I was recently reading about myself on IMDb, because, well, who else would? In a discussion thread titled “Mike Reiss Simpsons DVD Commentaries,” someone posted, “This guy sounds like he’s smiling all the time.”

That made me smile.

The next post read, “Yeah. It really gets on my nerves.”

I stopped smiling. But screw that guy. If I do smile a lot, it’s because I have the funnest job in the world. And because I have a beautiful wife who laughs at all my jokes. And because I think funnest is a word.

As a child I spent my first three years sitting in my playpen, never saying a word, just grinning like an idiot. My mother finally took me to a doctor, who told her, “The boy’s not brain-damaged. He’s just a little slow.”

Let’s chalk it up to the fact that I found life amusing, even at that age. I believe I was making up jokes for other babies, like “My daddy breastfeeded me.” (Hey, that’s not bad!) But to best understand my upbringing, you have to start with a joke. A joke about jokes:

A convict stands up in the prison mess hall and yells, “Seventy-three!” All the other inmates laugh. A new prisoner asks a guard what’s going on. The guard explains that the prison has one joke book and all the prisoners have memorized it. So instead of telling the joke, they just say the number of it. So the new prisoner stands up and yells, “Forty-eight!”

He gets no response and asks the guard why. The guard says to him, “Some guys know how to tell ’em, some guys don’t.”

My childhood was like this prison. I grew up in a house full of funny people who all loved jokes. We studied the four-hundred-page Joey Adams Joke Dictionary the way creepy families study the Bible. In fact, none of us had to tell a whole joke. We’d just mention a joke fragment, like “elephant-ear sandwich,” and everyone would laugh.*

I grew up in suburban Connecticut, the middle child of five kids. I have a brother who dabbled in stand-up comedy and a sister who wrote a joke book for speech therapists entitled How many speech-language pathologists does it take to change an audiologist? (It’s got five stars on Amazon.)

I was a pretty funny kid, too. One day, my mother heard that our handsome neighbor was marrying a hunchback. She asked, “Why would he do that?”

I said, “For good luck!” My father, normally a gentle man, smacked me in the head.

When I turned ten, I offered my Hungarian grandmother a slice of my birthday cake. She said, in her Yoda-like old-Jewish-lady syntax, “I only want next year you should give me a piece.”

I replied, “It’ll be stale by then.”

My father smacked me again. I began to think a joke was not truly good unless someone got hit for telling it.

My dad—a physician, a historian, a Phi Beta Kappa scholar—had a little bit of Homer Simpson in him. All dads do. You know, that mixture of anger, love, frustration, and more anger. Matt somehow found the character in his own father, Homer Groening, a documentary filmmaker who surfed and, ironically, had a full head of hair. (Sam Simon developed the character by drawing on his father, a man who seems to have little in common with Homer: he was a one-legged Jewish millionaire from Beverly Hills.)

My father’s mother may have been the funniest one in the family. I once asked her, after reading a Dixie cup riddle, “What’s worse than finding a worm in an apple?”

The cup’s answer was “Finding half a worm in an apple.”

My grandma Rosie’s answer? “Having someone shove an umbrella up your tuchis . . . and then open it.”

That was a better answer. And she came up with it so fast I thought it must have happened to her. Maybe it was the Cossacks. Maybe it was Grampa.

My other grandmother summed up our family best. Grandma Mickey was a South Carolina Jew (which is sort of like being a Baptist). After a family dinner one night she said, “Y’all make so many jokes!” Then, after a beat, she added: “Of course, none of them are worth a damn.”

Bristol, Connecticut, was a factory town that didn’t make things—we made the things that went into other things: brass, springs, and ball bearings. Ask anyone from Bristol what it’s like and they’ll say, “It’s like the town from The Deer Hunter.” I was never sure whether they meant Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, or Saigon.

But to me, Bristol represented Springfield. I’ve used so much of what I saw growing up as inspiration for The Simpsons. One of the very first scenes in the first episode of the show has Homer losing a game of Scrabble to his son and then throwing the whole game into the fireplace. My friend’s father did that. His name was Mr. Burns, by the way: Larry Burns. Years later, we did an episode where Monty Burns’s illegitimate son shows up (gloriously voiced by Rodney Dangerfield). By coincidence, the episode writer Ian Maxtone-Graham named the character Larry Burns. By an even greater coincidence, the artists designed a character that looked exactly like my friend’s father.

I told the real Larry Burns that we had named and designed the character just like him. He seemed totally unimpressed; nobody cared about show biz in Bristol. But after he died, I found out that my Larry Burns had bought up every Larry Burns Simpsons collectible figure in America. Perhaps he was building a clone army.

* * *

Like many comedy writers, I was inspired at a young age by The Dick Van Dyke Show. But I didn’t want to be Dick, handsome TV head writer, married to perky Mary Tyler Moore. I wanted to be Morey Amsterdam, the funny little guy on the show with the big blond wife, who cracked a lot of jokes at the office but didn’t do much work.

I have achieved all my childhood goals.

I loved movies, too, and was obsessed with the Marx Brothers. Nothing unique there. I was also fascinated by one of their writers, Al Boasberg, the great “script doctor.” It was said that Boasberg couldn’t write a great screenplay, but he was a genius at punching up other people’s work. Somehow I knew that’s what I was destined to do: not to be a writer but to be a rewriter. And when my parents’ friends asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I’d tell them script doctor.

“Oh, isn’t that cute,” they’d say. “He wants to be a doctor like his daddy.”

“Not a doctor, you country-fried idiots. A script doctor!” I’d mutter.

My writing career began in third grade. My teacher, Miss Borwerk, inspired the first poem I ever wrote:

I have a teacher named Miss Borwerk

Every day she gives me more work

All right, it’s not Emily Dickinson, but I was eight, for chrissake.

Whenever I came home from school, my mother would ask me what had happened in class that day. I’d say, “Nothin’.” And my mom said, “‘Nothing’ didn’t happen in school today! Tomorrow, when you come home, you better have something to tell me.”

Well, the next day nothing happened in school. When my mom asked me about my day, I panicked. In desperation I said, “Today a dog walked into class and Miss Borwerk threw it out the window.”

This seemed to satisfy her. So the next day, when nothing happened in school, I told her, “Today Miss Borwerk shot at the kids with paintballs.”

And the next day: “Miss Borwerk took off her underwear in front of the class.”

What I didn’t realize was that my mother believed these stories! She called the principal and said, “You have a teacher there named Miss Borwerk who’s a lunatic.”

When the principal reprimanded Miss Borwerk for taking off her underwear in class, Miss Borwerk protested, “I don’t wear underwear.” In turn, Miss Borwerk yelled at the principal, the principal yelled at my mother, and my mother should have yelled at me. Instead, she bought me a pencil box and a pad of paper, and said, “From now on, if you’re going to make up stories, write them down.”

I’ve been making up stories ever since . . .

Including that whole thing about Miss Borwerk. Never happened.

Psych!

The next three teacher stories are absolutely true, but, God, I wish they weren’t:

I had a teacher who liked my writing and told me to “follow my dreams.” A year later he was busted by the vice squad for following his dreams.

Another teacher told me, “Be what you always wanted to be.” I ran into him six years later in a Boston salad bar. He was my busboy. Maybe that was what he “always wanted to be.” But it raised an interesting philosophical question: how much do you tip the man who changed your life?

Answer: 17 percent.

Finally, there was Mrs. Defeo, my faculty adviser, who would hack my high school newspaper articles to pieces and change all my punchlines. This was excellent training for a career in television.

I once wrote a parody of our Student of the Month column. That month’s winner was a clearly psychotic kid who suggested we change the school colors to “black and darker black.”

Mrs. Defeo changed it to “black and blue.” “I can’t believe you missed the obvious joke!” she said.

“That’s why I didn’t do it!” I cried. “It’s the obvious joke!”

“You’ll never get a job writing for Cracked magazine with that attitude.”

Every night I’d pray to God that he’d punish Mrs. Defeo for her crimes against comedy.

A year later, she won a million dollars in the Connecticut lottery.

God always listens to my prayers, then does the exact opposite.

This was a rough-and-tumble public high school, and I was the only Jewish kid out of sixteen hundred students. And yet still, my mother said, “I only want you to date Jewish girls.”

I said, “Well, Mom, it looks like it’s going to have to be you.”

So I dated my mom for a few months. We got along fine, but her kids hated me.

* * *

In 1990, when I won my first Emmy for The Simpsons, I had my wife take a picture, which I sent to my hometown newspaper. Three days later, that photo of me in a tuxedo clutching an Emmy appeared on the front page of the local paper. The caption read LOCAL MAN CLAIMS TO WIN AWARD.

On to Harvard

If a giant sinkhole opened up and swallowed Harvard University, I’d think, Poor sinkhole. I spent four years at Harvard and I hated the place. I’m not alone: In a 2006 poll, the Boston Globe ranked schools in terms of fun and social life. Harvard came in fifth . . . from the bottom. Amazing. I couldn’t imagine four schools less fun than Harvard. But then I saw the list. The four schools ranked below us were:

- Guantanamo Tech

- Chernobyl Community College

- The University of California at Aleppo, and

- Cornell

At Harvard, the professors were dispassionate and their classes esoteric (though they did teach me the words “dispassionate” and “esoteric”). In four years there, I learned three things:

- How to open a champagne bottle

- How to make a bong out of an apple

- That mayonnaise is delicious (we didn’t have it in my house growing up)

I went into college knowing Latin and calculus. After four years, I’d forgotten them both. Blame the apple bong for that.

I tried to have fun at Harvard. In my freshman year, I did stand-up in the school talent show. After the performance, the judge told me, “You’re pretty funny.” So I married her. That’s the last time I ever did stand-up.

There was only one other comedian in the talent show, a guy named Paul, who bombed terribly:

PAUL: Coming up next, survivors of The Texas Chain saw Massacre will form a human pyramid.

AUDIENCE: Booo!

After the show, I told him, “Paul, maybe comedy’s not your thing.” He took my advice, went into drama, and created the hit medical show House. Paul is now worth a zillion dollars; me, I still steal Splendas from KFC.

In short, there are just two things I took from Harvard that I treasure to this day: my beautiful wife, Denise, and a large pile of library books. They’re both stacked in the bedroom.

AUDIENCE: Booo!

My wife and I visit the Harvard Lampoon Building. The building was designed by Lampoon founder Edmund March Wheelwright; it’s said he built it either just before or right after he went mad. Funds for the project came from Lampoon alum William Randolph Hearst.

The Harvard Lampoon

Why did I even go to Harvard? I only knew two facts about the place before enrolling:

- Thurston Howell III, the clueless millionaire from Gilligan’s Island, went there. (My freshman roommate was Thurston Howell IV.)

- It had a humor magazine, the Harvard Lampoon. I wanted to be part of it.

Back in the 1970s the Lampoon was not known as an incubator for comedy writers. In fact, for its first century of existence, it produced only four famous graduates: Robert Benchley, George Plimpton, John Updike, and Fred Gwynne, the guy who played Herman Munster (really!). In comedy terms, that list of famous alumni consists of a funny guy, a wry guy, a serious guy, and Frankenstein.

The legacy of the Lampoon changed when a member named Jim Downey got hired on the first season of Saturday Night Live (and stayed there for four decades). Jim opened the door to two more Lampoon friends, who let in some more friends, and by the end of the millennium, there were dozens of Lampooners in movie and TV comedy. Jim Downey was like a funny Patient Zero. There are so many of us working in Hollywood that we’re called the Lampoon Mafia, which is kind of an insult . . . to the Mafia. At least they have a code of honor.

At the 2016 Emmys, four of the six nominated comedy series were run by Lampoon alums (Veep, Silicon Valley, Master of None, Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt), and the last two series were created by Lampooners as well. In the best comedy script category, four of the five nominees, including the winner, were written by our graduates.

Lampoon people are everywhere, working on, sometimes running, every late-night show (Fallon, Kimmel, Corden, Colbert, The Daily Show, and, obviously, Conan). They’ve made up 30 percent or more of the writers of the seminal comedies of the recent past: Seinfeld, SNL, Letterman, and The Office. And, in animation, you’ll find them working for Bob’s Burgers, Futurama, Family Guy, and, of course, The Simpsons. Our original writing staff, hired by Stanford grad Sam Simon, was half Lampooners. Since then, about forty more Harvard grads have worked on the show, including eleven Lampoon presidents.

But how does a magazine founded in the nineteenth century prepare writers for a career in TV? Because, by a pure accident of history, the competition to get on the Lampoon operates exactly like the TV business. Students competing (called “compers”) are expected to turn in six humorous articles in eight weeks, which teaches you to hit deadlines and to be prolific, two fundamental skills in television. Like in TV, the competition is brutal—every year, about a hundred writers try out, and only seven get chosen. And finally, just like in TV, the process is completely unfair—very few compers get elected their first time. I had to go through the process twice; Dave Mandel, the brilliant showrunner who year after year takes Veep to an Outstanding Comedy Series Emmy, went through it five times. Comedy legend Al Franken was turned down by the magazine, which shows it’s easier to get elected to (and subsequently booted out of) the U.S. Senate than to get on the Harvard Lampoon. To join the magazine, you need to be self-confident, dedicated, and a little bit delusional. Just like a TV writer.

Once you get on a staff, whether it’s the Lampoon or a sitcom, you’re doing the same thing: sitting on your ass in a room full of funny people, eating crap food. In both cases, you shoot the breeze all day (and long into the night), making jokes and mastering the skill of fast, funny banter.

The one paradox is that while Lampooners write great TV, their magazine sucks. I’ve never understood why, but the Harvard Lampoon is bad today, it was bad when I was president, and it was bad when Robert Benchley ran it. For the half century before him, it was bad and racist. You can read all about it in my next book, Fifty Years of Laughter: A Hundred and Forty Years of the Harvard Lampoon.

CONAN O’BRIEN’S HARVARD LAMPOON DINNER

“Mike and Al showed up at the Lampoon and we had a big dinner for them. It was not even my idea, but I think the chef thought it would be really funny that since I was the president of the Lampoon, they would just serve potatoes for dinner. That’s all there was: potatoes. And I remember Al Jean and Mike Reiss being really pissed because they had legitimately come here for a meal. We treated the meal as a funny conceptual thing, and they were like, ‘Where’s my fucking lobster?’ We were like, ‘Well, no, this is the comedy, you see?’ And they were like, ‘No, we’re adults and this is supposed to be a meal, and we’re hungry.’ So they didn’t forgive me for that for a while. For years afterward, Mike Reiss was mad about that potato dinner. I think he got back at me, though, because I went to his apartment in New York a few years ago, and he served me some Manischewitz out of a box that I think had been sitting in the sun since the Ford administration. So, he got me back.”

(AUTHOR’S NOTE: I thought that was good wine.)

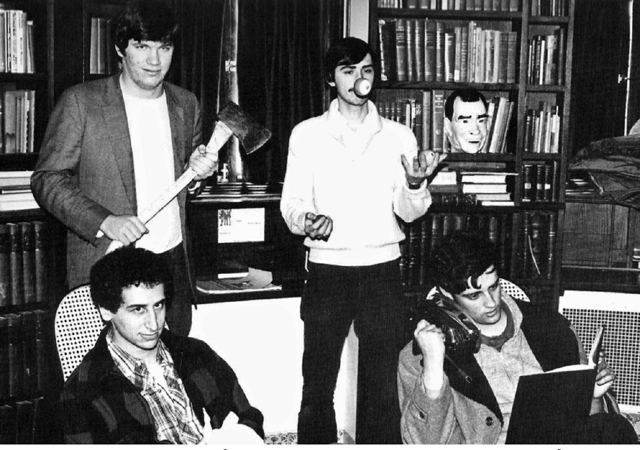

Harvard Lampoon, 1981. (Left to right:) That’s me and Al Jean in the front. Behind us, future attorney Ted Phillips and future Futurama writer Pat Verrone.

In 1982, I appeared in the Harvard Lampoon’s People magazine parody—in triplicate. I’m playing the Bother Brothers, who annoy people for a living. The caricature behind me is by future Simpsons writer Jeff Martin.