14

GOING GLOBAL AND THE BIRTH OF THE MICRO NETWORK

One of the questions I get asked most often is: ‘what has been the biggest change in advertising over the last 40 years?’

It’s easy to look at the role of technology and talk about the digital revolution, which undoubtedly is amazing, but whenever I answer this question I talk more about the globalization of the advertising business, which, of course, is a result of technology. The important issue here is that we must remember that it isn’t just technology that makes a difference, but how we use it also creates change.

We all know that the phenomenon of mobile texting came about not because mobile phone operators understood its value to their subscribers – it was never viewed as a consumer product – but because subscribers recognized the value of short, sharp messages that could be responded to at the receiver’s leisure. || And, of course, it was very cost-efficient: never forget that.

It’s always important to remember that it’s not the technology that matters, but what we do with it.

Remember Walkman? I bet Sony wish we would. It was a brilliant innovation based on existing technology. The genius was making taped music mobile. However, it seems Sony became obsessed with making tapes smaller instead of adopting digital technology and expanding our mobile music collection exponentially.

Technology has created the opportunity for our ideas to go global. Naturally clients have leapt upon this opportunity, which allows them to control their image and reduce costs. || Why have 10 commercials when you could just have one? || It’s a no brainer for many big corporations. || But in our rush towards globalization have we also lost our ability to touch people? In many cases we have. Creating work that can cross borders has too often ended up with the adoption of some ‘amazing’ technique instead of an idea. This is lazy thinking, too often born out of the difficulty of getting a number of clients from the different regions to buy in to the idea. || It’s easier selling a technique – ‘Hey, we’re going to get the buildings to dance!’ – as opposed to a powerful idea that moves people. The often-heard reaction – that won’t work here – is hard to argue against. Dancing buildings work everywhere. Or do they?

But just as Mr Bernbach showed us how to create great advertising for the masses, so today our creative challenge is to create ideas that can cross borders and yet still touch people.

I remember an interview with J. K. Rowling. She’d just finished her Harry Potter books and was asked what age child she had in mind when writing the series. Potter goes from age eight to 18. || She said she didn’t, she wrote them for herself. She created something that touched her and, in doing so, touched millions.

That’s the best advice anyone can give if you’re trying to create work that talks to a global audience.

Our work at BBH for Levi Strauss showed that creativity could cross borders, yet still be acclaimed. This is a pretty basic point if you’re building your agency’s reputation on creativity. It was out of this experience that we developed the craft of visual narrative: telling a story without words. || I would provocatively say to our writers: ‘words are a barrier to communication’. Not because I didn’t value them – I did – but all too often they were over used to explain an idea instead of enhancing it.

In the early days of BBH our desire to create work that could cross borders opened up a number of interesting creative opportunities for us. The most unusual was a project for Pepsi.

Kevin Roberts, who now runs Saatchi & Saatchi globally, had contacted us after seeing our 501s campaign. At the time Kevin was managing director of Pepsi’s business in the Middle East. It was their most profitable region outside the US. Why the Middle East? Think about it for a moment and you can see why: it’s unbelievably hot, consuming alcohol may result in eternal damnation and (not least) Coca-Cola were embargoed because of their presence in Israel. I’m not sure what was more profitable at the time: just printing money or bottling Pepsi and selling it in the Middle East.

Who needs advertising, you might ask?

The reason BBH was given this brief was because of Pepsi’s belief that the embargo on Coca-Cola in the Middle East was going to be lifted. Which eventually it was.

Once that happened Pepsi would have some real competition. With this in mind, Kevin decided it was time Pepsi engaged with their customers’ emotions and not just their thirst. They needed to build some brand loyalty.

Now, if you think there are restrictions in creating global advertising wait until you get to a place like Saudi Arabia. I think the censors there would recoil from a blank screen. However, despite the challenges the advertising would face, he believed we could create something distinctive.

Remember: focus on the opportunities, not on the problems.

Kevin provided BBH with one of the best briefs I’ve ever been issued. He explained that when he went to New York for the annual global Pepsi get-together each region from around the world presented its advertising in order of value to the company. Naturally, the US, as the biggest market, went first, followed, for the reasons I explained earlier, by the Middle East, presented by Kevin. Just to make matters worse, the US division of Pepsi had some genuinely outstanding advertising at that time. Their ‘Choice of a new Generation’ campaign, which used famous stars, had everyone talking. Mind you, the commercial in which Michael Jackson’s hair burst into flames wasn’t exactly the kind of headline they were looking for. The director of that spot, Bob Giraldi, told me how it happened: Jackson was scripted to make an entrance through two walls of fire. I know, not exactly original! Anyway, on the command ‘action!’, young Michael bounded through the explosions of fire. The only problem was that he had so much hair lacquer on that his head burst into flames. This is one of the sad outcomes of over-coiffured hair. Unfortunately for Michael, someone hadn’t bothered to read the ‘highly inflammable’ warning that usually appears on the side of hair sprays.

At its heart, Kevin’s brief to me was simple: when he stood up to present he didn’t want egg on his face! Now that, as a brief, is brilliant. You know exactly where your client is coming from and the reaction they want from your work: it’s got to stand up to scrutiny by a sophisticated but jaded marketing community in New York.

I think we delivered with a completely mad piece of advertising that got through the Saudi censors and was a hit in New York. It can be done.

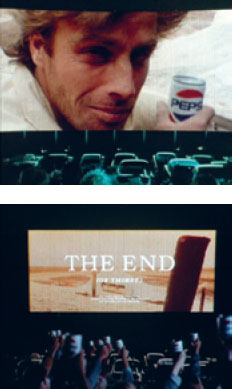

We shot a two-minute spot in the Australian outback that was a cross between Raiders of the Lost Ark and a James Bond movie starring the refreshing taste of Pepsi. || It was so over the top it was funny. Interestingly, the more ridiculous and absurd we made it, the fewer problems the censors had. ‘The thirst’ became a hit.

We had to make sure everyone held the hero can of Pepsi in their right hand. Apparently, in Saudi Arabia if you don’t you’re insulting everything that’s sacred to Arabian culture. And that can really piss off a lot of thirsty Saudis.

While we were working on the Pepsi campaign I went to Jeddah to familiarize myself with the market. It was the weirdest place I’ve ever been. I remember being taken to a very smart department store by the Pepsi people, Jeddah’s answer to Harvey Nichols or Bloomingdales.

Walking around the store we passed through the cosmetics department. I don’t normally spend a lot of time in cosmetics departments, but the ensuing scene enthralled me.

Standing there were three veiled women, covered from head to toe, trying on Chanel lipstick. They were being served by a man as women weren’t allowed to work in Saudi Arabia.

Client: Pepsi, 1985 Title: The Thirst Art director: John Hegarty Copywriter: Barbara Nokes Director: Iain MacKenzie

It was one of the strangest things I’d ever seen. The three women would each select a lipstick, take it up under their veil, apply some, put the lipstick down and pick up a mirror that would also then have to go up under the veil so they could check out the lipstick. I stood there mesmerized by this performance. Who knows what they could see under all that clothing or what the bearded counter assistant offered? Despite this, the end result was the purchase of several lipsticks and, therefore, an increase in Chanel’s profits. Talk about a brand giving you an inner glow! What was going on underneath that veil? And the lesson here? As alien as that culture was to me, here were three women doing something as simple as buying lipstick. It could have been Bloomingdales in New York – obviously without the veils and bearded salesman.

Back at BBH it was dawning on us that you certainly could create global campaigns from one place, especially if you were talking to a relatively young audience, but time differences and the resistance of local clients to accept our business model meant that we would have to consider opening offices in other regions.

To be fair, sometimes there are genuine differences that one region finds hard to understand about another. I suppose Wieden+Kennedy have discovered this with Nike. Their office in Portland, Oregon, has produced some brilliant global work, but consider whether, from that location, they would be able to understand the relationship fans have with football, or, as Americans say, soccer? It’s a very un-American sport, so they realized that they needed an office located in a football-soaked culture to help make Nike a credible player in this global sports arena. As a result, Wieden+Kennedy opened an office in Amsterdam and Nike, an American brand, are, I would argue, now a credible force in football.

It’s important to have beliefs. It’s also important to know how they have to evolve.

But the big question for us and our ambitions was how many offices should we open and where should we start?

It seemed to us there was no point in trying to compete with the major networks. We’d seen TBWA try to do this. || It’s not impossible, but before you know it you’re spending more and more time administering a complicated network of offices. It’s hard enough managing one office, but to manage 20, 30, 40? Forget it.

If you administer a large network the passion about the work rapidly dissipates. It becomes a process rather than a principle. It does wonders for your airmiles, but nothing for your creativity.

So we started talking about the ‘micro network’. A network of a few offices located in important economic centres – between seven and ten offices at the most. This made much more sense for two main reasons: one, it was manageable, and two, we sensed a desire from certain clients to be more impressed with the quality of ideas rather than dozens of pins on maps showing office locations.

The biggest problem certain clients had was finding a great idea. Delivering an idea on the ground was relatively easy: a big, unifying idea was the issue.

At this time, in the 90s, conventional wisdom would have said the next step in our growth would have been for BBH to take our brand to the US. We already had a number of American clients, so that would certainly have been the logical move. We would have followed a well-worn path so many agencies before us had taken. ‘Go west, young man.’ But by now we had our ‘Black Sheep’ philosophy, a philosophy born out of that very first poster we created for Levi Strauss to promote black denim: ‘When the world zigs, zag’. So we decided to zag and go east and start an office in Asia: to open up our brand to a region that didn’t at that time have a huge number of hot agencies. They certainly had some outstanding people, creatives who had brought their talent to the region and had produced some great work, but very few London creative agencies had gone in that direction. || Most were looking west, so we set our eyes on Singapore.

Starting a new office is more time-consuming than anyone ever realizes, and, I concede, more costly than they can imagine. We certainly wanted to open an office in the US (which we did, in due course), but genuinely thought we could learn a huge amount, which in due course we did, by zagging our way to Singapore.

Before we could credibly develop our global ambitions we had to have a global media partner. Without the ability to talk about media options and the reality of placing work in local markets we just wouldn’t be credible. We needed media input. Of course, we could have just gone to any media player and agreed a deal to work with them. But that would have meant handing over our client relationships to a media company for nothing.

Now, as much as I’ve said, money is the last reason to do anything, I also don’t think (and neither did John and Nigel) that our client relationships should just be handed over on a plate. They represented hard-earned business that we’d fought to help make successful. Nigel’s observation was, ‘I don’t want my gravestone to read, “he died a pauper but you should have seen his showreel”.’

It was obvious that if we were to be successful as a global agency we had to sell a stake in BBH to an agency with a respected and credible worldwide media business. We decided quite early on that there was only one option: Starcom. They were the media player we most respected and, fortunately for us, they were owned by Leo Burnett.

I say fortunately because Nigel had been a rising star at Leo Burnett in the early 70s and therefore felt an affinity with them. I think we also liked and trusted them – we very much respected what they stood for and what they had achieved. They had produced brand-building campaigns that had been globally successful and, while not exactly my kind of work, it was work that I could respect. Most of all, and this is the most important point, was this issue of trust. We weren’t looking for clones of ourselves but people who had some beliefs and knew how to spell the word integrity.

As part of this journey to find a credible partner, and before we finalized the deal with Leo Burnett and Starcom, I remember having a conversation with Jay Chiat. He was trying to put together a group of like-minded agencies that, based on creative principles, would be the foundation of a network of independently owned agencies that would become a global force. He wanted us to join him in this federation of agencies.

It sounds great in theory, but unless you’re financially bound to each other it’s impossible to make it work.

Worse than that was the fact that the first agency he’d approached to set up this network was MOJO out of Australia. Now, at that time, if there was an agency that was more different from Chiat/Day it would almost certainly be one with the initials M, O, J and O. || They put jingles on just about every piece of business they worked on and obviously had a belief that singing was better than thinking. To say I hated the work they produced would probably be an understatement.

When we expressed doubts about MOJO’s creative beliefs to Jay Chiat, never mind the whole agency network concept, he talked us into having dinner at Le Caprice in London with him and MOJO’s international chairman.

Out of respect for Jay, Nigel Bogle and I went and listened politely as he explained why he thought MOJO, Chiat/Day and BBH could be the start of a great business venture.

It was at this moment that Nigel went into what I call ‘Bogle mode’. In no uncertain terms he explained why he thought MOJO would be the last people in advertising BBH would ever want to be in partnership with. One look at their work would have convinced you of that.

Jay took it all in his stride as the bloke from MOJO nearly choked on his steak tartare, stuttering and protesting their creative credentials. Obviously, their ‘down under’ definition of creative was different from ours. I recall that he wasn’t singing: perhaps a quick jingle would have been better.

In the end, despite Nigel’s good advice, Chiat/Day did a deal with MOJO that eventually collapsed for all the obvious reasons. In the end MOJO were bought by Publicis, where thankfully they’ve made them sing less and got them thinking more. I’ve always found it advisable to listen to Nigel. Sadly for Chiat/Day they didn’t have that kind of relationship with him.

If you’re going to merge two cultures, you’d better make sure they’re compatible. Our part ownership with NeoGama in Brazil, now NeoGama/BBH, has been brilliantly successful because we all believe in the same things and buy the same kind of creative thinking. If the two are not compatible then what actually happens is that one organization takes over the other. It’s dressed up as a merger because it’s better for egos and PR.

In the advertising business most mergers don’t work. Why? An agency is a collection of beliefs – you can’t just package them up and merge them with someone else’s. || The whole thing’s a nonsense. In the end, one culture has to be dominant. You should decide, when ‘merging’, which of the cultures, if they’re different, is going to be the dominant one and get the pain out of the way early on. We certainly weren’t going to be part of a charade like that.

Our deal with Leo Burnett was certainly the best deal we’ve ever done and has benefited both them and us. We went into it with something to offer Leo Burnett – the chance for them and Starcom to be part of our expansion – and for us to gain access to the powerful and effective media company that was Starcom. We always went into it with a win-win philosophy – they had to gain as much as us.

It was important for us to maintain our independence and therefore our ability to operate as we saw fit. Our creativity and intelligence were built on that positioning. We were able to hire the best people because they knew they were working for us, not a holding company or another agency that might call the shots.

We sold 49% of BBH to Leo Burnett, valuing it at 100%, and held on to 51%, which had to be owned by people working within BBH.

Five years later Leo Burnett were sold to Publicis. At this point we could have bought ourselves back, as our original agreement had a clause about change of ownership. But by this time our relationship with Starcom was so well developed it would have been pointless. Our 51% ownership was there to protect us in any case, and to be fair to Publicis they have been great partners.

Remember: it’s a harsh world out there, you need as many friends as you can get.

We opened our very first office abroad, in Singapore, in 1995. Simon Sherwood, our London managing director, volunteered to set it up and ran it for two years. Within two years of opening the office the so-called ‘tiger economies’ of Asia crashed, which is just what you want to happen as you’re establishing a new office. Chris Harris, one of our board account directors, had just gone out to Singapore to take over from Simon. Literally as his plane touched the tarmac, the region was hit by an economic downturn. Actually, it was more like a bloody implosion than a downturn. Poor Chris. Of course we all blamed him. Talk about timing!

When I first went out to help recruit creative people for the new office I really didn’t like Singapore. I found it sterile, oppressive and narrow. There was little I liked about the place apart from the flight home. I just couldn’t understand why people like Simon and Chris wanted to go there. Culturally, I found it shallow – it was a manufactured environment, which presents a bit of a problem when you’re trying to build a creative company. We wondered if we should have gone to Hong Kong instead?

But, as time’s gone by, I’ve come to like the place more and more. It really has loosened up. It’s now a vibrant, confident, cosmopolitan centre and, importantly (and something I’ve come to appreciate), safe. I know that might sound boring, but when you look at the region around it the success of Singapore is remarkable. It’s surrounded by chaos, corruption, instability and danger, yet it is literally an island of dynamism with a cosmopolitan population who are well educated and industrious. || The true test of Singapore is if you don’t like it, no one is forcing you to stay. In fact, one of the biggest problems the Singapore government has is people trying to get in illegally.

Having weathered the Asian economic crisis, we had learnt all kinds of lessons about opening another office: make sure one of your very senior people heads it up, don’t ditch your principles because you’re in a different region, and play the long game. This, of course, requires steady nerves and deep pockets.

We then turned our attention to the US. The US had always been a difficult market to crack for British agencies. In fact, no UK agency had really made it in the US. Saatchi & Saatchi, through their merger with Compton, had established an office in New York, but it was a pale imitation of their head office in London. || At BBH we weren’t interested in pale imitations. We wanted BBH, wherever it was, to be the same: an outstanding creative company staffed by intelligent, perceptive individuals.

Historically, American agencies expanded on the back of their clients’ growth – giant organizations such as Procter & Gamble, Kellogg’s and Mars. Sadly, the days of large UK companies with a global presence have disappeared. Yes, there’s Unilever and Diageo, two of our clients at BBH, but beyond that there’s not much else. As a result, BBH had to expand on the back of our reputation. Of course, we had global clients Diageo, Unilever, Levi Strauss and Audi, but they never guaranteed us business beyond our London office – those global clients all had lots of other agency relationships around the world – so we had to fight to win their trust and show we could take our brand beyond the UK. Even Wieden+Kennedy, a contemporary of ours, had primarily expanded on the back of Nike’s growth as a global brand. I wish we could have done the same.

However, it isn’t all bad. Being in that situation does give you the advantage of deciding exactly where and what you want to be. You start with a clean slate.

When finally deciding to go to the States the first thing we had to decide was where we should locate our office. It didn’t have to be New York. In fact, in the late 90s, none of the interesting creative agencies, the companies we respected, was in New York. Wieden+Kennedy were in Portland, Chiat/Day in Los Angeles, Fallon Worldwide in Minneapolis, Goodby, Silverstein in San Francisco and the emerging Crispin Porter + Bogusky in Miami.

All the big, boring agencies, yes, you’ve guessed it, were in New York. Bizarre, isn’t it? New York is the biggest, most diverse advertising centre in the world, yet none of the challenging, interesting advertising companies is located there. || Is this the case anywhere else in the world? No. It would be like coming to the UK and finding the hottest agencies were in Doncaster or Penzance or even, God forbid, Grimsby! And I can assure you, Grimsby is how it sounds.

So, the question was whether we should be in another city, or whether we should try to make a go of it in the Big Apple? Someone once said to us that, ‘New York is the business of advertising, elsewhere is the craft.’

We decided on New York, not just because we loved the place, but also because we reasoned it gave us a chance to shine. None of the people we really admired were there (or if they had been, they’d pulled out): it gave us an opportunity to make a mark.

So New York it was. Once again, it was important that one of our senior people should go and set up the office, and that senior person was me. If BBH was going to make a statement about our intentions in the US and those intentions were based on our creative work, then the most senior creative person in the agency had to be there. || That’s what happens when you’ve got your name on the door. I have to say that I didn’t protest too much at having to go and live and work in New York.

I left London in January 1999 and Cindy Gallop, our managing director who’d worked for BBH in both the London and Singapore offices, had set up a temporary office in a block owned by Robert de Niro in Tribeca. I was hoping to bump into the great man, possibly while emptying our trashcans, but sadly no luck – I think he had better things to do. We shared the office building with Harvey Weinstein’s film company, Miramax, so the occasional sighting of a Hollywood star added a certain glamour to our surroundings and made sure we kept our eyes open in the elevator. After all, I’d already had the dubious honour of peeing next to Kirk Douglas at Pinewood Studios in the UK and kissing Lauren Bacall on a TV chat show.

The original plan was for me to go to New York for a year, help establish the office, having appointed a creative director, and then come home. None of that is what happened. Opening an office is a bit like warfare: the first casualty in a war is the battle plan. And so it was in New York.

After a long struggle we finally appointed Ty Montague to be our executive creative director. Then, nine months after being appointed, Ty decided to leave us and join Wieden+Kennedy, who were trying to establish their New York office. Ty eventually left Wieden+Kennedy and joined JWT and has now left to start his own business. If he sticks at it I think he will be incredibly successful.

Sticking being the operative word.

All of that delayed my departure. Not that I was upset – I loved New York, really enjoyed exploring the US and it was a wonderful experience – but could I have stayed? Yes, I certainly could have done, but that would have cramped the style of the people running the office. They had to feel it was their responsibility and their opportunity to make a name for themselves while not being overshadowed by me.

Remember: if the magic isn’t based on intelligence then you’re in trouble.

There were a number of lessons I learned from my time in the US. One of the most important was genuinely to understand the culture. You think you do, but you come from somewhere else and are driven by all your own prejudices – you have to be aware of them. || So whenever you go to another country make sure you really understand what motivates them, what drives their thinking and opinions.

One of the things about American culture is how people value ‘big’. To Americans that word has a cultural importance that can easily be missed by those looking from the outside. We Europeans tend to scoff slightly at the word. For us it can mean boring, corporate and unwieldy. And, let’s face it, in Europe we’ve done big and found it wanting: big empires, big wars, big glories and grand coalitions. We see the shortcomings of ‘big’ – history has taught us how the mighty can fall. For Americans, ‘big’ carries a different meaning. To them, ‘big’ is about success. The US is a big country, with big opportunities, big resources, big money and big rewards. New York is called the Big Apple, not the little apple or the average apple: it’s big. Yes, Americans’ cars are big, the people are big and their appetites are big, but that slightly misses the point.

The US was populated by the disadvantaged, the discriminated, the poor, the starving. These were often people who had suffered famine, persecution and loss. They landed in the US and found a land of plenty that was overflowing with opportunities. The size and scale of those opportunities seeped into their culture and psyche and today articulates itself in the word ‘big’. So, when you land on the shores of the US and scoff at the word ‘big’, beware.

Big is important. Big isn’t a problem, it’s an opportunity. It’s partly what made the US great.

Over here in the UK we spend most of our time convincing our European clients – those that aren’t the biggest – to play off the fact that they’re not big. The opportunity for them is to look small, nimble, more responsive. This is less the case in the US, where, with a potential domestic market approaching 300 million, you can run a very successful business being number two in the market or even number three. There are the exceptions with just two players going head to head – Apple versus Google, Pepsi versus Coca-Cola, for example – but they are rare. The advantage of the US is there’s plenty of room. It’s big. It’s expansive.

Before I set off for the US I asked a fellow Brit if there was a problem being British in New York? He said, ‘Absolutely not. You have to remember New York is a city populated by people from everywhere else. Virtually everyone in the city is an immigrant.’ He then told me that, ‘Your problem will be that when you go out to the rest of the US you’ll be thought of as someone from New York. That will be your problem.’ How right he was. New York is more different from the country it is part of than any other city in the world. It is a city that is viewed by the rest of Americans with deep suspicion.

I once said to a friend in New York that I was afraid I wasn’t getting out enough and seeing the real America. They said that I shouldn’t worry – half an hour in Duane Reade will sort that out. For those of you who have not visited New York, Duane Reade is a chain of drug stores located throughout the city that sells every kind of pill for every kind of neurosis you might possibly suffer from. Wandering around one of the stores is a uniquely American experience.

I arrived in the US at a fascinating time, January 1999. As I stepped off the flight from Heathrow it was as though I’d caught a time machine rather than British Airways flight 172 to JFK. It was absolutely incredible. I’d leapt forward 18 months in seven and a half hours and been hit by the dot-com tsunami. While the internet phenomenon was much talked about in Europe it hadn’t really happened. || In the US it was well under way and they were in the grip of dot-com madness. You turned on the radio or TV and virtually every ad was for a new dot-com venture. || And in a business presentation if you didn’t say ‘digital’ in the first 30 seconds you were dead.

We were told it was ‘the new economy’. Companies proudly announced they were working on ‘internet time’. What that actually meant was that they were running around in circles burning cash faster than they could fathom it all out. This was the time of the ‘new new’ and other such crackpot aphorisms. We had internet companies coming into BBH’s offices and pleading with us to take their business – client behaviour previously unheard of in the history of advertising.

I remember one bunch of messianic digital entrepreneurs, who had raised a cool $100 million to start some dot-com nonsense, coming in to ask us to take their account. No pleading! I had to get them to explain to me three times what the actual business was apart from having digital in its name. Naturally, we turned it down.

If we couldn’t understand it, how the hell were we supposed to advertise it?

The great phrase at the time was ‘it’s a land grab’. The thinking was that you had to get your name out there, establish a positioning for yourself and then negotiate your IPO (initial public offering). The so-called entrepeneurs following this route believed that in three years they would sell their company, make a fortune and move on. Of course, as in all these things, the very early adopters did. But by the time you’re reading about the opportunities in FastCompany or in the business press, it’s all over.

The trouble was that 99% of people didn’t know it was all over, and that 99% included the money men who were throwing dollars at the so-called new economy faster than the Federal Reserve could print it.

And it all came crashing down. The problem in an environment like that is that if you try to counsel caution, if you try to point out that gravity cannot be defied for ever, you’re branded a Luddite. || A collective insanity overtakes logic and God help you if you don’t recite the new mantra: digital is the only future. Fast isn’t fast enough. It’s all about clicks, forget the bricks. You’re only one click away from a disaster. We work 24/7.

Of course, those idiots did recite that mantra – they thought that within three years they would have made their fortune and be sitting on a Caribbean beach sipping a piña colada.

At BBH we were trying to build a company for the long term. A company that, hopefully, would add long-term value to our clients’ balance sheets.

At the peak of the dot-com lunacy there was a moment when a really quite good digital company, which I think had been set up in about 1996, called Razorfish, had a stock market value greater than that of Omnicom. How about that? You know when someone uses that phrase ‘the market is always right’? Well, let me tell you the market isn’t always right. Sometimes, it’s disastrously wrong. And when it’s wrong, by God it knows how to do it.

The ultimate example of this was how, in 2000, Time Warner decided they’d better get a grip of this digital future and merged with AOL, the then recently created on-line provider. Never has there been such disastrous and rapid failure. Here was a situation in which Time Warner, a collection of outstanding media brands built up over generations that nurtured real value and had genuine brand equity, were handing their company on a plate to a bunch of internet geeks who’d just got lucky. I remember my reaction at the time: this can’t be true, surely they’ve made a mistake? And did they make a mistake: within about a month of this so-called merger the market crashed and took most of the new digital players with them. Two years after the merger AOL Time Warner posted a loss of $99 million. I’m not sure who in Time Warner thinks that the merger with AOL was one of their greatest triumphs, but I bet there aren’t many. And I bet they’re no longer working for Time Warner.

Despite the madness of the time I’m not denying the contribution and the game-changing nature of the digital revolution because it certainly was a revolution. Never before had we seen such a rapid and seismic change in how we communicate – it is going to effect so much and, if understood, create such opportunities it would be madness to deny its presence, as it seems some people want to do. || But as with all revolutions, you must be sure to embrace its values and meanings with intelligence and common sense.

So what does the dot-com crash of 2000 teach us? It showed us that companies have to have a business plan that’s founded on genuine innovation, not the market madness of the ‘new new’. It showed us that gravity is a force that will finally make itself felt on the market.

It taught me, once again, not to let go of my basic principles. It also taught me that when someone is described as ‘an expert’, be very wary. Over the years I’ve learnt not to be in awe of anyone. And I mean anyone. You can respect people, you can admire their accomplishments, but never be in awe: it’s a dangerous condition to be in. || At the time of writing this book, the world is in the midst of a financial disaster. A disaster brought on us by people not understanding what was going on and being in awe of financial manipulators who assured those who should have known better that everything was all right. If someone utters a sentence to you such as, ‘This is a new paradigm, it’s not like it was before’, run a mile (or even several).

The dot-com crash helped destroy a number of agencies that had expanded on the back of the boom. They were companies that had overcommitted to the lunacy that had overtaken the market. || When the crash happened and the plug was pulled the effect was instantaneous – there was no gentle glide path back to reality. The streets were awash with casualties and I can assure you it wasn’t a pretty sight.

But, remember, I saw this all unfold during my time in the US, and in those kinds of situations the US takes the pain and moves on. Hard as that may seem, it is one of the qualities that makes the US a great country. When it comes to business it has very little sentimentality. Dead is dead to them. Mind you, in the current economic crisis, even the US is ditching some of those long-held beliefs: all I have to say is ‘General Motors’.

The problem right now for Western economies is how do you balance public good with commercial reality? No one’s quite worked that out yet. And I think there will be many more upsets before we understand where the equilibrium lies.

My two and a half years in the US (or rather New York) shot by. BBH established a foothold in this hugely complex market, won some great business and lost some. But we held on to our long-held belief – turning intelligence into magic – attracted some great staff and I believe have an exciting future. As I write this our current executive creative director, Kevin Roddy, has decided to leave. Life is nothing but interesting in our business. Getting the executive creative director appointment right is crucial. As I described in an earlier chapter, they represent the soul of the agency. Other people from other disciplines in the agency carry the flag of the agency, ensure that it’s a well-run company, provide the strategic and business acumen that a successful company needs, but ultimately it’s in the beliefs and passions of the creative director that the agency’s future resides.

What that person does, the demands they make on the agency, the creative leadership they provide, the quality of work they insist on, are all fundamental to the success of the business.

Without that philosophical, intuitive leadership an agency is nothing more than a marketing consultancy. There’s nothing wrong with marketing consultancies – they are stacked with intelligence – but what they don’t make is magic. || All the logic in the world doesn’t necessarily change a thing. Changing the way people feel and behave is the ultimate brand requirement and the ultimate responsibility of a creative idea. And that will remain true wherever we open an office.

The concept of the micro network is firmly established as an alternative way of creating big, bold, global ideas. You don’t need hundreds of offices with all the bureaucratic nightmares they bring. At last there’s genuine competition to major networks, and clients now have a choice. And choice is something I really approve of.