Down the years…did Lata rule, untouched. Any threat that Suman Kalyanpur, Vani Jairam, Sulakshana Pandit, Hemlata and Anuradha Paudwal – all genuinely talented – later mounted remained transient in the grand sum. Madan Mohan said it all when he emphatically stated: ‘We music directors, as a Metro–Murphy team, went all over India, end-1956, only to discover there is no one even remotely as good as Lata. It is our great good fortune that Lata happened in our time.’

The first five spots on the music charts belonged, exclusively, to Lata Mangeshkar within a year of her major career-building conquest–in the Naushadian idiom of Andaz. This Dilip Kumar–Nargis–Raj Kapoor starrer (released on 21 March 1949 at the showplace of the nation, Bombay’s Liberty Cinema) marked a path-breaking Lata advance made at the expense of the well-entrenched Shamshad Begum, heroine Radha’s bell-clear voice in Nargis–Dilip Kumar–Naushad’s 1948 golden jubilee hit: Mela. However, Lata’s singing –as belatedly admitted by her on her 80th birthday (28 September 2009) –received its real career-boosting (RK) impetus only with the advent of Nargis–Raj Kapoor’s Barsaat (released at Imperial Cinema, in Bombay, on 10 March 1950). In thus bringing herself to acknowledge the gale force that was Barsaat in her singing life, it was for the first time that we had Lata moving away from Mahal, Madhubala and Aayegaa aayegaa aayegaa as her pet obsession. In fact, Mahal released a good seven months later (on 13 October 1950) at Bombay’s Roxy Cinema –following Kamal Amrohi’s Bombay Talkies film being caught up in endless litigation. Lata by then had become the prima donna set to finish as the doyenne of singers that she is today.

Indeed, by the Mahal turn of the half-century, Geeta Roy alone stood up as still offering Lata genuine competition, as Shamshad Begum, Zohrabai Ambalawali, Parul Ghose, Rajkumari and Amirbai Karnataki, overa period of two years (1951–52), just faded away.

If Madhubala and Mahal are synonymous, so are Lata Mangeshkar and Aayegaa aayegaa aayegaa. This Madhubala-beckoning solo proved our 21-year-old fledgling’s radio cut-through number –as a Nakshab song-lyric none too confidently tuned by a Khemchand Prakash feeling he was beginning to lose ground. Also, Aayegaa aayegaa aayegaa happened to Lata at a time (end-1950) when film music stood all but banned on All India Radio and there was no Radio Ceylon either. It was therefore from Radio Goa (which was then under Portuguese occupation, coming to be liberated in December 1961 by India) that we first heard Lata sounding hauntingly beautiful on Madhubala. Her vocal timbre was such that it had all those ‘open’ voices, led by Shamshad Begum, sounding suddenly dated. Where Asha took her own time to evolve, where many others came on fast and faded away even faster, Lata stayed on to become the singing icon of the nation –her imprimatur, as the First Lady of Hindustani Film Music, secure as ever. Such is the quality of Lata’s oeuvre in her melismatic prime that long after the Pradeep written, C. Ramchandra-tuned Ae mere watan ke logon occurred (end-January 1963) did this ‘performer’s performer’ remain the ‘Aceof Spades’ in the playback pack. As formidable as the Ace of Spades she still is. Even if Lata today, sadly, gives the lie to Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan’s dictum: ‘Kambakht, kabhee besuree hee nahein hotee!’ (Damn it, she never goes out of tune!). Shanker-Jaikishan’s Manmohana bade jhoote (Raag Jaijaiwanti) was Lata on a saree-toned Nutan symbolic of Seema by December 1955. Baiyaan na dharon o balmaa (in Raag Charukeshi) unveiled, by January 1971, as Lata–Madan Mohan’s ‘all-timer’ on an image-switchingly turned-out Rehana Sultan in Dastak. Could one possibly envision such a Lata–Madan Mohan Dastak classic as Baiyaan na dharon o balmaa losing out, in the Sur-Singar Best Classical Film Song of the Year contest, to fledgling Vani Jairam’s Bole re papihara? To a Vani going on Jaya Bhaduri debuting as Guddi in the September 1971-released Hrishikesh Mukherjee film of that name?

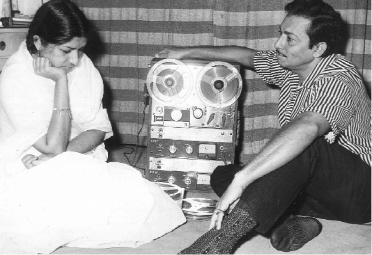

Jaana thhaa hum se door … the Adalat in which we judge Lata-Madan

Yet the Sur-Singar Committee’s vote, as decisively as 4–1, was for Vani’s Raag Mian Ki Malhar rainbow chaser, Bole re papihara, composed by the ageless Vasant Desai. A number readily appealing to four of the five judges on the strength of the fact that it had already earned Vani a Special Mention in the 1971 Filmfare Awards’ listing, a citation seeing her zooming in as the new singing sensation –given a climate audibly lacking vocal variety. The Sur-Singar voting was at Podar House on the Marine Drive ocean front. Believe it or not, Snehlata Podar alone–from among the five judges during the actual voting –was for Lata–Madan Mohan’s Baiyaan na dharon. I was a spot witness to the tenor of events that evening. The Times Group general manager’s wife Mrs Umashankar, being the vocal one in the committee, made it amply clear, from the outset, that she was going to vote for Vani. Her emphatic way of putting it had three judges (of the four remaining after Mrs Umashankar) following ritualistic suit. That left Snehlata Podar alone favouring Lata. The soft-spoken Snehlata, the picture of grace as our hostess that evening, argued for Lata in well-reasoned tones. But, in the end, it was the Mrs Umashankar-led, Vani-favouring point of view that prevailed. Snehlata Podar, each time I ran into her after that, would remind me about how Lata it should have been (for Baiyaan na dharon). Yet, to this day, the Gulzar-written, Vasant Desai-tuned Bole re papihara is remembered, in the new-dew voice of Vani Jairam, as the 1971 Guddi chartbuster that caught the imagination of young and old alike. Anuradha Paudwal’s assault on the Mangeshkar hegemony –through Gulshan Kumar’s T-Series in Hindustani film music–came much later.

It was Vani Jairam who, single-handedly, cleared the thorny path for Alka Yagnik, Kavita Krishnamurthy & co. to get a fairer public hearing. Vani’s Bole re papihara, therefore, has a special slot in our song thesaurus. All the more so as, mysteriously, Lata’s Aa jaa re pardesee (1958, Madhumati) came to displace, in the film, Vani’s 1971 Hari bin kaise jiyun ree Meera bhajan (SP BOE 2351), recorded for Guddi and set to go on Jaya Bhaduri. (Towards the end of the film, in a party scene, Jaya Bhaduri lip-syncs the Madhumati melody, Aa jaa re pardesee, which replaced Vani’s bhajan). No explanation forthcoming from the music-oriented Hrishikesh Mukherjee for this midstream change of thoroughbreds! Yet, if Lata felt shaken by the Baiyaan na dharon setback, it was only a momentary loss of poise. Vani Jairam was but the latest of quite a few thrush-threats Lata had warded off. In no time at all, Vani was shunted to Madras –there to overtake, at best, P. Susheela, famous through the years as the Lata of the South.

Bole re … Lata challenger Vani Jairam

Come to think of it, how surpassingly clever has Lata been in handling fame, fickle fame. Something underlined in the celerity with which Lata was viewed to re-tune with quality composer Jaidev, when the vibes between the two were none too good. Lata’s idea was somehow to land Allah tero naam as a priceless Sahir–Jaidev gem adorning Navketan’s Hum Dono (1961). The moment Jaidev talked about turning to M. S. Subbulakshmi for the articulation of such a landmark bhajan, our diva rang that ultra-creative composer to say that there was this nacheez, called Lata Mangeshkar, within hailing distance, here in Bombay. So why, in Allah-Ishwar’s name, was he looking towards distant Madras? At another level, Abhee na jaao chhod kar (in the same Hum Dono) had gone to Asha (as a duet with Rafi) only because Lata felt that its Raag Khamaj unveiling was sadly sullied by Sahir Ludhianvi’s double entendre in the opening line. Likewise had Lata let Sahir’s Jeene do aur jiyo (on Sheila Ramani in Taxi Driver, 1954) pass to Asha, the instant she encountered, in the song-lyric, that Chadhtee jawanee ke din hain line of suggestive thought. The white-saree image was thus sedulously preserved even if the Wrigleys’ gum-chewing Lata loved getting into jeans in the privacy of her US hotel room.

Malka-e-Tarannum Noorjehan’s own mentor, Master Ghulam Haider, had singled out Lata Mangeshkar, by mid-1947, as the voice destined to rule India by the sheer power of her vocal magnetism. Earlier, ruling Hindustani songdom, as Lata cut through, was another Ghulam Haider find – Shamshad Begum. Where Shamshad charged Rs 900 for a song, Lata had been prepared to settle for Rs 50. Yet Shamshad never knew what struck her as Lata crushed all opposition. Shamshad Begum herself got to the crunch of the matter as she once told me that, when she came to render Dar na mohabbat kar le as a Naushad-tuned duet with Lata for Mehboob’s Andaz (released early in 1949), she logically assumed –following her runaway success under that composer’s baton in Nargis–Dilip Kumar’s Mela (1948) –that her voice was going on the same heroine, Nargis, in Andaz too. All the more so as the vocals of Mela ‘Mohan’ Mukesh were set to go on the same Dilip Kumar assigned to play the same Nargis’s hero in the 1949 Mehboob film. It therefore came as a career shock to Shamshad Begum to see her vocals fixed on sidey Cuckoo in Andaz.

Jaidev–Lata sought him out for Allah tero naam

Lata, after beginning to dethrone Shamshad Begum, still had (as already underlined) to ward off Geeta Roy, unique in her ‘throw’ of words. Geeta had the additional gift of being able, touchingly, to spiritualize her vocals, a trait significantly 1950-underlined, on Jogan Nargis, via He ree main toh prem deewanee meraa dard na jaane koee. This was a Jogan Nargis so devotional at heart as to be beyond the reach of the film’s hero, Dilip Kumar, for all his proximity to this very leading lady in Mela and Andaz! Miraculously, Lata took Geeta, too, in her velvety stride, side by side marginalizing all female competition, not least the hapless Asha Bhosle. In fact, all through, Lata faced no real threat, once Geeta’s anti-Waheeda Rehman standoff (with Guru Dutt) culminated in that enchantress’s leaving, at long last by end-1960, the sultry sirenish female field clear for Asha. For an Asha Bhosle beginning to peak late (only by October 1957) in the charismatic custody of O. P. Nayyar, the one composer to spurn Lata all through his volatile career. Maybe Lata hated OP’s guts. This could be because the point–sticking in the singing gullet–was carried to Lata that, in the privacy of his ‘Sharda’ home, OP habitually poked fun at rival music directors for being slave driven by ‘Madam’ Mangeshkar. Once, in my presence, OP indulged in a bit of raillery at the expense of Naushad who had come up with no fewer than four Lata renditions on Vyjayanthimala, each proving an instant hit in Dilip’s Kumar’s Gunga Jumna (1961) –among them, Do hanson ka jodaa bichhad gayo re (in Raag Bhairavi) and Na maanoo na maanoo na maanoo re (in Raag Pilu). But it was the other Raag Pilu Lata-hit in the film, Dhoondho dhoondho re saajana, that had OP in a tizzy, as I told him that we found the number highly hummable. I mean the Lata lovely on Vyjayanthimala playing Dhanno, a Dhanno –‘the morning after’–Gunga-remembering, and celebrating, in the vein of Dhoondho dhoondho re saajana dhoondho re saajana more kaan ka baala. Its pleasing Pilu tone was a reminder of Nayyar’s being, instinctively, associated with this raag as he composed all nine songs of Phagun (1958) in its Kaafi thhaat shading. Whether Raag Pilu was OP’s pet peeve here, there is no way of telling. But OP burst out: ‘You call Dhoondho dhoondho re saajana a composition by Naushad for Lata? It’s not worth a second hearing!’

OP’s sour-grapes outlook was sad, very sad, caddish behaviour in no way acceptable and I told him so. But OP remained irreverent as ever. A habitual running down of Naushad by fellow composers was a phenomenon with which I was quite familiar. But OP’s Dhoondho dhoondho re dart was clearly aimed at Lata – via Naushad. In vain did wife Saroj Mohini Nayyar plead that, to her ears, the song was a situationally apt composition in Raag Pilu. But O P remained unimpressed, dismissing it as ‘just routine rhyming’. Clearly, it was Naushad envy speaking! Did OP then fear no one? Oh yes, he feared Madan Mohan all right, being careful never to fall foul of our ghazal lord. OP well knew that Madan Mohan, being strong of boxing arm, was capable of giving a black eye to anyone who said something male chauvinistic about his raakhi-sister Lata.

Yet there were times when Lata too acted churlishly. Like after the Cine Society-organized ‘Retrospective of Suraiya’s Films’ (21–26 March 1994) at the Yashwantrao Chavan Centre in South Bombay. As the spotlight was thus momentarily back on our singing-star, Suraiya and Lata encountered each other at a film function. Here is where Suraiya felt it keenly, as Lata royally ignored her when our singing-star went up to greet her. ‘I regretted venturing to be the first to so greet Lata,’ Suraiya told me. ‘After all, I was her senior, so it was Lata who had to walk up and wish me. But Lata had achieved such a standing by this stage that I decided to waive all thought of seniority. To recall the position as it then prevailed,’ added Suraiya, ‘how Lata came as a struggler to the dominant Husnlal-Bhagatram duo at a time when I was established as a singingstar with my own pull. Lata’s attitude, then, was so deferential towards me, as the two of us dueted together on Husnlal-Bhagatram’s O o o pardesee musafir kise karta hai ishaare, for Wadia Movietone’s Balam, set to release late in 1949. That recording, I recall, came about three-four months after my early-1949 jubilee movie, Badi Bahen, in which Lata, deservedly, had a couple of hits on Geeta Bali –Chale jaana nahein and Jo dil mein khushee ban kar aaye–as Husnlal-Bhagatram put her rigorously through her vocal paces. Lata just outclassed me in that Balam duet. Incidentally, Lata also outclassed herself when she failed to return my greeting by acting so distressingly distant.’ Whereupon, I asked Suraiya: ‘Why then had you so earnestly requested Lata-love C. Ramchandra to employ her as your playback in the 1949 Duniya? You once said you did it to be able to spend more time with your Dev [Anand]. How could you possibly think of chucking a flourishing singing-star career when you were still at your tuneful zenith?’

Suraiya’s numbing response: ‘When you are in love, you are in love. Nothing else, just nothing else, matters at that highly emotion-charged moment in your life. What was the aura of being a mere singing-star compared to being so madly in love with Dev? Compared to Dev’s being even more madly in love with me? All I could then think of was my love for Dev – Suraiya as a singing-star and her career be damned!’

Her stardom for a song? Well, Suraiya did sing on, courtesy Naushad. But such was Lata’s sway, by 1955, that none dared query her unique singing pedestal. In fact, what a flutter was caused, in the Bombay film industry during the mid-1950s, as Baburao Patel’s Filmindia prominently announced, on its cover, Lata Mangeshkar as the music director of M. V. Raman’s Jhooki Jhooki Ankhiyan. Our music makers ran for cover as they beheld that Filmindia cover! If Lata herself was to compose for films, who was going to sing their songs, created for her and her alone? Lata had already scored music in Marathi films under the pseudonym of ‘Anandghan’. Even so, at this crunch point, she shrewdly chose to keep her composing powder dry in Hindustani cinema –by noting that her name, as the music director of Jhooki Jhooki Ankhiyan, had been announced without proper permission. Hrishikesh Mukherjee did venture, some 25 years later (in 1970), to get Lata to compose for Rajesh Khanna– Amitabh Bachchan’s Anand. But Latapolitely declined. Imagine, if she had agreed, who would have brought form and colour to Salil Chowdhury’s proudest-ever composition, Na jiyaa laage na –in Raag Gaara on Sumita Sanyal?

Thus, down the years, steering cleverly clear of wielding the baton, did Lata rule, untouched. Any threat that Suman Kalyanpur, Vani Jairam, Sulakshana Pandit, Hemlata and Anuradha Paudwal –all genuinely talented –later mounted remained transient in the grand sum. Madan Mohan said it all when he emphatically stated: ‘We music directors, as a Metro–Murphy team, went all over India, end-1956, only to discover there is no one even remotely as good as Lata. It is our great good fortune that Lata happened in our time.’ One thing about Madan Mohan, he was always candidly forthcoming, far more capable of standing up for his Lata than the mild-mannered Roshan, though both composers were truly gifted. Both had early-career problems at the box-office altar. But Roshan came out of it sooner with Barsaat Ki Raat (1960). Followed, majorly, by his 1963 Filmfare Best Music award-winning Taj Mahal. In Taj Mahal, Lata’s Bina Rai lip-synched Khuda-e-bartar teree zameen par (in Raag Mian Ki Todi) and her Jurm-e-ulfat pe humein log sazaa dete hain (in Raag Gaud Malhar) both compared favourably with the finest by Madan Mohan. How Roshan played around with his pet Raag Yaman! Whether it be Lata (Aeree aaleepiyaa bin in Raagrang, 1952). Or Asha Bhosle (Nigaahein milane ko jee chahtaa hai on Nutan in Dil Hi To Hai, 1963). Or even Sudha Malhotra (Salaam-e-Hasrat kabool kar lo meree mohabbat kabool kar lo on Azra in Babar,1960). As for Roshan’s Yaman Kalyan exposition of Rafi’s Man re tuu kaahe na dheer dhare (on Pradeep Kumar in Chitralekha, 1964), is it not simply ethereal? Whether it be Mukesh’s Kidar Sharma-written Teree diniyaa mein dil lagtaa nahein (inRaag Darbari Kaanada on Raj Kapoor in Bawre Nain, 1950) or Manna Dey’s Laagaa chunaree mein daag (in Raag Bhairavi from Dil Hi To Hai, 1963), Roshan was right there. Imagine how Lata fought fiercely for Roshan –against O. P. Nayyar’s supplanting him in Mehbooba (1954)–only to deny this super composer when it mattered most. Her Rahein na rahein hum mehkaa karenge could well have been Roshan’s rueful Raag Pahadi retort to such sudden loss of Lata primacy. Not many know that, in Asit Sen’s 1966 Roshan-scored Mamta, after Lata created her Rahein na rahein hum impact on the double role-essaying Suchitra Sen, it is Suman Kalyanpur vocalizing the same Rahein na rahein hum on the younger Suchitra Sen in the latter half of the film. But almost everyone knows that, near inevitably, no 78-rpm record of the Suman edition was issued by HMV.

Jiyaa beqaraar hai …Shanker (extreme right) started out as an assistant to

the Husnlal-Bhagatram duo. At centre is Husnlal, at left is Bhagatram

From Suchitra and Mamta in mid-1966 to beginning-1981. Let us move on to Rekha looking so irresistible as Umrao Jaan. Was it ever Lata, all the way, on Rekha playing Umrao Jaan, in the Asha-on-Rekha theme so entrancingly tuned by Khayyam? What if I tell you that, originally, it was Jaidev, not Khayyam, scoring the Umrao Jaan theme for Rekha? If I tell you that it was Lata, not Asha, upon whom cineaste Muzaffar Ali had zeroed in –as the voice of Umrao Jaan Rekha? Indeed Jaidev had invited me to his Lily Court music room (opposite Churchgate Station in Bombay) for a foretaste of the flavour he planned to bring to the vocals of Lata and the visuals of Rekha. Saying he was creating the score of a lifetime for Rekha as Umrao Jaan, Jaidev proceeded to play for me the eight songs he had already composed for the Muzaffar Ali classic to come. What enchanting hearing at least five of those compositions made! So much so I asked Jaidev if it simply had not to be Lata on Rekha? ‘Five of these songs are tuned to go in the voice of Lata on Rekha,’ revealed Jaidev. ‘We’re only waiting for Lata and poet Shahryar to join us.’ But what was not to be, was not to be! There was a money dispute with Muzaffar Ali, for the idyllic idea to fall through. Jaidev came to be replaced by Khayyam and in came Asha Bhosle. It is a point of pride with Khayyam that he lowered Asha’s scale by ‘half an octave’ to get the vintage vocal-visual effect he did on Rekha. But, with Jaidev and his five Umrao Jaan gems for Lata, there was no octave adjustment needed at all! Asha on Rekha proceeded, beyond doubt, to sing Umrao Jaan like the champion of champions. Shahryar heart-holders–like Dil cheez kyaa hai, Justjuu jis kee thhee, Ein aankhon kee mastee and Yeh kyaa jageh hai doston – would these ghazal pearls have glinted, as of any less value, in the vocal custody of Lata?

Totally contrary to Khayyam in style were two composers from the Bengal school, S. D. Burman and Salil Chowdhury, both coming to divine, early, the limitless vocal potential of Lata. Taxi Driver, as SD-composed, was a film to which Lata drew my attention as I met up with her in her home. Lata pinpointed her style of singing, in this 1954 Navketan film, as demonstrative of her inherent ability to ‘do a Geeta’–if she felt like it. On Chetan Anand’s Sheila Ramani, playing that Taxi Driver-calibrating cabaret dancer, Lata fleshed out, for special vocal mention, her studiedly vamped renditions of Dil se milaa ke dil pyaar keejiye; Ae meree zindagee; and Dil jale toh jale. Highlighting them as three numbers representative of a genre she shunned, soon, to reserve herself for something weightier, like the same S. D. Burman’s Jise tuu kabool kar le on Vyjayanthimala in Bimal Roy’s Devdas (released in January 1956).

Whether it was S. D. Burman or Salil Chowdhury composing for the Bimal Roy banner, it had to be Lata singing for the heroine. SD did venture to manage without Lata on Nutan in Bimal Roy’s Sujata (1959). Asha, in that film, even came up with a serene Raag Pilu beauty –on Nutan as Sujata hankering for her Adheer (Sunil Dutt) –in tones of Kaalee ghataa chhaye moraa jiyaa tarsaaye. Only for Lata to stage an N54137-return, via the same S. D. Burman on Nutan, with Jogee jab se tuu aayaa mere duaare, as Bimal Roy’s 1963 Bandini. A Bandini situation trying enough for Asha movingly to N54138-plead: Ab ke baras bhej bhaiyya ko baabul saawan mein leejo bulay re. Brother Hridaynath Mangeshkar to note! Yes, Asha Bhosle as singing competition, Lata just ignored well beyond 1950. Why not, when each prized tune, from each top composer, would still come to Lata and Lata alone? Queen Bee, Lata certainly was in the era ‘When Melody Was Milady’. This early Lata lustre remains undimmed 60-plus years after she arrestingly arrived in 1948, on the doe-eyed Nalini Jaywant in Anokha Pyar, via the Zia Sarhady-written, Anil Biswas-tuned

Yaad rakhna chaand taaron is suhaanee raat ko

Yaad rakhna chaand taaron is suhaanee raat ko

Do dilon mein chupke chupke jo huuee so baat ko

Do dilon mein chupke chupke jo huuee so baat ko

Yaad rakhna chaand taaron is suhaanee raat ko

Yaad rakhna…