CHAPTER |

3 |

How to Practice Yin Yoga |

All tissues of the body must undergo stress to stay healthy. If we do not exercise our heart it will degenerate, if we do not exercise our muscles they will atrophy, if we do not bend our joints they will become stiff and painful. Astronauts living in a weightless environment for a few weeks will lose up to 18 percent of their bone density and 30 percent of their muscular strength. Tissues must be stressed on a regular basis to stay healthy, even if only by gravity. In colloquial English, it is “use it or lose it.”

All forms of exercise can be classified as yin or yang based on the tissues they target. Exercises that focus on muscles and blood are yang, exercises that focus on connective tissue are yin. Yang exercise is characterized by rhythm and repetition, yin exercise is characterized by gentle traction.

The long-term goal of weight training is to make the muscles stronger, but immediately after a vigorous training session the muscles are weak and exhausted. Weightlifters boast about how much they can exhaust their muscles with expressions such as “My legs were so wasted after squats I could hardly walk to my car.” So the short-term effect of weight training is muscle weakness, but after weeks and months of regular training and rest the muscles get stronger.

The long-term goal of aerobic conditioning is lower blood pressure and heart rate but the goal in an aerobics class is to raise one’s heart rate and keep it raised for several minutes. Even after class it takes an hour or more for the blood pressure and heart rate to return to normal, but after weeks and months of regular training the resting blood pressure and heart rate drop to lower levels that more than compensate for the higher rates during exercise.

This is the normal training effect: the short-term effects of exercise are the opposite of the long-term effects. The same is true of yin yoga practice. One of the long-term goals of a yin practice are strong, flexible joints. Immediately following a long yin pose, however, our joints can feel fragile and vulnerable. This feeling is brief and should pass after a minute or two.

Dense connective tissues do not respond to rhythmic stresses the way muscles do. Connective tissues resist brief stresses but slowly change when a moderate stress is maintained for three-to-five minutes. To explain why, we will revisit our analogy of connective tissue as a sponge. To make the analogy more accurate, we must imagine the sponges of our bodies completely soaked with fluids that behave like butter. When the butter is solid the sponge is stiff and hard to bend, but when the butter is melted it is easy to stretch and twist the sponge. This change from stiff butter to melted butter is called a “phase change.” Holding a stress on connective tissue for several minutes creates a phase change in its fluids, which results in a lengthening of the tissue and a feeling of ease. This phase change also allows a greater movement of chi through the tissues, which is both pleasurable and promotes healing.

Someone new to yoga will probably experience a phase change during a posture but the physical lengthening might not be very profound. In other words, they will experience a pleasant energetic release even if they do not sink much deeper into the pose. But with persistent practice the fibers of connective tissue will grow and realign to allow for a greater range of motion as well.

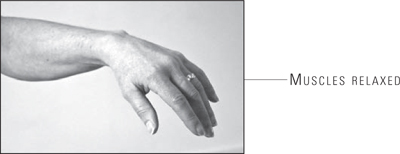

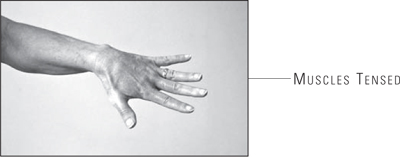

To stress the connective tissue around a joint the muscles must be relaxed. If the muscles are tense then the connective tissue doesn’t take the stress. You can demonstrate this for yourself by gently pulling on the middle finger of your left hand. When the left hand is relaxed you can feel the connective tissue of the finger joint stretching at the joint nearest the palm. When the fingers of the left hand are tensed and extended you can feel the muscles resist the pull, but the connective tissue is not being stretched.

The stretching of the knuckle may seem a trivial example but the same principle applies to the knees, hips, and spine: the muscles in these areas must be relaxed if the connective tissue is to be stressed when doing a pose.

Note that it is not possible or even desirable for all the muscles of the body to be relaxed when doing yin poses, but the muscles in the target area must be relaxed. For example, in a forward bend you may want to gently pull with your arms or contract your abdomen to increase the stress along the spine. But the muscles along the spine must be relaxed or the connective tissue will not be stretched.

There are three layers to a joint: the bones, the connective tissue, and the muscles that move the bones. When the muscles are relaxed, the bones can be pulled apart and the connective tissue is stretched. When the muscles are tensed, the bones are pulled tightly together and the connective tissue is not stretched.

All things have a yin-yang to them, even our attitude, and one way to illustrate the contrast is by comparing the attitude of a naturalist with that of an engineer. An engineer has a yang attitude, an engineer wants to change things, she wants to tear an old building down or build a new one up, she wants to dam the river or dredge the canal. Her yang attitude is to alter and change what she sees.

A naturalist has a yin attitude. A naturalist wants to know how plants or animals behave without trying to influence them. A naturalist with an interest in butterflies has to go to where the butterflies are and then sit and patiently wait for them to do what butterflies do. A naturalist cannot make butterflies fly or mate or lay eggs, he can only wait and observe. His yin attitude is to try to understand what he is watching.

When practicing yin yoga it is best to have a yin attitude. Do not be anxious or aggressive and force your body into the poses. Make a modest effort to approximate the pose as best you can, and then patiently wait. The power of yin yoga is time, not effort. It takes time for our connective tissues to slowly respond to a gentle stress, it cannot be rushed. Learning to patiently wait calms the mind and develops the necessary attitude for meditation practices.

Modern culture appreciates the strength of the yang attitude to “go for it,” but there is no end to our desires. To be truly happy we must also cultivate the yin qualities of patience, gratitude, and contentment.

There is no such thing as a pure yin or a pure yang attitude, just as there is no such thing as a pure yin or pure yang yoga practice. These two aspects always coexist. Yin or yang might be dominant in expression but the other is always present.

When practicing a yin pose such as a forward bend, we want to be as relaxed as possible. But if we completely relax every muscle in our body then we might actually fall out of the pose. Some muscular effort is required to balance ourselves in a pose and to maintain the gentle traction, so yang effort is present even in yin yoga poses.

The same can be said of our attitude during yin yoga. It is yin to passively observe the sensations that arise, but it is yang to make the effort needed to maintain the pose.

Many beginners unconsciously hold their breath when practicing yoga postures, so teachers often advise them to breathe a certain way to keep them focused yet relaxed. When practicing yin yoga my general advice is to breathe normally. Each posture affects our breathing in a different way. It may be that some postures were specifically designed to alter the breath and thereby alter the perceptions in meditation. To force yourself to breathe the same way in every pose is a yang attitude, and it obliterates the possibility of assessing what the posture does to your natural respiration.

There are times in yin practice when I experiment and hold my breath for a few moments or breathe rhythmically for a little while, but the majority of the time I just passively observe the effect each pose has on my natural respiration.

After practicing a pose for several minutes it is a good idea to relax on your back and feel the rebound. Poses temporarily block chi and blood from flowing in some areas and redirect it toward other areas. The rebound is what we feel after we release the pose and relax on our backs.

The physical sensations of stretching muscles and joints usually dominates our awareness when we are holding a pose, but when we relax on our backs we can calmly focus on the sensations of chi. This can manifest either as a sense of pressure dispersing away from an area and spreading throughout the body or as a more specific feeling of energy in our spine or legs. After a minute or so the sensations morph and change into a general feeling of peaceful calmness that is not centered in any particular area.

Cultivating awareness of chi is an important part of yoga practice because chi is the thread that ties all three bodies together. Learning to feel chi in the physical body is a first step to objectively experiencing the emotions of the astral body and the thoughts of the causal body.

The short-term effects of yin practice are the opposite of the long-term. The feeling immediately following a long yin pose is a sense of fragility and vulnerability. Sometimes you can feel a rebounding contraction building up that seems as if it will grow into a painful spasm, but if you stay calm during this process you will find the dreaded painful spasm does not come, and the rebounding wave will reach a crescendo and then subside. This can be a life-changing experience for many people. I have heard from many students who suffered chronic pain for years but healed themselves by learning how to relax in yin yoga.

Some students become alarmed at these sensations and immediately roll to their side or hug their knees or do some other simple counter pose. It is certainly permissible to do counter stretches after a pose, but every once in a while resolve to lie on your back and calmly observe the rebound without reacting.

Some students say that they “Do not feel anything” when practicing asana or when they are relaxing on their back. This is not possible. There are always sensations arising from our bodies, and we only have to focus our attention to experience them. Our chi will move to wherever we place our awareness. It is also true that wherever our chi moves it will bring our awareness with it.

Try this exercise: Sit comfortably and focus on your nose. Is it warm? Does it itch? Is there a pulse? Is the inhalation in the top of the nostril, or the bottom? Is one nostril more open than the other? Exercises like this are endless and demonstrate the impossibility of being without feeling—we need only direct our awareness to it.

If a student insists he is not feeling something, we can only surmise that he is not feeling what he imagined chi should feel like. It is a misconception to think chi only flows through the meridians depicted on a chart. Chi flows into every cell of the body. The meridians depicted on acupuncture charts are just the surface meridians accessible by needles. There are larger, deeper meridians referred to as “reservoirs of chi.” These are the source of the surface meridians. Chi circulates from these deeper meridians into the surface meridians and then back again. The movement of chi in these deeper meridians is felt in the bones, muscles, and organs.

I am not dissuading students from trying to feel specific meridian channels but I am encouraging them not to overlook the more obvious “physical” sensations of chi movement throughout the body and the pleasant calmness it brings.

One hundred years ago the American philosopher William James suggested an experiment to illustrate the mind-body connection: Relax on your back and become calm. Once you have succeeded in relaxing, then try to make yourself angry without tensing or altering your body in any way. In other words, try to become angry without tensing your muscles, changing your breathing, clenching your teeth, raising your blood pressure or your heart rate, or manifesting any other physical change. Impossible! Every thought, every emotion puts its imprint on our physical being.

In our highly intellectual, head-oriented world many of us are physically stressed and do not know it. We imagine that by masking our emotions they are not affecting us. But masking suppresses only the crudest outward display of our emotions—our bodies are still taking a beating. If we were more aware of the physical toll of our inner life, we might take more precautions against undesirable mental states.

Learning to relax in poses like the Pentacle helps us to identify and release tensions that are deep within us, not just in the skeletal muscles. Tension in the eyes, jaw, heart, diaphragm, and stomach can be isolated and relaxed. This healthy habit helps us to dissolve the negative tensions that accumulate in our bodies. This is a valuable skill in our heart attack-prone society.

Dr. Motoyama has demonstrated that the meridian system and the nervous system are yin-yang to each other. This means that if the energy in one system increases, the energy in the other system decreases. Yin yoga amplifies chi energy and reduces nervous energy; therefore a common reaction after doing yin poses is to desire to just lie still and not move. When deeply relaxed, the effort it takes to move the limbs just doesn’t seem worth it.

This inhibition of movement is a desirable state and it is a perfect prelude to meditation. Many people are so nervous they literally cannot sit still for several minutes. A yin practice can change this. If you find yourself wanting to extend your rest phases during your practice, don’t fight it. Recognize and enjoy it, and this will develop your ability to recreate the peaceful state of immobilizing inner calm. When you can do this you are nearly over the first hurdle of meditation, which is sitting upright and relaxed for extended periods of time.