![]()

On 19 January 1987, before Pollard was sentenced, Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger submitted a forty-six-page classified memorandum to Judge Robinson detailing the havoc Pollard had wrought with U.S. intelligence. “Declaration of the Secretary of Defense”—commonly known as the Weinberger memorandum—carried a TS/SCI classification, and to this day most of its contents remain under wraps. The memorandum presented nineteen items illustrating the different types of TS/SCI material Pollard had passed on. These were selected out of hundreds of thousands of classified messages and documents gathered by Richard Haver’s damage assessment team at the Department of Defense.

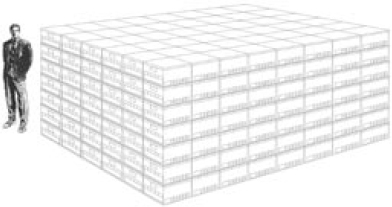

Because the Weinberger memorandum is classified, I cannot address its contents other than to say that the damage Pollard inflicted was colossal. The government estimated how much material he took based both on signature cards and on the signatures he wrote when requesting classified material from libraries, archives, and message centers throughout Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Virginia. Had Pollard gone to trial, the prosecutors would have been able to prove in court that in terms of sheer volume, the classified documents he removed measured at least 360 cubic feet—one million-plus pages delivered over the short period of eighteen months. Add to this the material he removed without a signature, and the total figure, though unknown, would be even more staggering.1 When presented with these findings, Pollard agreed they were probably accurate.

To put it into perspective, one has to remember that the Pollard case arrived on the heels of the Walker family spy case. Navy radioman John Walker had provided codes to the Soviets for intercepting and deciphering military transmissions. In the Department of the Navy’s damage assessment report to the presiding judge in the Walker trial, Rear Admiral William O. Studeman, the DNI at the time, wrote that “the harm caused by John Anthony Walker is of the gravest nature,” pointing out that during his eighteen years of spying he had enabled the Soviet Union to decipher more than one million messages.

Bankers boxes—visual representation of the sheer volume of classified documents—measured at least 360 cubic feet, one million-plus pages—Pollard provided to Israel over the short period of eighteen months —PETER BURCHERT

Mr. M. Spike Bowman, a well-respected military attorney who worked with the team assessing damage done by Pollard, told me that this case, breaking so soon after Walker’s, overwhelmed the Department of Defense. Among the documents compromised were detailed analytical studies containing technical calculations, graphs, and satellite photographs. Many of those studies were hundreds of pages long, including analyses of Soviet missile systems disclosing how the United States collected information. From these documents a reasonably competent intelligence analyst could infer the identity of human intelligence sources. Moreover, some analyses carried the author’s name. Disclosure of such specific information to a foreign power, even an ally of the United States, could have exposed American agents and analysts “to potential intelligence targeting.”2

According to Bowman, when the scope of the damage Pollard had inflicted became clear, Secretary of Defense Weinberger was beside himself. Before submitting his memo to Judge Robinson, he sent it back to the damage assessment team six times asking for harsher words to describe how gravely Pollard had compromised U.S. national security.

Pollard’s and Anne’s attorneys, Richard and James Hibey, were given access to the Weinberger memorandum—Anne, not being prosecuted for espionage, wasn’t allowed to see it—but first they had to sign a memorandum of understanding informing them of the sensitive nature of the documents and ordering them never to reveal their contents to anyone unless authorized.3 The defense team also had to read and sign a nondisclosure agreement and a security briefing acknowledgment, as well as to undergo special background checks.

In the unclassified portions of the document, Weinberger laid out how damaging it can be to the United States when classified information is disclosed to friendly powers without authorization. The harm can be as great as giving classified information to hostile powers because “once information is removed from secure control systems, there is no enforceable requirement . . . to provide effective controls for its safekeeping. . . . Moreover, it is more probable than not that the information will be used for unintended purposes. . . . [S]uch disclosures will tend to expose a larger picture of U.S. capabilities . . . than would be in the U.S. interest to reveal to another power, even to a friendly one.”4

Weinberger pointed out that the United States shares intelligence with friendly countries under exchange agreements made by high-level officials after carefully evaluating “the costs of disclosure to our national security versus the benefits expected to be obtained if disclosure is approved.” Pollard, he went on, personally confessed to and identified from memory more than “eight hundred classified publications and more than one thousand . . . classified messages and cables which he sold to Israel.” According to Weinberger, not one of the publications Pollard provided was authorized for official release to Israel, not even in redacted form.5

Those parts of the memorandum addressing the significance of Pollard’s disclosures and his compromised sources and methods were almost entirely censored. In a section on the risk to American personnel, Weinberger warned the court, “U.S. combat forces, wherever they are deployed in the world, could be unacceptably endangered through successful exploitation of this data.”6

When Wolf Blitzer came out with his article in the Washington Post describing some of the intelligence Pollard had passed to Israel, it prompted Weinberger, on the eve of the sentencing, to submit another memorandum to the court. In this second memorandum, unclassified, he strongly aired his personal and professional feelings.

It is difficult for me, even in the so-called year of the spy, to conceive of a greater harm to national security than that caused by the defendant in view of the breadth, the critical importance to the United States, and the high sensitivity of the information he sold to Israel. That information was intentionally reserved by the United States for its own use, because to disclose it, to anyone or any nation, would cause the greatest harm to our national security. Our decisions to withhold and preserve certain intelligence information, and the sources and methods of its acquisition, either in total or in part, are taken with great care, as part of a plan for national defense and foreign policy which has been consistently applied throughout many administrations. The defendant took it upon himself unilaterally to reverse those policies and national assets, which have taken many years, great effort, and enormous national resources to secure.7

Pollard had betrayed the public trust and the security of the United States for money. Weinberger went on to say that any citizen, particularly a trusted government official, who sells secrets to any foreign nation, be it friendly or hostile, should be punished not as a common criminal but in a way that reflects “the perfidy of the individual’s actions, the magnitude of the treason committed, and the needs of national security.”

The defendant had both likened himself to an Israeli pilot shot down behind enemy lines and expressed the hope of emigrating to Israel. “Whatever else his analogy suggests,” the defense secretary commented, “it clearly indicates that his loyalty to Israel transcends his loyalty to the United States.”8 Weinberger mentioned the Washington Post article without confirming or denying the information Pollard had released to Blitzer: “I have no way of knowing whether he provided additional information not published in that article, but I believe that there can be no doubt that he can, and will, continue to disclose U.S. secrets without regard to the impact it may have on U.S. national defense or foreign policy. Only a period of incarceration commensurate with the enduring quality of the national defense information he can yet impart will provide a measure of protection against further damage to the national security.”9

In the end, much to Blitzer’s relief, an expert analysis of the content of his article revealed that the context was broad and the information not classified. During the sentencing phase, it appeared that Judge Robinson decided to ignore the article and concentrate strictly on the revelations offered by Weinberger in his first, classified memorandum.

Having never read the uncensored copy of that memorandum, and knowing I will never be allowed to, I asked Rich Haver to comment in a general way on the severity of Pollard’s crimes. When someone like Pollard takes “the keys to the kingdom,” Haver told me, the harm is incalculable and possibly unstoppable. Such information gives a foreign nation not only a step-by-step blueprint of America’s intelligence-collection capabilities, sources, and methods, but also the ability to analyze those capabilities and to identify vulnerabilities. It tells a country, in essence, how to test American security systems and avoid detection. When the United States loses its ability to protect its citizens, they stand to lose their freedom.

At one point, Haver said, Pollard was out of the office sick and it disrupted his daily routine of gathering secrets. When the Israelis found out that their gofer had not retrieved messages during that time, they were extremely upset with him. Government officials who participated in the damage assessment suspect that Israel was testing some of the SCI manuals Pollard had turned over to them, conducting clandestine operations to gauge American vulnerabilities. According to Haver, in a larger attempt to override U.S. intelligence-gathering capabilities, Israel wanted to see if the United States was able to pick up communications on its secret training operations.

Pollard also damaged U.S. relations with Middle Eastern countries. At a time when the United States was trying to establish a working relationship with Tunisia, he provided the Israelis with highly classified satellite photographs indicating the location of the PLO headquarters there. In October 1985 a U.S. delegation was meeting with the Tunisians in Tunis to lay the groundwork for establishing a relationship when the Israelis led a bombing mission on the PLO headquarters. Infuriated, the Tunisians accused the United States of giving away the location to Israel and knowing about the attack. After all, Israel was the United States’ closest ally in the Middle East, they reasoned. Nothing the delegates said could convince their hosts otherwise, and the Tunisians promptly asked them to pack their bags and leave.

The U.S. government didn’t discover the truth about the satellite photographs until after Pollard was arrested. Pollard’s hubris was evident in his taking full credit for the raid. The incident wiped out several years of negotiations with Tunisia and severely hampered U.S. attempts to gain the trust of other Middle Eastern countries, of critical importance in bolstering American foreign policy.10

In its memorandum in aid of sentencing, the government emphasized that “the widely published reports of defendant’s espionage activities on behalf of Israel have led to speculation within other countries in the Middle East, with which the United States also has enjoyed friendly relations, that defendant’s unauthorized disclosures to Israel may have adversely affected the national security of these other Middle Eastern countries.” Moreover, allies of the United States “have expressed serious concern that a government employee with such far-ranging access to sensitive information has breached his . . . duty to protect that information.” In arguing for a stiff sentence, the government made the point that “if a less severe sentence were ruled out because the foreign nation involved is a U.S. ally, a potentially damaging signal would . . . be communicated to . . . foreign countries contemplating espionage activities in the United States.”11

In addition to damaging relations with the Middle East, Pollard’s activities could have weakened the hand of the United States in its dealings with the Soviet Union. In his book The Samson Option, Seymour Hersh alleges that Israel passed some of Pollard’s top secret information to the Soviet Union in exchange for Russian Jewish prisoners. Although this has never been proven, it is a fact that a significant portion of the thousands of documents Pollard took from the DIA had nothing to do with the Middle East. According to Stephen Green in an article that appeared in the May 1989 issue of the Christian Science Monitor, many such documents contained details about both U.S. and Soviet communications and military capabilities, suggesting that they could have been of use to only one country, the Soviet Union. “This concern was heightened,” Green writes, “when, during the Pollard investigation, a Soviet defector in U.S. hands revealed in addition to the two Israeli spies serving prison terms in Israel for spying for the Soviets, Shabtai Kalmanovitch and Marcus Klingberg, there was a third person Israel had not yet caught. . . . This person was well placed in the [Israeli] Defense Ministry and still active.”12

Colonel Shimon Levinson was another convicted Israeli spy. During an assignment in Bangkok in 1983, Levinson offered his services to the KGB. Two years later, during Pollard’s ascent, the colonel was appointed security chief for the Israeli prime minister’s office. (Rafael Eitan served as a special intelligence adviser in this same office.) Israel later accused Levinson of passing highly classified nuclear and military intelligence to the KGB, and he was arrested in May 1991.13 Was Levinson the unknown third spy? And if so, did the Soviet Union receive through him at least some of the information that Pollard delivered into the hands of the Israelis?

The American public will probably never know the true extent of the devastation Pollard visited on the national security of the United States. The lion’s share of the information he sold was coded TS/SCI, and that sort of material is rarely declassified. One thing is certain: in terms of volume of classified material that Pollard removed, the U.S. agency hardest hit was the DIA. The loss was so devastating that it prompted officials there to strengthen their counterintelligence awareness program. In 1989, when I served as division chief of counterintelligence investigations at NIS headquarters, the DIA approached me about helping them coordinate interviews for their training film on this subject for their employees. The result, Jonathan Pollard: A Portrayal, addressed the damage the spy had done to national security and illustrated the ease with which he managed to commit his crimes. Eventually, the film would be shown to every DIA employee around the world and in many navy commands, making the name Pollard synonymous with treason.