Chapter 6

1865 and after the war

On January 11, 1865, Robert E. Lee wrote a letter that would have been unthinkable three years earlier. He began by asserting the slaveholder’s common view that the relationship between master and slave was “controlled by humane laws and influenced by Christianity and an enlightened public sentiment.” He did not want to disturb that relationship, but the course of the war required that the Confederate Congress consider recruiting slaves as soldiers. Lee pointed out that the Union already was using slaves against them, leading in time to a destruction of the institution anyhow. “We must decide,” he concluded, “whether slavery will be extinguished by our enemies and the slaves be used against us, or use them ourselves at the risk of the effects which must be produced upon our social institutions. My opinion is that we should employ them without delay.” He knew that a promise of freedom would have to accompany enlistment, and he was willing to make it so as to prolong the war.

The idea of slaves fighting for the Confederacy had been broached previously, but always rejected. Most Southerners agreed with Howell Cobb, former congressman from Georgia and a leading Confederate, who argued: “You cannot make soldiers of slaves or slaves of soldiers. The day you make a soldier of them is the beginning of the end of the Revolution. And if slaves will make good soldiers, [then] our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” Lee, in his letter, tried to offset this belief, arguing that slaves “can be made efficient soldiers.” But decades of proslavery ideology that insisted that slaves were docile and happy-go-lucky could not be overturned in a season.

The war compelled Southern women, as well as men, to reconsider their attitudes toward slavery they relied on yet at times also deprecated. Typical of the intellectual gyrations of aristocratic planters, one Georgia belle confessed, “I have sometimes doubted on the subject of slavery. I have seen so many of its evils chief among which is the terribly demoralizing influence upon our men and boys but of late I have become convinced the Negro as a race is better off with us as he has been than if he were made free, but I am by no means so sure that we would not gain by his having his freedom given to him.” As for arming slaves, she thought it “strangely inconsistent” to offer emancipation to blacks who fought “to aid us in keeping in bondage a large portion of his brethren,” whereas “by joining the Yankees he will instantly gain the very reward” of freedom.

Nonetheless, on March 13, Davis signed a bill that allowed for the enlistment of slaves. That the Confederate Congress passed such an act, however narrowly, speaks perhaps to the strength of Confederate nationalism, to a desire to establish an independent Confederacy even without the very institution, slavery, that these states had left the Union to protect in the first place. Thomas Goree, Longstreet’s aide-de-camp, put the matter this way: “We had better free the negroes to gain our independence than be subjugated and lose slaves, liberty, and all that makes life dear.”

By the time the Confederacy acted on this issue, the Union had done something more direct and complete to assure the abolition of slavery. With the reelection of Lincoln as a mandate, on January 31 the House passed the Thirteenth Amendment by a vote of 119 to 56, only two votes over the two-thirds needed. Lincoln personally involved himself in the legislative process, believing its passage “will bring the war, I have no doubt, rapidly to a close.” Before the amendment was submitted to the states for ratification, Lincoln signed it, even though constitutionally he did not have to. In the meantime, both Missouri and Tennessee adopted new state constitutions that abolished slavery.

Few were yet thinking about the contours of postemancipation life for Southern blacks when Sherman, on January 16, issued Special Field Order Number 15, which provided that “the islands from Charleston south, the abandoned rice-fields along the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the St. John’s River, Florida, are reserved and set apart for the settlement of the negroes now made free by the acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States.” Each black family was promised up to forty acres of tillable land. Sherman’s order led to the settlement of some forty thousand blacks on confiscated and redistributed land. But by year’s end, a new president would revoke the order as reconstruction policy began taking shape.

Whereas Sherman acted alone with Lincoln’s permission, Congress took its first steps toward thinking about the former slaves when, on March 3, it passed the bill that created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, known as the Freedmen’s Bureau. The Bureau, run by Major General Oliver Otis Howard, supervised relief efforts, furnishing clothing, medicine, and food to the freedmen as well as destitute whites. It also helped with the effort to create schools and churches and supplied legal support to help resolve conflicts over labor contracts and prevent fraud. Originally intended to also oversee leasing and sales of abandoned and confiscated property to the freedmen, the bureau provided land to only some thirty-five hundred blacks before being ordered to restore the property to its original owners. Preparing for the social revolution embedded in the transition from slavery to freedom would require much effort, but first the war had to be brought to a close.

On February 3, three Confederate commissioners—Vice President Alexander Stephens, John A. Campbell, a former Supreme Court justice, and R. M. T. Hunter, president of the Confederate Senate—boarded the River Queen at Hampton Roads and met with Lincoln and Seward. Peace balloons had been sent up previously, most notably when Horace Greeley met with Confederate agents at Niagara Falls in July 1864, but they had all popped for one reason or another: Lincoln insisted on the abandonment of slavery as a precondition, and Davis insisted on using the language of peace between “two countries.” Lincoln had not seen his old friend Stephens for sixteen years. As the men talked, it became clear that they could not agree on terms, and as Lincoln reported to Congress, the conference “ended without result.”

A month later, on March 4, he was inaugurated for his second term. It rained all morning, but the sun shined through as Lincoln rose to speak. In a brief address, Lincoln offered his view of the origins of the war, never referring to the Confederates as anything but “insurgents.” He acknowledged that “both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish.” He devoted much talk to God, noting that both sides “read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. … The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes.” Lincoln, whose generosity of spirit allowed him to forgive easily, concluded: “with malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”

The military victories continued to come. Fort Fisher had fallen in January, giving the Union control of Wilmington, North Carolina, and cutting Lee’s supply line. On April 2, after two days of battle that exacted more than ten thousand casualties combined (seven thousand of them Confederate), Lee ordered the evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond. On April 4, Lincoln visited Richmond with his son Tad. As he walked from the waterfront, thousands of blacks gathered in celebration. “I know I am free for I have seen Father Abraham and felt him,” declared one woman. He made his way to the Confederate White House, where he sat in Jefferson Davis’s study. He then went to the state house. A meeting with a small delegation of Confederates came to nothing, and he returned to Washington after a stop at army headquarters. On April 7, having heard of Sheridan’s success, Lincoln wired to Grant: “Gen Sheridan says ‘if the thing is pressed I think Lee will surrender.’ Let the thing be pressed.”

After exchanging messages with Grant, on April 9, Robert E. Lee and his aide rode to Appomattox Courthouse to surrender. Lee had no choice. Any further combat would decimate the Army of Northern Virginia. And he refused to resort to a guerilla war that allowed swarms of his men to continue to fight a partisan battle on their own. The generals met around two o’clock in the afternoon at the home of Wilmer McLean, who ironically had moved there on fleeing Manassas after the first battle of Bull Run. Lee dressed in his finest uniform and wore a sword; Grant was muddy and had on a worn blouse as a coat. They discussed terms, and Grant generously offered not only to parole the army of twenty-eight thousand as long as men did not take up arms again but also to allow them to return home and keep their horses. An hour later, it was over. As news spread among the troops, cheers went up. “To have seen us,” recalled one Union private, “no one would have supposed that for four long years we had been involved in a deadly war.” “The war is over,” Grant was reported to have said. “The rebels are our countrymen again, and the best sign of rejoicing after the victory will be to abstain from all demonstrations in the field.” Grant provided rations for Lee’s starving men, who had plenty of bullets left but no biscuits. By June, the other Confederate armies had surrendered and Jefferson Davis was in prison.

Lincoln thought about how best to restore the union quickly. Retribution was not in his makeup. In what turned out to be his final speech, he signaled support for giving black men the right to vote. He continued to joust with radical congressmen in his own party, and he listened to the opinions of his cabinet members. He often recalled his dreams, and after meeting with Grant to hear a firsthand account of what transpired at Appomattox, he told of one in which he was in a vessel and “moving with great rapidity towards an indefinite shore.” On April 14, Good Friday, in the afternoon before going to the theater, he took a carriage ride alone with his wife. He was joyous and cheerful. He told her, “I consider this day, the war, has come to a close.”

Despite being urged not to go out that evening, Lincoln assembled a party of four to see Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre. Arriving late, he was resoundingly cheered as the orchestra played “Hail to the Chief.” During the third act, John Wilkes Booth made his way to the presidential box. A prominent actor, the Maryland-born Booth supported the Confederacy and despised Lincoln as a tyrant and tool of the abolitionists. He was among the crowd on April 11 who had heard Lincoln endorse giving the vote to “very intelligent” blacks “and those who serve our cause as soldiers.” “That means nigger citizenship,” exclaimed Booth, swearing, “This is the last speech he will ever make.” He contrived a plan to assassinate Lincoln, Johnson, and Seward, with the help of his henchmen, who had earlier plotted to kidnap the president and whisk him off to Richmond. The assault on Johnson miscarried; Lewis Powell repeatedly stabbed the bedridden Seward, but he survived; Booth shot the president in the head, leapt down to the stage and cried “Sic semper tyrannis”—“Thus always to tyrants.” Lincoln was carried across the street and placed on a small bed in a narrow room. He lingered for nine hours, and then reached the indefinite shore of which he had dreamed.

On April 16, Grant received a letter of condolence from Confederate general Richard Ewell. The officer wrote to assure Grant of Southern “feelings of unqualified abhorrence and indignation for the assassination of the President of the United States. … No language can adequately express the shock produced upon myself, in common with all the other general officers confined here with me, by the occurrence of this appalling crime, and the seeming tendency in the public mind to connect the South and Southern men with it.”

“The public mind,” in Ewell’s apt phrase, knew not what to think, convulsed with sorrow in the North over the loss of Lincoln and in the South over the loss of the war. Shockingly, six weeks after the assassination, Andrew Johnson sought to implement his own restoration plan. Lincoln had first started thinking about reconstruction as early as 1863. His ideas developed over time and often collided with the markedly different ideas of radical Republicans. Little was settled except that the United States would be one and that slavery would be abolished. But under what terms would the states that had seceded regain their place? And how would Southern society navigate its journey from slave labor to free labor? Looking beyond a structural reconstruction of the nation, one Union officer confessed: “How are we to woo this people back to their old love for the Union is a mystery to me.”

Andrew Johnson wasted little time announcing his policies. With Congress out of session, he issued a proclamation that provided for amnesty and the restitution of property, except for slaves, to Southerners who took an oath of allegiance. The proclamation made exceptions of certain categories of Confederate officeholders and officers, as had Lincoln’s proclamation, and added anyone owning more than $20,000 of taxable property. Johnson had risen from poverty, and he held deep animosity toward planter aristocrats. He was the only Southern senator to remain in the Union when secession came, and his activities as a prowar Democrat and a military governor of Tennessee won him a spot on Lincoln’s ticket. But like many Democrats, although he denied the legitimacy of secession, he supported states’ rights generally. A former slaveholder, he also shared in the dominant racial ideology of his day.

Through the summer, under terms set by Johnson, constitutional conventions met and repudiated secession as well as the Confederate debt and ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, a condition for readmission. It was ratified on December 6 when Georgia approved it, the twenty-seventh out of thirty-six states to do so. And Johnson took great personal satisfaction from having thousands of members of the Southern elite come groveling for a special pardon.

Congress would not come into session until December. While some Republicans initially favored Johnson’s lenient policies, radical Republicans such as Thaddeus Stevens were outraged by an approach that, in the end, would actually give the South additional congressional representation. Stevens sought the enfranchisement of blacks, an action opposed not only by Johnson but also by several Northern states, including Connecticut, which in the fall defeated a state amendment giving black men the vote.

On September 7, Thaddeus Stevens delivered a speech in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in which he offered his views on the work of reconstruction, or restoration as Johnson preferred to call it. The duty of the government, Stevens proclaimed, was to punish the “rebel belligerents, and so weaken their hands that they can never again endanger the union.” To help accomplish this he insisted that “the property of the chief rebels should be seized and appropriated to the payment of the national debt caused by the unjust and wicked war which they instigated.” Stevens lambasted those who argued that since secession was unconstitutional the states had never actually left the Union and therefore they could not be treated as having forfeited their place. But then how, he wondered, might any reconstruction ever take place? “Reformation,” he insisted, “must be effected; the foundation of their institutions both political, municipal, and social must be broken up and relaid, or all our blood and treasure have been spent in vain … the whole fabric of Southern society must be changed.” The rebel states should be treated as conquered territories, de facto alien enemies, and the some seventy thousand “proud, bloated, and defiant rebels” should pay for what they had put the nation through.

Johnson’s “restoration” versus Stevens’s “reformation” marked the grounds for the battles over reconstruction. Through the fall, under Johnson’s terms, constitutional conventions gathered in Southern states, and these states held elections in anticipation of being quickly restored. But Congress had different ideas, and when the Thirty-ninth Congress began its work in December, members refused to seat Southern representatives. Instead, they created a joint committee to discuss reconstruction policy. The committee called witnesses and heard testimony about what was taking place on the ground in the former Confederacy. What they discovered would lead them to consider civil rights legislation and propose what would become the Fourteenth Amendment.

Republicans in Congress were especially alarmed at the reports of Southern actions directed at blacks. States such as Mississippi and South Carolina passed stringent codes that discriminated against the freedmen. These included vagrancy laws and annual employment contracts aimed at limiting the movements of blacks. The codes also forbade blacks from serving on juries, stipulated harsher punishments for crimes than those given to whites, and outlawed interracial marriage. The Freedman’s Bureau was in a position to help protect blacks, but Johnson, in one of the first acts that would lead him into open warfare with Congress, on February 19, 1866, vetoed a bill to extend the life of the Bureau on the grounds that it was not constitutional. In July, Congress passed a new bill, over Johnson’s veto, extending the life of the Bureau and creating Freedman’s Courts to help protect black rights.

Johnson also vetoed a civil rights bill passed by Congress on March 13. The bill defined persons born in the United States as citizens and guaranteed them “full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the Security of person and property.” Even the bill’s supporters recognized how transformative it was. By committing federal authorities to protecting the rights of its citizens, it redefined the role of the government. One senator, who supported the measure, admitted that “this species of legislation is absolutely revolutionary. But are we not in the midst of a revolution?”

Not only was the bill passed over Johnson’s veto; Congress, partly in response to the so-called black codes just mentioned, went about drafting and debating a new constitutional amendment, the Fourteenth, which would further protect civil rights. Section 1 defined all persons born in the United States as citizens and guaranteed them that no state law “shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens” or deprive any person of life, liberty, or property “without due process of law” or deny any person “equal protection of the laws.” Section 2 set the terms for the apportionment of representation and, rather than give blacks the vote, simply reduced Southern representation. Section 3 prohibited anyone from holding office who had previously taken an oath to support the Constitution and then “engaged in insurrection or rebellion.” Section 4 renounced the Confederate debt and confirmed the validity of the federal debt. On June 13, 1866, Congress submitted the amendment to the states. Every Republican in the House voted for it; every Democrat was opposed.

Abolitionists, who had been pressing for black suffrage, were keenly disappointed by section 2, which supported, implicitly at least, the rights of states to curtail voting on racial grounds. Thaddeus Stevens well understood that the amendment could not be everything he might have desired. Why do “I accept so imperfect a proposition?” he asked rhetorically. “I answer, because I live among men and not among angels.”

One congressional act Johnson did sign was the Southern Homestead Act. Enacted on June 21, it opened up forty-six million acres of public lands across the South (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi) to settlement and development. It differed from the Homestead Act of 1862 in that one could not purchase the land outright. The Act also made clear that blacks and whites were equally eligible. Oliver Howard expressed the optimism of many that this act would go a long way toward providing a solution to the problem of the transition from slavery to freedom. He said, “there is no reason why the poor whites and freedmen of the South cannot take advantage of the present homestead law, and enter a career of prosperity, that will secure them fortunes, elevate them socially and morally, and settle the many vexed issues that are now arising.”

It didn’t turn out as Howard had hoped. Much of the land made available was of poor quality, and timber companies, through fraud, snatched up the premium acreage. The poor whites and blacks most in need of land were also the ones who did not have means to travel to the land or subsist while working it. Blacks also faced resistance from whites who feared losing a pool of wage laborers and did not want them to own their own property. A petition by a group trying to gain land in Florida asked Congress “to provide for our race such transportation, rations, building materials, tents, surgeons & surveyors and such legislation as will secure among ourselves honesty, industry and frugality and deliver us from the fear of all who maliciously hate and persecute us.” Such material relief, however, was not forthcoming.

The fall elections promised to serve as a referendum on presidential versus congressional reconstruction. Andrew Johnson took the unprecedented measure of embarking on a speaking tour to win support for his policy of reconciliation. Instead, he drove prospective conservative and moderate voters away with harangues that branded his opponents traitors and even suggested that providence had played a role in making him president. Race riots in Memphis in May and New Orleans in July gave the lie to Johnson’s optimistic vision of a loyal South ready for readmission: the mob in New Orleans attacked delegates to a convention on black suffrage and murdered thirty-seven blacks. If anything, it seemed as if the embers of rebellion were about to reignite. Republicans dominated the election, both nationally and locally. Even in the Upper South, a new group of Unionists supportive of black civil rights gained power.

Legislators did not wait for the new members to be seated. On March 2, 1867, the Thirty-ninth Congress passed the First Reconstruction Act over Johnson’s veto. The Act divided Confederate states into five military districts and made them subject to military authority, each commanded by a general. It also made state governments only provisional. When these states adopted a new constitution enfranchising black males and ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, they would then be readmitted. Johnson vetoed the Act as exceeding congressional authority. Congress also sought to check presidential autonomy by passing the Tenure of Office Act, which prevented Johnson from removing any executive branch officials whose appointment had required Senate confirmation.

It didn’t take long before Johnson challenged this Act. On August 1, he suspended Edwin Stanton, the secretary of war, who supported congressional plans of reconstruction. Much to the chagrin of Republicans everywhere, Grant stepped in as interim secretary. He did so to support not Johnson but the military command in the South. Johnson removed several military commanders he thought too radical, including Philip Sheridan and Daniel Sickles. When the Senate refused to uphold Stanton’s suspension, Grant vacated the office, and Stanton returned. On February 21, 1868, Johnson removed Stanton. Three days later, the House impeached him.

The trial began on March 30. Senator Charles Sumner supported conviction as “one of the great last battles with slavery. … Slavery has been our worst enemy, murdering our children, filling our homes with mourning, and darkening the land with tragedy; and now it rears its crest anew with Andrew Johnson as its representative.” But other senators warned against setting a dangerous precedent such that one party with an overwhelming majority could oust the president if he was a member of the opposite party. Lyman Trumbull feared that

Blinded by partisan zeal, with such an example before them, they will not scruple to remove out of the way any obstacle to the accomplishment of their purposes, and what then becomes of the checks and balances of the constitution, so carefully devised and so vital to its perpetuity? They are all gone. In view of the consequences likely to flow from the day’s proceedings, should they result in conviction on what my judgment tells me are insufficient charges and proofs, I tremble for the future of my country.

In May, the Senate voted, and Johnson escaped conviction by one vote.

By then, Republicans had realized that the current of public opinion was turning against them. Democrats had gained seats in state elections the previous year, carrying New York and Pennsylvania. And in Ohio and Minnesota, Democrats rallied to defeat ballot referendums for black male suffrage. Outside New England, black men in the North could not vote any more than freed slaves in the South.

On July 9, the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified, but it seemed that the promise of constitutional protection for all citizens only increased opposition and extralegal violence against some of them. New derogatory words entered the language: “scalawag” for Southerners who supported the Republicans and “carpetbagger” for Northerners who came south to help the freedmen. The Ku Klux Klan had been founded in Tennessee in June 1866, originally as a private social club, but it quickly morphed into an organization whose members were rabid opponents of Republican politics and black equality. Led by former Confederate officers, including Nathan Bedford Forrest, who had been responsible for the massacre at Fort Pillow and now served as “Grand Wizard” of the white-hooded secret society, the Klan claimed tens of thousands of members. Through the fall of 1868, they murdered white and black Republican leaders, terrorized the freedmen, and burned homes and schools. One journalist, touring the South after the war, observed: “The real question at issue in the South is not ‘What shall be done with the negro?’ but ‘What shall be done with the white?’ … The viciousness that could not overturn the nation is now mainly engaged in the effort to retain the substance of slavery. What are names if the thing itself remains?”

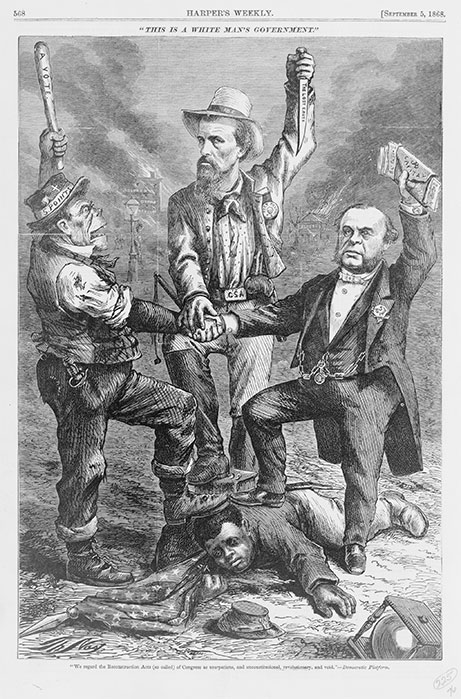

During the presidential campaign of 1868, Thomas Nast, whose work for Harper’s Weekly during and after the war helped sustain the cause of radical Republicans, offered one of his most searing indictments of the Democratic Party in his cartoon “This is a White Man’s Government.” Three men are standing on a prostrate black Union veteran. On the left, a caricature of the working-class Irishman whose handiwork at the Colored Orphan Asylum during the draft riots hangs in the background; in the middle, Nathan Bedford Forrest, whose belt buckle reads “CSA” (Confederate States of America), his knife, “the lost cause,” and medal “Ft. Pillow”; on the right is New York financier August Belmont waving money with which to buy votes. With the American flag and his Union cap lying at his side, the fallen man stretches toward the ballot box, just out of reach.

On accepting the Republican nomination for president, Grant closed with the words “Let Us Have Peace.” His election victory over New York’s Horatio Seymour showed a narrow margin in the total vote—3 million to 2.7—but a comfortable win with 53 percent of the vote and an Electoral College victory of 214 to 80.

10. Thomas Nast’s cartoon portrays the powerful forces that combined to deprive the freedmen of their rights as citizens.

In eight states, however, the margin of difference in the popular vote was less than 5 percent. It was enough to make Republicans realize that though they had won the war, they might be losing the peace. Because they felt it was both right and politically expedient, Congress in February 1869 approved the Fifteenth Amendment, which stated that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Black men would be guaranteed the vote, and they would no doubt vote for the party of Lincoln. It was an astonishing accomplishment, whose rapidity left observers breathless. The radical abolitionist Parker Pillsbury observed that “suffrage for the negro is now what immediate emancipation was thirty years ago,” and yet unlike emancipation it was achieved quickly.

The Fifteenth Amendment became law in March 1870, but Grant’s administration faced the problem of how to protect the expansion of the franchise against efforts by the Klan and others to keep voters from the polls. Congress in short order passed several Enforcement Acts, intended to prevent election fraud and “enforce the rights of citizens of the United States to vote in the several states of this union.” They also passed the Ku Klux Klan Act, which sought to suppress the Klan’s terrorist activities through arrests and prosecutions and authorized the president to suspend habeas corpus in areas of insurrection.

In many respects, 1870 marked the end of reconstruction. By that year, every state had been readmitted to the nation. In fact, all but three (Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia) had been readmitted by June 1868 (Georgia was admitted, then excluded again, and then readmitted in 1870 with the other states). By 1871, Congress had passed whatever legislation it was going to generate to support the freedmen and help reconstruct the South, and the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments were signed into law.

But if political reconstruction was over, economic reconstruction continued. It took the South decades to recover its output of cotton, rice, and sugar—in 1870 production stood at about two-thirds of that in 1860. Per capita income in the South continued to fall, from three-quarters to one-half the national average. Even though some individuals continued to have vast landholdings, the plantation as an economic center began to break down. The freedmen’s initial response to emancipation was to assert autonomy by moving away from the master’s house. Most blacks preferred small farms to plantations and quickly became embedded in various forms of land tenancy. They would often rent the land in return for cash or a share of their crop. These arrangements differed depending on what the landlord provided, and inevitably from season to season black farmers as well as white found they were always in debt, placing them in a cycle of always borrowing against future crops.

With slavery ended, there was a need for labor in the South, and a struggle ensued to make fair agreements between former planters, now landlords, and former slaves, now freedmen. Republican newspapers published letters reputed to be from ex-slaves negotiating for a fair deal. For example, Jourdon Anderson wrote to his former master, who wanted him to return to work for him:

We have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you. This will make us forget and forgive old scores, and rely on your justice and friendship in the future. I served you faithfully for thirty-two years and Mandy twenty years. At $25 a month for me, and $2 a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to $11,680. Add to this the interest for the time our wages has been kept back and deduct what you paid for our clothing and three doctor’s visits to me, and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. … If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past we can have little faith in your promises in the future.

In reality, few freedmen found fair deals. Indeed, they lost not only their economic but also their political independence as states passed assorted measures—literacy tests, residency requirements, poll taxes—aimed at keeping blacks from exercising the suffrage. One visitor to the South after the war offered a cogent analysis of the reasons for suppression. He said that white Southerners “admit” that the government has set the slaves free, but they “appear to believe that they still have the right to exercise over him the old control. … They cannot understand the national intent as expressed in the Emancipation Proclamation and the Constitutional Amendment. I did not anywhere find a man who could see that the laws should be applicable to all persons alike; and hence even the best men hold that each State must have a negro code.” Blacks, concluded one Southern lawyer, have “freedom in name, but not in fact.”

The most significant progress for freedmen came through educational efforts. Many Northerners flocked south to teach, and many Southern black institutions of learning emerged: Fisk (1866), Morehouse (1867), Hampton (1868). The use of federal and state funds, as well as private philanthropic contributions, produced a startling result: literacy among black teenagers rose from 10 percent in 1865 to over 50 percent by 1890. Schools of industrial labor, designed to provide training in mechanical arts and trades that would enable youth to earn a livelihood, were especially widespread. One such school, the Manassas Industrial School, opened on September 3, 1894. Frederick Douglass, celebrating on that day the fifty-sixth anniversary of his escape from slavery, delivered the dedication address and told the assembled crowd that

to found a school, in which to instruct, improve and develop all that is noblest and best in the souls of a deeply wronged and long neglected people, is especially noteworthy. This spot once the scene of fratricidal war, and the witness of its innumerable and indescribable horrors, is, we hope, hereafter to be the scene of brotherly kindness, charity and peace. We are to witness here, a display of the best elements of advanced civilization and good citizenship. It is to be a place where the children of a once enslaved people may realize the blessings of liberty and education, and learn how to make for themselves and for all others, the best of both worlds.

But aside from tacit support of educational efforts, most Northerners had grown weary of the whole subject of reconstruction, seeking to heal what one writer called “the wounds and diseases of peace.” In 1872, the Amnesty Act restored officeholding rights to many former Confederates. In 1873, a financial panic seized America, and many politicians and activists turned their attention away from the problems of the South. With the election of 1874, Democrats gained control of the House. In 1875, the Supreme Court, in United States v. Cruikshank, ruled that only states, not individuals, were subject to federal prosecution for violating the constitutional rights of individuals. Since local authorities rarely tried to protect the freedmen, those who terrorized them could now act with impunity.

“Let us have done with Reconstruction,” pleaded one New York newspaper in April 1870, “the country is tired and sick of it.” From that point on, another phase, redemption—the restoring of conservative Democratic leadership to the states that had made up the Confederacy—proliferated. By 1875, nearly every state had shaken off Republican rule. The war had been over for ten years, and so, too, the desire to settle its outcome.

By then, Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner had penned their summary statement about the tectonic shifts occasioned by the Civil War: The United States was saved, now singular and not plural, never again to be threatened seriously by disunion, though the tensions between state and nation in regard to the locus of authority would continue to resonate. Slavery was abolished, and the freedmen had obtained constitutional rights guaranteed to them by the federal government, though in most other ways their struggle to define the contours of freedom and achieve equality had only just begun. A powerful, centralized national government used the tools at hand to extend further a dynamic capitalistic ideology that would develop markets and commercial interests at home and abroad. Southern society was left devastated as wealth in property was entirely lost or devalued, cities were destroyed, shipping and rails were immobilized, livestock were slaughtered, and production was decimated. A generation of white males aged fifteen to thirty-nine participated in the war, and one out of three was left dead or wounded: With so much death (360,000 Union and 260,000 Confederate), romance, an ideal characteristic of the decades before the carnage, yielded to realism—a faith in facts and an understanding that life entailed an ongoing battle for survival.

The process of settling the conflict persisted well past 1875. Both sides continued to live with their memories of war, and both sides made use of it. Northerners would “wave the bloody shirt” to remind voters of the Union dead, and Southerners would craft a cult of “the lost cause,” a belief that the Confederacy stood for a gallant and glorious endeavor. As new generations came of age, they couldn’t possibly understand what the country had been through and what the soldiers had experienced. In July 1913, on the golden anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, thousands of white veterans, federal and rebel, walked the terrain again, gathered together, and reminisced. For both sides, the past would never end, and with the mist of nostalgia heavy in the air, they would seek to recapture and remake it.