The fate of such a classic [as Mera Naam Joker, 1971] left Raj Kapoor with no option but to reinvent RK …. It meant going back to Lata Mangeshkar and paying that diva her till-then-denied RK royalty. Lata, for her royal part, demanded, by way of a further recompense, the instant sacking of Shanker and the RK debut of ‘my boys’ Laxmikant-Pyarelal. Raj caved in…

The history of being Raj Kapoor is surely something more than the geography of viewing Zeenat Aman through the lascivious eye of the RK camera? Before taking a closer look at Zeenie Baby’s being all female form and no theme content (in RK’s Satyam Shivam Sundaram, March 1978), I would like to disc-record the fact that, in my eyes and ears, Raj Kapoor remains the greatest ever audio-visionary in the song vocabulary of Hindustani cinema. I know Guru Dutt rooters would be up in arms. But the cardinal aural difference between the two is that while Raj Kapoor okayed the tune on the spot, not once going back on his choice, Guru Dutt was never ever sure of the tune he ‘passed’. He could – and generally did – change it the following morning.

Guru Dutt needed to shoot the songless part of the movie first – beyond doubt ultra-ultra imaginatively – before ‘visualizing’ the tune as blending with the weave of the theme, something which certainly made him our finest song ‘taker’. But not our surest song ‘maker’. This ‘credit title’ goes to Raj Kapoor, and Raj Kapoor alone, for he was gifted with ‘that inward eye’ by which he could conceptualize the entire theme, all sinew, as an already musicalized narrative – before sitting down to okay the tune. The song situation came flowing into the stream of the RK theme as the story-line unfolded. Where exactly the two merged, Raj alone knew. That is why the moment Pancham (R. D. Burman), a total musical stranger to Raj Kapoor, played his first-ever tune before him, he got an instant and a permanent okay to Eik din bik jaayega (composed for Dharam Karam, 1975). The words would come later. They always did with Raj who never okayed a tune unless it came mentally floating into the RK narrative, which was already running in the camera of his mind. On my view screen, therefore, ‘Goldie’ Vijay Anand was, truly, the only other personality, in our cinema, gifted with Raj’s theme-embracing audio-vision. Goldie, like Raj, had ‘style’, musical style. Yet this ‘style’ was Goldie’s very own. It had absolutely nothing in sync with Raj’s ‘style’.

Raj Kapoor rarely went wrong in his audio-vision. When he did, you got a Zeenat Aman in the avatar you did. Zeenie contrived to so entice Raj Kapoor for the Satyam Shivam Sundaram role that it came to sex-symbolize RK’s one sad-sack pick of a heroine.

In a sense, it all began as Raj bent Nargis to his emblematic RK violin-will in Barsaat to be followed by a record 13 Raj–Nargis films in a row. Yet, by end-1956, all seemed over between the two bar the sinking of Jagte Raho. The critically acclaimed Jagte Raho came, with a dash of irony, after AVM’s Chori Chori had been lapped up as just the escapist style of Raj–Nargis calflovey-dovey show with which our eternally fantasizing audience tuned. The losses Jagte Raho inflicted upon RK saw the banner in the red by beginning-1957. Yet RK’s staff continued to receive their salaries at the end of each month. Generous to a fault was Raj Kapoor. Hasrat Jaipuri’s name had emerged as RK’s song-writer since 10 March 1950, the date on which Raj-Nargis really arrived as the nation’s neo-romantic team with Barsaat, the film in which we saw Nargis running into Raj’s violin-playing arms – for the RK emblem to take shape – as Raj proceeded to ‘shape’ Nargis to his willowy whim. Four decades after Barsaat materialized, Hasrat was to tell me that, a full 14 years following his ceasing to be professionally active at RK in the aftermath of Kal Aaj Aur Kal (November 1971), Raj Kapoor paid him a handsome amount. That too for just one song, from his Shanker-Jaikishan stock, carried into Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985). This bonus payment, emphasized Hasrat, came unsought. It came as the Hasrat-written, Jaikishan-tuned, Lata-rendered number, Sun saahiba sun, turned out to be the greatest draw in RK’s Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985).* Sun saahiba sun was picturized on debutante Mandakini in the crucial varmaala sequence almost determining audience acceptance or rejection of the movie’s theme. The song was proclaimed by HMV to be 1985’s smash topseller. Whereupon Raj Kapoor came up with that spontaneous bonus payment to Hasrat – for old times’ sake! Hasrat recalled that Sun saahiba sun had originally been written for RK’s never-made Ajanta, a song contribution for which he had already been paid.

A Raj bending Nargis to his violin-will

Much has appeared over the last couple of years about Raj Kapoor, when the man cannot speak up for himself. First, there was Dev Anand autobiographically moaning (in his Romancing with Life, Penguin, New Delhi, 2007) about how Raj Kapoor had spirited away Zeenat Aman from under his Navketan nose. The way Dev came through in his plaint, he alone seemed to be still in the dark about his Zeenie Baby’s having switched camps. Zeenie herself had effected the RK crossover in a style calculated to leave no one, least of all her Dev, in any doubt.

Alongside came the surprise ‘revelation’ by Kishwar Desai in her book, Darlingji: The True Love Story of Nargis and Sunil Dutt, (HarperCollins, New Delhi, 2007), that Raj Kapoor pursued Nargis much after she had walked out on him. Well, well, that is certainly not the way we – who were on the spot at the time – saw it. For these Darlingji charges to be hurled at Raj Kapoor, after he has left us, is not being fair to the man and his cinematic vision. I dare say I knew Sunil Dutt even better than I did Raj Kapoor. All the complexes Sunil Dutt developed, as outlined in Darlingji, had their genesis in one single newspaper headline. A headline carried the day after Nargis and Sunil Dutt belatedly decided – after the much-hyped advent and highly acclaimed success of Mehboob Khan’s Mother India in October 1957 – to make public the fact that the two of them were already man and wife. The announcement (delayed by months at Mehboob’s request) first came to be made, becomingly, in India’s No. 1 newspaper: The Times of India. On that fateful marriage-announcing morning, the paper carried the male ego-shattering headline: Nargis Weds Sunil Dutt. In vain was it pointed out by us to The Times of India News Editor D. F. Thomas that, in keeping with newspaper tradition, the heading had to be: Sunil Dutt Weds Nargis. ‘Who’s Sunil Dutt? Readers know only about Nargis!’ was News Editor Thomas’s startling response. That is how, regrettably, The Times of India headline remained as it was. That is where Sunil Dutt developed a terrific complex from the word go. That is how the Nargis–Sunil vibes started going wrong at the outset itself. The rest is Darlingji history.

In the wave-making wake of the Darlingji controversy came the Vyjayanthimala claim, in her Bonding: A Memoir (Stellar Publishers, New Delhi, 2007), that there never was any Bol Radha bol Sangam-affair between Raj Kapoor and her, something on which both Rishi Kapoor and Randhir Kapoor (Raj Kapoor’s sons) had the gumption to take on Vyjayanthimala. Summing it up best is Main kaa karoon Ram mujhe budhdha mil gayaa– as so ‘expectantly’ executed by Vyjayanthimala before an ogling Raj Kapoor in Sangam (1964). If Jaikishan tuned both Bol Radha bol and Main kaa karoon Ram for Sangam, he did so in a setting by which that playboy well knew a sizzling affair to be on, right then, between Raj and Vyjayanthi. Raj actually broke with RK norm by choosing Jaikishan, not Shanker, to tune the Bol Radha bol theme song of Sangam – in ‘RK Bhairavi’. Raj next got the same Jaikishan to tune and record, in the vibrant voice of Mohammed Rafi, Hasrat’s Yeh meraa prempatra padh kar, set to be picturized on neo-superstar Rajendra Kumar. One thing about Raj Kapoor – he led his private life almost in public. He always was refreshingly open about it all.

Those were tempestuous times when, while Raj was RK-ritualistically ‘on’ with Vyjayanthimala, Rajendra Kumar, as India’s No. 1 superstar, was having a hectic affair with the nubile Saira Banu. So hectic that their 1964 Ayee Milan Ki Bela had Jaikishan attuning Tum kamsin ho naadan ho naazuk ho bholee ho to Saira–Rajendra’s prodigal proximity. Also, Rajendra Kumar was at his megastar peak when Yeh meraa prempatra happened. The music of Sangam was SJ-chiselled to underscore the torrid Raj–Vyjayanthi tuning during the most tumultuous phase of the Kapoor boy’s lady-killer career. Remember that, following the late-1956 break with Nargis, from the ultra-daringly projected Padmini did Raj turn to the no less provocatively got-up Vyjayanthi in the 1957–64 span. A Vyjayanthimala coming to Raj on the 1961 Gunga Jumna-Dilip Kumar rebound – for Sangam to emerge as a 1964 RK film in which Raj’s ‘show womanship’ matched his showmanship.

Jaikishan: Shanker’s choice Raj endorsed

The Sangam score, in its totality, underlined Raj Kapoor as a musicperson of rare romantic seasoning by the mid-1960s. In fact, Raj once looked composed as a singer too. Freedom at midnight and mid-August 1947 found Raj Kapoor striving to be a singing-star. As Madho opposite Madhubala playing the Rajkumari in Dil Ki Rani, Raj rendered, in that 1947 movie, a full song all by himself – tuned by S. D. Burman and penned by Yashodanandan Joshi as O duniyaa ke rehne waale bataa kahaan gayaa chitchor. Why Raj determined that this would be his first and last song in films is a mystery, when he sang it rather well. Far better than Dilip Kumar did Laagee naahein chhoote Rama chaahe jiyaa jaaye (with Lata) in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s 1957 trilogy: Musafir.

India’s breaking free certainly witnessed Raj Kapoor as enlarging his cinematic vision by launching RK with Aag opposite Nargis, Kamini Kaushal and Nigar – the more women, the merrier! Aag also had, more pertinently, Raj latching on to Mukesh, by 1948 itself, via Zindaa hoon is tarah kee gham-e-zindagee nahein. Side by side (during the 1948–49 phase), while performing opposite Nargis in Mehboob’s Andaz, Raj discerned that his ‘own Mukesh’ had just emerged as the voice of Dilip Kumar (opposite his own Nargis) via Mela, a golden jubilee hit as scored by Naushad in 1948. Also that Mukesh would next, under the same Naushad, only go on to fortify his position, as the voice of Dilip Kumar, in Mehboob Khan’s ambitious Andaz (1949).

Raj Kapoor, in Andaz, had but a measly Rafi–Lata duet opposite Nargis (Yoon to aapas mein bigadte hain). All four Mukesh solos, in that prestige Mehboob film, had been audio-visualized by Naushad to go on Dilip Kumar, piquantly playing the piano. Sequentially, Hum aaj kahein dil kho baithe in Raag Jaijaiwanti, Tu kahe agar jeevan bhar in Raag Kirvani, Toote na dil toote na in Raag Bhairavi, not least Jhoom jhoom ke naacho aaj in Raag Pilu had Dilip Kumar Andaz-wooing Nargis, piano caressingly, to a point of virtual ‘no Raj return’. Yet Toote na dil toote na (in Naushadian Bhairavi) gave Raj an idea. An idea that took wings as Raj sensed that Lata Mangeshkar, under Naushad, was all set, by April 1949, to take off on Nargis, in Andaz, via Meree laadlee ree meree laadlee ree banee hai (in Raag Bilawal), Uthaye jaa unke sitam (in Raag Kedara) and Tod diyaa dil meraa toone (in Raag Pahadi). This was the moment in which Raj discerned that, as distinct from the Naushad raagdaari, he had to create his own patent Bhairavi, via the same Lata and Mukesh, in his own Barsaat (by the time it got to release in 1950). A rebel film in which his own finds, Shanker-Jaikishan, would craft the theme’s ultra-romantic music, exactly as Raj himself envisioned it. Just absorb, afresh, SJ’s RK-directed music for Barsaat. A ‘youth’ film seeing Raj getting Shanker-Jaikishan to spin out no fewer than five of the ten songs in ‘RK Bhairavi’ – Barsaat mein hum se milen tum sajan, O o o o mujhe kisee se pyaar ho gayaa, Chhod gaye baalam, Ab meraa kaun sahaara and Main zindagee mein hardam rotaa hi rahaa hoon. Was it not Ameen Sayani who coined ‘Shanker-Jaikishani Sangeet’ as the Binaca Geetmala catchline? Let us amend that to ‘Shanker-Jaikishani Bhairavi’– the sada suhaagan raag!

The ‘Shanker-Jaikishani Sangeet’ that Raj so evocatively created lives on through RK – a banner we associate with the ‘dream sequence without musical parallel’ in the glossary of Hindustani cinema. Take your Raag Bhairavi choice, here in Awaara (December 1951), between Shanker’s Tere binaa aag yeh chaandnee and Jaikishan’s Ghar aayaa mera pardesee. What artistry of orchestration, what pedigree of composition! No wonder Raj Kapoor insisted that there is no such thing as an ‘SJ Bhairavi’, that there is only an ‘RK Bhairavi’. What is Mukesh’s Awaara hoon if not ‘RK Bhairavi’? Awaara hoon, in fact, took Raj zooming to a new Russian summit. The Raj–Nargis team became two-in-one in Soviet eyes.

But good times are not forever. There was a troubled phase in RK’s evolution as Raj–Nargis’s Aah (1953) tanked and Boot Polish (January 1954) remained, at best, a neo-realistic side-show. It was an experimental film with which Raj Kapoor had gone ahead, after he inspirationally viewed (in June 1953) Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin and exulted: ‘I wish I had made it!’ Only RK insiders know that, originally, there was not a single song in Boot Polish and that each one of the seven numbers that one got to hear was in the nature of a Raj Kapoor afterthought! Not a very happy afterthought, true, for an audio-visionary who could mentally envisage his film’s music as happening only alongside the RK narrative. When Nargis–Raj’s Aah arrived (in May 1953) as the first romantic box-office setback for this perennial RK pair, the songless Boot Polish – already shot fully as a Vittorio de Sica style of stark neo-realistic film – naturally came up for a ‘re-view’. Raj had lost heart after Aah came romantically unstuck. Nargis, her feet still on the ground, suggested that no further risks be taken and straightaway a few songs should be added to the starless Boot Polish to make it a more viable box-office proposition. This line of thinking went against Raj’s cinematic grain, yet he had no choice but to accept Nargis’s timely counsel.

What is it if not the genius of Raj Kapoor that, not even in one such song situation, did we viewers get to realize that each tune we heard, in Boot Polish, was a second thought! That each song was an interpolation inventively woven into the narrative, after the entire film had been already songlessly shot by director Prakash Arora. Even that Raj Kapoor personal Awaara hoon appearance, inside the Boot Polish train, was an ‘aftertouch’! Shanker-Jaikishan came into the Boot Polish picture late, very late. Young and enthusiastic, they tackled such an unusual challenge with gusto. Inside 25 days of the maximum one month RK allotted, this magic duo had composed, rehearsed and recorded all seven Boot Polish songs to the total satisfaction of Raj Kapoor. Songs going as Raat gayee phir din aataa hai (Manna Dey, Asha Bhosle & Chorus), Nanhe munne bachche teree muththee mein kyaa hai (Mohammed Rafi, Asha Bhosle & Chorus), Thehar zaraa o jaane waale (Manna Dey, Asha Bhosle & Madhubala Jhaveri), Lapak jhapak tuu aa re badarvaa (Manna Dey & Chorus), Chalee kaun se desh gujariyaa (Talat Mahmood-Asha Bhosle), Main bahaaron kee natkhat raanee (Asha Bhosle) and Tumhaare hain tum se dayaa maangte hain (Mohammed Rafi, Asha Bhosle & Chorus). Inside those 30 days, Raj Kapoor, sitting through the night with SJ, completed the Boot Polish background music, too, to get the film to go (for an easy passage) before the censors on the last day of 1953 – in the very year in which the Aah losses had mounted.

Like Chaudhwin Ka Chand (1960) after the 1959 Kaagaz Ke Phool box-office disaster in the case of Guru Dutt-Waheeda Rehman, Boot Polish certainly brought in enough moolah, by March 1954, for Raj-Nargis to be back, memorably, on their regular romantic romp with Shree 420 (1955). Thus even Aah was but a momentary glitch. Before that, Awaara (1951) had made Raj-Nargis inseparable, as a pair, in the public eye. The happening-happening pair of Nargis-Raj Kapoor was to fetch Shanker-Jaikishan (outside the RK fold) their first-and-last genuinely earned Filmfare Best Music award for AVM’s Chori Chori (1956).

Chori Chori saw Shanker-Jaikishan compulsively having to go without Mukesh on Raj Kapoor. Why? RK’s Shree 420 all but had Mukesh yielding the highly coveted Raj Kapoor vocal crown to Manna Dey. Reflect, in the circumstances, upon those two Shree 420 early-recorded numbers with which Mukesh still stayed ‘live’ on Raj Kapoor – Meraa jootaa hai Japani and Ramaiyya vastavaiyya, both tuned by Shanker in Raag Bhairavi. Remember how, in the same Shree 420, Manna Dey had created his own distinct impact, on Raj Kapoor, with Dil ka haal sune dil waala, Mud-mud ke na dekh and Pyaar huuaa ikraar huuaa – all three, yet again, tuned by Shanker. How Manna Dey came into the RK picture is a story in itself. Shanker grew jittery as Raj nodded assent to only the fifth of six tunes he had, according to set norm, done for that key opening Meraa joota hai Japani situation in Shree 420. The day following was the recording for urgent picturization that very week-end, of the crucial double-sided bustee theme song to be shot in the Lower Parel slum of Bombay, leading up to the Shree 420 climax.

Accordingly, early the following morning, Shanker – for the first time a trifle nervous – projected, before Raj Kapoor, his six tunes for that Shree 420 situation, a situation designed to create the mood for the K. A. Abbas theme’s climax, pitting the have-nots against the ‘have-notes’. Shanker had barely started playing, when Raj Kapoor pounced upon his very first tune, pronouncing it to be just what he needed. A tune okay, with Raj, down to the point of retaining, untouched, that pleased-as-Punch composer’s dummy Ramaiyya vastavaiyya wording. How swiftly Shanker’s sense of confidence, so shaken the previous day, returned, as Raj patted him on the back, saying he always knew his Gendaa Master could do it. (Raj had nicknamed him thus for the rhino-like way Shanker habitually got his head stuck into preparing those six tunes for his chief to be able to take his choice.)

Gendaa Master Shanker was thus fully in control, mentally, as Raj Kapoor asked him to summon Rafi, Lata and Mukesh for rehearsal. Following the song’s racy rehearsal and totally harmonized recording, Raj Kapoor was flabbergasted as Mukesh blithely told him that Ramaiyya vastavaiyya, coming just after Mera jootaa hai Japani, would be his last two numbers to go on Raj Kapoor for some time to come, following his personal appearance in RK’s Aah, enacting (as the tonga driver) Chhotee-see yeh zindagaanee re. Reason for such unavailability? Mukesh had signed, on the perforated line, as Suraiya’s singing-star hero in Mashuqa (censored by end-January 1953 but failing to find a release for months on end). Such signing, behind Raj’s Shree 420 back, had followed the exceedingly handsome Mukesh’s, side by side, falling for the ultra-comely lady producer of Mashuqa, a beauty claiming royal descent! To quote from Mukesh’s letter (dated 23 September 1953) to his ardent fan Mohan Goel:

Ramaiyya vastavaiyya … Seldom had Raj Kapoor to scratch his head for a tune-idea with theme-song specialist Shanker on the job

My Dear Mohan

Here is a copy of my autographed photo for your album. No one can be more alive than I am to the fact that there are few gramophone records of mine in circulation. And this realization is not a comfortable one. It disturbs me terribly. But there were reasons, some of them pretty unfortunate, that landed me into this unhappy position. This downward trend started when, stupidly enough, I put my signature on the contract of Mashuqa which, among other things, prevented me from giving playback songs so long as the picture was not finished. (Italics added.)

Now that film took an exceptionally long time to complete, thus throwing me out of the news. I was expecting that I shall regain my place after Mashuqa gets released. But even there a disappointment awaited me. That picture never came on the screen save in Bombay where it had a frightfully short run. This completed my misfortune, and I drifted further away from the liking and demands of my fans. Now I am making a bid to recapture my popularity by producing a film of my own and singing my way again into the hearts of my fans. I have named it Anuraag. You can look forward to its early release in your home town. Pray to God that it may be well received and it brings me back the love of millions of my fans.

Yours sincerely

(sd) Mukesh

Raj had every reason to be livid with Mukesh, if only because RK had commenced recording for Shree 420 ultra-early, only to find his pet voice not available to him, after his ‘soul’ singer had done just two songs for that film. That Shree 420 ultimately benefited Mukesh and Manna Dey alike was a happy denouement. That Shree 420 simply endeared Raj-Nargis, all over again, to the nation’s youth is but a reflection of how these two came to rewrite the very grammar of love making in Hindustani cinema.

Who then knew that Nargis was to go out of Raj Kapoor’s life soon after the release of Chori Chori (October 1956)? Following such a cataclysmic split, the Jagte Raho RK climax, as shot by the neo-realistic Bengal team of Sombhu Mitra and Amit Moitra, took some selling to the everyday audience. Jaago Mohan pyaare, for all its Raag Bhairav sculpting by Salil Chowdhury, was not the style of Raj–Nargis ending that their adoring fans were thirsting to view. Not after having just been thrilled by the ultra-romantic musical runaway rove of Chori Chori. Moreover, such had been the RK musical ethos that viewers had confidently anticipated Shailendra’s masterfully written Zindagee khwaab hai to be going, in Jagte Raho, on actor Raj Kapoor, rather than on character actor Motilal. A recipe for Raj–Nargis disaster was what Jagte Raho, in essence, turned out to be. The film’s advent and descent saw Nargis ceasing to be a part of the creative RK side. As that happened, Raj Kapoor faltered. He began playing the hero, mindlessly, in a number of films outside RK – ‘just for the money’. RK’s next Jis Desh Men Ganga Behti Hai (1961) was a full five years in the Padmini-smitten making. Padmini’s overtly saucy sexuality, Raj’s evocative etching of the complex dacoit-centric theme, plus his carrying-off of Raju’s role so convincingly, did help give the show a box-office fillip. But, minus the level-headed Nargis at RK – to control Raj’s known predilection to overshoot and, generally, overspend – Jis Desh Men Ganga Behti Hai, even while doing so well with the Shanker-Jaikishan team scoring notably yet again, could not quite balance out the RK budget. Things were in order so long as Shanker was creating O jaane waale mud ke for Nargis in Shree 420 (1955). Not by the time Jaikishan was shaping O basantee for Padmini, five years later, in Jis Desh Men…. Even Sangam, in the face of its being pronounced as the industry’s biggest box-office hit till end-1964, made it touch-and-go at RK. All the more so as the Raj Kapoor–Vyjayanthimala off-screen bonhomie led to a major disruption in the Kapoor family.

The after-Sangam RK scene is even bleaker. With no Vyjayanthimala-like sex object to ignite audience prurience, Mera Naam Joker, six marathon years in the unmaking, set the fully mortgaged RK back – on Raj Kapoor’s own published admission – by a whopping Rs 56 lakhs, an astronomical sum to be losing in 1971. Asha Bhosle was not an RK patch on Lata Mangeshkar, something Raj divined too late. Asha’s Ang lag jaa baalama (as tuned by Shanker) had a pathetic Padmini-played-out ring about it. Her dueting in Daagh na lag jaaye (by Jaikishan) and Kaatey na katey raina (by Shanker) just failed to register on viewers having no eye for an ultra-buxom Padmini looking, at best, an old Raj flame no longer burning bright. Even Raj’s own Mukesh failed to work the miracle in Mera Naam Joker. Neither Shanker’s Jeena yahaan marnaa yahaan nor Jaikishan’s Jaane kahaan gaye woh din helped give Mera Naam Joker an instant boost, well as the film’s music might have fared on record. Shanker’s Kehtaa hai joker and his Manna Dey-Filmfare award-winning Ye bhaai zaraa dekh ke chalo, likewise, failed to spot-lift the show.

Manna Dey’s winning the Filmfare Best Singer award so late in his performing life (1971) – the fact of its being of little use in furthering his career – is my opportunity to spotlight the importance of this particular statuette in big bad Hindustani cinema. A Filmfare award, through 58 years going into 2010, is somehow the be-all and end-all of glossy recognition in Mumbai’s multimillion movie industry. Not that other awards do not count. They do. But they matter largely in terms of prestige. Where it comes to pure commercial advancement in a mammon-driven industry, a Filmfare award – given the backing of institutional tradition – remains the password of passwords. For all that, the question is: When does a Filmfare award help you move forward? The 1971 Filmfare Best Director award to Raj Kapoor and Best Music Director statuette to Shanker-(Jaikishan), both for Mera Naam Joker, meant little at this calamitous 1971 RK-point. True, Mera Naam Joker rates as an RK–SJ milestone. But a millstone around Raj Kapoor’s neck is what it became. The fate of such a classic left Raj Kapoor with no option but to reinvent RK in the mermaidenly Lolita shape of Dimple Kapadia playing Bobby (1973). It meant going back to Lata and paying that diva her till-then-denied RK royalty.

Daagh na lag jaaye … As Asha replaced Lata at RK with Mera Naam Joker (1971), Shanker-Jaikishan and Raj Kapoor gave it all they had – to no avail, as the showman’s film flopped like nobody’s show business. Picture shows (L to R): Shanker, Asha Bhosle, Jaikishan and Raj Kapoor

Lata, for her royal part, demanded, by way of a further recompense, the instant sacking of Shanker and the RKdebut of ‘my boys’ Laxmikant-Pyarelal. Raj Kapoor caved in, sensing that the eternal vocals of Lata alone could evoke the ‘thrush-thirteen’ effect he needed on the oomphoozing Dimple, playing Bobby opposite the Mills & Boon Rishi Kapoor. Hum tum ek kamre mein bandh hon, Jhoot boley kauva kaate, Akksar koee ladkee, Mujhe kuchch kehnaa hai – if these are tunes that have a Shanker-Jaikishan overlay, they also carry the Laxmikant-Pyarelal finishing touch. Yet the first thing Raj Kapoor told the Laxmikant-Pyarelal duo, on their stepping into RK, was that they were but his ‘arrangers’ from thereon – a job both were already adept at doing! ‘I have,’ said Raj Kapoor, ‘all the music I want on tape – for my coming films – already done by Shanker-Jaikishan. You two have, therefore, merely to carry out my imagery of how I want those SJ tunes audio-visually re-evoked!’ LP felt devastated when they heard this, but Lata urged the two to rough it out. ‘Remember,’ said Lata to LP, ‘all music at RK is traditionally given by Raj Saab himself, even SJ just carried out his command.’ Yet hear Lata’s Akhiyon ko rehne de – as ‘voiced over’ on Bobby Dimple – and you discern that LP did not supplant SJ, at RK, merely to be Raj Kapoor’s baton-wavers. LP’s Bobby come-through, in fact, signalled the legendary eclipse of Shanker at RK, even if, to the end, Shanker kept telling me: ‘I know Raj Saab will call me one day. How long, after all, could his stock of SJ tunes last?’

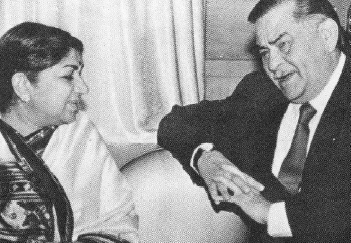

Mujhe kuchch kehnaa hai …Treat her like ‘royalty’ did Raj Kapoor as he discovered, with Bobby (1973), that he needed Lata, and Lata alone, to call the RK tune

Shanker-Jaikishan, ironically, had faded out, on Raj-Nargis as a pair, with Chori Chori, the musical that created a lifetime’s singing opportunity for Manna Dey. Whether it be Shanker’s Yeh raat bheegee bheegee or Jaikishan’s Aa jaa sanam madhur chaandnee mein hum, Manna Dey never sounded so fluidly romantic on Raj Kapoor – alongside a Lata silver-toned as ever on Nargis. The Binaca Geetmala competition, as Shanker then emphatically told Ameen Sayani, was euphoniously between his Yeh raat bheegee bheegee and Jaikishan’s Aa jaa sanam. Not so much between Shanker’s Jahaan main jaatee hoon and Jaikishan’s Panchchee banoon udtee phiroon. Yet Ameen Sayani played clear Binaca Geetmala favourites by according pride of ‘paaidaan’ place to Jaikishan’s Raag Pahadi-based Panchchee banoon udtee phiroon on Nargis, technically a duet in which Manna Dey, intriguingly, chipped in with just Gilloree (filmed on a rustic bit player)!

This set the tone for Shanker, ultimately, to challenge Ameen’s Binaca Geetmala credentials. No doubt Shanker’s new ground-breaking Jahaan main jaatee hoon, as compared to Jaikishan’s Panchchee banoon udtee phiroon, was the superior duet with its Czech-puppeteering folk motif. (Even if Shanker identified Jahaan main jaatee hoon as Punjabi folk!) Which lighter Chori Chori number do you prefer – Lata–Rafi’s Tum arabon ka her fer karne waale Ramji (on Bhagwan and Raja Sulochana), as tuned by Shanker, or Rafi’s All line clear all line clear (on Johnny Walker, Tun Tun & co.), as composed by Jaikishan? If you go for Jaikishan, then Chori Chori-plump, straightaway, for the younger partner’s Rasik balamaa, as it unveiled on Nargis. The senior Shanker, for his part, had Lata-Asha collaborating, jellingly, on Manbhaavan ke ghar jaaye goree, picturized on the instant Hindustani-hit Apalam chapalam pair of Sai-Subbulaxmi. Yet Shanker’s Manbhaavan ke ghar could not make quite the impact that C. Ramchandra had left, just seven months earlier on the electric-heeled Sai-Subbulaxmi, with Lata–Usha Mangeshkar’s Apalam chapalam and O baliye o baliye chal chaliye in Sriramulu Naidu’s Azaad (March 1955).

Laxmikant-Pyarelal entered the RK fold with Bobby as Raj Kapoor

told the duo they had merely to orchestrate his SJ tunes in stock.

Still, alongside Pyarelal, Laxmikant (being felicitated by Raj) stuck

it out for LP to create their own RK impact

For all that, C. Ramchandra’s Azaad (Meena Kumari-Dilip Kumar) had lost out to Hemant Kumar’s Nagin (Vyjayanthimala-Pradeep Kumar) in the matter of the 1955 Filmfare Best Music award. A prize, starting 1955 (unlike in 1953 and 1954), aptly turning into an award won for the full score of – not for just one song in – a film. In the year 1956, it was O. P. Nayyar’s C.I.D. (Shakila-Dev Anand) losing out to Shanker-Jaikishan’s Chori Chori, the film with which that highly innovative duo’s musical sway began. Or so we felt, until O. P. Nayyar came robustly roaring to lift the 1957 Filmfare Best Music award for heralding, via the good old Punjabi beat, a Naya Daur in Hindustani cinema.

Shanker was undoubtedly a hugely talented composer who, as he pinpointed to me, could play on the piano, accordion, sitar, dholak, daaph, pakhawaj, tabla and, of course, the harmonium. He once told me over a long evening that we spent together in his plush third-floor Backbay Reclamation apartment facing the sea: ‘Take our Main Nashe Men Hoon film’[1959: starring Raj Kapoor-Mala Sinha], ‘it’s me, Shanker, playing the harmonium, here, in Yeh na thhee hamaree qismat. Hear Usha Mangeshkar rendering Yeh na thhee hamaree qismat; has any composer made her sing a solo better? Take the accordion piece accompanying the Awaara hoon Mukesh solo on Raj Kapoor as Awaara,’ went on this master composer. ‘It was I, Shanker, who took the accordion from Goody Seervai’s hands and showed him exactly how – for how long – I wanted that piece played. No musician ever told me what to do. Ramnarain on the sarangi, Shivkumar Sharma on the santoor, Hariprasad Chaurasia on the baansuree, they all played precisely as I wanted to the nth length I needed. For instance, it was on the sitar, in the Kaanada ang, that I composed – for our [1959] film titled Kanhaiya – the Mukesh solo to go on Raj Saab singing about Nutan: Mujhe tum se kuchch bhee na chaahiye – as written-to-tune by the superfast Shailendra. It just went into Raag Darbari Kaanada on the sitar. That sitar of mine you see there has yielded me so many prize tunes. It was the most miserable day in my life, therefore, when my doctor advised me to stop playing on the sitar.’

‘My finger going on the sitar string,’ said my doctor, ‘could prove dangerous for a chronic diabetes patient like me. Well, that’s life, I suppose. There’s always the piano here to run my fingers over, if I can’t play the sitar there! I also remember how, when I was in a suit – like I am now – I played on a Western instrument like the piano. If I was in kurta-pyjama, I played on an Indian instrument like the sitar. Call me a simpleton but that’s the way I’m made.’ Clearly Shanker wore his composing heart on his baton-wielding sleeve. Any wonder O. P. Nayyar hailed Shanker as the real composer from among the two? (Wonder only why Naushad held the opposite view that Jaikishan was the more creative of the two?) ‘Even Shailendra,’ added Shanker, ‘I would let him write-only-to-tune. Writing the song first, I say, could lead to a certain monotony of metre. No, I do not agree that I cramped the poet’s style by insisting upon Shailendra’s writing-to-tune. Take Meraa jootaa hai Japani from [the 1955] Shree 420; take Sub kuchch seekhaa hum ne from [the 1959] Anari; take Jis desh men Ganga behti hai from the [1961] film of that name; take Sajan re jhoot mat bolo from [the 1966] Teesri Kasam – all four Mukesh solos of mine are Shailendra written and going on Raj Saab. Do you, anywhere in their unfolding, get the feeling that I have curbed Shailendra in his poetic flow? For me, the tune invariably came first. Even Ramaiyya vastavaiyya represent but words I put in as a naturalized Telugu.’ (Originally a Punjabi Raghuvanshi, Shanker had grown up in Hyderabad, taking root in that city to master the intricacies of the tabla. Side by side, as pioneering danseuse Hemavati and dance master Satyanarayan came to Hyderabad, Shanker wove his way into their troupe as a super tabla player, going on to tour with them. In such company, he was bound to acquire certain dancing skills himself – like, for instance, the finer points of Kathak. Shanker proceeded to train further under the highly exacting Krishnan Kutty. A nimble dancer himself, Shanker thus had the final say in the duo’s compositions attuned to go, say, with the steps assigned to a Padmini or a Vyjayanthi. In a Shree 420 number like Ramaiyya vastavaiyya, for instance – where there is a lot of dancing, led by the bubbly Sheila Vaz – Shanker’s terpsichorean artistry came into composing play. Shanker knew far more about dance than did Jaikishan.) ‘I tuned Ramaiyya vastavaiyya in everyman’s Bhairavi,’ as Shanker proceeded modestly to point out. ‘It was Raj Saab’s idea to ask Shailendra to retain my dummy Telugu words, Ramaiyya vastavaiyya, as the song’s punchline.’

Shanker was a marvel. He might have drawn away from his musical mentor, Raj Kapoor, following the entry of would-be playback singer Sharda into his otherwise drab later life. (‘She ensured that I had a home-cooked meal each evening, getting up very early to ready my afternoon lunch, for the day, according to my Andhra taste. All I wanted, when I returned home after a hard day’s work, was a wholesome Telugu style meal and she provided it for me on the dot.’) Raj Kapoor might or might not have considered this aspect of the Shanker–Sharda matter. But the tears in his eyes said it all – the pathfinder’s deep sense of regret at having lost all touch with a Shanker who (with Shailendra) had played such a clarion role in unfurling the RK banner. Unfurling the RK banner as something startlingly revolutionary in our cinesangeet at the turn of the half-century. Unfurling it as heralding ‘The Raj’ of Shanker-Jaikishan – all the way – from that turning point in Hindustani film music.

It was an immensely sad day, therefore, as Shanker suddenly died on 26 April 1987 (on a Sunday like Jaikishan). All the sadder since Raj Kapoor, as the creator of the Shanker-Jaikishan team, came to know of it only the day after. Even more overcome, therefore, felt Raj Kapoor about having had no use for RK’s yeoman, Shanker, after Kal Aaj Aur Kal (November 1971). This in the aftermath of Mera Naam Joker (early-1971) for which Shanker had conjured an unused 18-minute Awaara-matching dream sequence number. Like a man possessed did Shanker, on the piano, play that dream sequence number to me that evening. ‘Raj Saab has to send for me again, one day, for the Joker sequel in which this dream sequence would feature,’ insisted Shanker. From such a dream sequence did Shanker proceed, in the same ‘RK Bhairavi’, to play, masterfully on his drawing-room piano, the keynote Shailendra-penned, Mukesh-mooded 1964 Sangam solo, which this musician’s musician considered to be his best ever composition, unfolding as:

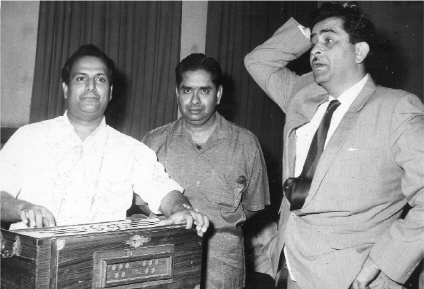

Hai aag hamaare seene mein … The RK Sextet (L to R): Raj Kapoor,

Shailendra, Jaikishan, Mukesh, Hasrat and Shanker

Dost dost na rahaa, pyaar pyaar na rahaa

Zindagee humein teraa aitbaar na rahaa,

Aitbaar na rahaa…

* In the credits, the music director was Ravindra Jain.