Okay, I’ll be perfectly blunt here: my favorite project I’ve ever worked on isn’t The Simpsons, The Critic, or any of those great animated films—it’s a little web series I created called Queer Duck (tag-line: He can’t even FLY straight!).

The show was born in 2000, in the great dot-com boom (and bust). My friends had started a company called Icebox, and it would feature a new online cartoon every day. The company was literally ahead of its time—these were the days of dial-up internet, and it took twenty minutes to download each three-minute cartoon.

Icebox offered no pay, just complete creative freedom, and most Simpsons writers jumped at that. Everyone got to write about topics that obsessed them: Jeff Martin did a series about Elvis and Jack Nicklaus solving mysteries; Dana Gould wrote about the Beach Boys’ domineering father Murry Wilson; and I dusted off a sketch I’d written in high school but never used: Hard Drinkin’ Lincoln. This featured a snockered Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre loudly heckling the actors; when Abe finally gets shot, the audience cheers.

Giant Abe Lincoln goes Godzilla on D.C. in Hard Drinkin’ Lincoln.

Hard Drinkin’ Lincoln was so popular, South Park ripped it off. That’s a bold claim, but here’s the case. I wrote an episode called “Abezilla” where the statue in the Lincoln Memorial comes to life and goes on a rampage in Washington, D.C. To kill him, the army creates a giant John Wilkes Booth. Crazy idea, right? Six months later, South Park (which shared a writer with Icebox) did the same story on its “Super Best Friends” episode. You can see both clips on YouTube—it’s pretty blatant. I don’t think it was an intentional theft: things like this happen when you crank out a whole episode in just a week, as South Park does. (It takes The Simpsons thirty-six weeks, minimum.) Anyway, imitation is the sincerest form of felony.

I followed up Hard-Drinkin’ Lincoln with a pet project called Queer Duck.

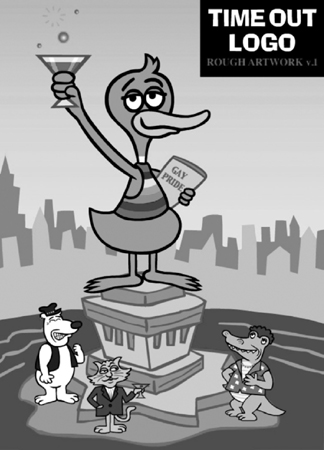

Queer Duck was a cartoon about a gay duck (surprise) and his gay animal pals Openly Gator, Bi-Polar Bear, Oscar Wildcat, Truman Coyote, Keangaru Reeves, Ricky Marlin, and the questionably tasteful HIV Possum and Patient Zebra.

Queer Duck made history as the first openly gay cartoon character. Now, I say openly gay because all cartoon characters are kind of gay: Bugs Bunny kisses Elmer Fudd on the mouth, Snagglepuss is theatrical, Daffy Duck has a lisp. Tweety Pie is Truman Capote.

The Pink Panther? C’mon.

Donald Duck is a character right out of gay porn: he wears a sailor suit but no pants.

And Woody Woodpecker’s name is a euphemism for Erectiony Erection Penis.

The Simpsons, of course, has its gay characters. But Marge’s sister Patty didn’t come out of the closet till five years after Queer Duck. Not that she surprised anyone. Homer’s reaction was “Patty’s gay? Here’s another bomb. I like beer!” As for Smithers, it took him twenty-seven years to finally admit he was gay. Just like my cousin Lee.

Queer Duck made it big—literally. He once made the cover of Time Out New York.

DAN CASTELLANETA ON ICEBOX

“I know Mike did things for the Internet: Hard Drinkin’ Lincoln and Queer Duck. That’s his real dark sense of humor. He just goes there. He doesn’t worry about the line. He finds out about the line after he says what he says. I was listening to a podcast he was doing, and Gilbert Gottfried said, ‘Lemme guess, you’re Jewish?’ And Mike says, ‘Yes. I made a living modeling for hate literature.’ That’s about as dark as you can go.”

As silly and raunchy as it is, I created Queer Duck as an act of conscience. I read two troubling articles in the year 2000: One reported that Colorado had barred homosexuals from teaching in public schools, the other that there were no gay characters on TV. None. This was before Glee and Will & Grace and Anderson Cooper and Rush Limbaugh. (“Oh, my God! He just outed Rush Limbaugh!”)

So I decided to redress these wrongs the only way I knew how: through cartoons.

The title came from a saying I used to hear as a kid (mostly about me): “That boy is a queer duck!” It didn’t imply homosexuality. A queer duck was just a weirdo. If the phrase had been “queer mole,” my cartoon would’ve been about a mole. (By the way, if you develop a queer mole, see a doctor.)

People ask, “How do you write Queer Duck? You’re not gay. You’re bi.”

I’m not gay. No, no. A thousand times no.

Three times, yes, but I was drunk. The first time.

Seriously, I’m not gay. But I am Jewish, which is kind of the same thing. We’ve both been oppressed for centuries. By our mothers.

In truth, I did have some concerns about the project at first. I even told the folks at Icebox that if this ended up being perceived as gay-bashing in any way, I’d pull the plug. I was doing this for gay people. I was giving them their own Bugs Bunny.

I even offered to turn the whole thing over to a gay cartoon writer, of which there are many. But Icebox said it would be fine, and just asked that we use a gay actor to voice Queer Duck.

The first person who came in to audition was Scott Thompson, the openly gay member of the hilarious Kids in the Hall comedy troupe and a mainstay of Garry Shandling’s The Larry Sanders Show.

I was very pleased to meet Scott . . . until he started berating me. Loudly. It embodied all my worst fears about the project: How insensitive the script was, how dare I presume to write it . . .

He chewed me out for twenty solid minutes, ending with a comment about my obviously Jewish appearance and asking how I would like it if someone were to do something like this about Jews. Oy vey.

And then . . . Scott Thompson proceeded to audition. He was even funny, but his reading sounded . . . hostile. (Two days later a friend saw Scott do stand-up—he was still angry, and his whole act was a tirade against this big-nosed guy doing a gay cartoon.)

Luckily for me, he was the last person to ever complain about Queer Duck. The next actor to audition was the buoyant and flamboyant Jim J. Bullock, who captured all the joy of the character. He got the part; it was an easy decision.

The supporting cast was mostly very talented people I’d worked with before: Tress MacNeille from The Simpsons, Maurice LaMarche and Nick Jameson from The Critic, and even a veteran of Homeboys in Outer Space: Kevin Michael Richardson.

The show was launched on October 11, 2000—National Coming Out Day—and immediately broke the dial-up internet. Viewership on Icebox.com spiked 400 percent, and the website crashed. Clearly the show filled a void. Two days later, a reporter called to interview me—from Germany!

I knew people were loving it, because there was a message board under the videos saying things like, “Oh, thank God! Finally a cartoon for me!” And when, every once in a while, we would receive a stupid comment like “I hate this gay shit!,” I just thought, All right! If I make a homophobe angry, that’s like making a homosexual happy!

One day, someone posted, “I wish this cartoon was around when I was thirteen. It would have made my life so much easier.” To this day, that’s the best review I ever got in my life.

Queer Duck became such a hit that it made the jump to the Showtime network (airing after Queer as Folk) and, unknown to me, was shown weekly on Britain’s Channel 4. In 2005, a poll of Channel 4 viewers named Queer Duck “One of the 100 Greatest Cartoons of All Time.” (Now, mind you, England is the world’s only exclusively gay country. Britain’s an island—it’s like a big gay cruise that doesn’t go anywhere.)

The response to Queer Duck has always been positive. I have a shelf of awards from gay groups. At least I think they’re awards. Many vibrate. GLAAD endorsed the series and even Howard Stern praised it. There’s the full spectrum right there: from GLAAD to Howard Stern.

“I’ve never gotten any email or heard of someone who was offended,” my amazingly talented director, Xeth Feinberg, said. “It seemed quite the opposite, actually. I’m surprised. I was expecting, ‘You’re insulting!’ But I never got feedback like that.”

The media opportunities and interviews rolled in, and, at first, I kept my mouth shut about being straight. In the beginning, when journalists would come over to interview me, I would hide my wedding pictures and lock my wife in the bedroom.

But then I came out of the closest (and let Denise out of the bedroom), and everyone was fine with my not being gay. When the New York Times wrote about it, they said, “Queer Duck was created by Mike Reiss . . . who is straight.” My father loved that—he never believed anything unless it was in the New York Times.

How popular was Queer Duck? Well, he made appearances in two Gay Pride parades. One in Los Angeles . . .

. . . and one in Springfield! In the 2002 Simpsons episode “Jaws Wired Shut,” a giant Queer Duck balloon flew over Springfield’s gay parade. Sadly, the scene was dropped, putting Queer Duck in that elite category of Celebrity Guests Cut from Simpsons Episodes for No Friggin’ Reason with the likes of SCTV’s brilliant Catherine O’Hara, John Cusack, John Turturro, and Aaron Sorkin.

In 2005, I made a Queer Duck movie for Paramount Pictures. Variety called it the best animated film of the year (in the same year Brad Bird’s Academy Award–winning Ratatouille came out). I showed the film in Germany and the audience laughed for seventy-five straight minutes, thereby doubling the total amount of time Germans have ever laughed.

You can still buy the movie on DVD from Amazon: you get the full film, the original Icebox shorts, and a making-of documentary.

Here’s what you don’t get:

I had a song in the movie during which all the gay animals are going to Disneyland. They sing “Let’s call Tom Cruise . . . What can we lose?” Paramount made me take that out, because Tom Cruise sues people who call him gay. All right. So I changed the line to, “Forget Tom Cruise . . . Call him gay, and he sues.” Paramount made me take that line out, too. So I told this story in the making-of documentary on the DVD. I said, “You can call anyone in this world gay except for Tom Cruise.” Paramount told me to take that out, too. When I asked why, they gave me a very Orwellian response:

“It’s against Paramount policy to discuss Paramount policy.”

Then the editor of the documentary had an idea—he obscured my lips and futzed the audio in the making-of doc so that I would say, “You can call anyone in this world gay except for [MURBLE BURBLE MURBLE].”

Paramount made me take that out, too. When I asked why, they said, “Because everyone knows you’re talking about Tom Cruise.”