A Capitol With Class

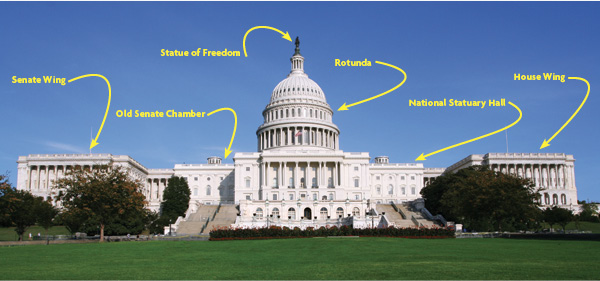

With its beautiful domed Rotunda, the U.S. Capitol is one of the most recognizable buildings in the world. And as the place where the members of Congress have debated and passed our nation’s laws for more than two centuries, it is an important symbol of the U.S. government. But in order to keep up with the growth of the country, the Capitol has seen many changes over the years.

In January 1791, French engineer Pierre L’Enfant was asked to design America’s new capital city. L’Enfant submitted his idea to commissioners for a grand vista about a mile long. At one end, the city’s “Congress House” would be located. The U.S. government decided to hold a contest to find the best design for the new country’s Capitol. The winner of the $500 prize was a physician named William Thornton. He presented a classical domed building with two identical wings extending on either side.

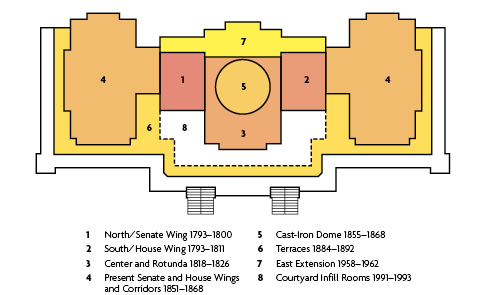

Construction began in 1793, when President George Washington used a silver trowel to lay the cornerstone on Jenkins Hill (known today as Capitol Hill). It was hoped that Congress, which had been meeting temporarily in Philadelphia, could move in by the turn of the century.

By 1796, though, construction was behind schedule. Lawmakers decided to focus on completing the north wing, but parts of that still remained unfinished in 1800. Both houses of Congress, the Supreme Court, the District of Columbia courts, and the Library of Congress moved in anyway.

Congress authorized more money for the Capitol in 1803 and appointed architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe to oversee construction. He had the south wing finished by 1811, but by then, the north wing was in need of repair. During the War of 1812 (which lasted until 1815), Congress refused to worry about the project, and a frustrated Latrobe resigned in 1813.

In August 1814, an invading British force set fire to parts of the city, including the Capitol. A timely rainstorm saved the burning city from complete destruction, but Congress was forced to meet for a time in a cramped building. Congress begged

the efficient Latrobe to return, which he did—until he resigned again in 1817. His replacement, Charles Bulfinch, designed a beautiful copper-covered dome for the central section of the Capitol. The building finally was completed in 1826, more than 30 years after construction began. By then, however, the United States had expanded westward, so Congress needed more space.

Another competition to expand the Capitol in 1850 resulted in a five-way tie. President Millard Fillmore chose Thomas U. Walter to supervise construction of two larger wings. Walter also came up with a design for a huge cast-iron dome. In 1855, Congress voted to replace Bulfinch’s dome with Walter’s grand design.

Though the outbreak of the Civil War (1861–1865) briefly interrupted construction, President Abraham Lincoln refused to stop the project and was inaugurated in 1861 beneath the half-completed dome. In December 1863, the final section of the 19-foot-tall Statue of Freedom was hoisted into place. Five years later, the building, with its great domed Rotunda that is so familiar today, was completed.

The Capitol, however, still required renovations, repairs, and updates. To deal with overcrowding, government offices and departments started to move out. In 1897, the Library of Congress went into the first of its three new buildings. The first of seven separate buildings with office space for the House of Representatives and the Senate were constructed nearby. The Supreme Court moved into its own building in 1935. Most recently, a new underground Capitol Visitor Center was completed. Today that area of Washington, D.C., is called the Capitol Complex, or Capitol Hill.

In addition to being the headquarters of Congress, the Capitol displays an impressive collection of American art, from murals and paintings to sculptures and hand-painted corridors. The Founding Fathers considered the legislative branch to be the most important branch of the federal government. Any visitor to the Capitol today can see how—inside and out—it holds its place as one of the most important symbols of both our government and our nation.

Growth of the Capitol

Uncle Sam

Illustrations of Uncle Sam, in his red-and-white-striped pants, top hat, and blue coat, are used to represent the U.S. government, but “Uncle Sam” actually traces his roots to a real person. An honest and patriotic man, Samuel Wilson was in the meatpacking business in Troy, New York. During the War of 1812, he provided barrels of meat for the U.S. Army. The barrels were marked with “U.S.” for United States, but soon his workers joked that the initials really stood for “Uncle Sam” Wilson.

In time, “Uncle Sam” was adopted as a personification of the U.S. government. The famous political cartoonist, Thomas Nast, was the first to draw Uncle Sam with whiskers in 1869. But it was artist J.M. Flagg who gave Uncle Sam his now-familiar tall, thin, and serious look. Flagg’s famous World War I (1914–1918) enlistment poster shows Uncle Sam pointing a finger and saying, “I Want You for U.S. Army.”