DINOSAURS are extremely popular, and not a week goes by without some new dinosaur discovery appearing in the newspapers, magazines, the Internet, or on radio and television. Popular books on dinosaurs, for children and adults, are legion. Life-size sculptures of dinosaurs adorn museums and parks, and toy dinosaurs are a staple item of department and toy stores. Paintings and drawings of dinosaurs permeate dinosaur books and museums, and dinosaurs have been the subject of myriad movies, cartoons, and television shows. The word “dinosaur” is part of the English language, and it would be difficult to find an American who hasn’t used this word at least once. The word “dinosaur” has been transliterated or translated into almost all the world’s languages. For example, in Chinese it is pronounced “kong-long” and literally means “monstrous dragon.”

The preceding sixteen chapters of this book have been concerned with the paleontological understanding of dinosaurs. In this chapter, I take a paleontological perspective on some aspects of the public presentation and perception of dinosaurs.

As stated in

chapter 1 and elaborated on in

chapter 4, a dinosaur was a reptile with an upright limb posture. Dinosaurs lived during the Late Triassic through the Cretaceous, between 225 and 230 to 66 million years ago, and were the ancestors of birds. Large size was not a characteristic of all dinosaurs, but this group of animals did include the largest land animals.

Some of these defining features of dinosaurs, the

denotation of the word

dinosaur, are familiar to most people and appear as the primary definition of dinosaur in dictionaries. But, a second definition of dinosaur also appears in them, using “dinosaur” as a word to refer to something unwieldy or out-of-date. This use of the word “dinosaur” may be thought of as its

connotation: a negative image of something no longer useful and so deservedly extinct.

No doubt heavy emphasis on the bulkiness of many dinosaurs and their extinction created this connotation of the word “dinosaur.” But, as we have seen in this book, it is hardly deserved. Many dinosaurs were fast and agile animals. Dinosaurs existed for about 160 million years, during most of which time they dominated the earth. Their descendants, the birds, are among the most diverse and successful groups of living animals.

So, although dinosaurs are extinct, they should stand as paragons of evolutionary success. Instead, they are often thought of as dim-witted, unwieldy failures, which is an undeserved reputation.

New discoveries of dinosaurs frequently appear in the news media before they are published in scientific journals and books. There are two obvious reasons for this. First, paleontologists, like most people, have a natural desire to receive public recognition for their discoveries. Second, publicity about paleontological discoveries is one way to educate the general public about dinosaurs. Funding agencies and scientific institutions, such as museums and universities, seek publicity for dinosaur discoveries made by their paleontologists, both to educate the public and to enhance their institutions’ reputations.

In an ideal world, news reports about dinosaur discoveries should serve the public’s desire for up-to-date, factual information on the latest developments in dinosaur research. But there is an unfortunate downside to media coverage of dinosaurs. This, in part, results from journalistic biases and mistakes. Most reporters are not scientists, and some unintentionally introduce factual errors into stories about dinosaurs. Also, because every news story has to have an “angle”—an aspect that makes it appealing to the journalists and, they hope, the public—many stories about dinosaurs focus on the sensational and speculative. News stories, whether print, audio, or video, are necessarily short, so they usually cannot present all the evidence that supports their conclusions. Much of the media coverage of dinosaurs is tantalizing but incomplete and sometimes contains errors and highly biased and speculative conclusions for which there may be little factual basis.

A second problem with media coverage rests with the paleontologists themselves. The desire for recognition, or the pressures imposed by funding agencies and institutions for results, have sometimes led to sensational news reports about dinosaurs. Subsequent research, however, has revealed that these reports lacked substance and so misinformed the public. Fortunately, these occurrences are few and far between, and most dinosaur discoveries that appear in the press, if accurately presented by reporters, convey new and significant information.

News reports about dinosaurs will always be with us, so how can you distinguish the good from the bad? Certainly, the more you know about dinosaurs, the better equipped you will be to make such judgments. But, perhaps the best thing to do is be critical of the story, asking yourself the following questions: What, if any, biases does the story portray? How many facts—actual information on the fossils, their context, and the lines of reasoning—does the story contain? Also, if the news story draws conclusions, are alternative possibilities and evidence discussed? Few news stories about dinosaurs may stand up to such critical scrutiny, but by asking yourself these questions you may be able to separate those few stories that mislead and misinform from the wealth of new and useful information.

A sizable library is needed to house all the dinosaur books available in today’s bookstores. Technical scientific books on dinosaurs are numerous and can fill a large bookshelf. Nontechnical books fall into three categories: children’s books (and comics), popular factual books on dinosaurs, and dinosaur fiction. This is not the place to recommend or criticize any specific book, but a few comments on what to look for in dinosaur books, and how they influence the public perception of dinosaurs, are in order.

Many misconceptions about dinosaurs are perpetuated in today’s books. A wide range of children’s books on dinosaurs identify the sail-backed reptile Dimetrodon as a dinosaur, which it most certainly was not. Comic books often portray humans coexisting with dinosaurs. But perhaps most pervasive in popular books is the image of dinosaurs as animals that did little more than tear each other apart or search for something else, often a human, to eat. Indeed, such dinosaur carnage is so frequent a theme that most people don’t realize that the average day of a dinosaur, like that of most living animals, was probably rather peaceful. Dinosaurs slept, reproduced, played, and rested—they were not always locked in mortal combat.

When buying dinosaur books for children, the goal should be to avoid such misinformation. However, those of us seeking action and adventure in our reading may not care about accuracy. Indeed, a certain lack of accuracy pervades one of the most influential, though now little read, works of dinosaur fiction. This book, Arthur Conan Doyle’s

The Lost World (1912), is based on the premise that dinosaurs are still living on a high plateau in the Amazon jungle (

box 17.1). Although the book contains many misconceptions about dinosaurs, it still makes exciting reading, and its premise has been the basis for many other works of dinosaur fiction and dinosaur movies.

Although it is difficult to be too critical of the information about dinosaurs presented in books of fiction, readers should demand accuracy of popular books that purport to present dinosaur science to the public. Again, as in the case of news stories on dinosaurs, your ability to evaluate such books increases with your knowledge of dinosaurs. A particularly good measure is the accuracy of the dinosaur restorations and information presented in the book. Do they reflect current scientific thinking about dinosaurs, or are they based on old and outmoded notions? Also, when the book presents topics hotly debated by paleontologists, such as dinosaur metabolism or extinction, does it discuss alternative evidence and ideas? Hopefully, this textbook meets these criteria and provides you with a standard by which to evaluate other dinosaur books.

This section would not be complete without some mention of the technical scientific literature on dinosaurs. Articles on dinosaurs in scientific journals and scientific books about dinosaurs are available in any university library, and many are also easily accessed online. These articles and books represent the ultimate written authority on what paleontologists know and think about dinosaurs. But, they need to be read critically, because the scientific study of dinosaurs is continually growing and changing through new discoveries and interpretations as well as spirited scientific debate.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930) is best known as the creator of Sherlock Holmes, the most famous and skilled detective of all time. However, Doyle’s novel The Lost World (1912) has influenced the genre of dinosaur movies since the film version of the book appeared in 1925.

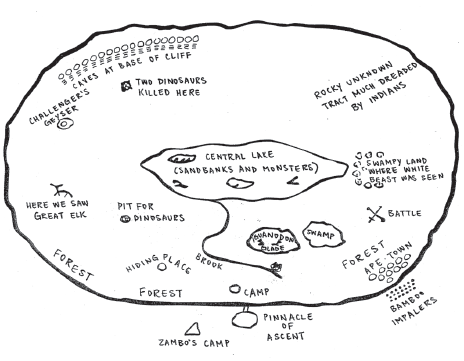

The Lost World is mostly the story of an expedition, led by a British scientist, Professor George E. Challenger, to a high plateau in the upper reaches of the Amazon River inhabited by dinosaurs, mastodons, and a belligerent race of ape men. In the novel, a map of the high plateau shows the expedition’s campsites, the village where the ape men live, locations of dinosaur sightings, and other features (

box figure 17.1). It might seem that such a map was a totally imaginative exercise of Doyle’s, but it actually had some basis in fact.

BOX FIGURE 17.1

The map of the lost world in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World is remarkably similar to a map of the Weald in England.

Doyle was an avid rock and fossil collector well acquainted with discoveries made in Great Britain. Many of Britain’s Early Cretaceous dinosaurs, notably Iguanodon, and its most infamous fossil human, the Piltdown man, a scientific hoax discovered in 1912 and debunked in the 1950s, come from a region in southwestern England called the Weald. A map of this area shows several points of resemblance to Doyle’s map of the lost world.

Thus, the “central lake” corresponds to the Hastings Sands, rocks that contain fossils of Iguanodon and were thought in Doyle’s day to represent Early Cretaceous lakes and swamps (now they are considered to be mainly river and beach deposits). Indeed, an Iguanodon glade and swamp are present in the lost world. The site of the battle with the ape men in the lost world nearly matches that of the town of Battle in the Weald. Similarly, Lavant Caves in the Weald is mirrored by the “hiding place” of the lost world, the “brook” mimics the Ouse River, and “Challenger’s geyser” corresponds to Waggoner’s Wells. Finally, Beachy Head in the Weald is a promontory on the British coast that corresponds to the “pinnacle of ascent” of the lost world.

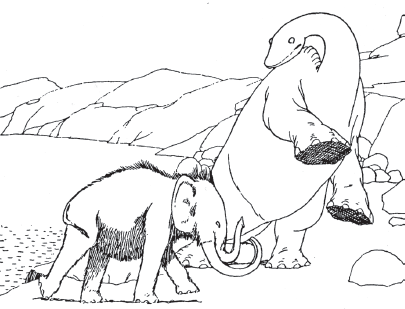

Clearly, Doyle borrowed heavily from fact to create the fictional lost world. But, a tremendous amount of nonfact appears in The Lost World as well. Ape men and mastodons coexist with dinosaurs, and dinosaurs of different geologic time periods live together on the high plateau. Also, long outmoded prejudices about dinosaurs fill the book. Witness, for example, the conclusions of Professor Challenger and his colleague Sumerlee on the intelligence of dinosaurs:

Both were agreed that the monsters were practically brainless, that there was no room for reason in their tiny cranial cavities, and that if they had disappeared from the rest of the world, it was assuredly on account of their own stupidity, which made it impossible for them to adapt themselves to changing conditions.

Doyle’s book, though in part based in fact, helped to create and perpetuate some common misconceptions about dinosaurs and the dinosaurian world.

Artists began to create dinosaur art, such as sculptures and paintings, not long after Richard Owen coined the word “dinosaur” in 1842. In 1854,

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins built life-size models of

Iguanodon,

Megalosaurus, and

Hylaeosaurus (a nodosaurid ankylosaur) that still stand in London’s Crystal Palace Park (see

figure 11.3). These sculptures, and indeed all dinosaur art, reflect paleontological ideas about the biology and behavior of dinosaurs current when the artwork was created. Hawkins’s dinosaurs are the massive, toad- and lizard-like giants that Richard Owen and his colleagues conceived from only a fragmentary knowledge of dinosaur anatomy. For example, Hawkins’s

Iguanodon has the spike on its nose, as believed to be the correct placement by Gideon Mantell in the 1820s, not on the thumb, as was later revealed by the discoveries at Bernissart.

In

chapter 11, we saw that new discoveries have radically changed ideas about dinosaur biology and behavior. Dinosaur art has changed as well. By the beginning of the twentieth century, complete skeletons of dinosaurs were known that provided a far better basis for dinosaur sculptures and paintings than was available to Hawkins.

The most famous dinosaur artist then, and perhaps the most influential dinosaur artist of all time, was

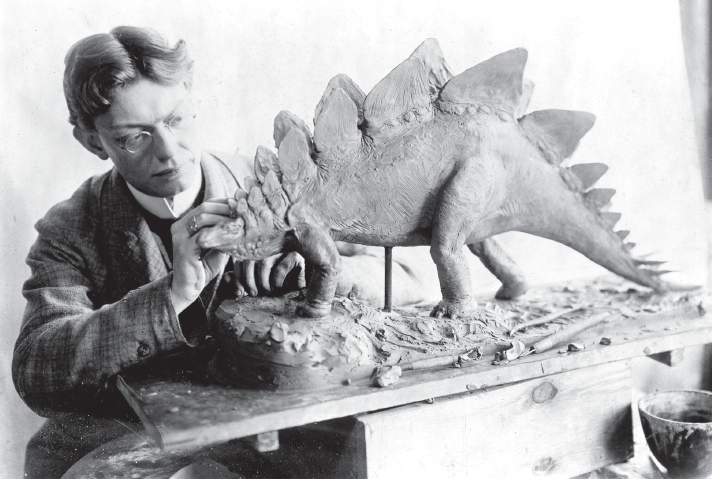

Charles R. Knight (1874–1953) (

figure 17.1). Knight painted and sculpted many dinosaurs, mostly with the advice of paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn (1857–1935) of the American Museum of Natural History. Although most people don’t realize it, the images of dinosaurs created by Charles R. Knight permeated dinosaur art for more than half a century and shaped the work of many dinosaur artists. His restorations are some of the most familiar, and most copied, images of dinosaurs.

FIGURE 17.1

Charles R. Knight was the most influential dinosaur artist. (Courtesy Department of Library Services, American Museum of Natural History, New York [negative no. 327667])

Knight’s dinosaurs reflected accurate anatomical information based on complete skeletons and ideas about dinosaur biology and behavior current in the early years of the twentieth century. His dinosaurs are very reptilian and often heavy and ponderous, dragging their tails. Sauropods are presented in aquatic settings. Yet, some of Knight’s artwork was prescient of future ideas about dinosaurs, such as his painting of two agile fighting theropods of the genus

Dryptosaurus (

figure 17.2). During his life, Knight made some 800 drawings, 150 oil paintings, and numerous sculptures of extinct animals, many of dinosaurs. They are an incredible legacy that has influenced the public perception of dinosaurs more than the work of any other artist.

Today, many talented artists sculpt and paint dinosaurs. Their work reflects the latest ideas about dinosaurs, particularly their bird-like appearance, speed, and agility.

FIGURE 17.2

One of Knight’s early dinosaur paintings, this view of two theropods, Dryptosaurus, fighting, from 1897, presages later ideas about agile theropods. (Courtesy Department of Library Services, American Museum of Natural History, New York [negative no. 335199])

Viewing dinosaur art is much like reading books about dinosaurs. The same criteria of accuracy should be applied to your judgment of dinosaur art, tempered, of course, by your own sense of aesthetics.

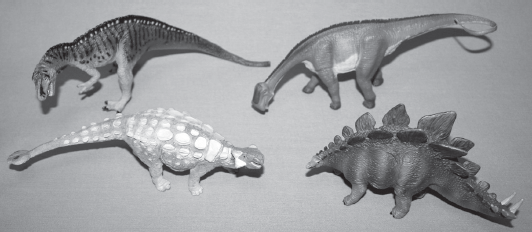

Dinosaur toys, typically small, plastic scale models, are a form of dinosaur sculpture. They should be judged by their anatomical accuracy with respect to complete skeletons of dinosaurs. Unfortunately, most toy dinosaurs fall short of the mark. They are typically very bulky, garishly colored, and anatomically inaccurate (note especially the plates on many toy Stegosaurus). Many sets of dinosaur toys are also full of nondinosaurs—Dimetrodon, pterosaurs, mastodons, mammoths, “cave men,” and, in some sets, mythical beasts unknown to science.

The most accurate dinosaur toys have been marketed by some of the world’s great natural history museums (

figure 17.3). These toys, and other toys that lack the flaws mentioned earlier, provide reasonably accurate scale models of dinosaurs consonant with modern paleontological thought.

FIGURE 17.3

These dinosaur toys, endorsed by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, are among the most accurate on the market.

The first character to appear in an animated cartoon was a sauropod dinosaur, Gertie the Dinosaur, created by cartoonist

Winsor McCay (1869–1934) in 1912 (

figure 17.4). Since that time, dinosaurs have been featured in many cartoons, typically coexisting with humans or other animals that did not evolve until long after dinosaur extinction.

Dinosaurs got their start in movies in 1925 when Hollywood produced a silent film version of

The Lost World. The dinosaurs in this movie were straight out of the paintings of Charles R. Knight (

figure 17.5).

Willis Harold O’Brien (1886–1962), who pioneered the techniques of stop-action photography, joined forces with sculptor

Marcel Delgado (1901–1976) to produce the scale models of the dinosaurs used in the movie. The life-like quality of these models and their movement has seldom been surpassed by later dinosaur movies. Few readers of this book have likely seen the 1925 version of

The Lost World, but most know the quality of the O’Brien–Delgado dinosaurs from the classic

King Kong (1933), on which they also collaborated (

figure 17.6).

The Lost World has left an indelible mark on the public perception of dinosaurs for two reasons. First, its premise that dinosaurs are not extinct, but are still living in some remote corner of the globe, has become the basis of many dinosaur movies. And, at the end of the movie (but not in the book), the discoverers of the dinosaurs bring a live sauropod back to London for exhibition. There, the terrified (enraged?) dinosaur escapes, destroying everything it its path until it crashes through a bridge, landing in the Thames for the long swim back to South America. Thus was born the idea, so familiar to dinosaur movie fans, of a prehistoric monster running amok in a modern city.

FIGURE 17.4

This scene from the animated cartoon Gertie the Dinosaur was drawn and photographed by Winsor McCay in 1912. (Courtesy Donald Glut)

FIGURE 17.5

An Allosaurus kills an Apatosaurus in the silent movie The Lost World (1925). (Courtesy Donald Glut)

Another, and more, recent classic dinosaur movie is the blockbuster

Jurassic Park, released in 1993 (

box 17.2). This film set a very high bar for dinosaur restorations, presenting active and anatomically accurate dinosaurs based on a cutting-edge scientific understanding. Almost all dinosaur movies that are not based on the idea of living modern dinosaurs are time-travel movies. We, the viewers, together with the humans in the movie, are transported back in time to the Mesozoic to encounter dinosaurs. A separate subgenre of dinosaur movies is based on the false idea that humans coexisted with dinosaurs and usually features the misadventures of scantily clad cave women and cave men as they are terrorized by dinosaurs.

FIGURE 17.6

King Kong kills a Tyrannosaurus after a pitched battle in the movie classic King Kong (1933). (Courtesy Donald Glut)

All dinosaur movies are based on fantastic premises, so how are we to judge them from a paleontological perspective? Here, our only guide must be the scientific accuracy and quality of motion of the dinosaurs themselves. Many movie dinosaurs are nothing more than iguanas or other lizards, sometimes adorned with spikes or plates (figure 17.7). These movie dinosaurs deserve our scorn as they sprawl across the screen. Other movie dinosaurs, such as

Godzilla, are utterly fantastic creatures whose resemblance to dinosaurs is at best remote (

box 17.3). Many remaining movie dinosaurs are scale models, usually based on the art of Charles R. Knight. However, most recent dinosaur movies and television shows are based on much more modern restorations that were established by

Jurassic Park. Ironically, the dinosaurs that appeared in the first full-length dinosaur movie,

The Lost World, are just about as good from a paleontological perspective as those that have appeared in any movie.

FIGURE 17.7

A caveman (Victor Mature) fights off an attacking dinosaur (actually an enlarged iguana) in the movie One Million B.C. (1940). (Courtesy Donald Glut)

Michael Crichton’s novel Jurassic Park (1990) was the basis for the blockbuster movie of the same name released in 1993. (A sequel, The Lost World, appeared in 1996; a third movie, Jurassic Park III, was shown in 2001; and a fourth installment, Jurassic World, hit the big screen in 2015.) The premise of the book (and the movie) is that by extracting dinosaur blood from a Mesozoic mosquito preserved in amber, scientists isolate dinosaur DNA in order to clone living dinosaurs. The long dead, decomposed DNA is incomplete, but the gaps are filled with pieces from the DNA of living frogs.

The living dinosaurs thus cloned are the attraction of a pricey theme park (the “Jurassic Park”) located on a remote Caribbean island. The plot unravels as a test of the theme park’s accuracy and viability goes terribly awry when a devious computer hacker attempts to steal dinosaur embryos. A dinosaur rampage ensues, and only the luckiest of the good guys (but, alas, not their lawyer!) escape the dinosaur-infested island. The movie thus ends, ripe for a sequel.

Although the theme park is named Jurassic Park, most of its dinosaurs—

Tyrannosaurus, ceratopsians, hadrosaurs—were Cretaceous denizens. They share the park’s limelight with some characteristically Jurassic dinosaurs, such as the brachiosaurs. Cinematic license produces a venom-spitting

Dilophosaurus that startles its victims by raising a broad flap of skin on its neck—wholly conjectural behaviors and structures for which no fossil evidence exists. And the movie features a terrifying troop of

Velociraptor (the “raptors”) too large and too smart to be the real thing.

Despite this and other flights of fancy, Jurassic Park has phenomenal special effects. Compared to any previous movie, it created dinosaurs more life-like and more closely based on the modern scientific understanding of dinosaurs. Paleontologists and others who watched the movie came as close as they ever will to seeing a dinosaur in the flesh. All subsequent dinosaur movies and documentaries have been held to the high standard of dinosaur restorations established by Jurassic Park.

But, what about the basic premise of

Jurassic Park? Can dinosaur DNA be isolated to clone a living, breathing prehistoric monster? Not now, and probably not ever. The vast majority of insects in amber are of Cenozoic age, so they never had a chance to bite a dinosaur (

box figure 17.2). Fragments of dinosaur DNA may be preserved in some fossilized dinosaur bones, but no current technology can begin to replace the missing decomposed pieces of the phenomenally complex DNA molecule to produce a viable structure. Like many other works of science fiction,

Jurassic Park is based on an apparently plausible premise, but one well beyond current possibilities.

BOX FIGURE 17.2

Most fossil insects preserved in amber are of Cenozoic age, so they postdate the dinosaurs. (Courtesy Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, Stuttgart)

Few movie monsters are as famous as Godzilla. Godzilla is a green, nearly 100-meter-tall, bipedal reptile with fiery, radioactive breath and dorsal spikes. Since it first appeared on the silver screen in the movie

Godzilla, King of the Monsters (1954), the Japanese behemoth has been the star of at least 30 films (

box figure 17.3). Memorable images of Godzilla are of it running amok in Tokyo or other locales in the Japanese islands, destroying buildings, vehicles, and the populace with its huge feet; thick, dragging and swinging tail; and enormous flame-throwing mouth.

Godzilla was created under the direction of Japanese special effects expert Eiji Tsuburaya. An actor inside a suit portrayed the monster as it wreaked havoc on miniature models of Tokyo and other locales. A mechanical model also was used in some scenes.

Generations of Japanese and American moviegoers, especially children, have thrilled to the destructive exploits of and, in some of the movies, sympathetic character portrayed by Godzilla. To many, Godzilla is basically a dinosaur with an overlay of a few novel features of the atomic age, including its appetite for radioactivity.

From a paleontologist’s point of view, very little about Godzilla is dinosaurian. True, the overall body shape of Godzilla is basically that of a large theropod. But, everything else is wrong. Godzilla far exceeds the size of any theropod, is much too massively built, has human-like arms and hands, breathes fire, and has spikes on its back like a stegosaur. These are not exaggerations of theropod features, but instead spot Godzilla as a horrific monster not closely related in any way to the theropods despite the filmmaker’s premise that Godzilla, hibernating since the Mesozoic, was awakened by American atomic tests at Bikini Atoll during the 1950s.

Nevertheless, don’t expect this exposé of Godzilla’s nondinosaurian background to curtail its cinematic career and dim its stardom. Like many movie personalities with unsavory private lives and questionable backgrounds, Godzilla has an onscreen appeal that will transcend its doubtful paternity. The most recent Godzilla movie featured the destruction of much of San Francisco. We can no doubt expect more Godzilla movies and the continued popularity of this fantastic monster!

BOX FIGURE 17.3

Movie poster for Godzilla, King of the Monsters (1954).

The past two decades have witnessed an explosion of information in cyberspace available on the worldwide web. If you do a search for the subject “dinosaur,” at least 80 million(!) webpages can be found. They range from the authoritative web sites of the great natural history museums to commercial sites selling dinosaur T-shirts. How can you cut through this morass of information to find accurate and up-to-date information about dinosaurs?

The easiest route is to visit the website of any natural history museum. The really large museums with extensive dinosaur exhibits are your best source. In North America, they include the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. (

http://naturalhistory.si.edu), the American Museum of Natural History in New York (

www.amnh.org), and the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago (

www.fieldmuseum.org). In Great Britain, the Natural History Museum in London (

www.nhm.ac.uk) has information about its dinosaurs on its web page. These, and many other museum web pages, provide varied information about dinosaurs; some even contain virtual tours of the museums’ dinosaur exhibits.

However, an even easier way to reach much (or all) of the dinosaur information on the web is to locate one of the many sites that index the sites on dinosaurs. One of the best of these was put together by the University of California Museum of Paleontology in Berkeley (

www.ucmp.berkeley.edu). This site provides links to other museum sites and offers a wealth of information, including topics such as dinosaur extinction and metabolism.

Table 17.1 lists some informative dinosaur websites.

This review of the public persona of dinosaurs has not been comprehensive. Dinosaurs also appear as jewelry, on postage stamps, as breakfast cereal, and on corporate logos, among other things. The public’s view of dinosaurs, however, is often misinformed. Common misconceptions about dinosaurs include the idea that humans coexisted with dinosaurs, the misidentification of a host of nondinosaurs as dinosaurs, the image of dinosaurs as beefy, ponderous reptiles, and the vision of a dinosaur as a terrifying, bloodthirsty brute bent only on savagery and carnage.

Clearly there is a gap between scientific knowledge about dinosaurs and public perception. Much of the public’s perception of dinosaurs is rooted in outmoded ideas about dinosaurs. Sensationalism and a thirst for action and adventure also pervade the public perception of dinosaurs.

But, the gap is narrowing. Paleontologists know that dinosaurs are fascinating and exciting animals that can stir public interest without being embellished by unfounded ideas. Our new and expanded knowledge of dinosaurs, much of it accumulated during the past 40 years, is being communicated in new books, art, toys, and cinema. As public interest in dinosaurs continues to grow, we can look forward to even more paleontological interest and information on these fascinating animals.

TABLE 17.1 Some Informative Dinosaur Websites

Extensive illustrated catalog of dinosaurs, A to Z

The famous Yale murals by Rudolph Zallinger; dated, but classic

The Zoom Dinosaurs® e-book

The Dino Database site has plenty of data.

The Smithsonian’s site dispels misconceptions and features its dinosaur exhibits.

Dr. Ken Hooper Virtual Natural History Museum of the Ottawa-Carleton Geoscience Centre

An online encyclopedia of dinosaur information provided by Encyclopedia Britannica

National Geographic’s site features all prehistoric animals, including dinosaurs.

Perhaps the most informative dinosaur website of all time

The Discovery Channel’s site focuses on current dinosaur discoveries.

Up-to-date scientific reports on dinosaur science provided by the BBC

1. Dinosaurs are extremely popular and appear in the news media, books, sculptures, paintings, toys, cartoons, television shows, movies, and other items available to the general public.

2. The word “dinosaur” refers to a type of extinct reptile with an upright limb posture but also is used to refer to anything that is unwieldy or obsolete. This latter use of the word is based on the generally large size and extinction of dinosaurs, but this connotation of dinosaurs contradicts their success.

3. News reports about new dinosaur discoveries sometimes are inaccurate and misleading. Such reports need to be viewed critically.

4. Popular dinosaur books frequently perpetuate old, outmoded ideas about dinosaurs and also perpetuate errors, such as the idea that humans coexisted with dinosaurs.

5. Dinosaur sculptures and paintings have changed as scientific ideas about dinosaur biology and behavior have changed.

6. Charles R. Knight’s paintings and sculptures of dinosaurs have influenced images of dinosaurs more than those of any other artist.

7. Many dinosaur toys are inaccurate scale models of dinosaurs.

8. The first animated cartoon character was a dinosaur (1912).

9. The first full-length movie that featured dinosaurs was the 1925 Hollywood silent film version of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World.

10. Most dinosaur movies are based on either the idea of living, twentieth-century dinosaurs or time travel to the Mesozoic.

11. Many dinosaur movies, like most of the public presentation of dinosaurs, perpetuate outmoded or incorrect ideas about dinosaurs.

12. The gap between dinosaur science and the public perception of dinosaurs is being narrowed by new discoveries and the public’s increasing desire to know more about dinosaurs.

connotation

Marcel Delgado

denotation

dinosaur (two meanings)

dinosaur toys

Arthur Conan Doyle

Godzilla

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

Jurassic Park

King Kong

Charles R. Knight

The Lost World

Winsor McCay

misconceptions about dinosaurs

Willis Harold O’Brien

Weald

1. What are the two meanings of the word “dinosaur”? Are they accurate definitions?

2. Why do some news reports present inaccurate information about dinosaurs?

3. What questions should you direct at news reports about dinosaur discoveries to evaluate their accuracy?

4. What misconceptions about dinosaurs are perpetuated by some books, art, and movies?

5. How have paleontological ideas about dinosaurs influenced dinosaur art?

6. What are the subgenres of dinosaur movies?

7. What influence did The Lost World have on subsequent dinosaur movies?

8. What influence did Jurassic Park have on subsequent dinosaur movies?

Crichton, M. 1990. Jurassic Park. New York: Ballantine. (The science fiction book upon which the movie of the same name is based)

Christiansen, P. 2000. Godzilla from a zoological perspective. Mathematical Geology 32:231–245. (Mathematical calculations demonstrate the biological impossibility of Godzilla)

Czerkas, S. 2006. Cine-saurus: The History of Dinosaurs in the Movies. Blanding, Utah: Dinosaur Museum. (A complete history of dinosaur representations in film with many movie stills and posters)

Czerkas, S. M., and E. D. Olson, eds. 1987. Dinosaurs Past and Present. 2 vols. Los Angeles: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and University of Washington Press. (Contains pictures of dinosaur artwork featured in an exhibition organized by the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 12 articles about dinosaur art, and new ideas about dinosaurs)

Doyle, A. C. 1912. The Lost World. London: Hodder & Stoughton. (Originally serialized in Strand Magazine; the story of Professor Challenger’s expedition to a high plateau in Amazonia populated by dinosaurs)

Glut, D. F. 1980. The Dinosaur Scrapbook. Secaucas, N. J.: Citadel Press. (The subtitle of this book is The Dinosaur in Amusement Parks, Comic Books, Fiction, History, Magazines, Movies, Museums, Television)

Milner, R. 2012. Charles R. Knight: The Artist Who Saw Through Time. New York: Abrams. (Complete biography of Charles R. Knight and a review of his artwork)

Padian, K. 1988. New discoveries about dinosaurs: Separating the facts from the news. Journal of Geological Education 36:215–220. (Discusses, with examples, how to distinguish accurate from inaccurate news reports about dinosaur discoveries)

White, S., ed. 2012. Dinosaur Art: The World’s Greatest Paleoart. London: Titan Books. (Ten top paleoartists discuss their methods and style and present examples of their work)