Chapter 2

1861

After South Carolina seceded on December 20, Major Robert Anderson, in command of the federal garrison in Charleston Harbor, anticipated an assault by the state militia and moved his troops from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter. Anderson was a Kentuckian who supported slavery, but his oath to defend the country took priority. President Buchanan sent a merchant ship, the Star of the West, to resupply Anderson and his eighty-two men, but on January 9 secessionists fired on the fort. These shots might have signaled the start of the war, except that the lame-duck president, who opposed secession yet thought the federal government had no right to prevent the states from leaving, had no interest in taking action.

The following week, on January 16, the Senate voted 25 to 23, with all Republicans in the majority, to defeat a compromise measure offered by Senator John J. Crittenden of Kentucky. Crittenden proposed a series of constitutional amendments that would extend the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific, recognize and protect slavery both where it existed and in territories “now held or hereafter acquired,” and forbid Congress to interfere with the interstate slave trade, to abolish slavery in Washington, or to pass any future amendments authorizing itself to interfere with slavery.

Shortly thereafter, representatives from the seven states that had seceded made plans to meet in Montgomery, Alabama. They gathered on February 4 and soon adopted a provisional constitution that would be ratified on March 11. Based on the U.S. Constitution, it provided for one six-year term for president. It recognized the “sovereign and independent character” of each state and asserted that no “law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed.” It also forbade protective tariffs. The convention nominated Jefferson Davis as provisional president of the Confederacy. Davis, a U.S. senator from Mississippi who had also served as secretary of war under Franklin Pierce, resigned his seat once his state seceded, and on February 18 delivered his inaugural speech as president.

Davis stressed that the Confederacy was based on the principles of the Declaration and Constitution of the United States, and that the system of government had not changed, only the interpretation of some of its parts. “We have entered upon the career of independence,” explained Davis, “and it must be inflexibly pursued. Through many years of controversy with our late associates, the Northern States, we have vainly endeavored to secure tranquility, and to obtain respect for the rights to which we were entitled. As a necessity, not a choice, we have resorted to the remedy of separation; and henceforth our energies must he directed to the conduct of our own affairs, and the perpetuity of the Confederacy which we have formed.”

If Davis largely avoided the topic of slavery, his vice president, Alexander Stephens, a friend of Lincoln who had been a Unionist, made explicit the connection between secession and slavery. In a speech delivered in Savannah on March 21, he ridiculed the idea of the equality of the races. “Our new government,” Stephens averred, “is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

On February 11, Lincoln left Springfield for his own inauguration. At various stops along the way to Washington, he spoke only obliquely about “the present national difficulties.” In Philadelphia, on February 22, he declared “there is no need of bloodshed and war” and announced “there will be no blood shed unless it be forced upon the Government.” He was hoping that Southern Unionists would have time to exert their influence; he was hoping that his promise not to interfere with slavery where it existed would be accepted; he was hoping that the secessionists would understand that under no circumstances would he surrender to their attempt to overturn the results of a national election.

March 4, Inauguration Day, began blustery, but by afternoon the weather had turned clear. Lincoln adjusted his glasses, unfolded his speech, and began to read. He again reassured Southerners that he had neither intention nor authority to interfere with slavery where it existed. More significantly, he announced that “the Union of these States is perpetual.” The idea of a perpetual union had only been developed in the years since the nullification crisis, and it held little appeal to those who saw the nation as a compact among states. Lincoln addressed this, too, saying that even if the Union existed as a matter of contract it took all parties to agree to violate it: “no State, upon its own mere motion, can lawfully get out of the Union.” “The central idea of secession,” he declared, “is the essence of anarchy.” Having reaffirmed his constitutional responsibility to defend and preserve the Union, he assured the nation that that there would be no violence or bloodshed “unless it be forced upon the national authority.”

Lincoln went on to restate what he had said many times before: that the only substantial dispute was that “one section of our country believes slavery is right, and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong, and ought not to be extended.” Note the change from his letter to Stephens wherein Lincoln said it ought to be restricted; the new formulation was slightly softer. He built to a conclusion by reminding Southerners that “physically speaking, we cannot separate,” and then he shifted pronouns to “you”: “Suppose you go to war, you cannot fight always; and when, after much loss on both sides, and no gain on either, you cease fighting, the identical old questions, as to terms of intercourse, are again upon you. … In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war.”

He started with policy and he closed with poetry: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break the bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

After Lincoln spoke, Chief Justice Roger Taney administered the oath of office. The president hoped his speech might have done some good, but by the next day he knew that newspapers had responded along sectional lines. Northern papers saw it as conciliatory; Southern papers viewed it as a declaration of war.

Lincoln had little time to wait to see what impact his inaugural address might have. One of the first messages handed to him was news that Major Anderson’s provisions at Fort Sumter would soon be exhausted. While Lincoln and his cabinet debated how to proceed, the Confederate government sent peace commissioners to negotiate with secretary of state William Seward. But as each day passed, Fort Sumter became an increasingly important symbol, and on April 10, Brigadier General Pierre Beauregard, under orders from the Confederate cabinet, demanded the fort’s surrender before it could be resupplied with food.

On April 12 at 4:30 in the morning, the first mortar shell exploded. On April 13, at 2:30 in the afternoon, Anderson surrendered the garrison. No one was killed during the bombardment. Confederate secretary of state Robert Toombs had warned against this action, predicting “it will lose us every friend at the north. You will wantonly strike a hornet’s nest. … It puts us in the wrong. It is fatal.” Northerners rallied to the cause and quickly answered Lincoln’s call for seventy-five thousand troops.

Lincoln’s appeal for state militia troops to deal with the insurrection prompted four additional states to secede: Virginia (April 17), Arkansas (May 6), North Carolina (May 20), and Tennessee (June 8). Before Virginia had decided, Robert E. Lee, a distinguished military veteran and son of a Revolutionary War hero, was offered command of Union forces but declined. On April 20, he resigned from the United States army and instead accepted command of Virginia’s militia forces. Lee said, “I cannot raise my hand against my birthplace, my home, my children.”

By summer, the Confederacy consisted of eleven states, with a total population of nine million, three and a half million of whom were slaves. Four other slave states, border states on the east and west—Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri—remained in the Union, though thousands of men from these states fought for the Confederacy. In many cases, brothers took opposite sides: one of Senator Crittenden’s sons rose to be a general in the Union army; the other became a general in the Confederate army.

The Union consisted of twenty-two states with a population of about twenty-two million people, a half million of whom were slaves. In every way, the North had greater manpower and resources than the South. By war’s end, more than two million men of military age would fight for the North as compared to less than a million for the South. Whereas half the men of military age served for the Union, some three-fourths of all Southern white men served in the Confederate military. The Union had vast superiority in resources such as textile mills and iron works and had a well-developed transportation network, especially railroads. The Union could manufacture almost anything it needed. It also outpaced the Confederacy in food production and had an advantage in numbers of horses and mules.

But wars are not fought on paper, and the Confederacy had distinct advantages of its own. To win, the Union armies would have to invade and conquer; Southerners were defending their homes on familiar territory. The Confederacy was huge (750,000 square miles), with a natural terrain of lengthy rivers and mountainous regions that would make it difficult for any army. The Confederate capital, moved from Montgomery to Richmond in May 1861, may have seemed tantalizingly close, but so was Washington to the Confederate army. In the beginning, the Confederacy also had the tacit support of many leaders of European nations, particularly in Great Britain, which was dependent on Southern cotton. Southerners had a stronger military tradition than Northerners, with seven military academies and a firm belief that one rebel could whip ten Yankees. If the Confederacy needed any reassurance that an inferior force fighting a defensive war on familiar terrain could win, they need only look back to the American revolution. “The Southerners,” commented one observer, “can never be conquered; they may be killed, but conquered never.”

To isolate the Confederacy and prevent it from resupplying, one of Lincoln’s first orders was to impose a naval blockade of all Southern ports. It remained in effect throughout the war and became increasingly effective over time, though it raised a delicate issue of international law. Lincoln never recognized the Confederacy. The states that seceded were involved in a domestic insurrection, and the war was an effort to put down a rebellion. As a result, foreign governments would not be legally justified in recognizing the Confederacy and giving it aid. But a blockade is a tactic used by one sovereign nation against another. By imposing it, Lincoln risked inviting other nations into the conflict, a risk he felt was worth taking in order to begin the process of restoring the nation.

The blockade was a key component in the initial military plan proposed by General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, whose long career dated back to the War of 1812 and who had become a hero during the Mexican War. Scott proposed to cordon off the South and then send a flotilla down the Mississippi to divide and defeat the Confederacy. It was a sound idea, one Jefferson Davis anticipated when he wrote that “to prevent the enemy getting control of the Mississippi and dismembering the Confederacy, we must mainly rely upon maintaining the points already occupied by defensive works; to wit Vicksburg and Port Hudson.” Scott wrote that he hoped “to envelop the insurgent States, and bring them to terms with less bloodshed than by any other plan.”

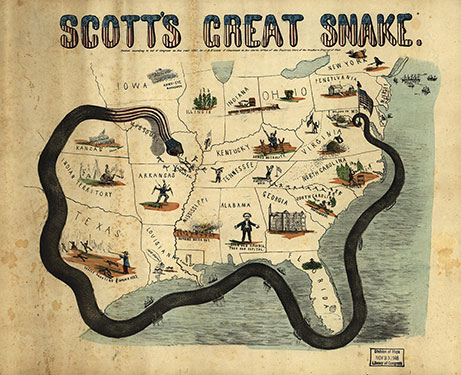

The problem with the plan was that it would take time, and most Northerners were impatient for a quick resolution to the conflict. Opponents derisively labeled Scott’s strategy the “Anaconda plan,” since like the snake it would surround the foe and suffocate it into surrendering. Lincoln also hoped that as the Confederacy became cut off, Southern Unionists, whom he fervently believed constituted a majority of all the Southern states except South Carolina, would rise up and depose the secessionists. In this, he was disappointed.

On July 4, Lincoln met with Congress in special session and outlined his thinking about a war that had already seen skirmishes in Virginia, Missouri, and elsewhere. Lincoln began by offering a history of what had happened at Fort Sumter and deriding the Confederate argument that the assault was “a matter of self defense on the part of the assailants.” The seceding states and they alone, Lincoln thundered, “have forced upon the country, the distinct issue: ‘Immediate dissolution, or blood.’” He expressed his hope to make the contest “a short, and a decisive one,” and asked Congress for money and men. He reminded his audience that there was no such thing as a right to secession, that such an idea was “an ingenious sophism,” and that all Americans who lived by the rule of law must understand that what the nation faced was a domestic insurrection. He expressed his regret at having to employ the war powers of his office, but his only choice was to “perform this duty, or surrender the existence of the government.” The latter, he pledged, he would never do.

4. This cartoon map poked fun at General Winfield Scott’s plan to defeat the Confederacy, primarily by use of a blockade that would cut it off economically. The artist employs the metaphor of a giant anaconda to ridicule the plan.

“It makes my heart sick,” wrote a young man from Tennessee, “to think of the State of our once happy and yet beloved country for there is no history that tells of any country that was ever happyer than ours—and now to see two brave and warlike armies armed with all the deadly instruments that art and wealth could procure marching over our once peaceable country and to think when they meet in the bloody battlefields what destruction … and what misery they can produce.”

As the July heat mounted, believing that a decisive Union victory might accelerate the end of the rebellion, Lincoln ordered an assault against the Confederate army near Manassas, Virginia. Beauregard, who had been given command of Confederate forces after his success at Fort Sumter, had an army of twenty thousand men that threatened Washington, some twenty-five miles away. Union General Irvin McDowell had thirty-five thousand men under his command, and although he was nervous about proceeding with men so lacking in experience, the advance began on July 16. The march proved chaotic, made worse, no doubt, by the unavailability of any reliable maps of Virginia. With the help of good intelligence and by moving units around, the Confederate army was able to prepare itself for the assault.

On Sunday, July 21, McDowell reached his destination and prepared to attack. Curious spectators from Washington, thinking it would make a pleasant day’s entertainment to watch the Union forces fight, arrived in carriages. The initial assault looked promising, but it was repelled when Confederate reinforcements arrived. Late in the afternoon, the rebels launched a counterattack. Their determined rush forward and piercing yell, like the howl of “a thousand dogs,” forced a frantic, disorganized retreat by Union military and civilians alike. It didn’t help that uniforms this early in the war had not been standardized and Northern troops mistook Confederates in blue for Union men. In the end, on both sides, hundreds were killed and well over a thousand were wounded. Far worse was yet to come.

Reading reports of the battle in London, Henry Adams, serving as secretary to his father, Charles Francis Adams, minister to England, wrote that “Bull’s Run will be a by-word of ridicule for all time … the disgrace is frightful. … If this happens again, farewell to our country for many a day.” Lincoln reacted by demoting McDowell and bringing in George McClellan to command the forces now named the Army of the Potomac. McClellan was young and ambitious. He was also a Democrat who came to believe “I have become the power of the land” and privately labeled Lincoln “the original gorilla.” Whatever his megalomaniacal tendencies, he knew how to train and organize an army that grew to over one hundred thousand men, and he spent much of the rest of the year in preparation. In November, Winfield Scott retired, and Lincoln promoted McClellan to commander of all Union forces.

Lincoln soon faced a delicate political and military issue when, on August 30, General John C. Fremont, commander of the western department of the Union effort, issued a proclamation that placed Missouri under martial law and declared free the slaves in that state who belonged to supporters of the rebellion. Fremont, who had been the first Republican nominee for president in 1856, was called a hero by those aching to see the war quickly transformed into a war against slavery. One writer anointed him “the people’s first leader against the great slaveholders’ conspiracy.”

Lincoln was upset. He told the general that the clause freeing the slaves was “objectionable.” It violated the terms of the Crittenden-Johnson resolution, passed by Congress on July 25, which reaffirmed the position that the war was not being fought to overthrow or interfere with established institutions. It also did not conform to the terms of a Confiscation Act, signed on August 6, which provided for the confiscation of slaves only if they were being used directly in support of the insurrection. Reaction to Fremont’s proclamation threatened the delicate balance with those border states still in the Union. Indeed, if it stood, Kentucky seemed very likely to secede from the Union. The proclamation itself violated Lincoln’s assurance that he had no intentions of interfering with slavery where it existed. After Fremont refused to modify the order, Lincoln revoked it and eventually removed Fremont from command.

But the issue of the slaves as a matter of military policy was not driven only by the wishes of commanders. As early as May, General Benjamin Butler reported that several slaves had escaped Confederate lines and arrived at Fort Monroe, Virginia. He dubbed them “contraband of war,” and for the rest of the war runaway slaves who presented themselves to Union lines were known as contrabands. By July, there were nearly a thousand of them in Butler’s camp. These contrabands seemed to fit uneasily, however, under the terms of the Confiscation Act. Northern Democrats were displeased, as were conservative Republicans, but abolitionists hoped events would transform Union war aims into a struggle against slavery. Charles Loring Brace, a leading reformer and founder of the Children’s Aid Society, wrote that when “a National Declaration of Emancipation to the slave … has been widely scattered and proclaimed, and the slaves understand it—as they would marvelously soon—we have a nation of allies in the enemy’s ranks. There is a foe in every Southerner’s household.” Frederick Douglass, an electrifying orator and writer whose published account of his travails as a slave had opened Northern eyes in 1845, proclaimed in May that the “‘inexorable logic of events’” would force upon the administration and American people an awareness that “the war now being waged in this land is a war for and against slavery.” In time, runaway slaves would help make it so.

From the start of the war, slavery also played a critical role in diplomatic relations. The Confederacy was eager to win European recognition and support. Most European governments were antislavery and this played a role in keeping them from rushing to the Confederacy’s aid, though they certainly desired the cotton imports. Furthermore, foreign governments didn’t want to side with a losing cause, so they waited to see how the military conflict would proceed. Diplomacy on both sides was vigorous, especially in regard to Great Britain, which was deeply affected by the American conflict and whose aristocracy tended to be sympathetic toward the South, whereas its working classes supported the North. When on May 14 the British government recognized the belligerent status of the Confederacy, which allowed the South to borrow money and purchase nonmilitary supplies, the Union feared this was a first step toward official diplomatic recognition.

An event toward the end of the year nearly brought Great Britain into the war on the Confederate side. On November 8, Captain Charles Wilkes of the United States warship San Jacinto boarded a British vessel, the Trent, and removed two Confederate commissioners, James Mason of Virginia and John Slidell of Louisiana, headed to Europe on a diplomatic mission. The Confederate commissioners, who had instructions to argue that the blockade was illegal whereas secession was legal, and that Great Britain would benefit from a Confederate victory, were brought to a prison in Boston.

The British government reacted with indignation. Lord Palmerston, the prime minister, considered it “a deliberate and premeditated insult” intended to provoke England. One writer informed Seward, “the people are frantic with rage, and were the country polled I fear 999 men out of one thousand would declare for immediate war.” Lincoln’s administration responded by saying that Wilkes had acted without authorization. The two prisoners were released on New Year’s Day and made their way to Europe. For the time being, the war remained an internal affair between the United States and the Confederate States.

Addressing the Confederate Congress on November 18, Jefferson Davis spoke positively about the course of the war for the Confederacy: “A succession of glorious victories at Bethel, Bull Run, Manassas, Springfield, Lexington, Leesburg, and Belmont, has checked the wicked invasion which greed of gain and the unhallowed lust of power brought upon our soil, and has proved that numbers cease to avail when directed against a people fighting for the sacred right of self-government and the privileges of freemen.” Of course, Davis conveniently neglected some important Union victories in western Virginia and along the South’s Atlantic coast, but this speech was meant to be inspirational. He concluded with a discussion of the Trent affair, restating his belief that the blockade was a farce and requesting “a recognized place in the great family of nations.”

Lincoln sent his annual message to Congress on December 3. He addressed the question of foreign involvement and observed that “a nation which endures factious domestic division, is exposed to disrespect abroad; and one party, if not both, is sure, sooner or later, to invoke foreign intervention.” As for the commercial reasons that might induce European involvement, Lincoln reminded Congress that it was the intact Union that made for valuable commerce, and not “the same nation broken into hostile fragments.” He reaffirmed his decision not to hastily employ “radical and extreme measures” that would affect loyal citizens as well as disloyal ones, and expressed his anxiety that the conflict with the seceded states “not degenerate into a violent and remorseless revolutionary struggle.” In 1862, he would change his mind about the first and see the second come to pass.