By the Dawn’s Early Light

When Maryland lawyer Francis Scott Key took up writing poetry as a hobby, he had no idea that it would one day make him famous.

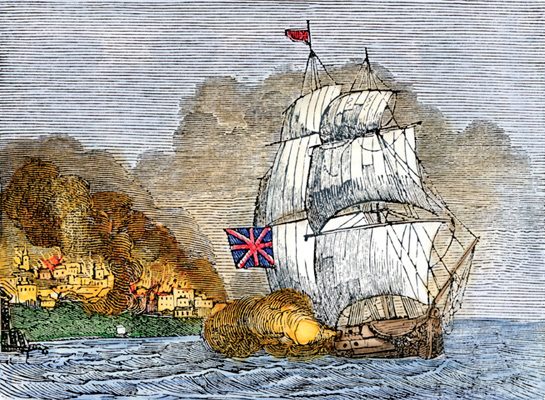

The War of 1812 was already two years old and escalating in Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay area in September 1814 when Key received word of a friend’s arrest. Dr. William Beanes was being held prisoner on a British ship in the bay. The British, having just burned Washington, D.C., were preparing to attack Baltimore by water.

After receiving permission from President James Madison to try to obtain Beanes’s release, Key and another associate, John Skinner, headed out in a small vessel flying a flag of truce on September 5.

After some debate, the British admiral consented to release Beanes. Fearing that the three men had heard and seen too much of the plans for attacking Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, however, the admiral ordered the men to remain on a U.S. prisoner-exchange boat at the rear of the British fleet until after the battle.

On September 13, the British began a bombardment of Fort McHenry. An anxious Key paced the ship’s deck all night. When dawn broke, thick smoke and haze surrounded the area. Key strained to see which country’s flag flew over the fort. Suddenly, the mist lifted, and Key rejoiced as he saw the beloved Stars and Stripes unfurl in the breeze. He pulled an unfinished letter from his pocket and jotted down a verse expressing his feelings. He finished the four-verse poem after returning to Baltimore later that day.

The following day, Key’s brother-in-law, Judge Joseph Nicholson, had the poem, titled “The Defense of Fort McHenry,” printed on handbills and distributed throughout Baltimore. Immediately popular, the words were set to the tune of a popular English drinking song.

Key’s patriotic gesture provided the country with two important American symbols: a national song and pride in the national flag. Prior to this, the flag was not so closely connected to the identity of the nation. Key’s words helped many Americans see the flag as an important national symbol. By 1904, the U.S. Navy played Key’s song at all ceremonial occasions, and in 1916, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed it the national anthem for all armed forces in World War I (1914–1918). “The Star-Spangled Banner” became the country’s official national anthem in 1931.

And what about the flag that inspired the song? The commander of Fort McHenry, Lieutenant Colonel George Armistead, had commissioned Baltimore seamstress Mary Pickersgill to make it. He requested that the flag be “so large that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance.” Pickersgill and her assistants completed the enormous 30-by-42-foot flag with 15 stars and 15 stripes in about six weeks. After the War of 1812, the flag became a family keepsake owned by the Armistead family.

In 1912, Armistead’s grandson, recognizing its national significance, gifted the flag to the Smithsonian Institution. For many years, it hung in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History on the Mall in Washington, D.C., covering an entire wall. But in 1998, museum staff removed it from display in order to restore it. Carefully packaged, the fragile flag was sent to a preservation lab, where it underwent several years of painstaking cleaning, repair, and reinforcement. For a fascinating look at how conservators cared for this national treasure, go to americanhistory.si.edu/starspangledbanner/preservation-project.aspx. Today, the Star-Spangled Banner is once again on display at the National Museum of American History. It lies at a 10-degree angle in a specially designed room that protects it from being damaged by sunlight.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” (verse 1 of 4)

O! say can you see by the dawn’s early light

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming?

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight,

O’er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming?

And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.

O! say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

Hear America Sing

America’s most famous symbolic tune is its national anthem, but several other pieces of music are well known for how they capture the country’s history at the time they became popular.

“Yankee Doodle” started out as a British song that mocked the shabby American colonists in the decades before the Revolutionary War (1775–1783). A “doodle” was a nickname for a fool, and the British used the song to poke fun at the rough American soldiers. The patriots, however, claimed the song for themselves and it became an unofficial national anthem. Americans even made up new verses that poked fun at the British.

In 1893, poet and teacher Katharine Lee Bates took a train trip across the country. Along the way she saw many amazing things—the white buildings of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Illinois, the wheat fields of Kansas, and the view from the top of Colorado’s Pikes Peak. These images of America inspired Bates to write a poem called “Pikes Peak.” Church organist Samuel A. Ward set the poem to music. In 1910, the words and music appeared together as the song, “America the Beautiful.” Today, it is one of America’s best-loved patriotic songs.

A song that captures the essence of America in the mid-1900s for many people is folksinger Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land.” Guthrie wrote the song, including some political verses, in 1940 in response to Irving Berlin’s song “God Bless America,” which Guthrie found unrealistic. Published in 1951, Guthrie’s song offers a more personal and individual connection to the land and the places in America:

“This land is your land, this land is my land,

From California to the New York Island,

From the Redwood Forest to the Gulf Stream waters,

This land was made for you and me.”