The Real National Treasures

A long line snakes in front of the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C. What’s all the excitement about? you wonder. In the building’s Rotunda, people slowly make their way past three display cases. They stop for a few moments in awe and respect.

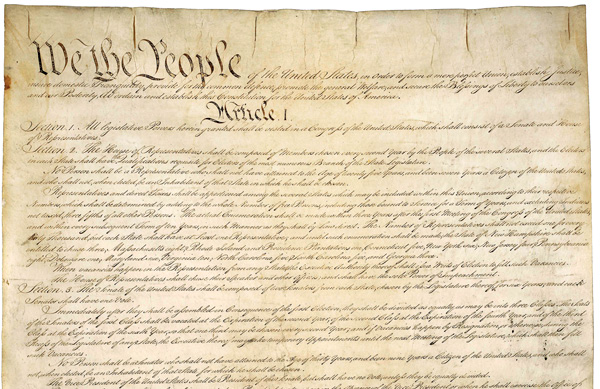

Every year, more than one million people visit the National Archives to see what is in those cases. On display in specially designed argon-filled glass cases are the original Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Bill of Rights.

Together, these three historic documents are referred to as the Charters of Freedom. Many visitors to the National Archives say that being able to see these famous documents up close, knowing that our nation’s Founders actually touched and handled them, is a magical feeling.

But these famous symbols of U.S. government and democracy weren’t always so accessible. During the American Revolution and until 1789, the Declaration went where the Congress went. It traveled to Pennsylvania, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York. The Declaration probably spent these years rolled up, like other parchment documents of the era.

After the Constitutional Convention adjourned in 1787, Major William Jackson, the convention’s secretary, delivered the original signed copy of the Constitution to the secretary of the Continental Congress. In 1789, the State Department—which would soon move with the federal government from New York to Philadelphia and then to Washington, D.C.—became responsible for all the records and documents that had been held in the office of the Congress’s secretary. Among these were the original Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

On one occasion, these pieces of history narrowly escaped destruction. During the War of 1812, while the British were advancing on Washington in 1814, a clerk at the State Department took the time to stuff the Declaration and the Constitution, as well as several other important government records, into linen bags before fleeing the city with them. The documents then were carted off by wagon to nearby Leesburg, Virginia. The British later set fire to many sections of the capital city.

Over the next century, the one-page Declaration experienced deterioration from exposure to sunlight as it was put on display at various times and in various places. The ink began to noticeably fade. By 1894, it was decided that the document was no longer safe to exhibit. Meanwhile, the other documents led a quieter existence in the custody of the State Department.

In 1921, President Warren G. Harding asked Congress to transfer the documents to the Library of Congress for preservation and exhibition to “the patriotic public.” But their final stop came on December 13, 1952. The documents were legally transferred and moved under military escort to the National Archives Building. Workers carefully placed them in helium-filled cases in the Rotunda’s Exhibition Hall. When not on display, they were lowered into a vault below the cases.

In 2001, the Archives began a major renovation of the Rotunda. At the same time, the badly faded Declaration underwent conservation treatment. When rededicated in 2003, the Charters of Freedom had new, 21st-century, state-of-the-art reencasements. The new exhibit space will preserve and protect the Charters so that future generations of Americans can experience that feeling of awe as they come face to face with our nation’s founding documents.

About the Charters

The Declaration, signed on August 2, 1776, notified the world that the 13 Colonies were separating from Great Britain in order to protect “certain unalienable Rights, [and] that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” The Constitution, signed on September 17, 1787, and ratified on June 21, 1788, created a new, more specific framework for government that would offer “a more perfect union” than the failed Articles of Confederation. The Bill of Rights, ratified and added as 10 amendments to the Constitution on December 15, 1791, protected specific individual rights of citizens, such as freedom of speech and freedom of religion.