Chapter 4

1863

On January 1, Thomas Wentworth Higginson attended services to commemorate the Emancipation Proclamation. Higginson had been one of the secret six that supported John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, and was now serving at Port Royal, South Carolina, as the colonel of the First South Carolina Volunteers, the first black regiment authorized by the federal government during the war. Located in Beaufort County, Port Royal fell into Union hands early in the war and, since then, Northern whites and local blacks had participated in an experiment in free plantation labor.

The proclamation was read and the colors presented. As Higginson saluted the flag,

there suddenly arose, close beside the platform, a strong male voice, (but rather cracked and elderly), into which two women’s voices instantly blended, singing, as if by an impulse that could be no more repressed than the morning note of the song-sparrow,

My Country ’tis of thee,

Sweet land of liberty,

Of thee I sing … !

I never saw anything so electric; it made all other words cheap; it seemed the choked voice of a race at last unloosed.

Lincoln had followed through and issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The final Proclamation included several important changes from the preliminary decree announced one hundred days earlier. It omitted any reference to schemes of colonization. It specified those places that were “this day in rebellion against the United States” and declared that all persons held there as slaves “henceforward shall be free.” (The preliminary decree said “forever free,” but now that the deed was done, as opposed to promised, the additional rhetoric seemed unnecessary.) The document also included a provision for receiving “persons of suitable condition” into the military. This would prove to be of signal importance in the war effort and for the future of African Americans. At a meeting with his cabinet held December 31, Lincoln added a line, proposed by Salmon Chase, that allowed the legalistic document to breathe: “And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of almighty God.”

The Proclamation elated Northern Republicans, dismayed Northern Democrats, and outraged Southern rebels—Jefferson Davis called it the “most execrable measure recorded in the history of guilty man.” The enslaved heard the news that the day of Jubilee had come, and their pace of escape to Union lines increased: “whole families of them are stampeding and leaving their masters,” wrote one officer. Many Union soldiers responded with joy that the war was not merely a battle “between North & South; but a contest between human rights and human liberty on the one side and eternal bondage on the other.” But others expressed alarm. A surgeon with the Army of the Potomac confessed, “I have no fancy for emancipating a lot of uneducated wild, ferocious, and brutal negroes.” Some officers complained to the president about this dramatic shift in military objectives and asked him to revoke the Proclamation. Lincoln responded that “broken eggs can not be mended. I have issued the emancipation proclamation and I cannot retract it. … And being made, it must stand.”

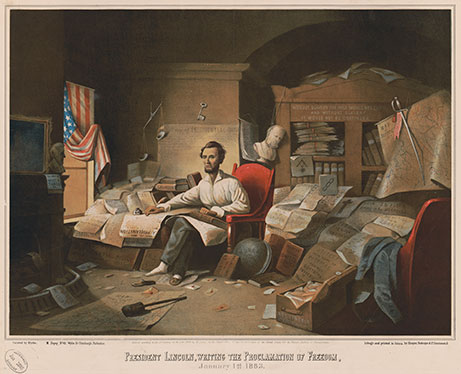

6. This print captures the strain on Lincoln as he drafted the Emancipation Proclamation. Looking haggard and sitting in shirtsleeves and slippers, he has his hand on a Bible that rests atop the Constitution. The print is crammed with symbols and references, including allusion to John C. Calhoun, Andrew Jackson, James Buchanan, and George Washington.

The Proclamation was one of several actions Lincoln took in January in his effort to advance the Union’s military success. On January 4, he ordered General Grant to rescind his Special Order Number 11, which had expelled all Jews as a class from his military department. Henry Halleck, who like Grant evinced hostility to Jewish merchants, said the president opposed proscribing “an entire religious class, some of whom are fighting in our ranks.” Later in the month, Lincoln replaced Burnside with Joseph Hooker as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker had graduated from West Point in 1827 and served in the Mexican War. He was ambitious, and after making the appointment Lincoln warned him to “beware of rashness.” After the defeat at Marye’s Heights, the army needed reorganization and a morale boost, and Hooker provided it. Finally, in the west, Grant personally took over the campaign against Vicksburg, Mississippi, which had begun unsuccessfully in December 1862.

The war was taking its toll north and south. Military losses and a shortage of enlistments led Lincoln to sign an Enrollment or Conscription Act on March 3. Male citizens between the ages of twenty and forty-five had to enroll, and quotas for various congressional districts were set to be filled by the states. As with Confederate conscription, the Union draft permitted the hiring of substitutes. On both sides there were also serial volunteers, men who would enlist, receive as much as several hundred dollars in gold, and desert, only to sign up again for another bounty. By midsummer, the draft would lead to violent conflict.

The Confederacy had instituted its draft a year earlier but now found itself suffering from shortages of food and goods. Attempts to convince planters to switch from cotton to food production had limited success. And Southerners bristled at being told by the government not to distill liquor from corn because the grain was needed. Drought in 1862 had destroyed much of the crop in Virginia and elsewhere, and a scarcity of salt, which was used as a preservative, kept army meat rations skimpy. High inflation crippled the economy as the price of wheat and milk tripled. Speculators tried to profit off of the situation, and in several cities riots took place in the spring. On April 3, in Richmond, women broke into food and clothing stores, shouting “bread, bread.” Only the threat of the militia firing broke up the crowd.

Seeking a solution to the food problem, the Confederate Congress passed a tax-in-kind law on April 24. The tax took 10 percent of all agricultural produce and any livestock raised for slaughter. It did little to ease the supply crisis, but it increased tensions within the Confederacy over how the war was being fought and whether its professed principles were being upheld. States’ rights ideologues, who believed that the reason for secession was to escape a tyrannical centralized government, were increasingly reluctant to comply with the Confederate government’s demands, essential though they were to waging war effectively.

The Chancellorsville Campaign of April 30 to May 6 renewed Confederate hopes. After crossing the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers above Fredericksburg, Hooker’s army of 115,000 concentrated near Chancellorsville. Faced with superior numbers attacking his force of sixty thousand, Lee boldly divided his army. Meeting resistance on the Orange Turnpike, which led to Fredericksburg, Hooker inexplicably halted, assumed defensive positions, and yielded the initiative to Lee, who again divided his forces, sending Stonewall Jackson to attack the Union right flank. They were unprepared for the attack. Hooker never brought his reserve forces into the battle, and after several days the Army of the Potomac retreated. The Union suffered 17,000 casualties compared to 12,800 for the Confederacy. But one of those Confederate casualties was Stonewall Jackson, a man described by Lee as “my right arm,” who died eight days later from complications with a wound received in battle. Lee had won a brilliant victory but had failed to follow up. He hardly could, with troops ragged and undernourished, men and horses severely undersupplied. Instead, he would reorganize his army and prepare to invade the North.

When news of the loss reached Washington, Lincoln could not contain his despair. “What will the country say! What will the country say!” he cried. At the same time, he faced a political crisis in the Union over what he called “the fire in the rear,” the vocal opposition of Northern Peace Democrats to the ongoing prosecution of the war. Dismayed by declarations of sympathy for the enemy, General Burnside, commanding the military district of Ohio, issued an order in April that anyone who acted in support of the enemy would be tried as a spy or traitor and executed if convicted.

It didn’t take long before Clement Vallandigham tested the order. A former Democratic congressman, Vallandigham had his eye on the governorship of Ohio. When he delivered a speech on May 1 denouncing Lincoln and the war effort, it was not the first time that he had spoken out. On January 14 in an address to the House, “The Great Civil War in America,” he had declared that the war should not continue, its cause was not slavery but abolition, and peaceful reunion was still possible. But now, before a crowd of ten thousand in Mt. Vernon, Ohio, he lambasted a “wicked, cruel, and unnecessary war, one not waged for the preservation of the Union, but for the purpose of crushing out liberty and to erect a despotism; a war for the freedom of the blacks and the enslavement of the whites.”

Vallandigham was arrested for violating Burnside’s order. Authorities denied him a writ of habeas corpus and tried him before a military tribunal, which found him guilty and sentenced him to two years’ confinement. Lincoln altered the sentence to banishment but upheld his general’s orders. A political firestorm erupted. The president, who had only selectively addressed the public directly on state matters, decided to issue a letter in response to a protest from a group of New York Democrats led by Erastus Corning, head of the New York Central Railroad, who condemned the arrest and trial as “a fatal blow” to the liberties guaranteed by the Constitution.

In the missive, Lincoln did not simply declare his position; he walked readers through his logic. “Ours is a case of rebellion,” he said, “in fact, a clear, flagrant, and gigantic case of rebellion.” The Constitution stated that the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended except in “cases of rebellion or invasion.” Lincoln said that in this case there was no distinction between areas of military occupation and those not so occupied—the whole nation was at war, and Vallandigham’s arrest “was made because he was laboring, with some effect, to prevent the raising of troops; to encourage desertions from the army; and to leave the rebellion without an adequate military force to suppress it.” He then asked readers: “Must I shoot a simple-minded soldier boy who deserts, while I must not touch the hair of the wily agitator who induces him to desert?” and answered his own question: “I think that in such a case to silence the agitator, and save the boy is not only constitutional, but withal a great mercy.” He must have known as well how soldiers felt. One captain wrote to his brother, “My first object is to crush this infernal Rebellion the next to come North and bayonet such fool miscreants as Vallandigham.”

As Lincoln sought to quell the fire in the rear, the fire on the front gathered force. Through the spring, Grant planned and executed an assault on Vicksburg, which sat on a bluff high above the Mississippi on its eastern bank. To take the heavily fortified fortress at Vicksburg would be to control the mighty river, gain access to the lower Confederacy, and cut off the trans-Mississippi Confederacy from the rest of it. Overcoming great obstacles, Grant marched his army south of Vicksburg and sent supporting barges and transports down the river past the Confederate batteries, which fired relentlessly on the flotilla. He then recrossed the river. Living off of the land, Grant’s army, now divided, fought its way west and defeated opposing forces at Jackson (May 14), Champion Hill (May 16), and Big Black River (May 17). Grant now had Confederate general John Pemberton’s army trapped at Vicksburg. After two brutal frontal assaults failed, Grant settled in for a siege of the city. His men dug miles of trenches and tunnels, some of which reached into Confederate lines. The siege would be a long one, and at times, at night, soldiers from each side gathered to exchange rations and stories. Lincoln called the campaign—whether or not Vicksburg fell—“one of the most brilliant in the world.”

As Vicksburg came under siege, another general who had Proved to be a brilliant tactician planned a Confederate invasion of the North. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had eighty thousand men organized into three infantry corps led by James Longstreet, Richard Ewell, and Ambrose Powell Hill. James E. B. Stuart, who had literally run a circle around McClellan’s Army of the Potomac a year earlier in the Peninsula campaign, commanded the cavalry. In May, the Confederate cabinet gave approval to Lee’s plan, which had several objectives: to relieve pressure on Richmond, to exploit the rich resources of the Pennsylvania countryside, and perhaps, by capturing a major Northern city, to win support for the Confederacy from England. Harper’s Weekly speculated that Lee’s invasion sought to boost Confederate morale in the face of the siege at Vicksburg but thought it could not possibly succeed because “no army the size of Lee’s can operate as a moving or flying column without a base.”

Lincoln feared that Hooker was not up to the task of confronting Lee. He was frustrated that, like McClellan, the general seemed more focused on Richmond than on Lee’s army. He told Gideon Welles that “Hooker may commit the same fault as McClellan and lose his chance.” “Almost every one sees,” wrote one newspaper correspondent, “that if General Lee gains a decisive victory over Hooker, which he is very likely to do, the cause of the North is virtually lost.” On June 28, Hooker offered his resignation; Lincoln appointed George Gordon Meade to command the Army of the Potomac.

Like his predecessor, Meade had graduated from West Point in 1835 and served in the Mexican War. He had also worked as a civil engineer. He had been wounded during the Seven Days’ battles but had recovered and had fought at Second Bull Run. Coming so suddenly, the appointment shocked Meade, and he protested against it. He took command just days before the battle against Lee commenced on July 1 when a Confederate brigade encountered Union cavalry along the Chambersburg Pike west of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. After the first day of fighting, Confederates drove back outnumbered Union forces, who took a position on Cemetery Hill. That evening, the remaining forces on both sides reached Gettysburg—a total of more than 150,000 men (83,000 Union and 75,000 Confederate).

On July 2, Lee ordered Longstreet to attack the Union left, with a secondary assault on the right led by Ewell. The day saw gruesome combat as Confederates repeatedly attacked and Union forces held their ground. The fighting on the left occurred at Little Round Top, Devil’s Den, the Wheat Field, and Peach Orchard and the fighting on the right at Culp’s Hill. A few weeks later, a Union soldier wrote:

Bullets whistled past us; shells screeched over us; canister and grape fell about us; comrade after comrade dropped from the ranks; but on the line went. No one took a second look at his fallen companion. We had no time to weep … forward we went again and the Rebs were routed, and the bloody field was in our possession; but at what a cost! The ground was strewed with dead and dying, whose groans and prayers and cries for help and water rent the air. The sun had gone down and in the darkness we hurried, stumbled over the field in search of our fallen companions, and when the living were cared for, laid ourselves down on the ground to gain a little rest, for the morrow bid far more stern and bloody work, the living sleeping side by side with the dead.

On July 3, Lee decided to attack the Union center, embedded along Cemetery Hill. Longstreet thought it would be better to outflank the Union line on the left and maneuver behind them. But Lee was determined to fight. A division of fresh troops led by George Pickett had arrived the night before. In the morning, Union soldiers battled at Culp’s Hill and regained what they had lost the day before. At the same time, J. E. B. Stuart’s cavalry, which had arrived only the previous day, failed in an attempt to sneak behind Union lines. At one o’clock in the afternoon, Confederate artillery began an intense bombardment of the Union center. For a time, Union artillery responded, but then it stopped, for several reasons: to conserve ammunition, to deceive the Confederates into thinking they had put it out of action, and, as one Union artillerist honestly put it, to endure “dreadful artillery fire [that] seemed to paralyze our whole line for [a] while.” After two hours of shelling, the rebels emerged from the woods.

Nine infantry brigades, some 12,500 men, led an assault across three-fourths of a mile of undulating open field toward entrenched Union positions behind a low stone wall. The Confederate line stretched a mile wide, with Pettigrew and Trimble on the left and Pickett on the right. The assault, straight into a “torrent of iron & leaden ball,” lasted an hour. When it ended, the Confederate attackers were decimated, having suffered casualties of 50 percent. Thousands were killed, wounded, or captured, with extremely high casualties among officers. A few brave Confederates made it over the stone wall and there ended their journey. Pickett would never get over the destruction of his division, and after the war those generals who hailed from Virginia would cast blame on Longstreet, who was born in South Carolina and had expressed concern about Lee’s plan. As Lee sought to gather what was left of his army (he suffered total casualties of over twenty-eight thousand; the Union lost nearly twenty-three thousand) he was heard to say, “It’s all my fault.” Later, he would blame Longstreet and Stuart. He would also offer a jeremiad, pronouncing “we have sinned against almighty God” and calling for a purging of collective sin to win God back to the Confederate side.

It poured on the evening of July 4. The next day, Union troops renewed their march. One soldier wrote:

Crossing the battlefield—Cemitary Hill—the Great Wheat Field Farm—Seminary ridge—and other places where dead men, horses, smashed artillery, were strewn in utter confusion, the Blue and the Grey Mixed—Their bodies so bloated—distorted—discolored on account of decomposition having set in that they were utterly unrecognizable, save by clothing, or things in their pockets—The scene simply beggars description.

7. One of the most iconic photographs of the Civil War, this image shows bloated bodies lying in the foreground as fog-shrouded figures loom in the background. The corpses are shoeless, their footwear removed to supply others.

Lee retreated from Gettysburg, but Meade did not counterattack, and his failure to do so enraged Lincoln, especially after rains came and the rising waters of the Potomac prevented Lee from crossing back into Virginia. On July 14, he wrote a letter to Meade: “My dear general, I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape. He was within your easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with our other late successes, have ended the war. As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely.” Lincoln decided not to send the rebuke, using back channels instead to get his message to the general.

One of the other successes Lincoln alluded to was Vicksburg, which, on July 4, surrendered to Grant. Pemberton’s force of thirty thousand had been reduced by disease as well as the constant shelling inflicted on the city. The diary of one Mississippi soldier narrated the struggle to survive on quarter rations, weeds, slaughtered mules, and trapped rats. The soldiers sent the commander a petition on June 28: “If you can’t feed us, you had better surrender.” The siege had lasted forty-six days. Pemberton delivered his men and arms. Grant paroled the soldiers, allowing them to go home after they swore not to take up arms again. He used the captured rifles to reequip his men.

On both sides, commentators recognized the momentousness of the event. Jefferson Davis had said that “Vicksburg is the nail head that [holds] the South’s two halves together.” If so, the nail had been pulverized. One Confederate wrote, “This is the most terrible blow that has been struck yet.” Davis, “in the depth of gloom,” confessed “we are now in the darkest hour of our political existence.”

Gideon Welles noted in his diary that “the rejoicing in regard to Vicksburg is immense … [it] has excited a degree of enthusiasm not excelled during the war.” Lincoln wrote to Grant, whom he had never met, and thanked him for “the almost inestimable service you have done the country.” Sherman wired Grant calling it “the best fourth of July since 1776. Of course we must not rest idle, only don’t let us brag too soon.”

Sherman was prescient. More good news arrived with word of the surrender of Port Hudson on July 9, which gave complete control of the Mississippi to the Union. But then New York exploded in riots over the draft. On July 11, names were first drawn in New York in compliance with the Conscription Act passed several months earlier. Two days later, another drawing was to be held, but a crowd of several hundred attacked the draft office. Many of the protesters were Irish immigrants, Democrats who had multiple resentments: that the wealthy could buy substitutes for $300, that the war showed no sign of ending, and that they had to compete for jobs with free blacks, whose numbers they believed would only grow with emancipation. The rioters overwhelmed the police and let loose on the black community a wave of horrific racial violence. They burned buildings, including the Colored Orphan Asylum, and lynched more than a dozen blacks, stringing them up from lamp posts. They also sought out the homes of leading Republicans such as Horace Greeley. After two more days of violence, the riots subsided when New York militia regiments arrived to reestablish order. One witness testified afterward: “I believe if I were to live a hundred years I would never forget that scene, or cease to hear the horrid voices of that demoniacal mob resounding in my ears.”

Lincoln would not tolerate rebellion against federal authority in the North any more than he tolerated it in the South. He reasserted his intentions to “see the draft law faithfully executed.” When New York next held draft selection, twenty thousand troops made certain there was no violence. Ironically, at the moment that racial hatred ignited draft riots, black troops began to make their presence felt in the war effort.

Prior to 1863, selected black units had been organized. Lincoln feared that arming blacks, including those formerly enslaved, would result in the loss of the border states, and he shared many of the prejudices of the day concerning the ability of black men in the field, believing that they would either be too docile or too savage. But all of this changed with the Emancipation Proclamation, which called for accepting blacks into the military. Lincoln came to realize that “the colored population is the great available and yet unavailed of, force for the restoration of the Union. … The bare sight of fifty thousand armed, and drilled black soldiers on the banks of the Mississippi, would end the rebellion at once.”

Lincoln thought of black soldiers primarily as helping to end the war, but recruiters such as Frederick Douglass saw more deeply into the meaning of their service. Only by allowing black men to fight would “the paper proclamation … be made iron, lead and fire.” And their service would not only help save the union but also win them citizenship rights: “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”

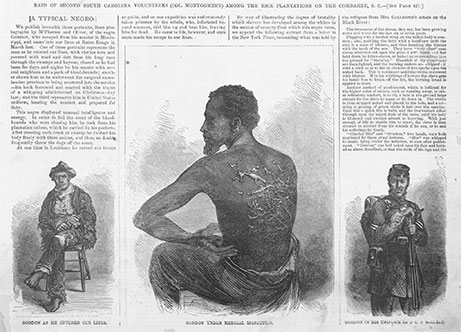

Images as well as words played a role in the recruitment process. When during the spring a runaway slave appeared in Union lines, a photographer had him pose with his shirt off. The resulting image shocked viewers who saw evidence of the barbaric cruelty of slavery; yet the beaten slave still held his chin up and even defiantly placed his hand on hip. Entitled “The Scourged Back,” or “A Map of Slavery,” that photograph circulated as a carte de visite. One newspaper declared that the “Card Photograph should be multiplied by the 100,000 and scattered over the states. It tells the story in a way that even Mrs. Stowe cannot approach because it tells the story to the eye.”

The image also appeared as an engraving in Harper’s Weekly in its issue of July 4, 1863. Under the title “A Typical Negro,” the weekly told the man’s story. His name was Gordon, and he had entered Union lines at Baton Rouge, having escaped from his master in Mississippi. During his escape, he carried onions to throw dogs off his scent. He arrived tattered and starving, as depicted in the first sketch. The second, drawn from the photograph, shows him undergoing examination before being mustered into the service. And the third “represents him in United States uniform, bearing the musket, and prepared for duty.” The images served as an effective recruitment poster.

By war’s end, nearly 180,000 men served in the United States Colored Troops, close to 10 percent of the entire Union army. Another nineteen thousand served in the navy. Black soldiers faced myriad difficulties. Though eager to see combat, most of them were initially placed in noncombat situations working on fortifications or as teamsters and cooks. And they suffered the taunts of white soldiers, who enjoyed such pranks as sneaking up on blacks and throwing flour in their faces. Prejudice against them meant not only skepticism about their ability to fight but also harsher punishments and unequal treatment. They served in segregated units commanded by white officers and received less pay than white soldiers—$10 per month with $3 deducted for clothing, compared to $13 plus a clothing allowance for white soldiers; one outraged black corporal wrote directly to the president and declared, “We have done a Soldier’s duty. Why can’t we have a Soldier’s pay?” Finally, captured black soldiers faced a Confederate threat of being returned to slavery, a threat that led Lincoln to issue a general order that announced there would be reprisal against any Confederate prisoners should black troops or their white officers face mistreatment.

8. This engraving of Gordon was based on a photograph of the runaway slave who entered Union lines and showed his back, scarred from the many whippings he had received. He would leave camp a soldier, one of tens of thousands of black men who served in the Union army.

In combat, when the chance came, black troops proved their valor and won over skeptics. They played an important role at Port Hudson and Milliken’s Bend in the Vicksburg Campaign (one soldier wrote, “The problem of whether the Negroes will fight or not has been solved”). Their performance on July 18 at Fort Wagner, south of Charleston Harbor, where the Massachusetts Fifty-fourth under Colonel Robert Gould Shaw led the assault, forever earned them respect. Shaw was killed, as were scores of his men. He was buried with them in a pit. One bitter Massachusetts officer, blaming Shaw’s death on his troops, groused, “niggers won’t fight as they ought.” But a soldier from Ohio expressed a more widespread and growing belief: “There is not a Negro in the army that is not a better man than a rebel, and for whom I have not a thousand times more respect than I have for a traitor.” Arming blacks, General Grant declared, was “the heaviest blow yet given the Confederacy.”

Lincoln grew tired of hearing from supporters of the Union still upset by the Emancipation Proclamation and other administration policies. In August, he used an invitation from his friend James Conkling to write a letter to be delivered at a Union rally in Illinois, held on September 3. Conkling had the missive read to the crowd of fifty thousand there, and it was later published in newspapers throughout the Union.

Lincoln defended the Proclamation, saying that “as law, [it] either is valid, or is not valid. If it is not valid, it needs no retraction. If it is valid, it can not be retracted any more than the dead can be brought to life.” He went further: “Some say you will not fight to free negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you; but, no matter. Fight you, then, exclusively to save the Union.” He expressed hope, in the aftermath of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, that peace might come soon. When that day arrived, he said, “there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they have strove to hinder it.”

The speech electrified readers, united supporters, and perhaps even converted a few critics. The New York Times named Lincoln a “leader who is peculiarly adapted to the needs of the time.” The Chicago Tribune called it “one of those remarkably clear and forcible documents that come only from Mr. Lincoln’s pen. … God bless Old Abe.”

And yet the war showed no signs of relenting. A border war between Kansas and Missouri turned savage on August 21, when William Quantrill, leader of a pro-Confederate guerilla band, raided Lawrence, Kansas, and murdered some two hundred men and boys and burned down buildings. “The citizens were massacred by the light of their burning homes, and their bodies flung into wells and cisterns,” reported one paper. “No other instance of such wanton brutality has occurred during the American war.”

In September, a year after Antietam, Union forces under William Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland engaged in a brutal battle with Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee at Chickamauga, Georgia. Earlier in the year, in June, Rosecrans had managed dramatic success against Bragg when he took Chattanooga, but his accomplishment went almost unacknowledged in the Union successes at Vicksburg and Gettysburg. Now, Bragg had Longstreet, who arrived from Virginia in time to break through Union lines and drive them back to Chattanooga. Combined casualties were nearly 35,000 out of some 120,000 engaged. The victory provided the Confederacy with a morale boost. “The whole South will be filled again with patriotic fervor,” noted a Richmond resident. Writing to his brother, Henry Adams predicted that the loss “ensures us another year of war.”

Two months later, fortunes would be reversed at Missionary Ridge, which stretched southeast from Chattanooga. In October, Lincoln had placed Grant in charge of the entire western military department. Grant traveled to Chattanooga to oversee operations in the Tennessee theater. Bragg was dug in atop the seemingly impregnable four-hundred-foot ridge. And yet on November 25, Union forces charged up the ridge and drove the rebels from their position, routing Bragg and his army. The next day, a civilian clerk wrote, “It would seem incredible to one who had not seen it, to think that men could climb up such a hill, in face of the fire they were receiving, and not only get up the hill, but, actually drive a force, superior in numbers off of it.” The Union now held Chattanooga, the “Gateway to the Lower South.” For the most part, the remainder of the year was quiet as both armies settled into winter quarters, waiting for the spring to resume warfare.

On November 19, days before the success at Missionary Ridge, Lincoln visited the site of the summer’s momentous Union victory at Gettysburg to participate in ceremonies dedicating the Soldiers National Cemetery. The main speaker was Edward Everett, former governor and senator from Massachusetts, whose oration went on for two hours. Following a hymn, Lincoln offered his remarks, approximately 272 words, though the total varies with a word here, a word there, in the five known manuscript copies of the address.

The speech’s rhetoric was historical and biblical, as Lincoln grounded the meaning of the war in what took place in 1776 (four score and seven years earlier) and defined what had taken place then as the creation of a nation devoted to liberty and equality. The cadences are musical, the rule of threes doing its work effectively: “we cannot consecrate, we cannot dedicate, we cannot hallow this ground”; “of the people, by the people, for the people.” Lincoln separated words from actions, knowing that in war the latter were the coin of victory, and yet words helped give meaning to deeds.

Lincoln’s opponents were livid. They saw what he had done. He had hijacked the meaning of the nation in such a way as to make liberty and equality central to its identity, and he had taken the events of the year—from emancipation through Gettysburg and Vicksburg and through the enlistment of black troops—to define what this “great civil war” was about: not simply restoring the Union but creating a better nation dedicated to making palpable the principles of the revolution. A Democratic newspaper called it “a perversion of history so flagrant that the most extended charity cannot regard it as otherwise than willful.”

Lincoln was already contemplating the end of the war and how the nation would be reconstituted. It was a question he was not alone in considering. More than a year earlier, one soldier wondered in his diary: “What shall we do with the conquered country? With the slaves? With meddlesome foreigners? With our vast debt? With the rebels themselves?” On December 8, the president issued a “Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction.” Lincoln offered a full pardon to participants in the rebellion (except government officials, high-ranking officers, and those rebels who had mistreated prisoners of war) who took an oath of allegiance, with property restored to them save for slaves. Furthermore, whenever 10 percent of those who voted in a state in the election of 1860 took the oath, state government could be reestablished and would be recognized. He also declared he would not object to provisions established to aid former slaves, “a laboring, landless, and homeless class” of people.

The proclamation initially pleased both radical and conservative elements within the Republican Party. It was a first attempt to look beyond the war to the terms of reconstruction—the ways the divided nation would be restored to one. The proclamation also seemed to play to a growing peace movement within the Confederacy, as representatives hostile to Jefferson Davis gained seats in the fall elections and North Carolina expressed interest in opening separate peace negotiations. But the process of reconstruction was still a long way off. Late in the year, both sides began to strategize over the presidential election scheduled for 1864. In a war that had not been going well for the Confederacy, the defeat of Lincoln might still salvage the rebels’ cause. Entering the year, Lincoln was uncertain about his chances. There was not only much war weariness and opposition from Northern Democrats but also dissent from radical and conservative Republicans. The nation was not yet ready for reconstruction, not by a long shot.