A. R. Rahman leads where others follow. That is because of the singular initiative displayed by this youth icon in implementing the dictum that only dead fish swim with the tide. Rahman created his own tide and the rest is Young India in musical unison … The world turns to Rahman. He no longer bows to the world, working with the kind of flair underlining the credo that, in order to break the rules of musical grammar, you need to master the art of composition first.

If Lata Mangeshkar, as the singer supreme, was decorated with the Padma Bhushan as she turned 40, Alla Rakha Rahman, too, came to be bestowed with the same honour at an enviable age for a composer – 44. Alongside, he clinched two prestigious Grammy awards as we moved into 2010. The very Slumdog Millionaire track, which in February 2009 had won him high international acclaim, scooped its first Grammy for a standout music score. As the cherry on the cake, yet another Grammy gravitated towards Rahman for his Gulzar-penned, Sukhvinder-rendered Jai ho – a Best Song award clinched in rousing competition with the mighty Bruce Springsteen (nominated for The Wrestler from the movie of that name). Jai ho, notably, also made Rahman India’s first to bag a Grammy solo in mainline cinema.

The Slumdog Millionaire soundtrack Grammy had Rahman scoring prestigiously over Steve Jordan (Cadillac Records) and Quentin Tarantino (Inglourious Basterds); as also over the music producers of Twilight and True Blood. Thusdid Slumdog Millionaire(following the score he so tellingly wrote for The Lord of the Rings) signal an enormous growth in Rahman’s world stature. The 12 months starting end-January 2009 thus represented a gold medal run for Rahman as he won the Best Original Music Score and the Best Original Song at the Academy Awards (Oscars);the Best Original Score at the Golden Globe Awards; the Anthony Asquith Award for Best Film Musicat the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA); followed by the Best Compilation Soundtrack & the Best Motion Picture Song at the 2010 Grammy Awards.

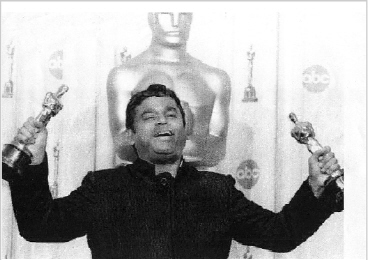

Awards millionaire A. R. Rahman: created his own wave – and how!

An international awards millionaire Rahman thus already is. The number of citations he flaunts is way beyond honours won by any other Indian composer in a musical career still building. Just imagine, the National Award has been bestowed upon this super achiever no fewer than 4 times. Take that with 13 all-India Filmfare awards plus 12 South-based Filmfare awards; 10 International Indian Film Academy (IIFA) awards plus 8 STAR-SCREEN awards. Not to mention 6 Zee Cine Awards, so there is no end to the ‘Rahmania’ gripping the nation. Amidst all this, Rahman, with humility, aptly identified the Padma Bhushan as his most treasured holding. ‘I think I’ve received more congratulations for the Padma than for the Oscars,’ stressed Rahman, so consistently attracting world notice for his creative output in the realm of sound. Rahman’s music, in its foundation, is a reminder of what composer flautist Vijay Raghav Rao said as early as 1978: ‘All experiment in the realm of melody is coming to an end. The future of music lies in sound.’

How sound is the ground on which Rahman stands today? He is the only music scorer from India, so far, to have attained mainstream Hollywood acceptance. That he has managed to win so much, so often, so soon – without indulging in any sort of manipulation whatsoever – is where he stands poles apart from the Shanker-Jaikishans and the Laxmikant-Pyarelals of the mock business that is show business. This scale of achievement impels a fresh look at his career rekhaa. First and foremost, by evoking the Vandemataram mantra in more contemporary orchestrating style, Rahman did something for which the youth of the nation will remain indebted to him for all time to come. In ‘rearranging’ Bankimchandra Chatterjee’s Vandemataram in a strain calculated to instil, in the country’s youth, a new awareness of India as a sovereign state he came to be viewed as displaying a national vision. As Rahman then said: ‘I dedicate this [Vandemataram] album to the future generations of India. I wish that this album inspires them to grow up with the wealth of human values and ethics that this country is made of. I wish that the youth of today would wipe out phrases like “Chaltaa hai”from their vocabularies and find themselves motivated human beings.’

Each word, coming from Rahman’s charismatic lips, was gospel to the country’s youth, so that the mental dent his Vandemataram made is easily imaged on our TV screen. Of course, even here, just nothing would have been possible sans the creative collaboration of Bharat Bala Productions – as headed by BharatBala and Kanika Myer. The team’s creative collaboration with Rahman aimed at vivifying ‘a whole new expression of freedom’. A concept brought home by the stunning visuals that the BharatBala team put together. Visuals arrestingly blending with the neo-dimensional orchestral style in which Rahman re-created Vandemataram. Such was the sweep of these visuals as they came to stirring life under Rahman’s breathtaking baton that it left an indelible impact on the nation’s psyche even while captively capturing the imagination of the country’s young. Befittingly therefore did Rahman go on to thank the Bala–Kanika team ‘for having rescued me from drowning into the sea of film music’.

As the winner of Filmfare’s first R. D. Burman Award for New Music (1995), Rahman, beyond doubt, remembers how someone so sublimely creative as Pancham found himself lost in ‘the sea of film music’, unable to come out of a chakravyuh (whirligig) of his own making. That Rahman should have realized, so early in life, the pitfall perennially inherent in ‘making mere film music’ is a tribute to his insightful thinking. Rahman leads where others follow. That is because of the singular initiative displayed by this youth icon in implementing the dictum that only dead fish swim with the tide. Rahman created his own tide and the rest is Young India in musical unison.

How did the purely Tamil-toned Rahman do it – wonder of wonders – with no Hindi, no Urdu, worth the name? He did it by boldly breaking out of the style-cramping circle that music-making (in Tamil cinema) had become by the early 1990s. As a language with its own ethos, Tamil is not the easiest of tongues via which to make an all-India breakthrough. Such stalwart composers from the South as Viswanathan-Ramamurthy and Ilaiyaraaja had ventured into the quicksands of Hindustani songdom without creating a ripple. By contrast, Rahman made a wealth and variety of music in Tamil – music that compelled instant Hindi dubbing attention. Rahman thus achieved the near impossible by using his initial Tamil songs as the rostrum for creating a firm Hindustani base for himself and his music. Years earlier, in 1965, Salil Chowdhury had ‘gone South’ to craft a noteworthy score for Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai’s Chemmeen– directed by Ramu Kariat for Sheila and Sathyan (in the lead roles) to attract notice beyond the Malayalam ken. Yet no barriers were really commercially broken by the media-celebrated advent of Chemmeen – in the sense that Bombay’s makers continued to remain smugly cozy with their each-Friday doze of star-system flim-flam. It was thus left to Rahman to see that the country’s music enthusiasts got to ‘hear something beyond the Tamil language’ in the 1992–94 songs he composed for their delectation.

His first three films were all in Tamil. Yet the songs from each one of those three movies proved such raging hits that, near compulsively, they had to be dubbed into Hindi, with the original words lingually replicated. Rahman’s Minmini-sung Chinna chinna aasai, when re-rendered by the same performer on the same Roja – played by Hema Malini’s niece Madhu (full name: Madhubala) in 1992 – was a runaway Hindi hit in the shape of Dil hai chhotaa sa chhotee see aasha. In the same Rahman-scored Roja (going on to win for this fresher his maiden National Award), Baba Sehgal and Shweta had us taking aural notice, in spite of ourselves, of Rukmani Rukmani shaadee ke baad kyaa kyaa huuaa – even if this one sounded as inspired by R. D. Burman’s Bhai battoor bhai battoor ab jaayenge kitnee door (Lata on Saira Banu in Padosan, 1968). Three more of Rahman’s Tamil songs transliterated into Hindi – this time as the 1993 Thiruda Thiruda became Chor Chor – caught on instantly, with Young India, in the form of Hum bhee tum bhee chor hain saathee yaad rakhnaa hardam; Pyaar kabhee na todenge saath kabhee na chhodenge; and Chandralekha Chandralekha Chandralekha Chandralekha. Such was the Tamil–Hindi spell cast by Rahman’s tunes that, in a development unprecedented as far as our cine annals go, his 1994 music for Kadhalan took off in the regional format itself, all over India, before the film’s tunes could be Hindi-dubbed: Oorvasi Oorvasi take it easy O orvasi; Muqaabala muqaabala Laila o Laila; and Ennavale adi ennavale enn idhayathai tholaithu vitten! No wonder such a remarkable regional feat ultimately saw Rahman turning into a phenom coming on like a tsunami.

What were the waves made by Hindustani cinesangeet on the international screen before Rahman? However evergreen, our vintage music, till Rahman, had held out a special appeal, at best, to those NRIs beyond India’s borders. Rahman, by contrast, became instrumental in getting all national and international barriers to crumble. Maybe he did it by importing – into his song-making – the slangy, chatty Hindi that our youth came to speak. Maybe the words accompanying a Rahman song even began to influence the colloquializing going with the Hindi that our SMS-oriented youth employed in their everyday speech. Yet the fact is that the world turns to Rahman. He no longer bows to the world, working with the kind of flair underlining the credo that, in order to break the rules of musical grammar, you need to master the art of composition first.

What is it so different that Rahman did? First and fore most Rahman showed our blackmailer singers their places by ensuring that even a performer like him could vocally deliver on the world stage. He changed the rules of the singing game overnight. Till Rahman came through, O. P. Nayyar alone had displayed the gumption to assert that Lata Mangeshkar was eminently dispensable, that Asha Bhosle had the potential to be her match. But where even Nayyar got stuck on Asha in the end, Rahman permitted no singer, coming under his baton, to feel greater than the mike that he put in front of him or her. Just look at the number of fresh singers Rahman has integrated into the fold, where his Hindustani predecessors were content to walk in the playback shadow cast by a select few. No doubt it helped that Rahman came along (with Roja in 1992) as the television revolution was already beginning to grip India. But, within the parameters of the television revolution, Rahman created his own scoring evolution. An evolution seeing our music being computerized to a point of no return. A point of no return to the vintage music we so adored. Saddening as such a development might have been to the old order, it is imperative for such a pre-set listenership to take a less snobbish peek at Rahman’s musical output and discern how his tunes have been as catchy, in their own way, as anything that C. Ramchandra or Shanker-Jaikishan fashioned in their salad days. If these two composers gave orchestration a new direction – at a time when Naushad led in the art of separating ‘instrumentation’ from orchestration – Rahman was different in that, while hearing a song composed by him, the computerized merging was so pinpoint that you could not tell where the composition began and where the orchestration ended! In sum, the tonal vistas explored by Rahman were totally novel. Not until I got down to examining his music more closely did I discern that the broad body of Rahman’s repertoire consisted of tunes I had been – for all my outward apathy – unwittingly hearing through 15 years starting with Mani Ratnam’s Bombay (1995) – without, necessarily, realizing that it was this neo-music maker’s work! Thus did I get a feel of the fact that, where Pancham moved from Bombay to Goa, ‘Chennai Rahman’ had crashlanded in Bombay.

That takes us deeper into the 1995 Bombay terrain of Mani Ratnam, the cineaste who opened up, for Rahman, a parallel Hindi movie to compose (alongside the Tamil original) in the format of a theme grippingly enacted by Manisha Koirala and Arvind Swamy. Rahman agreeably surprised one and all by the aptitude with which he attuned to a Mani Ratnam show – via those nifty numbers going as Kehnaa hee kyaa yeh nain ek anjaan se jo miley (the Ilaiyaraaja-mentored K. S. Chithra on Manisha Koirala); Dil huuaa hai deewaana jhoomta hai mastaana hulla gulla hulla gulla (Anupama Deshpande, Noell, Pallavi S. P. & Shubha as voiced over on Manisha Koirala, Arvind Swamy & co); plus Kuchee kuchee Rakamma paas aao naa (Udit Narayan & Kavita on Arvind Swamy & Manisha Koirala). Of course Mani Ratnam’s treatment was everything in Bombay as it worked wonders in helping Rahman to articulate his art in Hindustani cinema too. The happy result was that he found himself to be totally at home in the 1995 Rangeela atmosphere having Ramgopal Varma so hep-cattily hooked on femme fatale Urmila Matondkar in an Asha-arted vein of Yaaire yaaire zor lagaa ke naache re. This one is readily identifiable as that Asha rendition with which you get to ‘earmark’ the real Hindustani comethrough of Rahman. The sound of music here is so offbeat that, from hereon, there is no overlooking Rahman as the happening-happening thing in Hindustani cinema too. How could we possibly continue to shun Rahman’s music after getting to hear – from the same Rangeela on the same Urmila via the same Asha – Tanhaa tanhaa yahaan pe jeena yeh koee baat hai? Next, it was as his Minsaara Kanavu became Sapnay (in 1997) that Rahman’s Awaara bhanwre jo haule haule gaaye turned into a TV fixation on Kajol (in the voice of Hema Sardesai) – as a film industry-TV musical standoff saw this number being repeated, ad nauseam, on the small screen in our living rooms.

After that, following Ramgopal Varma’s non-running Daud (1997), came Mani Ratnam’s Dil Se (1998) for Rahman to Bollywood-do it in his own musical language. His Chal chaiyyan chaiyyan chaiyyan chaiyyan (Sapna Awasti & Sukhvinder on Malaika Arora Khan & Shah Rukh Khan) and Jiyaa jaley jaan jaley (Lata on Preity Zinta) left a screen stamp of their own. Thus, even as Mani Ratnam – on the artistic side of commercial cinema – again made the South a significant presence on the Hindustani screen, Rahman shot through as a talent in a lane, down which you had to travel with Time. In fact Subhash Ghai’s Taal (1999) and Shyam Benegal’s Zubeidaa (2001) came to underline Rahman’s rise from a regional talent to a nationwide force. Taal is all important as underpinning showman Subhash Ghai’s final switch from settled majors Laxmikant-Pyarelal to neo-viber Rahman. As a blockbuster done in tuneful tandem with Subhash Ghai, Taal had Rahman generating such all-time hits as Taal se taal milaa (Sukhvinder, Alka Yagnik & Udit Narayan on Alok Nath, Aishwarya Rai & Akshaye Khanna); Oye ramtaa jogee oye ramtaa jogee (Sukhvinder & Alka on Anil Kapoor& Aishwarya Rai); and Kahein aag lage lag jaaye (Asha on Aishwarya). For such a razzmatazzy showboy as Subhash Ghai to have turned to Rahman meant a telltale career makeover.

From that 1999 Taal point, it was clear that Rahman, as a musical marvel, had made it on the all-India screen too. His music for Lagaan (2001) was to set the seal upon him as a composer whose aural vision, in the panoramic company of Aamir Khan, took a quantum leap by which Lata, Udit Narayan & Chorus’s O paalanhaare nirgun aur nyaare (on Suhasini Mulay, Gracy Singh & Aamir Khan) left a lasting impression on the big screen. Taken in sync with Ghanana ghanana gir gir aaye badraa (Udit Narayan, Alka Yagnik, Sukhvinder & Choruson Aamir Khan, Gracy Singh, Suhasini Mulay & Raghuvir Yadav) and Radha kaise na jale (Asha, Udit Narayan & Chorus on Gracy Singh. Aamir Khan & co.), the Rahman score gave Lagaan a well-rounded musical look – a look sharpened by Baar baar haan bolon yaar haan/Apnee jeet ho unkee haar haan/Koee hum se jeet na paave/Chalein chalon chalein chalon (audio-visually gripping as it unravels on Aamir Khan & co. in the voices of Rahman & Srinivas).

After Lagaan and Zubeidaa, by the 2002 point in his career, Rahman’s fame had stretched to Andrew Lloyd-Webber’s Bombay Dreams, the play opening so jazzily in London that year. On the cine scene, Rahman began touching his zenith with Mani Ratnam’s Yuva and Ashutosh Gowariker’s Swades (both 2004). Yuva carried its own individual appeal via the catchily atmospheric Fanaa fanaa fanaa fanaa (Rahman& Sunitha Sarathy on Kareena Kapoor & Vivek Oberoi) and Kabhee neem neem kabhee shahd shahd (Madhushree & Rahman on Abhishek Bachchan & Rani Mukerji). Swades, for its Ashutosh part, was memorable for the eye-pleasing, ear-catching Yeh taara woh taara har taara (Udit Narayan on Shah Rukh Khan); Saanwariya saanwariya tuu ne dil moh liyaa (Alka Yagnik on Gayatri Joshi); and Yoon hee chalaa chal raahee (Hariharan and Udit Narayan on Makarand Deshpande & Shah Rukh Khan).

The long-awaited Rahman–Aamir Khan re-connect got to be resonantly effected (come 2006) through Rang De Basanti – opening words of the film’s theme song, by Daler Mehndi & co., as voiced over on Aamir Khan & co.; Khalbalee hai khalbalee (Rahman, Nacim & Mohammad Aslam on Siddharth, Aamir Khan, Kunal Kapoor & Sharman Joshi); Rubaroo rubaroo roshnee hai (Rahman & Naresh Iyer on Aamir Khan, Sharman Joshi & co.); and Mastee kee paathshaala (Naresh Iyer, Mohammad Aslam & co. as they come ‘voiced over’ on Aamir Khan, Sharman Joshi, Kunal Kapoor, Siddharth, Alice Patten & Soha Ali Khan). By way of a fitting Rang De Basanti follow-up came Rahman–Mani Ratnam’s Guru (2007) to leave its vivid vocal imprint via Barso re meghaa meghaa (Shreya Ghoshal on Aishwarya Rai).

How unputdownable a musician Rahman was by this stage should be manifest from the advent of Sivaji, in 2007, and Jodhaa Akbar in 2008. While the Tamil Sivaji found Rahman to be in his composing element, Jodhaa Akbar – if raising a genuine critical doubt about Rahman’s Mughal musical bonafides – found his score for the theme (liberally borrowed, ‘in the background’, from Ravi Shankar’s 1979 Meera!) to be winning instant populist support. That is but a way of saying that Rahman’s musical comfort level was far greater in a same-2008-year show like Jaane Tu …Ya Jaane Na – with its familiar rhythm of Kabhee kabhee Aditi (Rashid Ali on Imran Khan vis-à-vis Genelia D’Souza) and Pappu can’t dance (Aslam, Tanvi, Blaaze, Naresh Iyer & co. on Imran Khan, Genelia D’Souza & co.). After that we move spectacularly to Aamir Khan’s Ghajini (2008) with its hummable rhythm of Behkaa main behkaa o behkee hawaa see aaye (Karthik on Aamir vis-à-vis Asin) and Meree adhooree pyaas pyaas (Sonu Nigam on Aamir Khan). From there we go into Rahman’s Jai ho hall of fame via Slumdog Millionaire – no call to gild the lily here. But touch we must on Delhi-6 (2009) with its captivating catchline of Masakali masakali ud matakali matakali (Mohit Chauhan on Abhishek Bachchan & co.) alongside Saiyyan chhed deve nanand chutkee leve sasural gendaa phool (Sujata Majumdar, Rekha Bharadwaj & Shrradha Pandit on Gracy Singh, Supriya Pathak & Waheeda Rehman).

What a musical range to have spanned in 18 years! Despite this, an entire generation feels that Rahman has mercilessly mercenarized music. There I have to agree. I also have to agree that, in this Tamil Muslim’s musical vocabulary, there does not seem to be, regrettably, any real slot for classical Urdu. No wonder that, on the odd occasion witnessing a Zubeidaa ora Jodhaa Akbar coming along (in the 2001–08 frame), Rahman was observed to be ill at lingual ease. Take(so well shot in Shyam Benegal’s Zubeidaa) Rahman’s exemplarily soft-veined Dheeme dheeme gaaoon dheere dheere gaaoon haule haule gaaoontere liye piyaa (Kavita on Karisma);or his no less tender Mehkee mehkee hain raahein behkee behkee hain nigaahein hai naa(Alka Yagnik&Udit Narayanon Karisma&Manoj Bajpai). Well as these two numbers (written by Javed Akhtar) finally come over on the Zubeidaa screen, getting his Urdu act together proved no piece of cake for Rahman. Yet it is not so much Zubeidaa (2001) as Jodhaa Akbar (2008) that raised serious queries about the young man’s music being ethnically Urdu-rooted, as Kehne ko jashn-e-bahaaran hai (Javed Ali voiced over on Hrithik Roshan vis-à-vis Aishwarya Rai) and Khwaja mere khwaja dil mein samaa jaa (led by Rahman himself) left music connoisseurs cold. That is, the connoisseur attuned to the Naushad–Roshan–Madan Mohan– Khayyam idiom of Hindustani cinesangeet.

That is as it may be, yet his critics, I feel, are not being totally fair to the young radical by being habitually dismissive of the music this Madras mould-breaker has so successfully made, on the Hindustani screen, through a decade and a half. Let us not forget that a music prodigy takes roughly 20 years to settle into a groove. It is a growth process by which such an idol, ultimately, becomes identifiably groovy in his métier. That is to say, it is only as Rahman begins living down his being a youth icon that the real musicperson in him could begin to assert itself. By that stage this maturing composer might or might not find the scale of public adulation he presently enjoys. But the journey by which he goes on to tap the real reservoirs of his musical strength should be worth watching. Rahman might yet surprise us with his staying power, with his storehouse of musical creativity. He is hugely gifted. Enormously creative. In the cutthroat world of the Oscar and the Grammy, you do not win through, unless you are powered by a certain magnitude of talent. Clearly the music Rahman evokes is of a genre with which the West also empathizes. How else do you explain his making it to the TIME magazine’s 100-strong listing of the ‘World’s Most Influential People’?The news magazine even zeroe din upon Rahman’s theme music for Mani Ratnam’s 1995 Bombay as ‘one of the 100 albums to listen before you die’!

Truth to tell, Rahman has reached, in his career, a point where you wonder which is the peak left for this wunderkind to scale, following his 2009 collaboration with legendary Aussie popstar Kylie Minogue (in Blue) on Chiggy wiggy. As another popstar Bryan Adams put it – in jargon summing up the Remo Fernandes-sung Hamma Hamma Rahman topper from Bombay (1995) – a topper going, for starters, as, Ek ho gaye hum aur tum: ‘If you haven’t heard this song in the last 15 years, I don’t know which rock you’ve been hiding under!’ That is the beauty of music as Rahman gets a true feel of the fact that, in shimmery showbiz, the more you achieve, the more there is left to accomplish! It is by this stern yardstick that Rahman is going to be measured from the 2010 double-Grammy, double-whammy stage in his career. It is a time when, musically exploring, Rahman dismayingly discovers that he has to dare even more than before. At a point in his tuneful odyssey when the possible price to be paid, for such daring, could be loss of his eternally youthful following. A following fluidly summed up by the total simplicity of wording and the limpid lucidity of scoring that Rahman brings to the ‘pining-for-Manisha’ Arvind Swamy–A. Hariharan presentation of a Bombay tune thematically symbolic of a style set to change the very tone of Hindustani film music in the decade and a half to come:

Tuu hee re tuu hee re tere binaa main kaise jiyun

Aa jaa re aa jaa re yoon hee tadpaa na tuu mujh ko

Jaan re jaan re ein saanson mein bas jaa tuu

Chaand re chaand re aa jaa dil kee zameen pe tuu…