The Perennial Promise of Airships

At four in the afternoon on Wednesday, October 28, 2015, a Pennsylvania State Police officer fired a hundred shotgun blasts into the nose of a runaway blimp. The milk-white blimp, caught in a tree, sank to the ground as helium whistled from the shotgun holes. As the helium leaked, a team from the United States Army rolled up the blimp’s tail, which had separated when it crashed. From the tail a 6,700-foot Kevlar tether snaked across the rugged, wooded terrain. A team cut the tether with carbon-steel-bladed scissors—Kevlar is used for bulletproof vests—into small sections, which another team loaded onto a truck.

Four hours earlier, the blimp had broken free of its mooring at the Army’s Aberdeen Proving Ground near Baltimore, Maryland. Although designed to always be crewless and tethered to the ground, the 242-foot-long blimp had traveled 160 miles north, crossed into neighboring Pennsylvania, and dragged its mile-long tether along the ground, terrifying local residents. Fortunately, no one was injured or killed. The whip-like cable, however, destroyed two million dollars’ worth of power lines—a pittance compared to the now-destroyed blimp’s $175 million cost.

The escaped blimp was part of the $2.7 billion Joint Land Attack Cruise Missile Defense Elevated Netted Sensor System (JLENS). It held aloft a radar high enough above the horizon to detect cruise missiles, drones, and other low-flying weapons. Despite its high price tag, the Pentagon rated JLENS as “poor” in reliability, unable to provide twenty-four-hour surveillance. It was labeled as “fragile,” Pentagon-speak for “did not demonstrate the ability to survive in its intended operational environment.” Critics called it a “zombie” government program: one that feeds on cash and is impossible to kill. It survived with the same justification used by proponents of lighter-than-air craft who aspired to create more than a novelty like the Goodyear blimp or the mere utilitarian and humble weather balloon. The wayward military blimp’s promoters promised that this newest version of a lighter-than-air craft would solve one of the most pressing problems of our time. The JLENS blimp would watch the skies and sound the alert at the first hint of an aerial attack from a rogue group or nation.

The front-page news of the runaway JLENS blimp was just that: news to almost all Americans and others around the world. Who knew we used lighter-than-air craft for anything besides covering the Super Bowl or golf tournaments? To several generations, an airship means a zeppelin, and their image is of the Hindenburg burning in the sky. Yet airships have a rich history beyond that of the iconic zeppelin.

The story of lighter-than-air craft is one of empire and national pride, of technological advances and human perseverance, of ego and bravery. While the story of winged flight is prominently part of every history textbook, that of lighter-than-air craft, though more glorious and tragic, is largely untold in the modern day. In their heyday—between the First and Second World Wars and before transcontinental airplane flight—airships the size of the Titanic were the preferred method of travel between continents.

The allure of lighter-than-air craft to solve pressing problems can be traced back for decades. In 1997, six years after the first web page was posted, a company called Sky Station solicited $4.2 billion to built 250 antenna-equipped blimps to deliver Internet service. In May 1985, the British Antarctic Survey revealed a hole in the ozone layer over the South Pole, and a few years later a professor suggested sending blimps that dangled electrical wires to zap ozone-eating chemicals. In the 1970s, the Aereon Corporation proposed a hybrid lighter-than-air craft that would take off like a jet, then float like a blimp. This aerial workhorse would inexpensively usher all nations into the twentieth century—no need for costly infrastructure such as roads, railroads, tunnels, bridges, airports, warehouses, or harbors. In the 1950s and 60s, when nuclear fuels promised unlimited energy, a Boston University professor proposed a nuclear-powered version of the airship.

The airship—the largest version of any lighter-than-air craft—carried the heaviest payload and traveled at the highest speed of any lighter-than-air craft. This superior performance occurred because an airship’s construction differed dramatically from that of a free balloon or a blimp. The latter two are both pressure vessels: their shape is maintained by the pressure of the lifting gas. In contrast, an airship’s shape is formed by a metal framework. The metal skeleton houses gas bags that lift the ship, and a cloth cover stretched across the framework protects the gas bags from weather. This structure enables an airship to travel faster than a blimp: the force of the wind generated deforms the nose of a blimp, while the framework of an airship keeps its nose rigid when cutting through the sky.

The greatest advantage of the airship’s more complex structure is the larger payload it can carry. For example, the proposed nuclear-powered airship was to be 980 feet long and would haul 400 passengers and ninety tons of cargo. “For freight,” explained the ship’s designer, like “motor cars and other bulky manufactured equipment, the airship would offer the lowest per ton-mile costs between factory and destination.” These characteristics of an airship appealed not only to commercial interests, but also to governments with imperial ambitions.

In 1898, the U.S. annexed the Philippines as part of the spoils of the Spanish-American War. President McKinley promised to “educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them,” though he worried his “civilizing” of the Filipinos might be impeded by Japan, the rising power in the region. American fears increased in 1905 when Japan surprised the world with its victory over Russia. If war occurred in the region, Japan could seize the Philippines: they were just 2,000 miles from Japan; the U.S. was 8,000 miles away. It would require sixty days for an American fleet to reach them. To create an early-warning system, the U.S. Navy commissioned three large airships for long-range strategic reconnaissance of the Pacific Ocean. Only an airship had the range and endurance to traverse the Pacific quickly and warn of approaching Japanese ships.

Not having the technology in hand, the U.S. military built, in the 1920s, an airship based on a zeppelin captured in the First World War; they also bought an airship from Germany’s Zeppelin Company and one from the British government. Although two of these ships crashed, their performance so impressed the military that they decided to build two airships twice the size of the test ships. Construction of the first ship, the USS Akron, began in 1929, and of the second, the USS Macon, in 1931. Almost 800 feet long, they were dubbed flying aircraft carriers.

Airships revitalized Germany’s national psyche after the First World War. When the Graf Zeppelin flew over the country in the 1920s, it soothed the sting of defeat by evoking, for Germans, their prewar imperial glory, and the airship hinted at the nation’s return to the world stage. Because zeppelin-style airships originated long before the First World War, their appearance in the skies awakened memories of Germany’s proud, industrial past. Count Zeppelin designed his first airship in 1874, fourteen years before the militant Wilhelm II became Kaiser. The first zeppelin flew in 1900. This twenty-six-year gestation of a German airship, from design to flight, coincided with Germany’s rise as Europe’s foremost industrial power. Its production of steel, chemicals, and coal increased by factors of ten until Germany rivaled the output of the United States.

A zeppelin, in size and symbolism, recalled pride in a bygone imperial era when the nation’s authoritarian government ran the country with efficiency: the trains ran on time, the streets were clean, and its superb schools drove the literacy rate to over 90 percent. Germany’s public universities were models for the world. German scientists won a third of the Nobel Prizes for science awarded from the first one in 1901 until the outbreak of war in 1914.

“What a paradise this land is!” said Mark Twain after a visit to imperial Germany. “What clean clothes, what good faces, what tranquil contentment, what prosperity, what genuine freedom, what superb government!”

After the war, this imperial culture, its institutions, traditions, and values, were shattered beyond repair. The stability of the prewar era was replaced by an intellectual free-for-all in the Weimar Republic: expressionism in arts and literature, exotic Bauhaus architecture, atonal music, and, in science, the revolutions of relativity and quantum theory. In this disconcerting flux, the return to the air of a German airship, an icon of the imperial era, comforted the German public, and it signaled to the world that Germany would overcome the impediments of the Treaty of Versailles. Small wonder that spectators broke into tears of joy when they saw a zeppelin, or that one teacher required his students to salute it and sing the national anthem.

For Britain in the 1920s, there was no nostalgic view of airships; they were of current and immediate political importance for maintaining global dominance over disparate lands and continents. “Distance,” said a British official, is the “enemy of Imperial solidarity” and only advances in flight—like a giant airship—could bring “closer and more constant the unity of Imperial thought, Imperial intercourse, and Imperial ideals.” Airships “will knit together,” said another official, “the scattered peoples of the British Commonwealth.”

At that time, Britain’s Empire covered a quarter of the world and encompassed a fifth of its population. This great sweep included India, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Pacific islands, and a swath through the center of Africa—from South Africa through Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe) to Egypt. Communication across this vast area was, to many, the most significant existential threat to the Empire after the defeat of Germany and its allies in the First World War.

These postwar years were characterized by George Orwell as “the golden afternoon of the capitalist age.” In that era, “almost every European,” Orwell explained, “lived in the tacit belief that civilization would last forever … nothing would ever fundamentally change.” For the politicians who sought to sustain and strengthen the Empire, the problems were, as one historian said, “a temporary and curable disorder.”

Indeed, in 1924, as Britain planned a fleet of imperial airships, threats to the British Empire seemed feeble. In India, Gandhi was serving a six-year sentence for civil disobedience. In Germany, Hitler, guilty of high treason, also sat in a prison. The U.S.S.R. sputtered as Lenin lay ill and dying. To preserve the Empire, then, the British developed aviation to control the movement of mail, cargo, and people. It was a job for a grand airship instead of a feeble airplane. “An airplane,” wrote one advocate for airships, “is little more than a very high-powered automobile with the mudguards extended laterally to provide surfaces for lifting itself off of the ground.”

Airships far surpassed the planes of the day in range and lift. An airship could travel 2,500 miles before refueling, ten times as far as an airplane, and an airship lifted thirty or forty tons, while an airplane carried a single ton payload. With their great range and lift, airships could crisscross the Empire and move vast amounts of commodities, deliver tons of mail and parcels, and transport hundreds of citizens.

To serve the needs of Empire, the British began construction in 1927 on two airships. One, R.100, was built by private enterprise, although partly funded by the government; the other, R.101, was built directly by the government at their Royal Airship Works. The “R” in these names was short for “rigid” to indicate an airship rather than a blimp. These British ships surpassed in luxury the Graf Zeppelin and the American airship, Akron. Each featured a spacious lounge, a dining room that seated fifty, sleeping accommodations for about fifty passengers (although the original plans had called for one hundred), glass-walled promenade decks, and, in R.101, a smoking room. After the test flights each ship was assigned a long-distance demonstration flight to prove the prowess of airships: R.100 was to fly to Canada and R.101 to India, the latter the politically more important route.

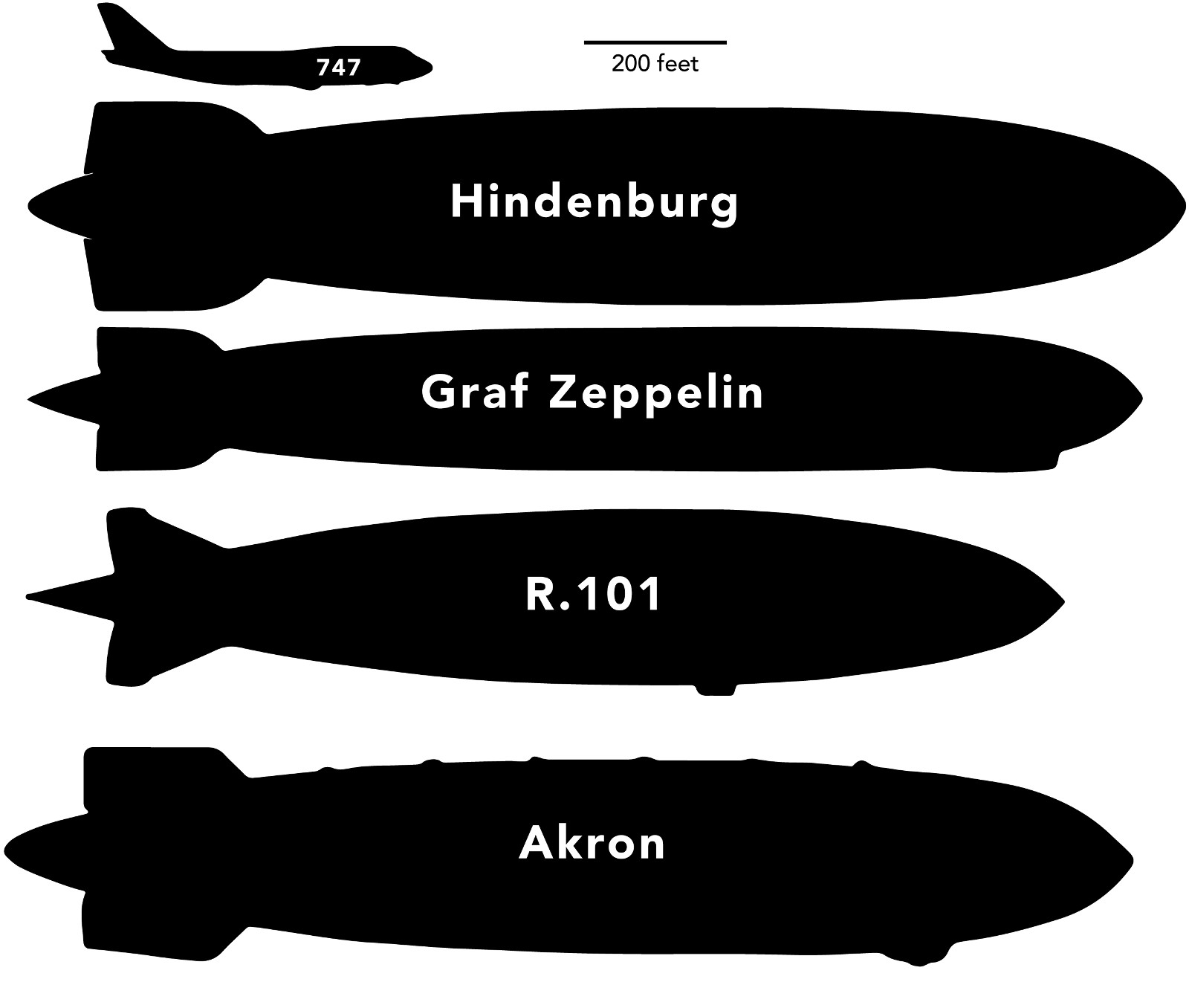

Relative Sizes of the Hindenburg, Graf Zeppelin,

HMA R.101, and USS Akron

In 1929 R.101 was the largest airship in the world. The Graf Zeppelin (LZ 127), a contemporary of R.101, was forty feet longer but R.101 had a larger cross section and so held 30 percent more hydrogen—4,893,740 cubic feet for R.101 versus 3,707,550 cubic feet for the Graf Zeppelin. The U.S. finished construction of the Akron after R.101 crashed. The Akron had a volume of 6,850,000 cubic feet, so was larger than R.101 and the Graf Zeppelin. The Hindenburg was larger than all of these ships, but was not built until 1938.

India, said Prime Minister Disraeli in the late nineteenth century, was the “Jewel in the Crown.” This alluded to the deep financial ties between Britain and India, ties which grew stronger in the twentieth century—£800 million invested in India from trade in rubber, coffee, indigo, tea, coal, and jute. Beyond the tangible financial links and the geopolitical importance of India, the emotional bonds between the two cultures ran deep. By the 1920s, Indians were Members of Parliament, one even a Peer of the Realm, and the British public thrilled to the exploits of Indian cricket stars. And India permeated the psyche of Britain’s upper class: the prominent Anglo-Indian families thought of themselves as having dual nationality. To sustain the bonds between the two countries, the British government assigned the India air route to R.101, considered to be more innovative than R.100.

R.100 was “no more than a rehash of the German [zeppelin] methods,” said Britain’s most prominent airship captain, Major G. H. Scott, “and therefore the last of an outdated form of construction.” He celebrated R.101 as “of entirely novel design, embodying the latest and most up-to-date materials and engineering methods, and we regard it as the first of an entirely new series, and decided to use the number R.101, that is the first of a new series.” The British expected R.101 to spearhead a fleet of imperial airships that would dominate the skies as British naval ships, a century earlier, had ruled the seas. Germany owned the commercial skies from Germany to the Americas—Berlin-to-Rio by zeppelin was de rigueur for any German of wealth and stature—but Britain had grand plans of maintaining its Empire around the globe, and the airship was central to those.

The interplay of engineering and commerce, of the careful methodology of the ship’s builders and the reckless vision of politicians, of money, power, and global influence led to the tragedy of R.101. Although, in the end, the ingenuity and bravery of one person brought the dream of R.101 close to realization: Noel Atherstone the ship’s First Officer.

The diaries of Atherstone, found after his death, illuminate the history of R.101 and enrich the pages of this book. Without his bravery, the ship may never have flown, and without his words we would not have as complete a record of the day-to-day struggles in creating R.101.

A colleague of R.101’s officers and crew said of their work: it is “an example of admirable corporate courage which those who write airship history should appreciate and recognize and those who write for popular interest should respect.”

I hope this book meets this standard.