![]()

It was just a matter of time before the analyst was discovered. Even spies who are trained in their craft and possess the utmost discretion run the risk of arrest. Pollard had neither training nor discretion.

The man who can be credited as the first both to notice Pollard’s suspicious activity and to take it seriously enough to follow through by reporting it was a coworker of the analyst’s who did not want his name revealed. To this day, few know his identity. During an interview I had with him, I didn’t ask why he wanted to retain his anonymity. It was none of my business, and besides, I understood that without a guarantee of anonymity, much suspicious activity in the intelligence community would never be reported. At any rate, he is a true hero, the only person I know of in the whole sordid saga of Jonathan Jay Pollard who had the courage and patriotism to come forward and report that something “was out of the ordinary and just didn’t seem right.” This chapter is his story, and the story of the dedicated supervisor to whom he reported.1

On Friday, 8 November 1985, shortly before 5:00 PM, Pollard’s ATAC coworker wasn’t feeling well. He decided to go home a few minutes early. Just before leaving the office, he spotted Pollard holding up a list of document titles attached to the front of an envelope. The envelope contained TS/SCI message traffic he had just retrieved from the SPINTCOM center in the basement. The messages, as always, were double wrapped and sealed with brown masking tape. Pollard was telling some other analysts how stupid he was for requesting all the wrong documents from the center downstairs. He was upset; now he had to go back downstairs to the computer room and destroy the documents.

An ATAC analyst could order TS and SCI material from a special computer with links to all intelligence agency networks, military or civilian. Once the requested documents had been gathered, a SPINTCOM employee would call the analyst to say they were ready for pickup. The analyst would then go downstairs to the computer room, show his or her credentials and courier card, sign for the messages, and pick them up. An analyst who was finished with a TS/SCI document had to sign it back in. Most of the time returned material was destroyed under the two-person rule; that is, the person who ordered the material would have someone witness it being shredded, then sign a notice verifying that it had been destroyed.

Naval Investigative Service (NIS) Headquarters, Suitland, Maryland. —NIS/FBI AERIAL PHOTO

The coworker wasn’t paying much attention to Pollard. He left the ATAC, got into his car, which was parked directly across from NIS headquarters, and waited for his wife, who happened to work in an office nearby.

While waiting, he observed Pollard’s wife drive into the half-circle parking lot and pull up directly in front of the entrance to NIS headquarters and the NIC-1 building. She got out of the car and set off toward the building when, suddenly, Pollard emerged from the lobby and came down the steps to meet her. In his hand was an envelope sealed with brown masking tape, just like the one he had been complaining about a few minutes before.

The coworker thought to himself that Pollard could never have gone down to the computer center in the basement and destroyed the material so fast. This must be the same package. Where was he taking it? Thinking the analyst was probably going to drop it off at another intelligence agency, the coworker was about to blow it off. Then Pollard got into the car with his wife and headed away from the NISC. Maybe he’s going to the DIA, the colleague thought. But Pollard’s car turned in the opposite direction.

On the drive home with his wife, who also had a security clearance, the coworker told her what he had witnessed and voiced his suspicion. All kinds of crazy ideas were running through his head. Why had Pollard’s wife picked him up? Would he show the material to her, or worse, to a foreign country? Should he report what he had seen? And if so, to whom? If he told someone, his name might be brought up during an investigation. What if he was wrong and falsely accusing Pollard of something he hadn’t done? What if the word spread throughout headquarters and he was labeled a snitch? His colleagues would no longer trust him. He would be shunned, and risked losing his job.

Then he began to rationalize his coworker’s actions, coming up with excuses. What if Pollard had been authorized by his supervisor to take the classified material somewhere? Pollard would never commit a security violation. Stop overreacting, he told himself.

While he agonized over the matter, his wife listened. Finally, she told him that if he felt so strongly there was something wrong, he needed to report it. Although still fearful that his suspicion might be unfounded or not believed, he decided to call his supervisor, Commander Agee, when he got home.

Before being promoted to commander of the ATAC, Jerry Agee had been assigned to the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean. In 1983 he was off the coast of Lebanon analyzing the terrorist intelligence reports that streamed in from across the region. He had also recruited military personnel from Communist countries for collection operations.

The coworker made up his mind not to tell Agee exactly who it was he had seen. This would prevent a lot of embarrassment if he were wrong. All he would say was that he had seen someone take something out of the building, it was late in the afternoon, and the person did not head in the direction of one of the intelligence agencies. No big deal.

Back at home, he phoned Commander Agee, hoping he was still at work. When Agee answered the phone, the coworker cautiously told him the story of what he had seen. Agee asked him who the person was, and when he didn’t respond, the commander said jokingly, “Was it Ron Brunson?” referring to a hardworking analyst in the ATAC who also happened to be a prankster. The coworker didn’t think it was funny. Suddenly it dawned on him that by withholding the name he might force Agee to start a witch-hunt that would eventually blow up in his face. He had no choice. It was Jonathan Pollard, he admitted, then pleaded with Agee to conceal his identity. He was anguishing over this, he said, afraid he might be accusing Pollard of something he hadn’t done. Agee told him not to worry.

In an attempt to get this resolved quickly, the coworker suggested, Agee might want to check Pollard’s office to see if there was a torn manila envelope in his wastebasket, on his desk, or somewhere else in his cubicle. That would indicate that Pollard had removed the material in the package and left it in his office rather than removing it from the building. If not, Agee might want to go downstairs to the Special Intelligence Communications center and see whether or not Pollard had returned the materials and had them destroyed. There was no getting around the fact that the coworker had seen Pollard take a package out of the building taped the way TS/SCI documents were always taped. He knew Pollard had classified information; he just didn’t know where he had taken it.

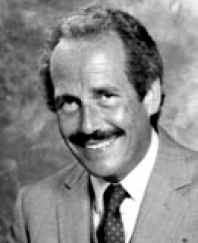

Jerry Agee. —RON OLIVE

Commander Agee thanked him and told him again not to worry; he would keep this to himself. While there might be a reasonable explanation for Pollard’s behavior, Agee had no doubt that the coworker had accurately reported what he had seen. He was not one to overreact in any situation.

As soon as he hung up, Agee took the elevator down to the communications center to see whether Pollard had picked up or returned some SCI documents that day. The logbook showed that the analyst had indeed picked up SCI message traffic at about 4:00 PM, but there was no indication that the documents had been returned or destroyed. He had signed out numerous lengthy messages, and their subject matter, interestingly, did not lie within his area of responsibility. The documents dealt with intelligence in the Mediterranean and the Soviet Union.

Commander Agee hurried back up to Pollard’s cubicle and began poking around, first checking his wastebasket for an empty manila envelope. Nothing. Nor was there a torn envelope on top of Pollard’s desk. He did notice some papers on the Middle East but didn’t think much about them. Next he checked the “burn bag,” used for disposal of classified information. When full, a burn bag is sealed and taken to a secure location awaiting transportation to the Pentagon. Once at the Pentagon it is deposited in an incinerator for destruction. There was no empty manila envelope in the burn bag. Then Agee glanced under the desk. Highly classified documents and message traffic were arranged in two-foot high stacks, but again, no envelope.

Back at his desk, Agee sat down and began to work through what he knew. Late in the day Pollard had definitely signed for highly classified materials whose subject lay outside his purview. They had not been returned and could not be found in or around Pollard’s desk. His immediate conclusion was that the ATAC employee’s report of events was probably true. Pollard had the security documents with him. Then the question was, why had he left with those materials, where were they, and why would he commit such an egregious security violation?

It was about eight o’clock on Friday night. Tired, Agee realized that he could have missed the materials during his quick search, or that Pollard could have locked them up in his safe. Should he simply call Pollard and ask him where the materials in question were? No, he quickly decided. First, Pollard was a notorious fabricator and unlikely to tell the truth, and second, it would give him the opportunity to return the materials quietly and claim they had never left the ATAC. Agee decided to wait until Tuesday (Monday would be Veterans Day) to approach Pollard, without telling him the source of the information. It was late. Tomorrow was Saturday and the commander was looking forward to a restful weekend.

On his way home to Annapolis, however, he couldn’t stop mulling over the problem of Pollard. The analyst’s behavior had been remarkably eccentric over the past year, and in spite of that he had been assigned to work the terrorism problem on the Americas desk at the ATAC. Although Pollard had requested an assignment to the Middle East desk, he was refused because he lacked the experience. Besides, another analyst already held that job. Was Pollard unhappy? He had been missing deadlines for reports, and his supervisor, Tom Filkins, had given him the verbal warning regarding his performance. Agee himself was upset with Pollard for being months behind in producing a paper on the Caribbean. Yet the analyst was obviously working diligently, out of the office a lot collecting materials and meeting with analysts at various intelligence organizations. On the other hand, if Pollard was going to such lengths to collect information, why would he delay writing up the Caribbean report?

When Agee finally made it home, his wife, Karen—also a naval intelligence analyst—asked why he had been delayed. He explained that he had a problem with one of his employees. A serious security violation might have occurred. She asked what “serious” meant.

Over a late-night dinner Agee laid out his concerns, and Karen’s “comments laid bare the issue he faced.” She was blunt about the need to pursue this further. Agee knew she was right, but the question still facing him was how.

Commander Agee couldn’t sleep that night. It was three o’clock in the morning and a gut feeling told him he needed to go back to work. So much for his restful three-day weekend. By five he was in his car and by six he was back in the ATAC. He asked the watch standers if they had seen the kind of manila envelope that held TS/SCI material discarded in the trash or lying around. No, they answered. And so Agee began a cubicle-by-cubicle search of the ATAC, looking in every trash can and burn bag, on top of and underneath every desk. He searched Pollard’s cubicle again. No envelope.

While in Pollard’s space Agee decided to check out the stack of highly classified documents, books, and message traffic he had noticed the night before. He started sifting through the material. To his shock, which swiftly turned to aggravation, he noticed little under Pollard’s desk that dealt with his area of responsibility. In fact, the material dealt almost exclusively with the Soviets, their missile systems, and the Middle East. It came from various intelligence agencies, but mostly from the DIA. In all, Pollard had thousands of pages of highly classified information. What is he doing? Agee thought angrily. The more he saw, the more questions he had.

Pollard was a strange bird. He said crazy things. He was missing deadlines and delaying production in the ATAC. Agee had caught him in lies. The analyst had been given a form to update his SCI clearance that was due in August. It was now November, and the form still hadn’t been turned in. What if Pollard had been removing messages? What if—no. Agee stopped in the middle of the thought. He feared something was wrong but couldn’t bring himself to admit it. Just like his employee had done the night before, Agee was rationalizing away his suspicions.

Returning to the communications center to determine just how much classified information Pollard had been signing for and what type of information it was, he confronted the staff member at the window. “I can’t tell you why I’m asking and you can’t say anything to anyone,” Agee told the sailor. He wanted a computer printout of the titles of everything Pollard had requested during the previous six months.

When Agee saw it, he almost did a double take. The list was incredibly long. Every week for six months the wayward analyst had been picking up message traffic packages, almost all coded TS or SCI, and almost all dealing with the Middle East and the Soviet Union. Just as significant, most of the packages were picked up on Fridays.

The ATAC commander’s stomach turned. Clearly, Pollard’s action of the previous Friday was not a random event but part of a deliberate pattern of behavior. Each Friday evening he probably took the classified material out of the facility. He has to be giving this stuff to somebody, Agee thought.

Kurt Lohbeck? About six months earlier Pollard had told Agee about the freelance reporter who was slipping over the mountains from Pakistan into Afghanistan, reporting on the Afghan insurgency against the Soviets. Pollard wanted permission to task Lohbeck with getting information about arms sales to the Afghans, but the ATAC commander said no and told him to discontinue his contact.

By now, Agee was convinced the Pollard affair was no simple security violation. It was much more serious than that—possibly even espionage.

As he gathered more data, Agee tried to piece together the evidence in a rational manner. The volume and nature of the materials Pollard had accumulated indicated more than a passing interest in the terrorist threat in the Middle East. In fact, the materials had to do with U.S. military operations in the Mediterranean and the latest Soviet weapon systems. In Agee’s analysis, although the Soviets were probably keen to know more about U.S. military activities in the Mediterranean, they wouldn’t be acquiring technical material on their very own systems. Moreover, many countries in the eastern Mediterranean possessed those same Soviet-produced systems. There was only one country that would have an interest in all the materials Pollard had in his possession, Agee thought. Yet that would be difficult, if not impossible, to prove.

The implications of an allegation would reach far beyond the U.S. Navy and its intelligence organizations. The manner in which the NIS handled this explosive situation was critical, Agee realized. He went back up to his office and, knowing he couldn’t keep this to himself until Tuesday, thought of calling Lanny McCullah, NIS’s assistant director for counterintelligence. At first he hesitated. After all, Agee was a commander in the navy. If he were wrong, his career could be over. For that matter, if he were right it could be over. Either way, he had to do something, and right away.

Lanny McCullah in memoriam. —PROVIDED BY DARLENE MCCULLAH

McCullah was an outstanding assistant director with broad experience in the intelligence community. He had worked for the Menlo Park, California, Police Department in the early sixties, and later as a special agent with the Office of Naval Intelligence. In his position with the NIS, he had sat on numerous intelligence committees and had testified before the House and Senate intelligence committees on policy recommendations and navy spy cases.

So, on a sunny Saturday morning in early November, Agee called to say he needed to discuss something with him that couldn’t wait. McCullah told Agee to drop by his house. Agee hurried over to McCullah’s suburban home, pondering how to break the news to him. Shortly after he arrived, they shared a beer on the back porch while Agee briefed him.

The two doubted that Pollard was actually engaged in espionage. What country could be so foolish as to recruit someone like Pollard, of all people?2 McCullah told Agee that on Tuesday morning he would brief Admiral Cathal Flynn, director of the NIS.

That weekend, neither Agee nor Pollard’s anonymous coworker could have realized the incredible events that were about to unfold. Had it not been for these two conscientious men, U.S. national security would have suffered an even more severe blow, and Jonathan Jay Pollard might have escaped to Israel without ever having to pay the price.