Rafi was the ‘complete singer’ in the real sense of the term. His vast oeuvre included classical music, romantic songs, sad songs, happy and peppy songs, patriotic songs, rock’-n’-roll and disco numbers, bhajans, shabads, qawwalis, naatiya kalaam and more!

Traumatized did Shanker-Jaikishan feel as, with the 1956 Filmfare Awards Nite almost upon them, Lata Mangeshkar refused to sing their Rasik balamaa at such a prestigious function. Thereby she also spurned the (5 May 1957) opportunity to put over the best song from Chori Chori, for Jaikishan, in the face of the glamour composer’s being set to be the neo-boy in Lata’s life. Chori Chori being Shanker-Jaikishan’ smaiden Filmfare Best Music award, the duo had reason to expect Lata to play ball, as their main lady singer right through the six years of their career– from Barsaat (1950) onwards. Where Lata took the entire media by surprise was in appearing to be sticking to her guns even after J. C. Jain, as the all-powerful general manager of The Times Group, had personally broached the matter with her. ‘Jain Saab,’ pleaded Lata, ‘how do you expect me to perform at a Filmfare function when there is no award still forthcoming for the Best Singer from your institution? Introduce such an award and see how I come and perform for you.’ In so couching her Rasik balamaa lament, Lata shrewdly ensured that the first ever Filmfare Best Singer award, if and when created, would come to her. Who could grudge Lata Mangeshkar such a Filmfare award if it turned out to be –as it did–for Salil Chowdhury’s Aa jaa re pardesee, so hauntingly picturized by master director Bimal Roy on Vyjayanthimala immortalizing Madhumati?

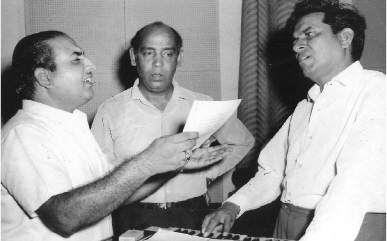

Na jhatko zulf se paanee … Mohammed Rafi, Rajendra Krishna and Ravi

The 1958 Filmfare Best Playback Singer award went to Lata when Mohammed Rafi was already matching her as No. 1. Rafi never worked towards an award; it came to him on sheer performing merit. Yet there could be no doubt that the style of stand Lata adopted did delay, maybe unwittingly, the Filmfare Best Singer award to Rafi by a year at least. For by 1959 Mukesh emphatically signalled his playback comeback by clinching the Filmfare Best Singer award on who, if not Raj Kapoor, through Shanker’s Sab kuchch seekha hum ne, crafted, in straight-line collaboration with Shailendra, for Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Anari. This genial singer’s stock rose skyhigh in the industry as he collected the coveted statuette from the hands of chief guest Gamal Abdel Nasser, president of the United Arab Republic. Second to Mukesh on that 1959 awards list was a performer who had been commanding, by 1950, the same Rs 500 per-song fee as Lata Mangeshkar then got –the one-andonly Talat Mahmood, crooning Jalte hain jis ke liye on Sunil Dutt playing Adheer opposite Nutan as Sujata in the 1959 Bimal Roy film. Composer S. D. Burman had wanted Jalte hain jis ke liye to be in the voice of Rafi, but director Bimal Roy intervened insisting that the song, so feelingly written by Majrooh Sultanpuri, would work only in the sentimentally soft voice of Talat Mahmood. Talat, having vocally made a strong case for a Best Singer Filmfare award in the year 1954 (through Jaayein toh jaayein kahan in Taxi Driver), took his 1959 setback well, arguing that he would have rather lost the trophy to his dear friend Mukesh than to anyone else.

Inherent in this compliment was the rueful admission that both Talat and Mukesh had struggled hard, very hard, through five years in an effort to regain their lost niches as top singers in Hindustani cinema. Both had come up against an indomitable hurdler in the robustly delivering Rafi –put on his vocal mettle with Lata’s emerging as the first to win the Filmfare Best Singer award. Lata and her Mukesh bhaiya clinching the award in successive years (1958 and 1959) only sharpened the competitive edge in Rafi.

Thus did Rafi come with a bang, winning 4 of his 6 Filmfare awards when there was only one such prize for the male and female singer put together. It was the quietly-at-it Ravi who fetched Rafi his first Filmfare Best Playback Singer award, in 1960, for our tuneful titan’s Raag Pahadi rendition of the Shakeel Badayuni-penned Chaudhwin ka chand ho ya aftaab ho. An evergreen filmed on Guru Dutt and, therefore, eminently predictably, sung in praise of Waheeda Rehman –as that aesthete’s Chaudhwin Ka Chand now and forever. Having lost out on this prestigious award in its first two years, Rafi claimed it yet again in 1961. This time it was for his singular flair in vocalizing Jaikishan’s Teree pyaaree pyaaree soorat ko, the Hasrat Jaipuri-envisioned Sasural number witnessing ‘Box Officer’ Rajendra Kumar extolling the kamalnayanee beauty of Byrappa Saroja Devi, in choice chashme-e-bad door terminology. Like in the case of Chaudhwin ka chand ho, it was Raag Pahadi that did the Best Singer trick, anew, for Rafi in 1964, as his soulful rendition of Chaahunga main tujhe saanjh savere (on Sushil Kumar) proved crucial in freshers Laxmikant-Pyarelal’s lifting their first Filmfare Best Music award for Rajshri’s Dosti. This from under the nifty nose of Messrs Shanker-Jaikishan, the old firm feeling scandalized at coming off next best when the duo’s Filmfare challenge, in 1964, had come to be mounted in the glossily romancing Raj Kapoor–Vyjayanthimala mould of RK and its Sangam, the film embodying Rajendra Kumar’s Yeh meraa prempatra padh kar in the masterful voice of Rafi.

Tasveer banaata hoon teree…

Naushad-Rafi

Jaikishan is eminently remembered for the silken-smooth vein in which he got Mohammed Rafi to go on the same Rajendra Kumar in Bahaaron phool barsaao. This Suraj soother, Hasrat-penned, came wafting through in Raag Shivranjani and fittingly therefore sealed the 1966 Filmfare Best Singer award for Rafi. Even if, equally, this award to Rafi could have been for S. D. Burman’s Kyaa se kyaa ho gayaa on Dev Anand in Guide. But the music part of Filmfare Awards had become a package deal by this 1966 stage. That is to say, if Shanker-Jaikishan bagged the Best Music statuette for Suraj, Rafi automatically stood to benefit (from the same Filmfare coupon entry) as the Best Singer. Thousands of Filmfare copies (sans the entry coupons) dumped by Bombay’s Haji Ali seaside –during the year-end –became a familiar phenomenon in the matter of invoking the ‘awarding’ blessings of the Holy One there. With all that said, who can deny that Rafi’s rendition of Jaikishan’s Bahaaron phool barsaao was so toned on Rajendra Kumar as to merit Best Singer attention independent of any such external agency aid? Rafi had vocally peaked in the face of every effort by Her Majesty’s Opposition to check his advance.

At this point occurred the bifurcation of the playback award into Best Male Singer and Best Female Singer. Come 1968 and Rafi won it as Best Playback Singer again, not for Jaikishan’s Hasrat-penned Brahmachari number, Dil ke jharokhe mein tujh ko bithaa kar –as recurringly wrongly published, year after year since, in Filmfare itself – but, for Shanker’s Shailendra-written two-way Brahmachari solo (on the otherwise boisterous Shammi Kapoor), going so serenely as Main gaaon tum so jaao. The Sixteenth Annual Filmfare Awards official presentation booklet confirms this on Page 14: The ‘Main gaoon tum so jao’song (actually ‘songs’: there are two versions) in “Brahmachari” has fetched for Mohammed Rafi his fifth “Filmfare”trophy.’ Also, the (28 March 1969) Filmfare awards’ announcement page carries, in bold lettering, the entire 1968 official awards’ listing in the form of Winners of The Sixteenth Annual Filmfare Awards, including:

Best Playback Singer (Male): MOHAMMED RAFI–Brahmachari (Main gaoon tum so jaao)

Rafi’s sixth and last such award, following an unprecedented career crisis, was to manifest itself only nine years later in 1977–fulfillingly, for Kyaa huaa teraa waadaa, co-sung with Sushma Shreshtha as tuned by Rafi’s bogey boy, R. D. Burman, in Hum Kisise Kam Naheen. Here at last was a Nasir Husain film in which Rafi’s straight vocal competition was with Kishore (four songs to each). This, as a Filmfare prize bagged at the crest of the Kishore–RD wave, made Rafi feel mentally stimulated –to discover that he could land such a precious award even under the Pancham baton.

How do you truly test a stalwart singer’s longevity? I do it, in Mohammed Rafi’s instance, by having for my touchstone the singer’s rare ability to leave his imprint even in the one solo he has going in any film. I get such a rare solo in Rafi’s case even where the composer is a personality for whom the singer’s renditions are legion. I mean Rafi under the baton of Naushad. This Naushad–Rafi phenomenon begins as early as 1946 with Anmol Ghadi, the Noorjehan–Surendra golden jubilee hit musically dominated by those two singing-stars alongside a still emerging Suraiya. Yet, in his first ever playback solo for Naushad here, is not Rafi recalled, to this day, in a crystal-clear tone of Teraa khilauna toota baalak teraa khilauna toota? Take Mela, the Nargis–Dilip Kumar 1948 golden jubilee hit the matized by Shamshad Begum and Mukesh in dulcet tones of Dhartee ko aakash pukaare. Actually, in Mela, Rafi is heard but once –on one Rafeeq Arbi! Yet how Naushad has Rafi Raag Bhairavi-impacting –literally through the film’s credit titles –as Yeh zindagee ke mele yeh zindagee ke mele. Next, in A. R. Kardar’s 1952 Suraiya– Suresh starrer, Diwana, for example, Naushad attempts the near impossible. By venturing to replicate, from Dulari (1949), his Raag Pahadi Rafi mood-setter: Suhaneee raat dhal chukee (going on Suresh). Imagine, on the same Suresh, next in Diwana (1952), Naushad succeeds spectacularly –via a Rafi coming through as Tasveer banaata hoon teree khoon-e-jigar se. How this Rafi–Naushad master piece vied with the same singer-composer duo’s Suhanee raat dhal chukee for Radio Ceylon attention. By which I mean that there were imaginative announcers like Gopal Sharma who created Radio Ceylon opportunities for usto compare and contrast Rafi & Rafi on ‘Suresh & Suresh’!

Yet Rafi’s real vocal scrutiny was in Mehboob’s Amar, a show eminently euphoniously dominated by Lata–on Nimmi and Madhubala alike. A show where you just could not Raag Yaman-choose between Lata’s Na miltaa gham (on Nimmi) and her Jaane waale se (on Madhubala). In fact, Amar finds Lata to be (for a young lady who was far from well throughout the film’s recordings) remarkably elastic of voice –to the end. Elastic of voice via Naushad’s patent Raag Bhairavi – via the two-sided 78-rpm (N51065) record projecting Lata in persuasive tones of Khamosh hai khewanhaar meraa, so tellingly audio-visualized on Nimmi. Yet Rafi, too, has a strikingly similar two-sided 78-rpm Raag Bhairavi presence in Amar –through Insaaf ka mandir hai (N51064). True, Insaaf ka mandir hai is simply ‘voiced over’ (in snatches) on Dilip Kumar. But to what after-effect!

Let us leap-frog to 1974–to My Friend. As Lata here had 3 Naushad numbers, all to herself, Rafi flaunted but one solo –on one Rajeev opposite Prema Narayan. Yet that Raag Bhairavi solo became a hallmark number. Recorded as it was, by Naushad, to revive Rafi’s vocal self-belief in the face of the Kishore Kumar onslaught. The My Friend Rafi solo, coming over as Naiyaa meree chaltee jaaye, is by no means Naushad at his Bhairavi best. Still it is a highly timely 1974 rendition by Rafi, seeing how it recharged that Singing Atlas into mounting a fresh offensive on Kishore Kumar, as Naushad thoughtfully ensured that this dedicated performer also received the Rs 15,000 fee he had charged for a song before Aradhana (end-September 1969). From hereon, if Kishore admitted no match, Rafi brooked real watch. You should have seen Rafi walking down the aisle to ascend the stage when his name was announced as the 1975 Film World Best Singer for Usha Khanna’s Sawan Kumar-written Teree galiyon mein na rakhenge qadam aaj ke baad on Anil Dhavan in the 1974 film Hawas. You could see the thrill Rafi was feeling at clutching, in his uplifted right hand, a Best Singer award after so many years. Manna Dey summed it up neatly in his Memories Come Alive – An Autobiography:*

When I made my first foray into Mumbai’s film industry, Mohammed Rafi was its blue-eyed boy. His songs touched people’s hearts. With Kishore Kumar’s arrival on the scene, however, Rafi gradually started losing ground. With their pulse on what the audience wanted, most producers clamoured for Kishore. Rafi was naturally quite disheartened by the way he had been sidelined from his once-prominent position. Had Rafi come to terms with the capricious ways of a transient world and decided to be content with the public adulation he had once enjoyed, he would not, perhaps, have suffered quite so much over his rejection and ended up so bitter over the whole affair.

Bitter to such a point–according to his mentor Naushad–did Rafi become about the Kishore Kumar factor that it even resulted in this ultra-seasoned singer’s momentarily losing poise in the recording studio. Naushad said he had heard about such a shattering development but wanted to find out things for himself. To this end, Naushad, without his disciple Rafi’s knowledge, slipped into Mehboob Studios at a point when a recording by his favourite singer was in progress. Naushad said he felt stunned at viewing some ‘tuppenny-hapenny’ people, inside the studio, making bold to tell Rafi about how to perform to match Kishore Kumar if he hoped to get back. Naushad just got up and walked away, discreetly leaving a message for Rafi to call. As Rafi arrived, Naushad said he first made his laadla performer feel at ease in his music room, reminding him of the numberless song rehearsals the two had done in that memorable setting. As Rafi thus moved into a more positive frame of mind, Naushad candidly told him: ‘Who is this Kishore Kumar? Does he have command over evena fraction of the classical repertoire that you, Mohammed Rafi, possess as a singer? In any case, who are those nonentities, in the recording studio, to tell the mighty Mohammed Rafi how to sing or how to match a grammarless performer like Kishore Kumar? You are not Kishore Kumar, Rafi,’ bore in Naushad, ‘you are Mohammed Rafi and only Mohammed Rafi –an idol who overtook all other male playback singers in the film industry to emerge as Bharat’s Number One. When so many well-trained singing rivals never succeeded in giving you a complex, how could you, possibly, get self-conscious about the so-called singing prowess of a Kishore Kumar? Come out of it and be your own singing self, Rafi. Even today, there is not a male singer to touch you. Least of all Kishore Kumar whose classical background is nil.’

Naushad’s pep talk, if sounding far from fair to Kishore Kumar, did wonders for Rafi’s morale. It galvanized this adaakaar’s adaakaar into venturing to begin his journey back, shaking off all those cobwebs of Kishorean confusion that might have clouded his vocal judgement. Naushad was always dismissive of Kishore Kumar as a singer. But was Kishore Kumar’s meteoric rise with Aradhana all that fortuitous? By no means, as Manna Dey has underscored. In such a Naushad-contemptuous context, let us take a fresh look at Rafi and his Aradhana.

Let us never forget that even that megastar of megastars, Amitabh Bachchan, could not arrive with the bang the way Rajesh Khanna did via Kishore Kumar with Aradhana (by end-September 1969). Kishore’s getting to be so Aradhana-rivetingly viewed on Rajesh Khanna did, let us face facts, culminate in Rafi’s progressively shedding his vocal charisma on Rajendra Kumar, Shammi Kapoor and Sunil Dutt, Dharmendra, Jeetendra and Shashi Kapoor. Even the Rafi-settled Dilip Kumar, at one stage, felt impelled to turn to Kishore Kumar–with Saalaa main to saahab ban gayaa in S. D. Burman’s Sagina (1974). Dev Anand alone, having discovered the secret of all-time youth, remained vocally untouched by the Rajesh–Kishore wave.

How did Kishore Kumar Aradhana happen to Rajesh Khanna? An actor prematurely hailed by publicist K. Razdan (in the 1967 Raaz) as ‘Super Star’ Rajesh Khanna. (As ‘Super Star’ Rajesh Khanna starring opposite ‘Kiss Girl’ Babita.) Aradhana’s release-eve saw the boxing-glove tight-fisted S. D. Burman throwing a music-unfolding party. A party at his posh Khar-Bandra located ‘The Jet’ home. A party witnessing son R. D. Burman –the one all set to work wonders via Kishore Kumar on Rajesh Khanna –being pushed into ‘The Jet’ corner. No one, just no one, seemed to care to notice RD that evening. They had ears only for Papa Burman. Ears in terms of how Aradhana’s music had come to be made. In terms of how Roop teraa mastaana and Mere sapnon kee raanee had taken shape on Rajesh Khanna. In terms of how Koraa kaagaz thhaa yeh man meraa had come to be attuned to go on Rajesh Khanna opposite Glam Puss Sharmila Tagore. Dada Burman that evening discreetly avoided all mention of those two Aradhana duets, Asha–Rafi’s Gungunaa rahein hain bhanwre (set to go on Sharmila-Rajesh) and Lata–Rafi’s Baaghon mein bahaar hai (to go on Farida Jalal-Rajesh Khanna), though those two numbers were the first ones to be recorded (by a still-well SD himself) for the film! Rafi, in fact, stood already Dada Burman-earpicked, as Rajesh Khanna’s voice, in that Shakti Samanta ‘meta morphoser’ styled Aradhana. Unfortunately, Dada Burman fell seriously ill after recording the above two duets. Meanwhile, Rajesh Khanna was also shooting, opposite Asha Parekh –for the same Shakti Samanta–Kati Patang, the cult film for which the son, Pancham, was writing the musical score.

That Rajesh Khanna was also Pancham’s personal friend gave RD the scope to go the whole Kishore-hog in Kati Patang (1970). The results were amazing as Pancham recorded the three solos to go on Rajesh Khanna as Yeh shaam mastaanee, Pyaar deewaana hotaa hai and Yeh jo mohabbat hai. This, haplessly for Rafi, was the hazardous hour in which S. D. Burman’s condition worsened and an already busy RD–as Dada’s chief assistant still on Aradhana –had, willy-nilly, to take over that Rajesh–Sharmila starrer’s music at the instance of Shakti Samanta. That is how Rafi, never a Pancham pet, historically lost out to Kishore Kumar. Pancham had told me even earlier that, given half an opening, he would plump for Kishore Kumar at the expense of Rafi.

S. D. Burman, initially, was not pleased about such a development, keeping in mind the wonders Rafi had done for his career. Though there were vocal sickbed arguments between the father and the son on this topic, Dada Burman was too ill really to protest. Next, success rationalized it all, as Rajesh Khanna hit the screen like an avalanche with Aradhana. Tellingly thus –once back on his feet –did S. D. Burman seize the Aradhana baton back from son RD with ‘The Jet’ party. Against such a backdrop, Pancham’s leaving S. D. Burman was clearly a matter of time. In the Aradhana aftermath, I well knew that, if Pancham fulfilled his potential to emerge as the new-waver without peer, Rafi would be the first casualty.

Since Dada Burman played such a key role in Rafi’s Dev Anand advance, it might be worth examining how this superstar-spangled singer, after becoming such a fixation as the voice of Dilip Kumar, made the debonair Dev Anand transition under the resourceful baton of S. D. Burman. Keeping in mind that, in the 1947–56 decade, Rafi was not heard in a single SD number going on Dev Anand, it was a rare moment for Rafi when he was, at long last, summoned by this ‘vintageing’ composer to sing for the dashing Dev Anand. Hence, Rafi made the long-overdue 1957 Dev–S Dentry with those cute Asha-pairing Nau Do Gyarah duets: Kalee ke roop mein chalee ho dhoop mein kahaan and Aa jaa panchchee akelaa hai (two numbers recorded in that order by Goldie-SD). Actually, it was on the Nau Do Gyarah-debuting Goldie Vijay Anand’s urging that Dada Burman finally turned to Rafi on Dev Anand, following certain doubts about cent per cent cooperation forthcoming from his favourite singer Kishore. This despite the otherwise fabulous Nau Do Gyarah recording of Kishore–Asha’s Aankhon mein kyaa jee.

My Rafi theme song however is, not the SD duet, but the Dada solo on Dev Anand in the vibrant voice of this supremely versatile singer. What better Rafi first choice, here, than the 1958 Kala Pani classic on Dev Anand: Hum bekhudee mein … a tune Dada Burman ingeniously adapted from the muezzin’s call to prayer. A call going as: Aal-e-rasool mein jo musallama ho gaye. S. D. Burman turned Aal-e-rasool mein into a Bengali song in his own voice, testing it out on the Calcutta audience, before bringing it to Bombay for Majrooh to ‘write to tune’ as Hum bekhudee mein tum ko pukaare chale gaye!

If far-and-away Binaca Top –in the 1958 film Solva Saal, on Dev Anand, under S. D. Burman –was Hemant Kumar’s Hai apnaa dil toh awaara, there is also no wishing away Rafi’s Yeh hee toh hai woh in the same movie. As Bambai Ka Babu, it is by Rafi’s peerlessly poignant Saathee na koee manzil that we picture Dev to be in the talismanic custody of SD. How, with the aim of baiting Kishore Kumar, SD brought in Rafi and Hemant Kumar, by tantalizing turns, on Dev Anand! Maybe the SD– Dev signature tune, in Baat Ek Raat Ki next, is Hemant’s Na tum humein jaano. Yet is Rafi, in the same 1962 film, not identifiably Rafi, under Dada on Dev, via Akelaa hoon main? Navketan’s Kala Bazar (1960) had seen Dada Burman, tellingly individualistically, plumping wholesale for Rafi on Dev Anand. How heart-stoppingly did SD, in that Goldie movie, have Rafi switching moods on Dev Anand –from Apnee toh har aah ek toofan hai to Khoya khoya chaandkhulaa aasmaan! SD did that after having established Rafi as his neo-voice on Dev Anand, in the same film, with Teree dhoom har kahein tujhsa yaar koee nahein.

Yeh naadaanon kee duniyaa hain yeh deewanon kee mehfil hai …Rafi on song

Goldie Vijay Anand had much to do with fixing Rafi, on Dev Anand, in Kala Bazar (1960) as in Tere Ghar Ke Saamne, coming in 1963. In Tere Ghar Ke Saamne, does not the Dada–Rafi–Dev threesome make things fairly hum with Dil ka bhanwar kare pukaar and Tu kahaan yeh bataa? Remember how the picturization of Tu kahaan yeh bataa (the Rafi-on-Dev solo) carried a near Shangri-La look inside a studio-created Shimla! Yet my pet here is Sun le tuu dil kee sadaa for the sheer Raag Bhairavi aptitude with which S D has Rafi performing on Dev. The 1965 Teen Deviyan had, not its director (in the credit titles), Navketan publicist Amarjeet, but Goldie Vijay Anand anonymously doing all the song-taking. Hence the ladies-swooning spell cast via Dev Anand, by Rafi-SD, with Kahein bekhayaal ho kar, so engagingly written by Majrooh. Yet is not the Raag Gaara-tinged Aese toh na dekho (projecting a Nanda whom Goldie then fancied as his bride in real life!) a matching Dada Burman– Rafi Teen Deviyan standout on Dev Anand? Again, it is in the Raag Gaara gear that Goldie has Rafi wrapping Tere mere sapnen ab ek rang hai – come Guide. Indeed, as Dada told me, Goldie and he could not have brought off Guide (1965), as a film, sans the virtuoso vocals of Rafi to articulate, first, Din dhal jaaye haaye, then Kyaa se kyaa ho gayaa.

In this context, how do we interpret the sustained anti-Rafi stance of two such new ground-breakers of their time as C. Ramchandra and R. D. Burman? Especially when it is on record that first C. Ramchandra, then RD, used Rafi crucially to further their early careers? Rafi and Lata rate, in my 60-year-plus musical esteem, as the two best-ever playback performers in Hindustani cinema. In fact, repeatedly did I dispute, with both C. Ramchandra and R. D. Burman, their arbitrary downscaling of Rafi, simply because he took a bit of readying for a recording, when it is the composer’s set job to be patient with a singer to be able to draw out the exact vocal nuancing he wants from the performer. Was our spectrum of vintage composers’ experience any different, in preparing, say, Mukesh for a take? Or in rehearsing Ghazal King Talat Mahmood where it came to controlling the tremolo in his voice? Unlike Pancham, S. D. Burman thought the world of Rafi for the extensive Akelaa hoon main spadework that this disciplined singer did before presenting himself at the 1962 Baat Ek Raat Ki recording. The picture, incidentally, was no different with the ‘Mohammed Rafi of the South’, T. M. Soundararajan, who was ready for a take only after meticulously preparing for a Viswana than– Ramamurthy recording. Shanker-Jaikishan and O. P. Nayyar were among our busiest music makers through the 1957–66 decade. Yet neither had any problems giving Rafi the mental space he needed before a take. Could Rafi possibly have commanded a 36-year career-record of 4856 film and non-film songs –by far the highest among male performers –without having studiously met every dimension of demand by every genre of composer?

Once at a recording, the years junior Usha Khanna (who tuned his Hum jab chalen toh yeh jahaan jhoomein in Hum Hindustani, 1960) told Rafi that she just had not been able to summon the gumption to direct him about a murki she wanted taken differently. ‘But why didn’t you insist?’ chided Rafi. ‘Remember, as the music director, you have the right to order me!’ Indeed, Rafi shaper Naushad validly sought to know why any true music maker would want a change of tune after having fully rehearsed the singer for the take. ‘First, I have to be totally formatted in my composing,’ a sserted Naushad. ‘When I envision, say, Ae husn zaraa jaag in Raag Yaman, I already have the [1963] Sadhana–Rajendra Kumar Mere Mehboob mood picture before my eyes. Only after I am audio-visually ready with the tune do I call in Rafi for the take, knowing I would be getting nothing less than one hundred per cent from the man this way. I recall rehearsing Rafi for Aaye na baalam waadaa kar ke in Raag Gaud Sarang going on Bharat Bhooshan playing the singer-hero in Shabab [1954]. After I so rehearsed him, Rafi knew that there would not be any change of tune. The composer seeking a change of tune, after rehearsing the singer, is no composer at all. If the mauseeqaar does not know his own mind,’ concluded Naushad, ‘how does he interact with a “total composer-follower”like Rafi? Remember, once you played [to go on Dilip Kumar in Dil Diya Dard Liya, 1966] something like Koee saaghar dil ko behlaata nahein in Raag Kalavati to Rafi, it got imprinted in his mind–Bas chhap gayaa samajhye.’

Would Rafi, as noted by S. D. Burman, have rendered Jalte hain jis ke liye (in Sujata, 1959) as surpassingly as did Talat Mahmood on Sunil Dutt? That is like asking if Talat would have crooned Apnee toh har aah ek toofan hai as sensitively as did Rafi on Dev Anand in Kala Bazar (1960). ‘Talat’s no good as a singer, Mukesh is worse!’ Dada Burman emphatically told me. To each his own, though the generally soft-spoken Dada Burman’s using such harsh language about any top singer came as a surprise to me. In any case, by that 1960 stage, Rafi was S. D. Burman’s first male choice. Yet not even 10 SD songs accrued to Rafi during Dada’s first 10 composing years in Bombay (1946–55)!

How? Rafi’s first for Dada Burman was the Duniyaa mein meree aaj andheraa hee andheraa solo in Do Bhai (1947). Then Dada forgot all about Rafi for four long years, until the Ek Nazar duet with Lata: Mujhe preet nagariyaa jaana hai. Followed, in 1951 itself, two Geeta–Rafi offerings by S. D. Burman: Panghat pe dekho aayee milan kee belaa and Zaraa jhoom le jawanee ka zamaana hai suhaana. Strangely, neither number came to stand out in A. R. Kardar’s Naujawan (1951). So it took Rafi a further two years, vis-à-vis SD, to come through with Mahesh Kaul’s Jeewan Jyoti. This happened with Geeta–Rafi’s 1953 Radio Ceylon hit, O lag gayee akhiyaan, set in Raag Multani to go on debutante Chand Usmani pairing with struggler Shammi Kapoor. Still Dada Burman remained unimpressed by Rafi, until Bimal Roy’s Devdas released in the first week of January 1956.

Rafi’s spot comparison in Devdas was with a Talat Mahmood ever so ‘moodily’ soliloquizing Laagee re yeh kaisee anbuj aag and Kis ko khabar thhee kis ko yakeen thhaa on Dilip Kumar playing the title role. Devdas happened just two weeks after Rafi’s having yet again failed, somehow, to score, for Dada Burman, in Shahid Latif’s Society –neither Geeta– Rafi’s Raham kabhee toh farmaao nor Rafi–S. Balbir’s Ab aa bhee jaa kee teraa intezaar kabh se hai created an impact. Still, 14 months later in Pyaasa, it inevitably had to be Rafi resonating Sahir Ludhianvi’s quality poetry for S. D. Burman. Not even the Sahir effect left by Hemant Kumar’s Jaane woh kaise log thhe jin ke pyaar ko pyaar milaa (on a Guru Dutt being suspiciously scrutinized by Rehman) diminished Rafi’s virtuosity in Pyaasa. In fact–like on Dev Anand in Guide eight years later–Rafi alone could have brought off those two Sahir classics: Yeh kooche yeh neelamghar dilkashee ke and Yeh mahalon yeh takhton yeh taajon kee duniyaa, on a Guru Dutt not really making you miss Dilip Kumar in a role originally designed for that thespian. SD, in Pyaasa, got a genuine feel of Rafi’s tonal dimension as this multihued performer moved tellingly from Hum aap kee aankhon mein on Guru Dutt (O. P. Nayyarized with Geeta Dutt going on Mala Sinha), to Sar jo teraa chakraaye (on Johnny Walker), to Jinhen naaz hai Hind pe woh kahaan hai and Yeh duniyaa agar mil bhee jaaye toh kyaa hai (both on Guru Dutt). Following such a peaking, the Rafi–SDteam’s Miss India introduction to naya paisa via Badlaa zamaana waah waah badlaa zamaana sounded a great Binaca Geetmala letdown. Yet this 1957 year was the Pyaasa one with which, after a decade’s hesitancy, S. D. Burman did settle for Rafi even on Dev Anand –with Navketan’s Nau Do Gyarah. After Hum bekhudee mein (in Kala Pani, 1958) and Khoya khoya chaand (in Kala Bazar, 1960) happened on Dev Anand, Rafi always was compulsive competition to Kishore Kumar in Dada Burman’s composing imagination.

Rafi would, almost certainly, have remained that scale of S. D. Burman-baton competition to Kishore, if only Dada Burman had not, inexplicably, moved away from this composer’s performer. Moved away after being supremely happy with Meraa man teraa pyaasa, as the first song he recorded for the film –by way of a Rafi solo –to go on Dev Anand playing Gambler (1971). As Rafi reached SD’s Khar-Bandra bungalow for a final rehearsal, SD told Rafi that he knew how well prepared he always came. Thereupon Rafi suggested that SD and he travel in his car to Mahalaxmi’s Famous Labs for the recording. But Dada Burman vetoed the idea and said the two would go in his Fiat car. Dada Burman wanted one final inside-car rehearsal with Rafi but not in Rafi’s limousine. This was to obviate the possibility of Rafi’s own driver’s getting to view the composer as correcting the singer –his employer. The rehearsal in the Fiat car went so smoothly that S. D. Burman okayed the very first Meraa man teraa pyaasa take.

Pray, what then was wrong with Rafi’s solo rendition for Dada Burman to have switched back –in the same Gambler wholesale –to Kishore Kumar for Dil aaj shayar hai and Haan – kaisaa hai mere dil tuu khiladee on a Dev still looking beautiful rather than handsome? Not to speak of those two Kishore–Lata Gambler duets for which too, strangely, Rafi was out of consideration–for Choodee nahein yeh ramera dil hai and O-o-o apne hoton kee bansee banaa le mujhe. At least on the 1969 issue of Gungunaa rahein hain bhanwre and Baaghon mein bahaar hai in Aradhana, the Kishore switch could be interpreted as Pancham’s arbitrary decision. In the 1971 Gambler, however, was it SD’s own conscious judgement that had him shying away from Rafi? Why such double think? Maybe, just maybe, because Kishore Kumar –as Dada Burman’s own original discovery (made earlier than all other composers in terms of potential) –was clearly the ‘on’ voice following the end-September 1969 Aradhana backlash. A Rafi-sweeping backlash that even S. D. Burman could not totally ignore as one who –all things being equal –was never one to disturb the settled order. Conclusion –when an Aradhana happens, it happens. The wave of youthful enthusiasm generated, in such an extraordinary situation, is such that it takes, in its parabolic curve, even a singer of Rafi’s timbre and calibre. Our tonal titan’s after-Aradhana plight is succinctly summed up, in the form of a near elegy (created by the Kaifi Azmi–S. D. Burman combo) to vivify the stunning 1959 Kaagaz Ke Phool climax on Guru Dutt –a climax Rafi-unfolding as:

Dekhee zamaane kee yaaree

Bichhde sabhi, bichhde sabhi, baaree baaree

Arre dekhee zamaane kee yaaree

Bichhde sabhi baaree baaree

Kyaa le ke miley ab duniyaa se

Aansoo ke sivaa kuchch paas nahein

Ya phool hee phool thhe daaman mein

Ya kaaton kee bhee aas nahein

Matlab kee duniyaa hai saaree

Bichhde sabhi, bichhde sabhi, baaree baaree…

* Penguin, New Delhi, 2007, p. 195.