CHAPTER SIX

In the Air

As songwriting, what’s different about “Like a Rolling Stone” is all in its first four words. There may not be another pop song or a folk song that begins with “Once upon a time . . . ”—that in a stroke takes the listener into a fairy tale, off the radio you’re listening to in your car or on the record player in your house, suddenly demanding that all the paltry incidents in the song and all the impoverished incidents in your own life that the song reveals as you listen now be understood as a part of a myth: part of a story far greater than the person singing or the person listening, a story that was present before they were and that will remain when they’re gone. But the entry into the realm of fairy tale, of dragons and sorcerers, knights and maidens, of princes traveling the kingdom disguised as peasants and girls banished from their homes roaming the land disguised as boys, would mean nothing if the singer’s feet were on the ground.

There is that stick coming down hard on the drum and the foot hitting the kick drum at the same time, this particular rifle going off not in the third act but as the curtain goes up. “The first time I heard Bob Dylan,” Bruce Springsteen said in 1989, inducting Dylan into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, “I was in the car with my mother listening to WMCA, and on came that snare shot that sounded like somebody’d kicked open the door to your mind.” Many other recordings have opened with the same formal device, a single drum beat—“From a Buick 6,” on

Highway 61 Revisited, the album “Like a Rolling Stone” leads off, is one—but on no other record does the sound, or the act, so call attention to itself, as an absolute announcement that something new has begun.

8Then for an expanding instant there is nothing. The first sound is so stark and surprising, every time you hear it, that the empty split-second that follows calls up the image of a house tumbling over a cliff; it calls up a void. Even before “Once upon a time,” it’s the first suggestion of what Dylan meant when, on that night in Montreal when he was plainly too tired to bait an interviewer so uninterested in his assignment he hadn’t even bothered to learn how to pronounce his subject’s name, he cared enough about “Like a Rolling Stone” to seriously insist that no one had written songs before—that no one had ever tried to make as much of a song, to altogether open the territory it might claim, to make a song a story, and a sound, but also the Oklahoma Land Rush.

That first shot will be repeated throughout the performance, on Dylan’s own electric rhythm guitar, as for every other measure a hard, percussive snap seals a phrase, cuts off one line of the story and challenges the moment to produce another. That first announcement is brought inside the sound, so that it becomes a signpost, reappearing every other step of the way: a mark of how far the story has gone, which is to say a mark of how much ground that can never be recovered has been left behind. The silence, too, is repeated, in breaks in the sound too brief to measure but that in their affective force can seem enormous: the entire ensemble rising up and then stopping at the top of a surge, just after the first “How does it feel” of the final chorus, as if the song itself has to pause to catch its breath for the final chase; Dylan himself, in the time it takes the last word of the song to leave his mouth and his mouth to reach the harmonica on the rack on his chest for the slashing phrase that seals the end of the song as fiercely as the stick on the snare opened it. In these moments of suspension there is a kind of ghost, the phantom of a comforting past, where everything remains the same. In the maelstrom of the performance itself, in each step forward on the fairy-tale road, where when you look forward you see mountains too high to climb and when you look back you see nothing, it is the sense that you could take it all back, that you could retrace your steps, that you could go home, that it’s not too late.

As a sound the record is like a cave. You enter it in the dark; what light there is flickers off the walls in patterns that, as you watch, seem almost in rhythm. You begin to feel that you can tell just what flash will follow from the one before it. But the longer you look, the more you see, and the less fixed anything is. The flickers turn into shadows, and the movement the shadows make can never be anticipated. Suddenly the dark, the light, and the shadows are all speaking to you, each demanding your attention. You can’t look in all directions at once but you feel you must. The room begins to whirl; you try to focus on a single element, to make it repeat itself, to follow it, but you are instantly distracted by something else.

This is what happens in “Like a Rolling Stone.” The sound is so rich the song never plays the same way twice. You can know that, for you, a certain word, a certain partial sound deep within the whole sound, is what you want; you can steel yourself to push everything else in the song away in anticipation of that part of the song you want. It never works. You lie in wait, to ambush the moment; you find that as you do another moment has sneaked up behind you and ambushed you instead. Without a chorus the song would truly be a flood, not the flood of words of “Come una Pietra Scalciata” but a flood that sweeps up everything before it—and yet as the song is actually sung and played, the chorus, formally the most determined, repeating element in the song, is the most unstable element of all.

There are drums, piano, organ, bass guitar, rhythm guitar, lead guitar, tambourine, and a voice. Though one instrument may catch you up, and you may decide to follow it, to attend only to the story it tells—the organ is pursuing the story of a road that forks every time you turn your head, the guitar is offering a fable about a seeker who only moves in circles, the singer is embellishing his fairy tale about the child lost in the forest—every instrument shoots out a line that leads to another instrument, the organ to the guitar, the guitar to the voice, the voice to the drums, until nothing is discrete and each instrument is a passageway. You cannot make anything hold still.

Because the song never plays the same way twice—because whenever you hear the song you are not quite hearing a song you have heard before—it cannot carry nostalgia. Unlike any other Bob Dylan recording that might be included on Golden Protest, the next time you hear “Like a Rolling Stone” is also the first time. That first drum shot is what seals it: when the stick hits the skin, even as a house tumbles forward, the past is jettisoned like a missile dumping its first stage. In that moment there is no past to refer to—especially the past you yourself might mean to bring to the song.

I saw this happen once, as if it were a play. It was about eleven in the morning in Lahaina, on Maui, in 1981, in a place called Longhi’s, a restaurant made of blonde wood and ceiling fans. There were ferns. People were talking quietly; even small children were lolling in the heat. Everything seemed to move very slowly. There was a radio playing tunes from a local FM station, but it was almost impossible to focus on what they were. Then “Like a Rolling Stone” came on, and once again, as in the summer of 1965, sixteen years gone, with “Like a Rolling Stone” supposedly safely filed away in everyone’s memory, the song interrupted what was going on: in this case, nothing. As if a note were being passed from one table to another, people raised their heads from their pineapple and Bloody Mary breakfasts; conversations fell away. People were moving their feet, and looking toward the radio as if it might get up and walk. It was a stunning moment: proof that “Like a Rolling Stone” cannot be used as Muzak. When the song was over, it was like the air had gone out of the room.

In early rock ’n’ roll—in the Drifters’ 1953 “Money Honey,” Elvis Presley’s 1956 “Hound Dog,” Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” and Dion and the Belmonts’ “I Wonder Why,” both from 1958—you can hear the reach for the total sound that hovers in “Like a Rolling Stone.” Sometimes the reach almost is the sound, as with the insensate, nearly a cappella last verse of Little Richard’s 1956 “Ready Teddy,” where he seems less a singer than a medium for some nameless god. Or in the preternaturally fast, perfectly balanced leaps that kick off “Johnny B. Goode” and “I Wonder Why.” In the first it’s six seconds of a guitar answered by a single downbeat combination on the drums, in the second it’s a downpour of doo-wops, bassman Carlo Mastrangelo’s did-did did-it did-didda-did-it s before the leader comes in, for thirteen seconds a field for the other Belmonts to turn backflips into eternity. But “Money Honey” is probably the template. Of all the many first rock ’n’ roll records it is the most unfettered, and it wasn’t just a reach. At least for an instant you can feel the prize in its grasp.

The Drifters came about when in the spring of 1953 lead singer Clyde McPhatter was kicked out of the Dominoes, a hit rhythm and blues vocal group. Ahmet Ertegun of the young Atlantic label put McPhatter together with the four-man Thrasher Wonders and gave them all a new name. With the Dominoes, on angelic performances of “Close the Door,” “When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano,” and “Don’t Leave Me This Way,” McPhatter’s high tenor was the voice of the ineffable, tugging at your sleeve. As a Drifter he was a dynamo unlike anything pop music had seen before, but it was all over by 1954, when McPhatter received his draft notice. When he returned he never really found his music again. He died a forgotten drunk in 1972; he was thirty-nine. But in his one year of greatness he came out of himself. He ran wild with his own songs, with songs by Atlantic’s musical director Jesse Stone—or for that matter Irving Berlin. As you listen now, a new man appears before you when McPhatter sings “Honey Love,” “Such a Night,” or “Let the Boogie Woogie Roll”; a story tells itself. The sly smile in the music communicates the notion that the singer is getting away with the best prank imaginable while the whole world watches, with the whole world asking, “Who was that masked man?” when the record ends, the world then playing the record again and again as if by doing so the world could find out. The man before you is young and beautiful, charming, urbane, utterly cool, yet at any moment a sense of weightlessness, of pure fun, can break out and engulf the entirety of his performance. The man is a trickster. For “White Christmas,” the other Drifters begin respectfully. They finish a verse—and then the Imp of the Perverse arrives, McPhatter singing like Rumpelstiltskin promising to spin straw into gold, leaving the nation dumbfounded with his whirling falsetto, open-mouthed in the face of a reversal of the country’s shared cultural symbolism that in pop music would not be matched until Jimi Hendrix used “The Star-Spangled Banner” to speak to the Founding Fathers.

“Money Honey” is a comic song, but in McPhatter’s performance the humor is all in the bottled-up urgency he gives Jesse Stone’s lyrics, and the humor is real life. “Without love there is nothing,” McPhatter would sing softly in one of his solo hits; the message of “Money Honey” is that without money there’s no love. Still, there’s the thrill of the chase. Part of the delight of “Money Honey” is waiting to hear if the next verse can top the one before it, tell a better story, and from the landlord at the door to the realization that the singer needs a new girlfriend—and the girlfriend a new boyfriend—it always does. But the overriding shock is that as all parts of the music come together, you are present at a creation—the creation or the discovery of rock ’n’ roll. The special energy that only comes when people sense they are putting something new into the world, something that will leave the world not quite as it was, rises up. “Ah-ooooom,” begin tenors Bill Pinkney and Andrew Thrasher, bass Willie Ferbie, and baritone Gerhart Thrasher, low and ominous, and then McPhatter begins the quest that will occupy him for the rest of the song: the quest for his rent. He takes the first verse full of enthusiasm; there’s a stumble on the drums as there will be on every verse, but he leaps over it. The second verse is congenial—he’s trying to get his dearly beloved to open her purse—but on the third verse it’s her words that are coming out of his mouth: We’re through. McPhatter bears down, almost scared, and everything in the music tightens, goes hard and mean. McPhatter shouts for the instrumental break, saxophonist Sam “The Man” Taylor comes in for his solo—and he burns it, rocketing the music out of anything it’s prepared you for, the beat now rushing upstream too fast to track, and then McPhatter screams.

There is nothing like this scream—not in McPhatter’s own music, or in any of the music to follow his, as Elvis Presley and Jackie Wilson and Sam Cooke tried to wrap their voices around their memories of McPhatter’s, as something of his drive and flair filtered down over the years to the countless singers who wouldn’t recognize his name. It’s a scream of surprise—it’s the scream of a man watching a door blow out, a man who’s made it to the other side and is ready now to reach back and pull everyone over. The record ends conventionally, and you wonder: did that happen?

As if from the other side of the earth, you can hear something similar in Robert Johnson. Though the recordings Son House made in 1930 can seem like the summation of all the knowledge amassed by the divines of the School of the Mississippi Delta Blues, in comparison with the recordings Johnson made in 1936 and 1937, when he was in his midtwenties—“Come on in My Kitchen,” “Traveling Riverside Blues,” “Hellhound on My Trail”—most of the masters who preceded him sing and play as men who have accepted the world as they found it. They speak the language of what is known; playing and singing with more force and more delicacy, with lines that are like staircases to ceilings and windows opening onto walls—ceilings and walls that the music opens as if they were doors, and which in the same way the music then closes behind itself—Johnson speaks the language of what isn’t. That isn’t why most of those who came before him lived on long after Johnson’s murder at a Mississippi juke joint in 1938; it does make his music a kind of witness to his death. Inside the figures he made on the guitar and the shadings of his voice there are always possibilities other than those that are stated. At the highest pitch of his music each note that is played implies another that isn’t; each emotion that is expressed hints at what can’t be said. For all of its elegance and craft the music is unstable at its core—each song is at once an attempt to escape from the world as everyone around the singer believes it to be, and a dream that that world is not a prison but a homecoming. Like the Drifters or Dion and the Belmonts, Johnson is momentarily in the air, flying just as one does in a dream, looking down in wonder at where you are, then soaring as if it’s the most natural thing in the world.

Before “Like a Rolling Stone,” Johnson and the Drifters may have come closer to the total sound than anyone else. The desire could be defined even if its realization was impossible—maybe it could be defined because its realization was impossible. The total sound would be all-encompassing, all-consuming. For as long as it lasted that sound would be the world itself—and who knew what would happen when you left that world and returned to the world that, before you heard the sound, seemed complete and finished?

“Like a Rolling Stone” stays in the air. That’s its challenge to itself: to stay up for six full minutes, never looking down. When the song ends it disappears into the air, leaving the earth to all the men and women scurrying through the tunnels and traps of the rest of the country mapped on Highway 61 Revisited, the set of songs it would begin.

As Al Kooper has always told the story, he was just supposed to watch. On June 16, the day after the first, abortive stabs at the song, for which he wasn’t present, he showed up at Columbia’s Studio A as a guest of the producer, Tom Wilson. Born in 1931, dead of a heart attack in 1978, Wilson was a Harvard graduate in economics; in the late 1950s and early 1960s he produced records by John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor. In 1965 he was one of the few black producers at a major label, but after the sessions for “Like a Rolling Stone” he was replaced as Dylan’s producer and cut out of producing Simon and Garfunkel, who would prove to be a far more lucrative act. He went on to MGM/Verve, where he put his name on Freak Out, by Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention, their 1967 “America Drinks and Goes Home” marathon Absolutely Free, and the Velvet Underground’s 1968 White Light/White Heat, which at its most relentless sounded as if it had been recorded in a cardboard box. Wilson had an open mind and open ears. He was a formidable character, but he wasn’t there when Kooper arrived, and Kooper, at twenty-one a longtime veteran of the music business—teenage guitarist for the Royal Teens (after their one hit, “Short Shorts,” number 3 in 1958), songwriter, song-hustler, recording artist (“Sick Manny’s Gym” with Leo De Lyon and the Musclemen in 1960, “Parchman Farm” under his own name in 1963), New York session guitarist—had no intention of kibitzing in the control booth. He sat down with the other musicians Wilson had called for the session, most of them people he already knew: drummer Bobby Gregg, organist Paul Griffin, bassist Joe Macho, Jr., and Bruce Langhorne, guitarist on “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” but this day holding his treasured giant Turkish tambourine. Then Dylan arrived with Michael Bloomfield.

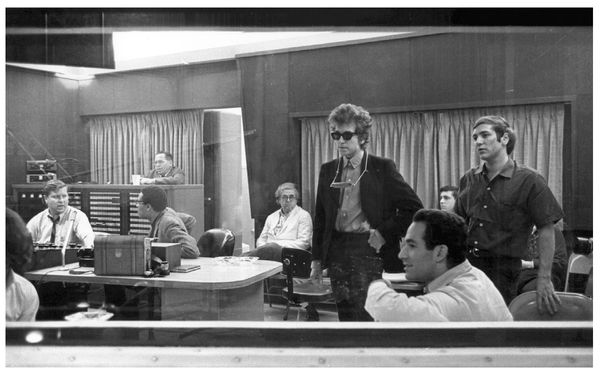

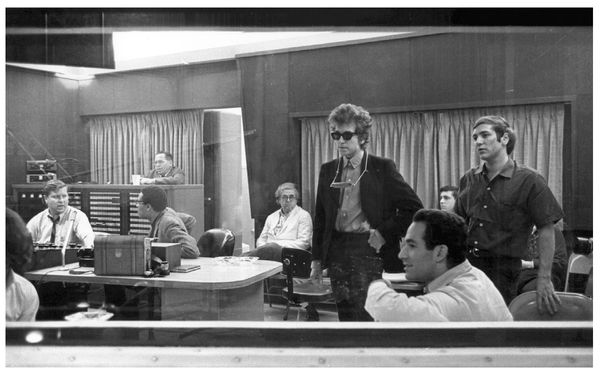

Playback: from left to right, Roy Halee, Pete Duryea (at rear), Tom Wilson, Albert Grossman, Bob Dylan, Vinnie Fusco (at rear), Sandy Speiser (foreground), Danny Kalb

I was playing in a club in Chicago, I guess it was about 1956, or nineteen-sixty. And I was sittin’ there, I was sittin’ in a restaurant, I think it was, probably across the street, or maybe it was even part of the club, I’m not sure—but a guy came down and said that he played guitar. So he had his guitar with him, and he begin to play, I said, “Well, what can you play?” and he played all kinds of things, I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of a man, does Big Bill Broonzy ring a bell? Or, ah, Sonny Boy Williamson, that type of thing? He just played circles, around anything I could play, and I always remembered that.

Anyway, we were back in New York, think it was about 1963 or 1964, and I needed a guitar player on a session I was doin’, and I called up—I didn’t, I even remembered his name—and he came in and recorded an album at that time; he was working in the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. He played with me on the record, and I think we played some other dates. I haven’t seen him too much since then. He played on “Like a Rollin’ Stone.” And he’s here tonight, give him a hand, Michael Bloomfield!

—Bob Dylan, introducing Michael Bloomfield as a guest guitarist on “Like a Rolling Stone,” Warfield Theatre, San Francisco, 15 November 1980

Bloomfield was born in Chicago in 1943; as a barely teenage guitarist he grew up on the radio and in dance bands. He tried to play like Scotty Moore played with Elvis, and mastered Chuck Berry; he followed Cliff Gallup, guitarist for Gene Vincent, and James Burton, whose attack on Dale Hawkins’s 1957 “Susie-Q”—like a mugging—made the record a password. He moved through folk music and country blues, and then into the blues world of his own city. He ran a blues club; when he was eighteen he played piano in a band behind blues singer Big Joe Williams, and then he played with everybody else. “You had to be as good as Otis Rush, you had to be as good as Buddy Guy, as good as Freddie King, whatever instrument you played at the time, you had to be as good as they were,” he once said. “And who wanted to be bad on the South Side? Man, you were exposed all over. Right in that city where you lived, in one night you could hear Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf . . . Big Walter, Little Walter, Junior Wells, Lloyd Jones, just dozens of different blues singers, some famous, some not so famous. They were all part of the blues, and you could work with them if you were good enough.” He found his own sound: “I play sweet blues,” he said in 1968. “I can’t explain it. I want to be singing. I want to be sweet.” “If I could be anything in the world,” a friend said that year, “it would be to be Mike Bloomfield’s notes.”

But as Bloomfield found his sound he couldn’t keep it. In 1967 he left Paul Butterfield, as he had left Dylan after a single show, at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, and formed the enormously publicized Electric Flag, which debuted at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, where the band’s confused blues pastiches and soul tributes were upstaged by Jimi Hendrix, who after singing “Like a Rolling Stone” lit his guitar on fire and prayed to it, the Who, who before smashing their instruments swirled the crowd with eight minutes of their little operetta “A Quick One While He’s Away” (“You’re forgiven!” Pete Townshend shouted at the audience of music business insiders), and, especially, Big Brother and the Holding Company’s version of Willie Mae Thornton’s “Ball and Chain,” the performance that made Janis Joplin an international star. Bloomfield’s band broke up after a single album. He made “Supersession” LPs with Al Kooper and Stephen Stills, late of Buffalo Springfield, all of them trading on glories just past (“Lousy show,” a story from the time had someone saying to one of the three. “Yeah, but we got a couple of albums out of it,” was supposedly the reply); he made solo records, played again with Butterfield and Muddy Waters, but fewer were listening with each release, and there was less and less reason to. He sank into heroin and alcoholism, and pulled himself out. He taught guitar classes; he did soundtrack work for Mitchell Brothers porn movies. In 1981 he was found in his car, dead of an overdose, near his house in San Francisco; he was thirty-seven. Without his presence in “Like a Rolling Stone” his name might be forgotten today. Because of it he is still on the air.

I first met Bob at a Chicago club called “The Bear,” where he was performing. I went down there because I had read the liner notes on one of his albums that described him as a “hot-shot folk guitar player, bluesy, blah-blah-whee, Merle Travis picking, this and that.” The music on his album was really lame, I thought. He couldn’t sing, he couldn’t play.

I went down to the Bear to cut him with my guitar. I wanted to show him how to play music, and when I got there I couldn’t believe it. His personality. He was so nice. I went there with my wife and we just talked. He was the coolest, nicest cat. We talked about Sleepy John Estes and Elvis’ first records and rock and roll . . . He was a nervous, crazy guy.

When Dylan called, Bloomfield said, “I bought a Fender, a really good guitar for the first time in my life, without a case. A Telecaster.”

I went to his house first to hear the tunes. The first thing I heard was “Like a Rolling Stone.” He wanted me to get the concept of it, how to play it. I figured he wanted blues, string bending, because that’s what I do. He said, “Hey, man, I don’t want any of that B. B. King stuff.” So, OK, I really fell apart. What the heck does he want? We messed around with the song. I played the way that he dug and he said it was groovy.

Then we went to the session. Bob told me, “You talk to the musicians, man, I don’t want to tell them anything.” So we get to the session. I didn’t know anything about it. All these studio cats are standing around. I come in like a dumb punk with my guitar over my back, no case, and I’m telling people about this and that, and this is the arrangement, and do this on the bridge. These are like the heaviest studio musicians in New York. They looked at me like I was crazy.

—Michael Bloomfield, “Impressions of Bob Dylan,” Hit Parader, June 1968

Tom Wilson was still missing. “It was already inappropriate that I had gone and sat there with a guitar,” Kooper says. “And then Bloomfield cured me of that. Tom Wilson never saw me out there with a guitar. That was a very lucky part of the day—not being caught by Tom Wilson, and not being stuck having to play guitar next to Mike Bloomfield. He was way over my head. I never heard a white person play like that in my life. Until that moment.”

Wilson returned; Kooper was already back in the control room, out of the game. The players worked toward a sound, but it was off; Wilson moved Paul Griffin from the Hammond organ to the piano, looking for a brighter feeling. “I walked over to Tom Wilson and said, ‘Hey, I got a really good part for this on the organ,’” Kooper says. “He just sort of scoffed at me: ‘Ah, man, you’re not an organ player. You’re a guitar player.’ Then he got called to the phone. And my reasoning said, ‘He didn’t say no’—so I went out there.” “It was a terror tactic,” Kooper says. “There’s a moment, it’s actually recorded, where [Wilson] says, ‘OK, this is take number whateveritis,’ and he goes, ‘Heyyyy—what’re you doin’ out there?’ I just start laughing—and he goes, ‘Awright, awright, here we go, this is take something, “Like a Rolling Stone.”’ So there was that moment when he could have yanked me out of there. I thanked God that he didn’t. It would have been so embarrassing.” So the ensemble was set.

The song they were about to record was not a natural song. As a set of words to sing it was what Dylan always said it was, something pulled out of something else, a story made out of an impulse: “Telling someone something they didn’t know, telling them they were lucky.” One line didn’t necessarily pull the next one after it; sometimes a phrase fell back on the one coming up behind it. Compared only to the songs that on

Highway 61 Revisited would sail in its wake, “Like a Rolling Stone” lacks the balance of the title song, with lines and images whipping back at each other at full speed:

Now the fifth daughter on the twelfth night

Told the first father that things weren’t right

It doesn’t approach the visionary momentum of “Desolation Row,” where a whole new world is built out of the debris of the old and every character in the song, from Einstein to T. S. Eliot, the Blind Commissioner to Cinderella, seems capable of changing into every other. As words on paper, it falls short of “Ballad of a Thin Man” in vehemence. There is nothing careful about the language. Dylan usually had the instincts, or the studied judgment, to avoid the momentary slang and contrived neologisms that would date his songs, box them up and turn them into artifacts. Perhaps because of his scholar’s sense of how folk ballads and early blues came together in the fifty years after the Civil War—sharing countless author-less phrases so alive to their objects (“forty dollars won’t pay my fine,” anybody could say that, and everybody did) that even when the phrases passed out of common usage they could communicate as poetry (“drink up your blood like wine,” not too many could get away with that, and not too many tried)—Dylan had a feel for making phrases of his own that no matter how unlikely

I got forty red white and blue shoestrings

And a thousand telephones that don’t ring

could seem not made but found. His sense of time, or timelessness, only rarely failed him; usually the momentum in his music passed over moments of laziness, when it was easier to plug in words of the day than to find the words that were right. “Just about blew my mind” flies by without damage in “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” and “Blows the mind most bitterly” is carried off by the rhythm in “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).” But street talk can change by the week, and by 1965, “Where it’s at” had lost the charge of real speech it carried in Sam Cooke’s “That’s Where It’s At” just a year before. The words stuck out in “Like a Rolling Stone,” with the expression now less a phrase than a catchphrase, less words you used to say something than an advertising slogan you repeated in spite of yourself. It sounds cheap, broken, as if the writer was in too much of a hurry to get it right, or didn’t care, and the song trips over it, momentarily goes blank as the words are sung. And then the next line is sung.

Something big is about to happen. At the heart of the song, the prince who after years of wandering the land as a vagabond is ready to tell what he has learned; at a fair he gathers twos and threes to hear his promise that he is about to reveal the secret of the kingdom, and soon there is a crowd.

In the studio in New York City, the fanfare opens, with small notes on the piano dancing like fairies over the low, steady pulse from an organ you hear but don’t register. There is a false sense that you can still wait for whatever it is that is about to happen to happen. But when you emerge from the reverie of the song as it begins—in that rising sun of a fanfare there is an invitation to look over your shoulder at a receding, familiar landscape, as if the story that is about to begin is a story you have heard a thousand times (“It’s such an old story,” Bloomfield said)—the train has already left the station. “Once upon a time,” and you are not the child falling asleep as someone reads from Grimm’s Fairy Tales, the violence and gore removed, the illustrations glowing with blonde hair and blue eyes. You’re in the story, about to be cooked, eaten, dismembered, left behind, and as in an early Disney animation the trees in the forest are reaching out their branches like hands and tearing at your clothes. That is what the singer is saying as the music blows all around you, but this isn’t a nightmare, and if it were you wouldn’t want to wake up. This is a great adventure. As if keeping a secret from yourself—the secret of how bad the story sounds and how good it feels—you cover your eyes with your hands and peek through your fingers at the screen.

Bombs are going off everywhere, and every bomb is a word. “DIDN’T”—“STEAL—“USED”—“INVISIBLE”: they are part of the story, but in the way they are sung—declaimed, hammered, thrown down from the mountain to shatter among the crowd at the foot—each word is also the story itself. You are drawn into single words as if they are caves within the song. Why one word is bigger than another—or more threatening, or more seductive—makes no obvious narrative sense. The words aren’t merely bombs, they’re land mines. They have been planted in the song for you to find, which is to say planted that they might find you. Each word lies flat on a stone in the field, spelled out, “YOU,” “ALRIGHT,” “ALIBIS,” “KICKS,” “THAT,” “BE,” “NEVER,” but there is no way at all to know which one will blow up when you step on it.

Like a waterway opening, the organ comes in to stake its claim on the song halfway through the first verse, just after Dylan finishes setting up the story and begins to bear down hard; just before “You used to/ Laugh about—” The song is under way, the ship is already pitching, and the high, keening sound Kooper is making, pressing down on a chord as it streams into the song, is something to hold onto. This side of the story is just beginning, a step behind the story you are already being told; this sound within the sound tells you the story can’t end soon, and that it won’t be rushed. The sound the organ traces is determined, immune, almost part of another song. “I couldn’t hear the organ, because the speaker was on the other side of the room covered with blankets,” Kooper says, speaking as someone caught up in the uncertainty, the blind leading the blind over a cliff. “I’m used to there being a music director. Having grown up in the studio, there was always someone in charge, whether it was the arranger, the artist, or the producer. There was no one in charge at that session—in charge of the general chaos. I didn’t completely know the song yet. I do have big ears—that was my biggest advantage. In the verses, I waited an eighth note before I hit the chord. The band would play the chord and I would play after that.” But as the song goes on, the organ becomes the conductor of its own drama. For the song it is the shaping hand.

Bloomfield has entered the verse rolling a golden wheel. There is a great glow in the circular patterns he is tracing, but even as the glow warms the listener it is fading into a kind of undertow, now pulling against anything in the music that is still prophesying an open road. Now there is a deep, implacable hum coming from Bloomfield’s guitar, a sound seemingly independent of the musician himself, a loose wire or a frayed connection playing its own version of the song.

No sound holds in the cataclysm the song is becoming; its general chaos is its portrait of everyday life. There is nothing remarkable in the words Dylan is singing so far, no oddly named characters, just someone who once tossed money at people who had none and is now wondering how far she’s willing to go to get some of her own. But as the first verse tilts toward its last line Bloomfield is shooting out of the verse, playing louder than before, hurry and triumph in his fingers. You can feel the song turning, but there is no sense yet of what’s around the turn.

What is around the turn is a clearing, where the musicians charging around the bend find themselves in Enfield, Connecticut, in 1741, with the singer already there to meet them for the chorus—the singer in the form of Jonathan Edwards pronouncing his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” to parishioners who are tearing at their hair and begging him to stop, and the musicians are immediately alive to the drama. “I tried to stay out of Bloomfield’s way,” Kooper says, “because he was playing great stuff. ‘Your next meeeeeal—on the five chord just before the chorus, where he does that ‘diddle-oo da diddle-oo,’ that was a great lick. I didn’t want to step on that. And then he would play that coming out of the chorus, too. The other places, I had room to play, because Michael was not playing lead in those places: in the chorus.” Kooper is still following his own road, but now it comes into full relief; each single line he offers is so clear, moving forward so deliberately, that you can see the track his notes are cutting. The singer is raging and thundering in the air above, paying no mind to anything anyone else has to say but his body absorbing it all, and everything his body absorbs goes into his voice, which grows bigger with every word. Bloomfield’s golden wheel, now bigger than before and even brighter, and more dangerous, a wheel that as its light blinds you will roll right over you, carries the singer out of the clearing and into the next verse. In a minute and a half, a verse and a chorus, more has already happened than in any other song the year has produced.

The feeling in the music in the second verse is more triumphant. Bloomfield’s lines are longer, more like a hawk in the sky than deer leaping a ravine. The rest follow a steady march, and the story seems headed to a conclusion; near the end of the verse is perhaps the most astonishing moment of all, when, out of instinct, out of desire, out of a smile somewhere in his memory, Bloomfield finds the sound of a great whoosh, and for an instant a rising wind blows right through the rest of the music as if the song is a shotgun shack. Is that what allows the singer to whirl in the air, striking out in all directions? There’s a desperation, something close to fear, in the way Dylan throws out “used to it”—the words seem to pull the person in the song off her feet, leaving her in the gutter, stunned, filth running over her, the singer’s reach to pull her out falling short, but there’s no time to go back: the chorus has arrived again. With its first line, those four simple words, how does it feel, an innocuous question, really, you feel that this time the singer is demanding more from the words, more from the person to whom they are addressed. In the verses he has chased her, harried her, but the arrival of the chorus vaults him in front of her; as she flees him he appears before her, pointing, shouting—and the person to whom all this is addressed is no longer merely the girl named by the song. That person is now at once that girl and whoever is listening. The song has put the listener on the spot.

You are listening to the song on the radio, in 1965 or forty years later. “Like a Rolling Stone” is not on the radio forty years after its release as often as it was in the second half of 1965—but you might be able to count on hearing it more frequently in 2005 than you did in 1966, when it was last year’s hit. On the radio, where the tambourine is inaudible, the piano seems like an echo of the guitar, and the organ could be playing to the drums, you can hear Dylan’s up-and-down rhythm guitar and Joe Macho’s bass as a single instrument. Dylan and Macho have heard each other, and they have locked into a single pattern, the bass supporting the guitar, the guitar extending the bass. This is the spine of the song, you realize, or its heartbeat, banging against the spine. It’s the simplest thing in the world: “very punky,” as Kooper hears it. “Ragged and filthy.” But the song must be almost over—the second verse has passed, and the chorus has nearly run out its string. The song has already demanded more from you than anything else you’ve ever heard. You want more, but that’s what a fade at the end of a record is for, isn’t it, the sound disappearing into silence, to leave you wanting more?

Even now, when it is no shock that there is more, as there was when the record first appeared on the radio in 1965, no surprise that the disc jockey is actually going to turn the record over to see what happens, to play the whole thing, as in the first week or so of the song’s release many disc jockeys did not, it is still a shock. The arrival of the third verse, the announcement that the story is not over, is like Roosevelt announcing for a third term.

“Like a Rolling Stone” wasn’t the first six-minute Top 40 hit, or the first to be cut in half and pressed onto two sides of a 45. In 1959 both Ray Charles’s “What’d I Say,” which was longer than six minutes, and the Isley Brothers’ “Shout,” which was shorter, but more dramatically flipped from side A to side B (“Now, waaaaiiiiit a minute,” cried the leader as the first side reached the out groove), were hits, and “What’d I Say” was enormous, inescapable. But these were dance records, not story-telling records. They swept the listener up and carried the listener along, but they did not implicate the listener; they did not suggest that the song had anything to do with the moral failings of the people listening, or that its story was their story, whether they liked it or not. All “Like a Rolling Stone” shared with “What’d I Say” and “Shout” was their length and their delirium.

In Don’t Look Back, in England in the spring of 1965, the film teases the viewer with the notion that you can see “Like a Rolling Stone” first take shape in the film itself. Dylan and Baez and Dylan’s sidekick Bob Neuwirth are in a hotel room; Dylan is singing Hank Williams’s “Lost Highway,” from 1949. It was a rare Williams song that he didn’t write. “Once he was in California hitchhiking to Alba, Texas, to visit his sick mother,” Myrtie Payne, the widow of Leon Payne, the song’s composer, told the country music historian Dorothy Horstman. “He was unable to get a ride and finally got help from the Salvation Army. It was while he was waiting for help that he wrote this song.” With Baez singing harmony, it’s the first time in the film that Dylan seems engaged by a song. “I was just a lad, nearly twenty-two,” he sings, as if the words are his, with a Hank Williams whine that somehow doesn’t seem fake. “Neither good nor bad, just a kid like you.” “No, no,” says Neuwirth. “There’s another verse, ‘I’m a rolling stone.’” Dylan picks it up, and it’s odd that he left it out, because it is the first verse: “I’m a rolling stone, all alone and lost/ For a life of sin, I have paid the cost . . .” But the words “rolling stone” are swallowed up in the tune—“stone” almost fades away as it is sung, wearing down to a pebble as it rolls—and all the words speak for is someone with no will, no desire. Yes, it’s a song of freedom: freedom from family, authority, government, work, religion, but most of all from yourself. It’s a wastrel’s song; not “rolling stone” but “lost highway” is the ruling image, promising that the singer’s grave will likely be a ditch on the side of the road.

In “Like a Rolling Stone” you can’t hear “Lost Highway” any more readily than you can hear Muddy Waters’s 1950 “Rollin’ Stone.” Cut in Chicago, with Waters playing a big-city electric guitar, the piece was pure Mississippi in its tone, its menace, affirming a tension coiled so tightly in the music that when in a brief guitar solo Waters turns over a single, vibrating note, it seems to bite itself. “Gonna be a rollin’ stone/ Sho’ nuff be the rollin’ stone,” the pregnant woman in the third verse chants to herself of the child she’s carrying, snapping off the last word again and again with the feeling of a knife quivering in a wall—unless it’s the child inside her banging on the door, whispering he’ll kill her if she doesn’t let him out. Here the rollin’ stone gets up and walks like a man, and that’s what you hear in Waters’s guitar solo, more even than in the way he slides his voice over the words. You hear someone free from values and limits, never mind mothers, fathers, jobs, church, or the county courthouse. He never raises his voice. You get the idea that if he did—

In folk terms it’s fables like “Lost Highway” and “Rollin’ Stone” that Dylan’s image comes from, but if the image of the rolling stone is what seals his song’s own fable, that image is not what drives the song. As a song, a performance, a threat, or a gesture, “Like a Rolling Stone” is closer to Dylan’s own “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” from 1963, Elvis Presley’s 1961 “Can’t Help Falling in Love,” the Animals’ 1964 “House of the Rising Sun,” Sonny Boy Williamson’s “Don’t Start Me Talkin’” and Elvis’s “Mystery Train,” both from 1955, the Stanley Brothers’ 1947 “Little Maggie,” or Noah Lewis’s 1930 “New Minglewood Blues.” (“I was born in the desert, raised up in the lion’s den,” Lewis sang coolly, as if he were presenting himself as the new sheriff in town. “My number one occupation, is stealing womens from their men.”)

9 “Like a Rolling Stone” is closer to Will Bennett’s irresistibly distracted 1929 “Railroad Bill,” which is fifteen combinations of two-line verses and a one-line refrain in under three minutes, including sets about weaponry (“Buy me a gun, just as long as my arm/ Kill everybody, ever done me wrong”), throwing everything away and heading west, drinking, domesticity, and the outlaw Railroad Bill himself, who never worked and never will. In its headlong drive into the street, its insistence on saying everything because tomorrow it will be too late—to speak as a prophet, someone who, burdened with knowledge he didn’t want but, having received it, is forced to pass on—“Like a Rolling Stone” probably owes more to Allen Ginsberg’s 1955 “Howl” than to any song.

If any or all of these things is a source of “Like a Rolling Stone,” or an inspiration, like “Lost Highway” or “Rollin’ Stone” they say little about why the song is what it is. If there is a model for “Like a Rolling Stone,” it may be in the long, dramatic story-songs made by Mississippi blues players Son House and Garfield Akers—music that, as collected in 1962 on Really! The Country Blues, an obscure, hard-to-find album on the fanatical country blues label Origin Jazz Library, Dylan knew well.

On House’s 1930 “My Black Mama,” more than six minutes and twenty seconds on both sides of a Paramount 78, and Akers’s 1929 “Cottonfield Blues,” exactly six minutes on the two sides of his Vocalion ten-inch, the songs begin almost identically. “Oh, hey, black mama, what’s the matter with you?” says House. “I said, looky here, mama, well just what are you trying to do?” says Akers. Both songs end almost mystically. In “My Black Mama,” the woman who was trouble in Part 1 is dead in Part 2. The singer is summoned: “I looked down in her face,” he says; you can feel her face already rotting. When he sings, in his last verse, his deep voice seemingly deepening with every syllable, “I fold my arms and I walked away,” you can feel him walk off the earth. In “Cottonfield Blues” the woman who was trouble in Part 1 is gone in Part 2; as Akers sings commonplace lines in his high, thin voice, he makes you feel that they have never been sung before. He stretches his words across their vowels so naturally, so inevitably, somehow, that you picture the singer on a mountaintop, singing across a valley, making his own echo, but when the song hits home

I’m gonna write you a letter, I’m gonna mail it in the air

I’m gonna write you a letter, I’m gonna mail it in the air

Says I know you will catch it, babe, in this world somewhere

Says I know you’ll catch it, mama, in the world somewhere

you see that Akers is the letter and that he is in the air, traveling somewhere out of reach of the U.S. Mail.

“My Black Mama” is slow, all of its drama bottled up; as it moves forward the pressure is never released. Akers jumps “Cottonfield Blues” on his guitar, his technique so primitive that for all he has to tell you about Mississippi in 1929 he could be playing in Manchester in 1977 on the Buzzcocks’ “Boredom,” their punk theses-nailed-to-the-nightclub-door. Akers pushes his story so fast you can feel he’s afraid of it, and House makes no effort to hide the fact that he is afraid of his. Each is such an old story—and each is utterly singular. Each man says the same thing: to tell a story, you must take as much time as you need. The length of “My Black Mama” and “Cottonfield Blues” is the axis of their art; when you reach the end of either, you have been taken all the way through a crisis in a certain person’s life. Because the artist, speaking in the first person, has shaped that crisis so that his response to it becomes an argument about a whole way of being in the world, you have not only been through a crisis. Taken to its essence, the artist has described his life as such, guided you through the strange and foreign country of his birth, education, deeds, and failures, right up to the point of death.

With “Like a Rolling Stone” too, its six minutes—six minutes to break the limits of what could go on the radio, of what kind of story the radio could tell; at first the label on the 45 read 5.59, as if that would be less intimidating—is the beginning and the end of what the record is about and what it is for. When the record is over, when it disappears into the clamor of its own fade to silence, or the next commercial, you feel as if you have been on a journey, as if you have traversed the whole of a country that is neither strange nor foreign, because it is self-evidently your own—even if, in the first three minutes, the journey only went as far as your own city limits. The pace is about to pick up.

When “Like a Rolling Stone” smashes into its third verse everything is changed. The mystery tramp who appeared out of nowhere at the end of the second verse has left his cousins all over this one. Everyone has a strange name, everyone is a riddle, there’s nobody you recognize, but everybody seems to know who you are. “Ah, you—” Dylan shouts, riding over the hump of the second chorus and into the third verse; the increase in vehemence caused by something so tiny as the adding of a syllable of frustration to the already accusing “you” is proof of how much pressure has built up. The sound Bloomfield makes is like Daisy’s voice—“the sound of money”—and like Gatsby Bloomfield is reaching for it, but as soon as it is in the air he steps back from it, counting off the beat as if he is just James Gatz, counting his pennies. He is banging the gong of the rhythm as if he is hypnotized by it, each glorious note bending back toward the one before it. As the band seems to play more slowly, as if recognizing the story in the song for the first time—a congress of delegates drawn from all over the land, all speaking at once and all giving a version of the same speech—the singer moves faster, as if he knows what’s coming and has to stop it. He reaches the last line of the verse, holds the last word as long as he can hold his breath, and then as the song tips into the third chorus everything shatters.

The intensity of the first words out of Dylan’s mouth make it seem as if a pause has preceded them, as if he has gathered up every bit of energy in his being and concentrated it on a single spot, and as if you can hear him draw that breath. “How does it feel” doesn’t come out of his mouth; each word explodes in it. And here you understand what Dylan meant when he said, in 1966, speaking of the pages of noise he’d scribbled, “I had never thought of it as a song, until one day I was at the piano, and on the paper it was singing, ‘How does it feel?’” Dylan may sing the verses; the chorus sings him.

With this moment every element in the song doubles in size. It doubles in weight. There is twice as much song as there was before. An avenger the first time “How does it feel” takes him over here, the second time the line sounds Dylan is despairing, bereft and sorrowful, but by now, moments after he himself has blown the song to pieces, the song has gotten away from him. Kooper’s simple, straight, elegant lines are breaking up, shooting out in all directions, as if Dylan’s first “How does it feel” was the song’s Big Bang and Kooper is determined to catch every fragment of the song as it flies away. As the chorus begins to climb a mountain that wasn’t in the chorus before, Kooper finds himself in the year before, in the middle of Alan Price’s organ solo in the Animals’ “House of the Rising Sun,” a record that to this day has lost none of its grime and none of its grandeur. Price’s solo was frenzied, its tones thick and dark; it was a deep dive into a whirlpool Price himself had made, and Kooper is playing from inside the vortex, each line rushing up and out, nailing the flag of the song to its mast.

Nothing could follow this. In the fourth verse, everyone’s timing is gone. The “Ah” that swung the first line of the third verse is here a long “Ahhhhhh” that flattens its own first line. Bobby Gregg, whose drum patterns in the first verse had given the song shape before the musicians found the shape within the song, fumbles as if he has accidentally kicked over his kit. Everyone is fighting to get the song back—and it’s the words that rescue it, that for the first time take the song away from its sound. The words are slogans, but they are arresting, and if “When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose” sounds like something you might read on a Greenwich Village sampler, a bohemian version of “Home Sweet Home,” “You’re invisible now, you got no secrets to conceal” is not obvious, it is confusing.

Confused—and justified, exultant, free from history with a world to win—is exactly where the song means to leave you. There is a last chorus, like the last verse spinning off its axis, and then Dylan’s dive for his harmonica, and then a crazy-quilt of high notes that light out for the territory the song itself has opened up.

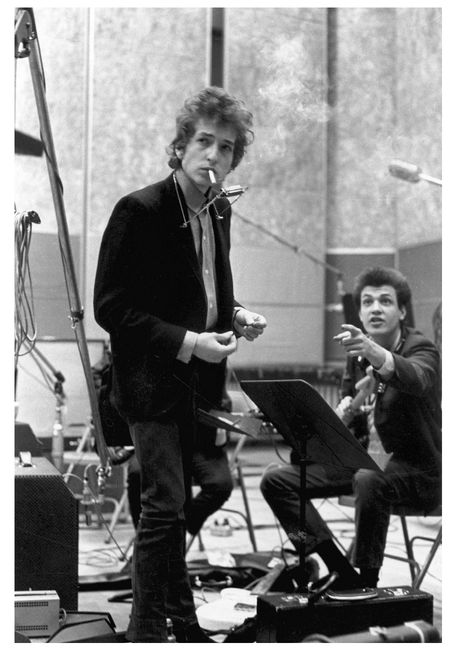

With Michael Bloomfield

Fifteen years later, when Dylan invited Bloomfield onto the stage at the Warfield Theatre to play the song again, Dylan was filled with Jesus, and Bloomfield was just a Jew, washed-up, a junkie whose words were as empty as his eyes, a pariah. Bob Johnston, the producer who would replace Tom Wilson after “Like a Rolling Stone,” was there for the show. Bloomfield approached him. “Can you help me?” he said. “No one will talk to me.” Bloomfield promised he was off drugs, that he wasn’t drinking, that he had gotten his life back, but Johnston had already heard him play. After each phrase from Dylan, Bloomfield fingered his rolling notes, but he couldn’t play the song. In the way that he could only play the record—in the way that he couldn’t hear the music, couldn’t respond to the other musicians, or to Dylan, or to the three-woman gospel chorus, in the way that, like so many Dylan guitarists who over the years, in city after city, have copied Bloomfield’s notes as blankly as Bloomfield was doing this night, he could only copy himself—he was lost, and then he was incoherent, a ruin. But as he so rarely would after the first year he toured with “Like a Rolling Stone,” this night Dylan is flying with the song, energized by the story. As it goes on he hits everything harder:

He’s not selling any al-i-bis

As you stare into the vacuum of his eyes

And say, do you want to, ha ha, make a deeeeaaaallll

He opens the second chorus as if he is unfurling the flag that Tashtego, or Al Kooper, nailed to the sinking mast of the Pequod at the end of Moby-Dick, and as it did in 1965, fresh wind blows through the music. It almost seems as if Dylan is defending the song from Bloomfield—trying to rescue the song Bloomfield must have still carried somewhere inside himself from the broken man who could no longer really play it; defending the song or, from his own side, trying to give it back. “In them you can hear a young man, with an amazing amount of young man’s energy, the kind of thing you would find in the early Pete Townshend or the early Elvis,” Bloomfield said two days before his death, speaking to the radio producer Tom Yates, talking about the songs Robert Johnson cut more than forty years before. “You can hear this in Robert’s records; it just leaps off at you from the turntable.” Was he asking his interviewer to say to him, “Yes, but you played like that, too”? Could it be that in the unfinished fable of the record they made together in 1965, Michael Bloomfield played out the fable of self-destruction in “Lost Highway,” and Bob Dylan the fable of mastery in “Rollin’ Stone”? “Michael Bloomfield!” Dylan said as the song ended that night at the Warfield. “Y’all go see him if he’s playing around town.”