![]()

With his trip to Paris fast approaching, the ATAC analyst was elated. He would be meeting Israel’s espionage master-mind, Rafael “Rafi” Eitan. After leaving Mossad at the behest of his good friend Ariel Sharon, Eitan had served as the head of LAKAM. He had also been the counterterrorism adviser to Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir. Working for Eitan would be the thrill of a lifetime. Unbeknownst to Pollard, the legendary spymaster who had been responsible for capturing Eichmann would soon be making history again, and Pollard would play a role in it.

Still cautioning him not to let Anne know anything, Pollard’s handlers also told him that he would have to wed her because Judaism did not condone common law marriage. So, in November 1984, the two lovers traveled to Paris with plans to buy an engagement ring. They checked into a suite at the Paris Hilton International that cost three hundred dollars a day. Little did Sella know that Pollard’s fiancée was not only aware of the operation, but she had also given it her personal stamp of approval.

Sapphire and diamond ring worn by federal agent for evidence photo —NIS PHOTO

The day after Pollard and Anne arrived, the colonel phoned them at the Hilton. It was decided that Sella’s wife would take Anne shopping while he and Pollard prepared for the meeting with Eitan.1 The two men went over classified items Pollard was providing to the Israelis, reviewed background information on Syrian MiG pilots training in Russia, and discussed the effect on the balance of power in the Golan Heights if Syria were to deploy a certain type of missile.2

Afterwards they met the women for lunch at the hotel, then went to Mappin and Webb, a jewelry store on Place Vendome, to look at a ring Anne had seen earlier in the day. The ring, with a two-carat sapphire surrounded by two carats’ worth of small diamonds, cost ten thousand dollars.3 Anne had fallen in love with it, but Pollard said he couldn’t afford it.

Luxuries were showered on the couple during their stay in Paris. The operation was anything but subtle. That evening the two couples went on a dinner cruise, and at one point a roving photographer, without asking permission, took pictures of them together. Furious because it would compromise the operation if the press got a picture of him and Pollard together, Sella ripped the camera out of the photographer’s hands and seized the roll of film.4 Instead of being inconspicuous, the novice spies were attracting still more attention to themselves.

The colonel was upset, and not just about the photographer. Apparently, Eitan wanted to assign someone else as Pollard’s handler. For the second time, Sella asked Pollard to intervene. Would he talk with Eitan, try to convince him not to make this switch? Again, Pollard agreed.

Several days into the trip, while Anne went shopping again, Sella took Pollard to meet Eitan. The ride from the Paris Hilton took about thirty minutes and they ended up in a residential area with lots of apartment buildings. For some reason Pollard was under the impression that the apartment he and Sella visited belonged to an elderly German couple, but no doubt it was an Israeli safe house used to meet undercover operatives. Yosef Yagur, who had long wavy hair and dark, penetrating eyes, met them at the door and introduced himself, using only his first name. Pollard followed him into the living room and there he was, seated in a chair, the legendary spymaster. He was a short, chubby man, balding, with a pleasant smile and thick glasses that magnified his eyes.

Pollard crossed the room and held out his hand. “You’re one of us,” Eitan said, shaking it. He told Pollard that the material he was providing Israel was vital to its survival.5

After a small ceremony during which Pollard was sworn in as an Israeli citizen—there was no documentation to make it official—he was handed a detailed briefing paper on the forces arrayed against Israel in the Middle East. The document, in Hebrew and classified TS, appeared to Pollard to have come from an Israeli prime minister’s briefing paper.

Eitan leaned forward in his chair with an intent look and began questioning his guest. Did the CIA have any dirt on Israeli cabinet members? Any psychological studies on them? Could Pollard identify any Israeli “rats” working in the country? Did he know anything about the Syrian order of battle? Pollard didn’t answer these questions.

Their conversation consumed the entire morning. Following a catered lunch, Eitan discussed the “essential elements of information” that Israel wanted Pollard to obtain—documents, for example, pertaining to Soviet aircraft, air-to-air missiles, and surface-to-air missiles, and any chemical and biological weapons in Arab hands, including neutron bombs. One item the Israelis were keenly interested in was the so-called radio signal notations manual or RASIN manual. This was a roadmap to signal intelligence that described America’s global listening profile, geographic slice by geographic slice. At the time, however, the Israelis didn’t quite know what it was or where it came from. Pollard’s handlers wanted the spy to locate and copy the most up-to-date edition. Pollard said he would try to find out what it was and who had originated it.6

Over the next few days several more meetings took place. Repeatedly, Pollard was told that he would be “taken care of” if apprehended by U.S. authorities. Eitan assured him that the U.S. response would be “contained,” in other words, the United States would take no action because of the close relationship between the two countries. Pollard, Eitan reiterated, was “one of them.”

The spymaster directed Pollard to provide passport photos of himself and Anne. They were Israeli citizens now, the spymaster said, and he wanted to make everything kosher.7 The name on Pollard’s passport would be Danny Cohen, after the famous spy Eli Cohen, who in the 1960s had gone undercover to Damascus and was later executed by the Syrians. Pollard was on cloud nine. Cohen—it was a name to be proud of, the name he would use after the operation when he moved to Israel.

The Israelis told Pollard that they were going to buy Anne her engagement ring. Sella had gone back inside the jewelry store and convinced the shop owner to reduce the price by three thousand dollars. Still, it was clearly expensive, and not yet purchased. They needed to make up a story so that no one would wonder how Pollard, on his salary, could afford the ring. Pollard came up with a subterfuge about an Uncle Joe Fisher, the black sheep of a family of diamond brokers in Europe. He dictated a fake letter from Uncle Joe to Anne, and Sella scribbled it down on Hilton letterhead stationery. In the letter Uncle Joe said he was sorry that he wouldn’t be able to attend Pollard’s wedding, and that he was sending the engagement ring as a gift to Anne. He ended the letter saying, “I hope that this ‘surprise’ will make up for my absence. Wear it in good health! Your Uncle, J. Fisher.” Anne, the Israelis told Pollard, was to carry this letter with her at all times to prove who had given her the ring, in case she was asked. She would not actually receive it until after returning to the United States.8

During the meetings the Israelis also provided Pollard with basic training—just the bare bones. For example, if he was ever asked to take a government polygraph exam, he should resign his position first. Pollard didn’t need to be told twice about that. The last thing he wanted was to endure another polygraph. He hadn’t told the Israelis he had already taken two, neither of which turned out well.

Again he was assured that Israel would take care of him if he were ever caught. He could escape by way of the Israeli embassy in Washington, they said. But they never provided Pollard with a plan—not even the most basic countersurveillance techniques, none of the instructions he would need to get out of the United States in a hurry, no code words to use when calling his handler to implement an escape, no secondary contact numbers in the event he couldn’t get in touch with his handler. Without realizing it, Pollard would be left out in the cold.

Eitan, like Sella before him, expressed little interest in the terrorist and counterterrorist information that Pollard had persisted in supplying to the Israelis. They already had sufficient information on that subject, they reiterated; Pollard shouldn’t waste his time.

When the topic of Pollard’s new handler came up, the American urged Eitan to reconsider and keep Sella on. He was comfortable with Sella, Pollard argued. But Eitan was adamant that he be cut out. He told Pollard that the colonel had some important matters to tend to at his airbase and that he had to be “isolated” from the operation. End of discussion. Pollard had been led to believe that his new handler lived in Israel, but he now found out that Yagur was in fact the scientific attaché to the Israeli consulate in New York City. In the future, when they had meetings in Washington, Yagur would be arriving from the Big Apple, not Israel. Eitan wanted the two men to continue having operational meetings in Europe, but Pollard disagreed, saying the navy special security officer might get suspicious about all his trips overseas.

To reimburse him for this first trip to Paris, the Israelis gave him approximately ten thousand in cash. Eitan also established Pollard’s “salary”: fifteen hundred a month, a figure based on his navy pay.9 The figure was woefully below what Pollard had hoped for, but the Israelis didn’t want him to have too much unexplained cash. They knew the FBI looked at unexplained or sudden affluence as an indicator of espionage. Despite their concern, they did not provide Pollard with any training on how to conceal his extra earnings.

After leaving Eitan with an itinerary, Pollard and his fiancée departed Paris and traveled around Europe for three weeks, staying at luxury inns. Their hotel charges alone exceeded four thousand dollars, and the restaurant bills, as they ate their way through France, Italy, Austria, and Germany at four-star establishments, were equally high. With all the fine dining and little exercise, Pollard started to put on weight. His belly now protruded over his belt, his cheeks were chubby. He was sporting a mustache and his hairline had receded, which made him look older and more mature.

Back in the States, Pollard and Anne played fast and loose with their extra cash, blowing it mostly on food, drink, and drugs. They were living the good life now. Neither seemed to realize the gravity of the step they had each taken or the consequences should they be discovered. Instead of lying low, Jonathan and his fiancée were virtually advertising their crimes to the world.

As for Sella, he was none too pleased about being replaced as Pollard’s handler. In the coming months he would maintain frequent contact with the spy in America’s capital, but only socially. Neither could have predicted that the colonel who had launched Pollard’s clandestine career would eventually play a key role in its termination.

Once the three-week European vacation ended, Pollard returned to spying. During one of his next deliveries to the Israeli diplomat’s residence in Potomac, he was given the ring purchased for Anne in Paris, along with the letter from “Uncle Joe” to carry with her at all times.

The DIA was one of the facilities hardest hit by Pollard, his “gold mine.”10 He spent a lot of time in its central library, which stored all Defense Attaché Office messages and other intelligence reports, including military intelligence from the Middle East and around the world. Pollard combed this repository and took whatever he wanted, meaning everything he could carry out at any one time.

The normal procedure for analysts who wanted specific classified documents from the DIA library was to fill out a certified request form and send it to the library, which would arrange to have the documents ready for pickup. But Pollard wasn’t interested in just a few specific documents. In his search for as much information as possible, he skipped the request forms and hunted for documents himself. He would stroll into the library, scan the computer system for defense attaché officers’ reports from Baghdad, Damascus, Riyadh, Cairo, Algiers, and Pakistan, pull up the reports on the computer, copy them, and put them in his briefcase with no audit trail. Unlike intelligence information reports, TS and SCI documents were available only in hard copy, and Pollard had to sign them out. For these, he would complete a check-out form and drop it off at the desk before exiting the building. No one ever verified what he had in his briefcase. Because of his courier card he was never challenged. If it was too late to return to his office, he would store the material at his apartment.11

Another of Pollard’s methods was to retrieve messages from the Special Intelligence Communications (SPINTCOM) center in the basement of NIS headquarters. He would order material from his computer terminal upstairs in the ATAC. Once the center obtained the material, they would call and tell him it was ready for pickup. As at the DIA library, he had to sign for TS and SCI material. After doing so, he would return to his office and place the material in a drawer until he had enough to transfer into a sturdy briefcase that could hold at least four to six reams of paper.

Sometimes, in a single day, Pollard would make two or three trips to his car, a 1980 Ford Mustang with a fold-down backseat that gave him access from inside the vehicle to the trunk, where he kept a suitcase. On occasion he drove over to Sam’s Car Wash in Suitland, right outside the back gate of the NISC (from which he also removed information). While the vehicle went through the wash cycle, he transferred material from his briefcase into the suitcases in the trunk. On other occasions Pollard would find a secluded park in Maryland and transfer the documents into his suitcases. If he were taking material from the SCI libraries at the DIA, he would park in a secluded area on Bolling Air Force Base to transfer it.

In his quest for highly classified information, Pollard was an expert at deceit and manipulation. Early in the operation when the Israelis wanted to get their hands on intelligence about the joint Egyptian-Argentine Condor missile, he called an acquaintance at his former place of employment, the NISC, who steered him toward a DIA analyst who happened to have information on the subject. After contacting this person by phone, Pollard visited him at DIA headquarters.

As a cover story, Pollard told the DIA analyst that the NIS was working on a technology-transfer case involving an Egyptian missile engineer who was approaching U.S. companies on the West Coast looking for information. Without questioning Pollard or verifying his comments, the DIA expert provided him with a complete, highly classified folder on the Condor and even showed him where to find the copy machine. Pollard would later claim that the Israelis had been aware merely that Egypt was attempting to build a medium-range ballistic missile. They wanted him to fill in the gaps.12

Wednesday, 23 January 1985, would be one of Pollard’s last drops at Ilan Ravid’s residence in Potomac, but he didn’t know that yet. Still feeling elated from his trip to Paris two months earlier, he wanted to make a big impression. Following his previous drop-off at the house, he had continued to collect highly classified information for almost two weeks and had stored it in the ATAC. He was supposed to make the delivery on 21 January, but that evening he and Anne, along with some friends, attended an inaugural ball for President Ronald Reagan at the Shoreham Hotel.

At about 6:00 PM on Tuesday, 22 January, Pollard drove back to his office, knowing everyone had left for the day except two ATAC watch standers. His office was located on the second floor of the NIC-1 building, which also housed NIS headquarters. The security setup and layout in the SCI facility were flawed, allowing Pollard easy access. The area was supposed to be highly secured, but classified material did not have to be locked up. Sometimes it would accumulate several feet high and be left for the night, stacked on the floor or under analysts’ desks. The two watch standers stood duty on the far side of the ATAC, answering phones and gathering intelligence reports from classified computers. Pollard’s cubicle was located at the other end of the center. There were two doors into the ATAC, one near the watch standers, another at the far end through which Pollard could enter. His cubicle was no more than twenty feet from this door, separated from it by a small office and adjoining space, and the watch standers wouldn’t be able to see him enter and exit because their view was obstructed by cubicle partitions.

Pollard was determined to remove every document he had stacked up in his work area during the previous two weeks. He segregated the messages from TS/SCI publications, which had to be signed out and returned. Carrying either his briefcase or a box stuffed to the gills, Pollard hauled the material down the corridor to the elevator and rode it to the first floor, then walked past the security guard and out to his car parked near the entrance to the building. Once in a while he would go and strike up a conversation with the watch standers, in case they were growing curious.

The security guard at the front desk did present a slight problem. The courier card authorized Pollard to remove classified material without a search, but to get back into the building after each trip to his car he had to ring a doorbell, it being after hours. The guard would have to get up, leave his small office, and open the door. To alleviate the problem, after a couple of trips Pollard informed the guard he was moving material from NIC-1 to NIC-2—the building next door—for a project he was working on. Pollard was lucky. The security guard didn’t want to keep getting up to open the door, so he put a block down between the frame and the door to prop it open.

Pollard made some fifteen to twenty trips to his car, filling five suitcases to the brim. It took him nearly five hours to complete the task. Just before 11:00 PM, he finished and went home.13 The security guard never made an entry into the logbook about Pollard’s unusual actions that night, nor did he notify his relief. Security was lax, procedures were ignored; no one had the common sense to harbor suspicion.

On 23 January Pollard made his drop-off at Ravid’s house. Ravid, Yagur, and a third person whom Pollard had never met were there. The Israelis had already had a taste of what their operative could produce in volume; this time, the spy had outdone himself. Two suitcases contained TS- and SCI-coded publications that Pollard had to return on Monday morning, and right away the Israelis attacked those, pulling out the documents and running upstairs to copy them. The other three suitcases held highly classified messages that didn’t have to be returned. At this meeting his handlers provided the analyst with two black leather briefcases in which to carry additional documents.

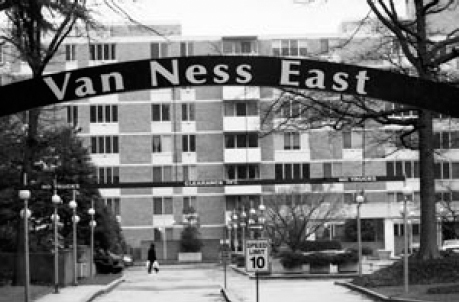

Van Ness Apartments, Washington, D.C. —SHANNON OLIVE

Up to this point the Israelis had felt fairly secure using Ravid’s residence, but the material being passed was so voluminous and highly classified that they decided it would be prudent to choose a new temporary drop-off location. Irit Erb, who worked as a secretary at the Israeli embassy, had a place in the Van Ness Apartments at 2939 Van Ness Street N.W., not far from the embassy. Her apartment was quickly outfitted with a high-speed Xerox machine, and Yagur instructed Pollard to drop material off there in the future. After being furnished with keys to Erb’s garage and apartment, in the event she wasn’t home, Pollard began drop-offs every other Friday evening, unless there was a publication or a message he felt the Israelis needed ASAP.14

During his next encounter with Yagur, Pollard was introduced to an Israeli agent referred to as Uzi. Eitan had decided Uzi would soon be taking Yagur’s place as Pollard’s handler. The analyst never learned Uzi’s real name. They needed a meeting place other than Erb’s apartment, Yagur and Uzi said. The embassy had asked an American-Israeli lawyer who lived in Israel to purchase an apartment for embassy business. One was purchased in the Van Ness complex for $82,500.15

This new apartment was equipped with several sophisticated high-speed copying machines, and Erb began photocopying material there during weekends. Pollard would typically deliver the classified documents to Erb’s apartment on a Friday evening. Erb would copy or have copied the documents for which Pollard was accountable, in order that he could retrieve them, usually on Sunday, for return to their classified repositories the following Monday. Materials such as messages or cables which Pollard was not accountable for were left with Erb.16 On the last Sunday of every month, Yagur would fly or drive from New York and meet with Pollard at the newly purchased apartment to give him his monthly salary of $1,500 and to issue new instructions.

It was at one of these meetings that Pollard complained about his compensation. The work he was doing for Israel was dangerous, he argued, and the quality of the information he provided was better than anything Israel had ever seen through intelligence exchanges with the United States. He wanted more money. Unbeknownst to Pollard, the Israelis had already decided to raise his salary but they hadn’t told him. How much? Yagur wanted to know. “Up it by a thousand,” Pollard replied.17 Yagur passed the request on to Eitan and it was approved. Now Pollard would start receiving $2,500 a month.

During this same meeting, the issue of the radio signal notations (RASIN) manual resurfaced. The only thing Pollard had been able to find out was that the manual dealt with extremely sensitive signal intelligence. Later, at a meeting in February 1985, Yagur showed him a copy of the first chapter of the manual. After looking it over, the analyst realized it was an NSA document. According to Pollard, Yagur told him that using this first chapter the Israelis had been able to access the uplink of the Soviet Military Assistance Group in Damascus, and that they “needed the whole manual to see if it was economically and technically feasible to decrypt the uplink signals.”18

How did the Israelis get their hands on the first chapter of the RASIN manual? This question, and the fact that the Israelis were asking for documents by exact title, sometimes even by identification number, later led U.S. investigators to suspect that there had been someone else besides Pollard passing information to Israel. The news media would dub this mystery figure Mr. X, but his existence has never been proven. Still, the hypothesis raises interesting questions that persist to this day.