CHAPTER |

6 |

Sitting |

The practice of yin yoga culminates in the ability to comfortably sit in an upright posture for an extended period of time. Until we can do this, our ability to go deep in meditation will be hindered. When most people try to sit they soon become distracted by discomfort in their hips, knees or lower spine. Acupuncture theory says this discomfort is due to the stagnation of chi and blood. The connective tissue in these areas is so tight that the pressure of the posture soon chokes off the flow of chi. A deep yin practice makes these joints more flexible and you will be able to sit much longer before chi stagnation becomes a distraction.

The ancient texts on yoga say that proper sitting can heal many diseases. In my own experience this seems possible. My students and I, when sitting for a half-hour or more, have experienced subtle adjustments occurring along the spine. These adjustments or “cracks” along the spine are usually preceded by a slow build-up of pressure at one or two points accompanied by muscle tension over a broader area. When the tension reaches a certain point, a slight twist or adjustment of the body causes the vertebrae and ribs to move with a “cracking” sound and this is accompanied with a wonderful sense of relief or fullness. This whole process might recur once or twice if the Yogi sits long enough. I intuit that these spinal adjustments free the flow of chi to all the body and affect our long — term health.

All of us come to a practice of sitting with some history of injury or neglect of our spines, and learning to sit is going to bring uncomfortable sensations due to spinal misalignments and blocked chi flow. The practice of yin yoga helps minimize these symptoms, but even the most flexible and healthy of us will suffer through some physical discomfort as the body slowly readjusts itself. These symptoms are an inevitable part of spiritual discipline and sometimes recur for even veteran meditators. I mention this to encourage those who labor under the illusion that they are the only ones who find something so “simple” as sitting a difficult thing to do. It is not for nothing that over two thousand years ago Patanjali, the great systematizer of Yoga philosophy, listed learning to sit as one of the essential skills a Yogi must develop.

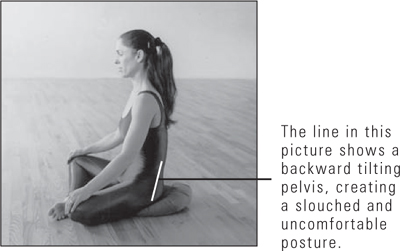

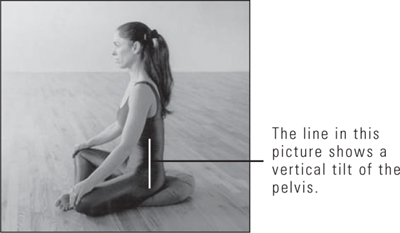

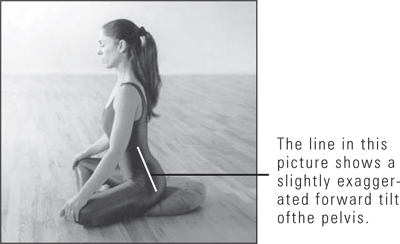

All sitting postures aim at one thing — a comfortable, upright posture. Straining or slouching in a pose creates uncomfortable pressure points and this interferes with the flow of chi up and down the spine. The most fundamental factor in achieving a comfortable sitting posture is the tilt of the pelvis. The upper body takes care of itself if the pelvis is properly adjusted.

When a person tires while sitting, the top of the pelvis is unconsciously tilted backward. As a result the whole body slouches, the flow of chi is reduced, and in a matter of minutes the would-be meditator gives up. When this person “straightens up,” they are tilting the top of the pelvis forward. It is this vertical or slightly forward tilt of the pelvis that establishes a comfortable meditation posture.

Siddhasana is the most popular of the meditation postures. In Sanskrit it means “the perfected pose.” One foot is pulled in with the heel as close as comfortable to the genitals. The other foot is pulled in front of the first. You might want to occasionally alter the foot positions.

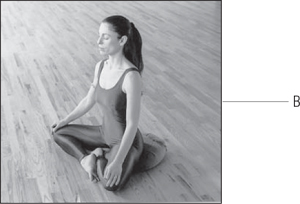

The hands should be placed so that the arms and shoulders can rest comfortably. You might rest hands folded together on your lap or on the knees with palms up or palms down. I sometimes assume an asymmetrical position with one hand on my lap and the other palm down on my knee (A).

The key to siddhasana is that the hip joints should be elevated at least as high as the knees, if not higher. If the hips are lower than the knees, then the top of the pelvis will be tilted backwards and this will quickly fatigue the muscles of the lower spine, causing discomfort. Sitting on the edge of a pillow or rolled blanket makes all the difference in being able to sit comfortably as this raises the hips above the knees (B).

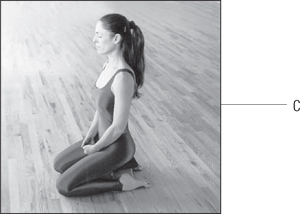

Seiza is commonly called “sitting Japanese style.” It is much like the beginning phases of Saddle except the knees are kept close. The buttocks rest on the heels and the hands rest folded on your lap (A). Very flexible people sometimes sit between their feet rather than on them (B). Either variation is made easier by sitting on a small cushion or folded blanket. This relieves the pressure on the back of the knees and calves. Many bookstores now sell “seiza benches” or “meditation benches” that work much like a cushion (C).

The most accessible posture for Westerners is sitting on the edge of a chair with the spine straight and not touching the back of the chair. This is the posture Paramahansa Yogananda taught to his Western students.