Chapter 5

1864

In December 1863, Salmon Chase suggested adding the phrase “In God We Trust” to American coins, and with the Coinage Act of 1864 Congress approved the motto. Both sides believed that God supported their cause, and soldiers often expressed a deep religious faith, at least in combat. “If ever one needed God’s help,” wrote a Georgia private, “it is in time of battle.” Though the embrace of religion seldom showed in attendance at Sunday services in camp, one soldier observed that “still there is large amt of a certain kind of rude religious feeling.” Through 1864, Confederate soldiers in particular experienced revivals of religion. They held prayer meetings and used faith to spur courage. But at the start of the year, problems within the Confederacy were taking their toll. One North Carolinian wrote to the governor, “The tide is against us, everything is against us. I fear the God who rules the destinies of nations is against us.”

With the effects of the blockade taking hold, and ill-advised fiscal policies that relied heavily on paper money to finance the war, inflation began to wreak havoc. Planters had failed to shift from cotton to staples, and transportation networks, such as they were, had been disrupted. One diarist listed prices in Richmond as $275 a barrel for flour; $25 a bushel for potatoes; $9 a pound for bacon. A pair of shoes could cost over $100. In 1860, a typical Southerner spent $6.55 to feed a family for a week; by 1864 the amount had ballooned to $68.25 for the same staples. Women especially, held up in Southern culture as refined and pure, carried the burden and suffered from want and fear, especially in situations where they were left alone to manage slaves. Perhaps as many as one in ten Confederate soldiers deserted, many to return to help their families. A revised Conscription Act passed in February made men aged seventeen to fifty susceptible to the draft. “We want this war stopped,” wrote one man. “We will take peace on any terms that are honorable.”

Jefferson Davis faced not only an unraveling economic situation, but a difficult political one as well. More extreme political elements in the government, such as Barnwell Rhett and William Yancey, had little respect for the Confederate president. Davis had cobbled together his cabinet to appease the interests of individual states rather than bring the best people into government. Rather than lubricating the engine of government, one-party politics actually made it more difficult for Davis to act as a strong executive because a constantly changing constellation of interests pulled and pushed in different directions; by comparison, in the Union, the existence of the Democrats helped unify the Republicans in support behind Lincoln. Davis enjoyed no such support. Indeed, many an antiadministration official came to feel about Davis as did the editor of the Southern Literary Messenger, who called him “cold, haughty, peevish, narrow-minded, pig-headed, malignant.” And the tension between the doctrine of states’ rights and the need for national actions continued to impede the Confederate war effort as governors resisted Davis’s call for men and material.

Despite being ridiculed as “no military genius,” Davis inserted himself directly into military affairs and throughout the spring consulted with Lee about operations. They were especially concerned about what Grant might do. On March 1, Lincoln nominated Grant to command all armies, and on March 9, a day after meeting him for the first time, Lincoln placed him in charge. Grant made his headquarters the Army of the Potomac, located where Union forces would be going head-to-head against Lee. But where they would tangle remained uncertain. On March 25, Lee wrote to Davis and warned him of falling prey to reports in Northern newspapers as to Union military intentions. “I would advise,” Lee wrote, “that we make the best preparations in our power to meet an advance in any quarter, but be careful not to suffer ourselves to be misled by feigned movements into strengthening one point at the expense of others, equally exposed and equally important.”

Grant’s strategy was for Meade’s Army of the Potomac (one hundred fifteen thousand men) to move against Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia (sixty-five thousand men). Auxiliary attacks would include action on the James River and in the Shenandoah Valley. In addition, Sherman (with one hundred thousand men), who now assumed Grant’s old command, would focus on Georgia, where he faced Joseph Johnston (with sixty-five thousand troops). Nathaniel Banks would lead a campaign in Louisiana on the Red River. But these auxiliary campaigns in March, April, and May came to nothing. Grant would go to Virginia and face Lee without the help these actions, had they been successful, would have provided.

Whatever impact Union losses in peripheral battles such as Olustee in Florida, Poison Springs in Arkansas, and Fort Pillow in Tennessee had on Northern morale, reports of atrocities committed by rebels against black troops in these engagements shocked the North. At Fort Pillow, on April 12, forces under Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest murdered dozens of men after they surrendered. In his report three days later, Forrest wrote, “The river was dyed with the blood of the slaughtered for two hundred yards.” Lincoln rejected outright retaliation, but the administration continued to refuse any exchange of prisoners unless black soldiers received equal treatment. And Union soldiers found ways to retaliate. After a battle in Mississippi, a lieutenant wrote, “We did not take many prisoners. The Negroes remembered ‘Fort Pillow.’ ”

The prisoners-of-war issue became especially controversial when Northerners learned of the abhorrent conditions at Andersonville Prison in Georgia. Opened in February, by the summer the camp population swelled to over thirty thousand. Men had no shelter, very little food, and water only from a polluted stream. The soldiers, one Union prisoner wrote, were “walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin.” Thousands died from disease and malnutrition. One soldier who kept a diary wrote on August 22 that “the men dys verry fast hear now from 75 to 125 per day.” After the war, Henry Wirz, a Confederate commander in charge of the prison, was tried for murder and executed. Through the spring, the Confederates continued to refuse equal treatment of black soldiers, and Grant became convinced that as Confederate forces diminished in strength it might be best not to exchange rebels, who would in all likelihood only return to the fight. By war’s end, 194,000 Union and 215,000 Confederate soldiers had been held as prisoners, resulting in 30,000 Union and 26,000 Confederate deaths.

Grant hoped his Virginia offensive, known as the Overland Campaign, would take many more prisoners. On May 5–7, the first battle took place at the Wilderness, some seventy square miles of forested terrain in central Virginia. During two days of brutal warfare in dense woods, Union forces suffered nearly eighteen thousand casualties and the Confederates eleven thousand. Had Grant withdrawn, it would have been a Confederate victory. Instead it was a tactical draw, with Grant determined still to push onto Richmond. On May 11, he informed Lincoln: “I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.”

The telegram came in the midst of fighting at Spotsylvania Courthouse. Lee had time to build up his defenses with logs and earthworks. The fight, which pulsated over two weeks, included a span of twenty-two hours where the forces engaged in hand-to-hand combat at a location called the “Bloody Angle.” Bodies piled several deep filled the trenches, and men shot and stabbed one another both through and over the fortifications. The rifle fire was so furious that it felled a sturdy oak tree. One Confederate called it “a Golgotha of horrors.” In the end, the Union suffered eighteen thousand casualties and Confederates twelve thousand. But Grant simply disengaged and continued his attempt to outflank Lee and threaten Richmond.

Grant’s Overland Campaign culminated on June 3, when he ordered a frontal assault at Cold Harbor against Lee’s well-fortified men. Union soldiers, who had survived Spotsylvania, knew what to expect. Some pinned their names to their uniforms so that their bodies could be identified afterward. They never made it to the entrenchments. In an hour, seven thousand were killed or wounded, compared to fifteen hundred rebels. Fighting would continue sporadically for a few more days, but Grant gave up on taking Richmond directly and now set his sights on Petersburg, a crucial rail junction south of the capital. In two months, the Army of the Potomac had lost almost two-thirds the number of men it had lost in the previous three years combined. Following days of operating on the wounded, John G. Perry, a Union surgeon, exclaimed, “War! War! War! I often think that in the future, when human character shall have deepened, there will be a better way of settling affairs than this of plunging into a perfect maelstrom of horror.”

The defeat at Cold Harbor came at a politically precarious time for Lincoln. Any number of rivals, including his own secretary of the treasury, Salmon P. Chase, were angling for the Republican presidential nomination in 1864 (the party called itself the National Union Party to make clear its purpose). A bitter John C. Fremont, the Republican candidate in 1856, aggrieved over having been relieved of his command, emerged as the candidate of a group of radical Republicans. Other names surfaced, including Benjamin Butler. Some mentioned Grant as a candidate. In addition to the factionalism within the Republican Party, Lincoln had to worry about the Peace Democrats and keeping the support of so-called War Democrats, who favored seeing the contest through to its end. This was no easy task. Democrats in general, whether for continuing to prosecute the war or demanding immediate peace, constituted a significant percentage of voters in the North. In the election of 1860, counting only those states that remained in the Union, Lincoln won 47.2 percent of the votes and the two Democratic candidates 46.6 percent.

While some nationally prominent Republicans may have challenged Lincoln, governors and others attuned to grassroots sentiment successfully promoted him as the people’s choice. At the national convention held in Baltimore from June 7–8, delegates unanimously renominated the President. On hearing the news, he said, “I will neither conceal my gratification, nor restrain the expression of my gratitude, that the Union people, through their convention … have deemed me not unworthy to remain in my present position.” The platform approved of the government’s refusal “to compromise with rebels, or to offer them any terms of peace, except such as may be based upon an unconditional surrender,” and at Lincoln’s behest, endorsed a constitutional amendment that “shall terminate and forever prohibit the existence of slavery within the limits of the jurisdiction of the United States.”

Such an amendment, the Thirteenth, was already in the works. On January 8, the first of several proposals came forward, and the Senate Judiciary Committee resolved differences in language to present an amendment that stated “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude” shall exist in the United States. On April 8, the Senate passed the measure, by a vote of 38 to 6. The House voted twice but failed in February and again in June to muster the necessary two-thirds majority. Passage of the amendment would have to wait until after the presidential election.

Whereas Lincoln’s emancipation policies faced opposition from both War and Peace Democrats in Congress, his reconstruction policies were challenged by radical Republicans. On July 2, Congress hastily passed the Wade-Davis Bill. Sponsored by Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio and Representative Henry Winter Davis of Maryland, the bill offered a more stringent approach to reconstruction than the president’s. Under its terms, 50 percent of the eligible voters had to take an oath of allegiance; only those who could take an “iron-clad oath” that they had never supported the rebellion would be enfranchised; and a constitutional convention would have to be held before state officials could be elected. Lincoln pocket vetoed the measure. He refused to be “inflexibly committed to any single plan of restoration,” not to mention one that differed from his own, and he would not repudiate the progress already made by Arkansas and Louisiana under the presidential plan of reconstruction.

Furthermore, he refused to “declare a constitutional competency in Congress to abolish slavery in States”; on this he had been consistent throughout. Instead, he hoped for eventual passage of a constitutional amendment. On August 5, Wade and Davis issued a manifesto in response to Lincoln’s veto: “a more studied outrage on the legislative authority of the people has never been perpetrated,” they averred.

Through the summer, Union efforts in the war went little better than they had in the spring, leaving Lincoln even more vulnerable politically. On June 18, the Army of the Potomac lost an opportunity to take Petersburg when Lee managed to reinforce his entrenched position. Union forces suffered eight thousand casualties and settled in for a siege of the city. Weeks later, they filled a mine shaft they dug beneath Confederate defenses and exploded it, creating a huge crater. But in the ensuing battle the Union corps under Burnside was beaten back. The siege of Petersburg would continue.

Matters fared no better in the lower South, where Sherman had begun his Atlanta campaign, in which he would face off against Joseph E. Johnston and his Army of the Tennessee. Before it was over, at least nine separate battles would be fought in addition to countless skirmishes. But at places such as New Hope Church and Pickett’s Mills in May, and Kennesaw Mountain in June, Confederate forces repulsed Sherman’s army. The frontal assaults that so devastated the Army of the Potomac had the same effect on the military division of the Mississippi.

Despite these successes, Confederate leaders grew unhappy with Johnston, who seemed, like McClellan, not to want to fight. On July 17, Davis relieved him of command and replaced him with John Bell Hood. Only thirty-three years old, Hood was wounded at Gettysburg, where he was beaten at Little Round Top. In September, another wound led to the amputation of his right leg. It would fall to the aggressive Hood, who had to be strapped into his saddle, to defend Atlanta.

In the heat of the summer, it seemed as if the war was stalemated. A year had passed since Gettysburg and Vicksburg, and still the Confederates—undermanned, undernourished, undersupplied—fought on, and not just defensively. In early July, Confederate infantry and cavalry under Jubal Early crossed the Potomac for a raid on Washington itself. He reached the outer fortifications of the capital, defended by additional troops hastily recalled from Meade’s army. Although Early had to retreat to Virginia, at the end of July his cavalry burned the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where residents refused to pay a $100,000 ransom.

These developments further depressed morale in the North and gave sustenance to the peace movement, which called for an end to the war under conditions to be negotiated. “What a difference between now and last year!” wrote a visitor to Philadelphia, “No signs of any enthusiasm, no flags; most of the best men gloomy and despairing.” Even Horace Greeley joined the chorus, declaring, “Our bleeding, bankrupt, almost dying country also longs for peace.” Lincoln tried to maintain a public face of good cheer and abiding faith, but in July one visitor described him as “quite paralyzed and wilted down.” One critic said, “He does not act or talk or feel like the ruler of a great empire in a great crisis. … He is an unutterable calamity to us where he is.” Lincoln came to believe that he would lose the election in November. On August 23 he prepared a memorandum that he asked his cabinet to sign without reading. It stated: “This morning, and for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards.”

Several days later, the Democrats meeting in Chicago nominated McClellan for president. Since being removed by Lincoln in November 1862, he had lived in New Jersey, writing reports defending his military service and making contact with Democratic leaders. His opposition to Lincoln on issues of emancipation and states’ rights remained as vociferous as ever. In his letter of acceptance, McClellan declared that “the preservation of our union was the sole avowed object for which the war commenced. It should have been conducted for that object only. … The Union is the one condition of peace—we ask no more.” The party platform, however, written in part by no less than Clement Vallandigham, placed peace before union, proclaimed the war a failure, and suggested that after hostilities were halted a “Convention of States” would determine the basis of the “Federal Union of the States.” McClellan was a War Democrat forced to run on a peace platform, a combination that could prove untenable.

Republicans such as Gerrit Smith, a founder of the Liberty Party, a social activist and philanthropist, and one of the secret six who had supported John Brown, denounced McClellan’s nomination. Calling the Democratic Party “neither more nor less than the Northern wing of the rebellion,” he ridiculed McClellan’s “pathetic appeal for the votes of soldiers and sailors. What an impudent affectation in him to profess regard for these brave and devoted men, whilst he worms his way up to the platform in which the cause they are battling, bleeding and dying for is condemned and its abandonment called for.”

That appeal worried Lincoln and the Republicans, who knew how loyal the men were to the chivalrous McClellan (“No general could ask for greater love and more unbounded confidence than he receives from his men,” wrote one officer) and feared the soldiers’ vote in the field (eighteen states allowed it, out of which twelve counted the vote separately; only Illinois, Indiana, and New Jersey forbade it) might help swing the election McClellan’s way. Fall was approaching, and the Union needed something to help turn momentum its way.

It arrived on September 3 in the form of a telegram from Sherman: “Atlanta is ours, and fairly won.” In a campaign that began in May, Sherman’s men had fought multiple battles around Atlanta from July onward. The Union commander’s strategy was to cut off Hood’s supply lines, but repeated attempts failed. Starting on July 20, for weeks, Sherman’s artillery bombarded the city, much of whose population of twelve thousand had fled. “I doubt if General Hood will stand a bombardment,” wired Sherman on July 21, but stand it he did. Sherman intensified the effort, bringing in from Chattanooga eight large siege guns. Sherman intended to “make the inside of Atlanta too hot to be endured.” Finally, in late August, Sherman moved against Hood’s railroad supply lines. One of his soldiers explained the general’s tenacity this way: “Sherman dont know the word Cant.” When Confederate soldiers failed to stop the Union forces at Jonesborough, Hood had no choice but to evacuate Atlanta.

The news that Atlanta had fallen revived Northern morale and Lincoln’s chances for reelection. The Chicago Tribune declared, “The dark days are over. We see our way out.” The New York Times said that “the skies begin to brighten. … The clouds that lowered over the Union cause a month ago are breaking away. … The public temper is buoyant and hopeful.” George Templeton Strong, in his diary, effused, “Glorious news this morning—Atlanta taken at last.”

The fall of Atlanta brought to Confederates a reality they did not want to face. The Richmond Enquirer called it a “stunning blow.” A North Carolina planter confessed, “never until now did I feel hopeless,” and a soldier in Lee’s army wrote, “I am afraid that the fall of Atlanta will secure Lincoln’s re-election.”

In addition to news of Atlanta’s capture, Lincoln had received word that Admiral Farragut had managed to overcome heavy fire from two forts and dodge a minefield and sail into Mobile Bay, giving the Union control of the waterway and isolating Mobile. Lincoln was so overjoyed by the double-shot of Mobile and Atlanta that, on September 3, he issued a Proclamation of Prayer and Thanksgiving. He called for “devout acknowledgement to the Supreme Being in whose hands are the destinies of nations” and set aside the following Sunday for thanksgiving to be “offered to Him for His mercy in preserving our national existence against the insurgent rebels who so long have been waging a cruel war against the Government of the United States, for its overthrow.”

More success for the Union cause came in September and October, with Philip Sheridan’s campaign through the Shenandoah Valley. Embarrassed by Jubal Early’s raid on Washington, Grant created the Army of the Shenandoah and put Sheridan in command. He won a stirring victory on September 19 at Opequon Creek and another at Fisher’s Hill three days later. On October 19, after Jubal Early surprised the Union at Cedar Creek, Sheridan launched a counterattack that almost destroyed the Confederate army in the area. Union command had learned that the war was as much about resources as men, and just as cutting supply lines in Atlanta had led to victory, so now Sheridan wreaked havoc on the rich farmland of the valley that sustained Lee’s army. He reported, “I have destroyed over 2,000 barns filled with wheat, hay, and farming implements; over seventy mills filled with flour and wheat; have driven in front of the army over 4,000 head of stock, and have killed and issued to the troops no less than 3,000 sheep.” He said he would leave the valley “with little in it for man or beast.” Mary Chesnut, the wife of former South Carolina senator James Chesnut and an inveterate diarist, spoke for many Southerners when she wrote, on hearing news of Sheridan’s exploits, “Thew stories of our defeats in the valley fall like blows upon a dead body. Since Atlanta I have felt as if all were dead within me.”

More good news came Lincoln’s way. Not only were military actions succeeding but political initiatives as well. In September, Louisiana, in response to Lincoln’s plan for reconstruction, adopted a new state constitution and abolished slavery. Maryland followed suit, its voters approving a new constitution on October 13, to take effect November 1. And three new states had been added to the Union—Kansas in 1861, West Virginia in 1863, and Nevada in 1864, states that would add to his electoral total. Early returns from state elections also boded well: it seemed that Republicans were winning and that the earlier momentum of Democrats calling for peace had been staunched.

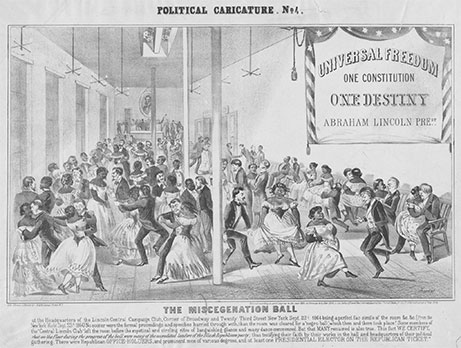

The election campaign through the fall turned nasty. Opponents attacked Lincoln personally and suggested that if he was reelected blacks and whites would mingle freely across the nation. A new word was coined, miscegenation, to describe a supposed mixing of the races that would necessarily follow a Republican victory. One political caricature, titled “The Miscegenation Ball,” showed interracial couples dancing and talking in a hall with a portrait of Lincoln and a banner reading “Universal Freedom. One Constitution. One Destiny. Abraham Lincoln PREst”

9. In the election of 1864, Republican opponents sought to stoke Northern fears of racial intermingling, and this caricature depicts blacks and whites dancing together. A portrait of Lincoln hangs over the stage. The word miscegenation was coined in the lead-up to the election.

Democratic race-baiting failed to carry the Northern electorate. On November 8, the nation learned that Lincoln had been reelected by an overwhelming margin. He won 55 percent of the popular vote. In the electoral college, he took 212 votes and carried 23 states. McClellan won 21 electoral votes and 3 states: New Jersey, Maryland, and Kentucky. The soldier vote also went overwhelmingly for Lincoln. He won at least 78 percent of the votes that were separately counted. One soldier, from the Eleventh Iowa Infantry, reported, “Our regiment is strong for Old Abraham—three hundred and fourteen votes for Lincoln and forty-two for McClellan”—these men were not about to vote against continuation of the war and the honor of their fallen comrades. The president would continue in office come March, but with a new vice president, Andrew Johnson, a prominent war Democrat who had been serving as military governor of Tennessee since March 1862.

On November 10, Lincoln stood before a crowd that had come to serenade him. Now that it was over, he said that the election, even with all the strife, “has done good too. It has demonstrated that a people’s government can sustain a national election, in the midst of a great civil war. Until now it has not been known to the world that this was a possibility. … We can not have free government without elections; and if the rebellion could force us to forego, or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us.”

Elation among Lincoln’s supporters reached unprecedented heights. Diarist George Templeton Strong declared, “the crisis has been past [sic], and the most momentous popular election ever held since ballots were invented has decided against treason and disunion.” A sergeant in the 120th New York, who had lost a son and a brother-in-law, proclaimed the election “a grand moral victory gained over the combined forces of slavery, disunion, treason, tyranny.” And Charles Francis Adams Jr., in the Union cavalry, wrote to his brother in London, “This election has relieved us of the fire in the rear and now we can devote an undivided attention to the remnants of the Confederacy.”

Those remnants tried publicly to put on a brave face. The Richmond Examiner said, “the Yankee nation has committed itself to the game of all or nothing; and so must we.” But they couldn’t fail to notice how peaceably even Lincoln’s staunchest opponents reacted to the election. Grant wired “no bloodshed or rioit [sic] throughout the land.” Lee had warned Davis in September that “our ranks are constantly diminishing by battle and disease, and few recruits are received; the consequences are inevitable.” And now the ranks thinned even further with desertion and a sense of hopelessness filtering in. Women wrote asking their husbands and sons to come home, and many of them complied, knowing how severely the war effort had transformed the lives of mothers and daughters who had been forced to take over the responsibilities of running plantations and farms. On November 18, a dispatch from Lee read “desertion is increasing in the army despite all my efforts to stop it.”

Despite the devastating losses, Davis and Lee remained resolute. Lincoln informed Congress in his annual message of December 6: “the war continues.” He added that “the most remarkable feature in the military operation of the year is General Sherman’s attempted march of three hundred miles directly through the insurgent region.” He left Atlanta on November 15 with sixty-two thousand men for a 285-mile trek to the seaport city of Savannah. His aim was not so much to engage in combat as to destroy resources and sap the will of a hostile people. “We cannot change the hearts of those people in the South,” he said, “but we can make war so terrible … [and] make them so sick of war that generations would pass away before they would again appeal to it.” Sherman divided his army into three columns and told Grant that he would “make Georgia howl.”

Sherman’s army cut a sixty-mile swath across Georgia. On leaving Atlanta, they set a fire that ended up destroying one-third of the city, and they kept up the burning as they marched toward the sea. Sherman’s official orders called for widespread foraging, destruction of mills and cotton gins, confiscation of all animals, and the liberation of any able-bodied slaves who could be of service. He explicitly ordered that “soldiers must not enter the dwellings of the inhabitants, or commit any trespass,” but those orders often went disobeyed as stragglers unattached to the army wreaked havoc. One soldier recalled, “We had a gay old campaign. … Destroyed all we could not eat, stole their niggers, burned their cotton & gins, spilled their sorghum, burned & twisted their R. Roads and raised hell generally.”

On December 21, Sherman captured Savannah, a week after a detachment of the Union Army of the Tennessee destroyed what was left of John Bell Hood’s forces in a battle at Nashville. Sherman wired Lincoln that he had a present for him, to which the president responded, “many, many thanks for your Christmas gift—the capture of Savannah.”

On Christmas Eve, Sherman wrote to Henry Halleck: “We are not only fighting armies, but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies. I know that this recent movement of mine through Georgia has had a wonderful effect in this respect. Thousands who had been deceived by their lying papers into the belief that we were being whipped all the time, realized the truth, and have no appetite for a repetition of the same experience.”

Earlier in the spring, Jefferson Davis tried as best he could to arouse the Confederate nation against the remorseless war brought to their land: “plunder and devastation of the property of non-combatants, destruction of private dwellings and even of edifices devoted to the worship of God, expeditions organized for the sole purpose of sacking cities, consigning them to flames, killing the unarmed inhabitants and inflicting horrible outrages on women and children are some of the constantly recurring atrocities of the invader.” This was before Atlanta and before Sherman’s march. Davis could do little but watch the Confederate armies continue to melt away (“two-thirds of our men are absent,” he wrote).

Wars begin in an instant, but they conclude slowly. The end would take a few more months, and in those months more lives would be lost. But both sides now sensed it was nearly over.