ka Phool, Dharmputra, Waqt, Aadmi Aur Insaan and Ittefaq) while finding his cinematic feet at B. R. Films. Today Yash might have ceased directing films himself after Veer-Zaara (2004) but, who knows, there is always a last call of the megaphone to be heeded, once you get the feel of wielding it as resourcefully as this Mohican has done. There is, for Yash in this direction, the 1927–84 (Netaji Palkar to Jhanjhaar) example of V. Shantaram, who demonstrated that the job knows no 50-age bar!

The 2004 Veera-Zaara saga of being ‘Lata Mangeshkar vis-à-vis Madan Mohan’ is the 2010 Veer-Zaara aura of being ‘Lata Mangeshkar vis-à-vis Yash Chopra’. That is how instinctive (in the case of Lata-Yash) the Pam Choprapport of musical ideas is, in the public eye and mind, over the last 35 years. Starting with the 1975 launching of the Sahir-written, Khayyam-tuned Kabhi Kabhie, the poem in celluloid triangularizing –with a certain romantic flair –that Shashi Kapoor– Raakhee Gulzar–Amitabh Bachchan casting coup brought off by Yash. A coup turning Kabhi Kabhie into the cult movie of a whole generation. ‘Life is Love and Love is Life’ was Yash Chopra’s Kabhi Kabhie punchline. It was via the Lata–Sahir combine that this BR rebel cut through, as a dramatic music-oriented romantic, with Jab bhee jee chaahein nayee duniyaa basaa lete hain log/Ek chehre pe kaiiee chehre lagaa lete hain log– the Lata solo so cuttingly picturized on Sharmila vis-à-vis a Rajesh falling for Raakhee –at her expense. A 1973 Raakhee–Rajesh–Sharmila song connection bringing home via Daag, Sahir stingingly, the Rajesh Khanna– Anju Mahendru break-up–its after-imagery still so graphic in the Daagviewing public eye. Is it not significant that Yash Chopra, in a career matching the best of them in span, has made his own brand of socially relevant and clean entertainers with the accent on poetic music? Apprenticing totally professionally under B. R. Chopra’s stern eye, Yash found his budding directorial talents being nurtured by the fact of his eminent elder brother’s instilling, in him, a sense of aesthetics –in the matter of thematically sensitizing the mass use of music by allying its content to the style of verse with which the lay audience could tune. It was to this end that a poet of Sahir Ludhianvi’s brilliance (Naya Daur, 1957) came to succeed the no less illustrious Majrooh Sultanpuri (Ek Hi Rasta, 1956) in the BR camp, just a year after the banner was unfurled. While B. R. Chopra tackled socially relevant themes, Yash was allowed to experiment with a music-accented romantic story-line. This after Yash’s opening gambit, Dhool Ka Phool –as we approached 1960 – focused topically upon pre-marital relations and the plight of an unwed mother (so well played by Mala Sinha).

As Yash grew in confidence, the BR message was quietly passed to him that, given vision, there could be cinema sans music too. The message went so strikingly home that Yash Chopra’s Ittefaq (1969), if his last essay at B. R. Films, turned out to be an even better songless presentation than the elder brother’s Kanoon (1960). Balance, in the art of gearing music to cinema, Yash learnt while being promoted from assistant director to associate director with Kanoon. Young Yash pricked up his ears as B. R. Chopra finished the 1960 screening of Kanoon for his distributors and waited, with bated breath, for their verdict on a venture that his financiers could pronounce to be a non-mover at the turnstiles. ‘Only one question, BR,’ Yash heard the head of distributors saying to his brother, ‘where –in the Kanoon narrative as we have viewed it unravel –are you going to place the songs?’ BR’s comeback: ‘There are no songs recorded for Kanoon to so place! It is a theme that we, at B. R. Films, have designed as a taut whodunit with a social message.’

‘In that case it’s okay,’ Yash enlighteningly heard that head of distributors saying. ‘Don’t touch the unfolding, BR, we are planning to release Kanoon the exact songless way you have presented it to us!’ This was an early career lesson to Yash that, while employing music to enhance the box-office value of a film, he needed to strike a mean in blending Sahir’s song-writing artistry with the gut of the film’s script. Yash was to branch out on his own after 17 highly seasoning years at B. R. Films. As he was directing Gulshan Rai’s 1978 Trishul (starring Sanjeev Kumar, Raakhee, Amitabh Bachchan, Shashi Kapoor and Hema Malini), Yash had reason to remember how a film’s music-making could even hold up the entire narration. Lata and Nitin Mukesh were all set to record a duet to go on fledglings Poonam Dhillon and Sachin in Trishul when, for the first time in the song lexicon of cinema by the Chopra brothers, the Sahir Ludhianvi lyric failed to arrive. Composer Khayyam initially played it cool, knowing how Sahir could surface at the last minute in the case of a lightweight duet whose tune the two had already discussed. However, as a whole hour passed and there was no sign of the Sahir song-lyric, the Trishul unit’s nervousness grew. All the more so as, at a previous recording, Kishore Kumar (with the singer’s mike left unwittingly ‘on’) had been heard to whisper to Lata Mangeshkar that the two should steal out of the backdoor –the day’s recording be damned! As Gulshan Rai fulminated at having to wait eons for the Lata–Nitin song-lyric to reach the recording studio, some nonsensical verse was strung together by Khayyam for the duet–farrago going as: Gaapuchee gaapuchee gam gam kishikee kishikee kam kam.

Trishul, of course, had followed Yash Chopra’s Kabhi Kabhie (1976), a watershed movie never out of the public ear. Khayyam, in fact, kept up the good work via Yash Raj Films’ Manmohan Krishna-directed Poonam Dhillon–Farooque Shaikh starrer, Noorie (1979)–with its Raag Pahadi ‘Lata–Nitin Mukesh–Jan Nisar Akhtar’ catchline of Aa jaa re o mere dilbar aa jaa dil kee pyaas boojha jaa re. No Sahir here, any longer, for a Lata– Nitin Mukesh duet–following that Gaapuchee gaapuchee gam gam 1978 experience in Trishul! For all that, a Khayyam recording is an experience in shared perceptions. I met Khayyam as Pam and Yash Chopra invited me to dinner at their residence on the eve of Kabhi Kabhie’s February 1976 release. Khayyam, on Kabhi Kabhie, was like Dada Burman on Guide. ‘It’s a Yash Chopra story-line that offers me the fullest scope to be tunefully creative,’ enthused Khayyam. ‘I feel my music for Kabhi Kabhie should be providing me with the breakthrough for which I have been waiting all these years. We have some of Sahir’s best poetry, topped by Kabhi kabhie mere dil mein khayaal aataa hai and Main pal do pal kaa shaair hoon, going on Amitabh.’ After a tunefully fruitful tête-à-tête with Yash, with the very musical Pam and the ever tuneful Khayyam, I came to know that they were all set to do the background music of Kabhi Kabhie that very week. What a treat it was to be present during such a happening. As Khayyam musically robed Kabhi Kabhie frame by frame, I felt: ‘If there’s a musical jannat (heaven), surely it is this!’ However, the scene changed swiftly. Changed in the sad follow-up to two Khayyam films of the banner consecutively tanking –Nakhuda (Kulbhushan Kharbanda in the role of Shekhu Dada, 1981) and Sawaal (Sanjeev Kumar-Waheeda Rehman, Shashi Kapoor-Poonam Dhillon, 1982). Outcome –even such a quality composer as Khayyam came to be jettisoned by Yash Raj Films. Thus in came Hridaynath Mangeshkar to compose the music of the Yash Chopra biggie Mashaal (1984) – Waheeda Rehman opposite Dilip Kumar, Rati Agnihotri opposite Anil Kapoor.Mashaal–following Kishore’s Zindagee aa rahaa hoon main (on Anil Kapoor) and that catchy Lata duet with Kishore, Mujhe tum yaad karnaa (on Rati and Anil) –had our diva at last feeling Hridaynath Mangeshkar-vindicated at Yash Raj Films.

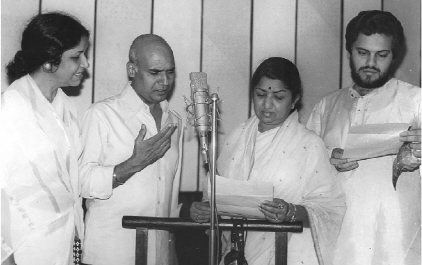

Gaapuchee gaapuchee gam gam –that 1978 Trishul duet saw Lata-Nitin

Mukesh right there, as it was left to the Jagjit Kaur–Khayyam duo to get

things hummingly going

Oddly, it was from Lata bugbear O. P. Nayyar that Yash had absorbed the lesson that you needed to be forthright in fashioning the tone of your film’s music by always making it a point to call the tune yourself. Yash during the making of Naya Daur (1957) had witnessed O. P. Nayyar ‘baiting’ (for a duet with Asha Bhosle) none other than Shamshad Begum in the case of a Raag Bhairavi piece that this superlative performer had been singing all her life –Reshmee salwaar kurtaa jaalee kaa (to go on ‘guest artistes’ Kumkum and Minu Mumtaz in Naya Daur). Yash was sitting by Nayyar’s and recordist Minoo Katrak’s side at Tardeo’s Famous Studios, when he wondered if OP would dare to tell Shamshad how to sing a Punjabi folk tune she knew by heart! Promptly Yash heard OP saying (through the recordist’ smike): ‘Aapa, yoon nahein, aese lo!’ Such O. P. Nayyarized effrontery came as something of an ear-opener to Yash. ‘He was ultra-bold, O. P. Nayyar,’ observed Yash,‘he made you see how important it is to have it done only your way when sitting in upon the music of a film.’

Where O. P. Nayyar was brash, Yash discovered his one-time fixated music director Ravi to be cleverer. Ravi invariably invited Yash to the fully equipped first-floor music room of his West Santa Cruz ‘Vachan’ home to hear his stock of six tunes for the song situation outlined in the case of, say, Waqt or Aadmi Aur Insaan. Yash saw that he got to select his final tune (from the Ravi cluster of six) only inside that composer’s cozy bungalow-home. The balance five tunes always remained on Ravi’s tape, in his own custody, for him to rehash for other producers! Any wonder Ravi never came to score for Yash Raj Films? Also Yash, once he went solo, did not turn too much to Mahendra Kapoor either. Yash, who had seen brother Dharam Chopra content to remain behind the camera – not once summoning the gumption to ask to direct a film–becomingly sought a clean break with the B. R. Films tradition.

In fine, Yash saw merit in Pam’s refusing to go along with the ‘Lata-not-wanted’ syndrome at B. R. Films, grasping the point that any filmmaker should always keep an open mind in picking the main voice while crafting his film’s music. Thus did Yash Raj Films evolve into operating like a corporation, on disciplined lines, with well-defined scripts and tight shooting schedules, making it a point –unlike in the olden days – to deliver on time the finished product to the film’s distributor. It was in such an organized setting that YRF’s Mohabbatein (directed by Aditya Chopra) created A.D. 2000 film history with its accent on the finest in music from Jatin-Lalit, given the duo’s unlimited potential. No wonder every star, by the turn of the century, aspired to do at least one film under the YRF banner for the added value it gave to the performer’s portfolio. For all his later linkage with Amitabh Bachchan-motivated violence, Yash Chopra –in moving from Deewaar (1975) to Trishul (1978); from Silsila (1981) to Faasle (1985); from Chandni (1989) to Lamhe (1991); from Dil To Pagal Hai (1997) to Veer-Zaara (2004) – emerges as the money juggler supreme.

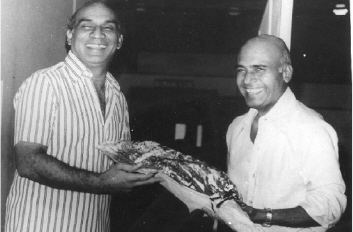

The Kabhi Kabhie aroma:

Yash Chopra greeting Khayyam

I have been a witness to Yash Chopra’s ‘graduating’ from a bungalow to a flat (with wife Pam) and still making spectacularly good on his own steam, in Bollywood, with an undisputed empire of his own. This at a time when my ideal still remained B. R. Chopra, as the one who had given Yash his head, by seeing to it that his assistant director, so full of ideas, got to call the shots, with the megaphone, in every second movie made at B. R. Films. As BR showed me around his then plush-beyond-compare Juhu mansion on the 1973 eve of Dhund’s release, he fondly pointed to one of two huge side-bungalows –on either side of his main central joint family abode. Two side-bungalows so built as for B. R. Chopra –being the eldest in the arena – to be able to act as the Match Referee, announcing through the megaphone: ‘To my left, Dharam Chopra –to my right, Yash Chopra.’ My reference is to the two side-bungalows that BR had ‘dutifully’ built for his two brothers so dear to him. BR, as we walked on, sincerely congratulated me upon having so candidly reviewed Yash Chopra’ smarathon Aadmi Aur Insaan (1969) as ‘an anti-heroine film’ in The Illustrated Weekly of India. Implied in such reviewing commendation was BR’s total disapproval of younger brother Yash Chopra for having concentrated all his Aadmi Aur Insaan energies upon supervamp Mumtaz–as the go-go girl with the come-hither look. This following the movie’s main heroine, Saira Banu, having taken seriously ill and not being able to come to the sets for months on end. After her having completed the shooting of Asha–Mahendra Kapoor’s O neele parbaton kee dhaara (Saira with Dharmendra by the side of a waterfall) and Asha’s Zindagee ke rang kaii re (Saira, looking ever so wan, while riding in a boat).

Before Pam Chopra arrived on the scene to cool things, ‘The Yash of Flaunting Mumtaz’ was as sizzling an affair as any in our gossip glossies shedding more heat than light. The lighthouse here, poetically speaking, was the outhouse to which BR had drawn my pointed attention as ‘a home away from home’ in which Sahir Ludhianvi spent quite a bit of his literary time in Bombay. Recall how Sahir’s Zindagee ittefaaq hai (as put over by Asha) acquired salacious screen overtones on a Mumtaz looking Hindustani cinema’s hottest property in the directorial custody of a Yash Chopra proceeding to revamp Aadmi Aur Insaan, once Saira Banu was rendered hors de combat. No call to go into precise lyrical detail by which Sahir’s poetry underpinned the torrid tone of the Mumtaz–Yash liaison. Suffice it to say that the matter had the healthy aftertaste of Yash Chopra’s leaving Big Brother, for good, to carve out his own King Solomon’s Mines niche in the industry. Guided all along the line by a comprehending wife in Pam. Aspiring young singer Pamela had arrived as Yash’s better half –as one adoring the singing of Lata Mangeshkar all her youthful life –just before the younger Chopra moved from the shade of the banyan tree. A shadow in which Pam saw that Yash could consistently glow but never grow as the true romantic of Hindustani cinema–set to corporate-reign through 37 years (April 1973 to March 2010). The first thing that Pam, therefore, did was to persuade her husband to settle for the divine vocals of Lata in the neo-romantic cinema she planned to have her husband fashioning. After that, Pam’s hand was always to be felt in Lata’s remaining the guardian singing angel of Yash Raj Films.

Yash (having turned 77 on 27 September 2009) is rewardingly free from that confusion which comes with age and tends to prove one’s cinematic undoing. Yash, in fact, is the splendid survivor from his generation of film-makers. Never has he rested on his oars, calmly steering the YRF boat through one storm after another. Thus has he ruled the musical ‘waves’, recognizing song-making as the heartbeat of Hindustani cinema, his hand on the public pulse. Selectively handing over command first to elder son Aditya and then to his younger one, Uday, Yash has enhanced his banner’s VFM (value for money). True Yash Chopra has not directed a film since Veer-Zaara, the 2004 chartbuster so preservably posthumously epitomizing the unrecorded musical oeuvre of Madan Mohan (who passed away on 14 July 1975). Yet, Yash Chopra’s slot as our longest-lasting romantic is secure, following the refreshing new direction he gave to film music as a commercio-art form –by the way he brought, with the 1981 Silsilsa, the mellifluently resourceful Shiv-Hari team into our tuneful fold. As Yash told me –during the release of Kala Patthar (1979) –about how his next film, Rekha–Amitabh’s Silsila, was to be scored by santoor wizard Shivkumar Sharma and fluteace Hariprasad Chaurasia, I frankly expressed my scepticism about the choice. Long hours spent in the recording room had, subconsciously, led to my mentally ‘taking for heard’ the talents of even a sarangi supremo like Ramnarain or a sitar nawaaz like Rais Khan. In fact, I actually told Yash Chopra: ‘Top instrumentalists remain limited in their tuning vision and rarely make the composing cut.’

‘Just you wait and hear Shiv-Hari’s music in Silsila and then corner me if I’m wrong in my pick,’ insisted Yash. Verily had I faltered in my assessment of Shiv-Hari as an inventive duo. They took my breath away with their quality scoring in a clutch of Yash Chopra films, orchestrating theme after theme with sustained audio-visual splendour. I rang santoor emperor Shivkumar Sharma only recently to enquire if it was not this virtuoso playing the tabla in Goldie Vijay Anand–Dada Burman’s Waheeda Rehman-executed Mose chhal kiye jaaye from Guide (1966). ‘Yes, it’s indeed me playing the tabla in Saiyyan beimaan,’ observed Shivkumar Sharma with a touch of pride subtly discernible in one otherwise exemplarily humble. ‘It was Pancham who brought me into the Guide tabla-playing picture,’ revealed Shiv.

‘How then–after a distinctive 12-year run with Silsila (1981), Faasle (1985), Vijay (1988), Chandni (1989), Lamhe (1991), Parampara (1992) and Darr (1993)–did your musical connection with Yash Chopra snap?’ I sought to know from Shiv. ‘There was no real break, you know,’ observed Shiv. ‘It was just that we two, Hari and I, got to be so much in demand the world over–me on the santoor front, Hari on the flute side –that creative coordination with Yash Chopra became increasingly tough. The three of us, therefore, talked it out amicably and decided to terminate the association in total harmony.’

Shiv-Hari had picked up the YRF Silsila baton saddled with no preset poetic baggage to carry in Sahir Ludhianvi (who passed away on 25 October 1980). The team thus felt free to bring in the more contemporary Javed Akhtar to write the Silsila lyrics–for Lata, eminently naturally, to become the melismatic key to the duo’s initially impacting. The Raag Pahadi YRF trail left by Khayyam was, in the duo’s own distinctly creative mould, picked up, in a fascinatingly featherweight 1981 Silsila hue, by Shiv-Hari. A duo sounding so vivid of vein in Dekhaa ek khwaab toh yeh silsile huue (Kishore-Lata on an Amitabh manfully romancing Rekha); Neelaa aasmaan so gayaa neelaa aasmaan so gayaa (Amitabh–Lata tandem on now Amitabh, now Rekha); and Sarse sarke sarke chunariyaa laaj bharee akhiyon mein (Lata, Kishore & Chorus on Jaya Bachchan, Shashi Kapoor & co.). See how, even as Hariprasad Chaurasia himself so inimitably plays the flute in Tere mere hoton pe meethe meethe geet mitwaa (Lata-Babla Mehta on Sridevi-Rishi Kapoor in Chandni, 1989), the duo’s Raag Pahadi base is dulcetly different from that of Khayyam.

In fact, later tuning with Yash’s lucklessly gifted assistant Ramesh Talwar on Sahibaan (1993), Shiv-Hari worked nostalgic wonders with Raag Pahadi by sensitively re-creating Husnlal-Bhagatram’s super 1953 Ansoo duet, Sun mere saajana dekho jee mujh ko bhool na jaana–picturized on the Kamini Kaushal–Shekhar team in Lata-Rafi’s memorable voices (on two sides of the N50220 record). Shiv-Hari arrestingly updated that Raag Pahadi duet, 40 years later (in the evocative voices of Jolly Mukherjee-Anuradha Paudwal), as Kaise jeeyungaa main agar tuu naa banee meree sahibaan (on Rishi Kapoor-Madhuri Dixit in Sahibaan). Raag Pahadi is thus sheer magic in Shiv-Hari’s care, while things are that bit euphoniously different in the Rajasthan folk-based Meghaa re meghaa meghaa re meghaa teraa man tarsaave paanee kyun barsaa re tu ne kis ko yaad kiyaa (Lata & Chorus on Sridevi & co. in Lamhe, 1991). Even Shiv-Hari’s Raag Bhairavi has its own fluid flavour in Mere haathon mein nau nau choodiyaan re (Lata & Chorus on Sridevi & co. in Chandni). If it is Rajasthani Maand you want from Shiv-Hari, you have it, sweepingly, in Mornee baaghaa maa boley aadhee raat maa (Lata on Sridevi in Lamhe). What rivetingly holds the eye, in each one of these Shiv-Hari dainties, is Yash Chopra’ smind-sweeping song picturization, making me ponder if I have not to look beyond Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt, Goldie Vijay Anand and Raj Khosla–into the 80s-90s–for better colour-era enlightenment in this direction. Yash’s ‘taking’ is truly breathtaking by this stage, his camera-placing bearing telling testimony to his neo-technology insights.

Thus the credit for keeping genuine musical values current in our films, through the tuneless and soulless era of 1975–94, should go to Yash and Yash alone. For it is he who made bold to introduce a composing duo of Shiv-Hari’s fibre, as music innovators, at a point when violence was the raison d’être of the cinema in India. Even while doffing his directorial hat to violence as the latest Salim-Javed Esperanto, Yash Chopra never lost his ear for the Khayyam–Shiv-Hari class of music.

Take a bow, Pam Chopra, for your melodious intervention in Yash’s motion picturesque life and times. As the Darby and Joan of our cinema do Yash and Pam come across today, as so Waqt-beguilingly epitomized in Sahir–Ravi’s Raag Pilu-tinted Manna Dey evergreen going on ‘Lala’ Balraj Sahni vis-à-vis Achla Sachdev as:

Ae meree zohrajabeen

Tujhe maaloom nahein

Tuu abhee tak hai haseen aur main jawaan

Tujh pe qurbaan meree jaan meree jaan…