Enter the Softmax

Check out the activation functions in our neural network. So far, we took it for granted that both of those functions are sigmoids. However, most neural networks replace the last sigmoid, the one right before the output layer, with another function called the softmax.

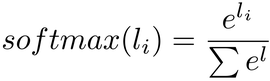

Let me show you what the softmax looks like, and then we’ll see why it’s useful. Like the sigmoid, the softmax takes an array of numbers, that in this case are called the logits, and returns an array with the same size as the input. Here is the formula of the softmax, in case you want to understand the math behind it:

You can read this formula as: take the exponential of each logit and divide it by the summed exponentials of all the logits.

You don’t need to grok the formula of the softmax, as long as you understand what happens when we use the softmax instead of the sigmoid. Think about the output of the sigmoid in our MNIST classifier, back in Decoding the Classifier’s Answers. You might remember that for each image in the input, the sigmoid gives us ten numbers between 0 and 1. Those numbers tell us how confident the perceptron is about each classification. For example, if the fourth number is 0.9, that means “this image is probably a 3.” If it’s close to 0.1, that means “this image is unlikely to be a 3.” Among those ten results, we pick the one with the highest confidence.

Like the sigmoid, the softmax returns an array where each element is between 0 and 1. However, the softmax has an additional property: the sum of its outputs is always 1. In mathspeak you would say that the softmax normalizes that sum to a value of 1.

That’s a nice property, because if the numbers add up to 1, then we can interpret them as probabilities. To give you a concrete example, imagine that we’re running a three-class classifier, and the weighted sum after the hidden layer returns these logits:

logit 1 | logit 2 | logit 3 |

|---|---|---|

1.6 | 3.1 | 0.5 |

Judging from these numbers, it seems likely that the item that we’re classifying belongs to the second class—but it’s hard to gauge how likely. Now see what happens if we pass the logits through a softmax:

softmax 1 | softmax 2 | softmax 3 |

|---|---|---|

0.17198205 | 0.77077009 | 0.05724785 |

What’s the chance that the item belongs to the second class? Take a glance at these numbers, and you’ll know that the answer is 77%. The first class is way less likely, hovering around 17%, while the third is a measly 6%. Add them together, and you get the expected 100%. Thanks to the softmax, we converted vague numbers to human-friendly probabilities. That’s a good reason to use softmax as the last activation function in our neural network.