30. shock value

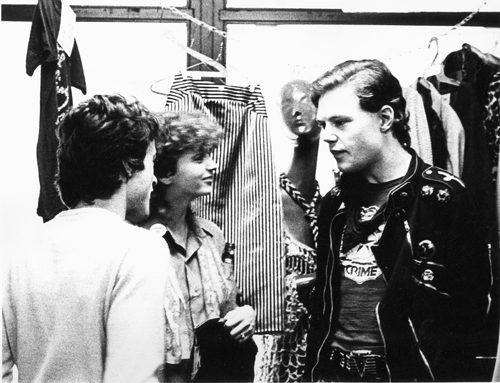

Johnny Garbagecan, Raymi Mulroney / photo by Gail Bryck

Johnny Garbagecan: The Ugly ended up going bankrupt because of the fire at David’s. All of our stuff burned in his club, and then we couldn’t get the insurance money because the owner, Sandy – his partner screwed off to Detroit. So we lost our gear.

Raymi Mulroney: Sam lost his SVT, Tony lost his Premier drums, we lost microphones. I think I salvaged one of my amps and Sam had a guitar underneath the stage that didn’t get burnt. The neck got a little warped from the heat.

It wasn’t until I think about two months later before we got all our equipment back and started up again. It was a real struggle.

Johnny Garbagecan: Our equipment was standing there all charred. Can you imagine that some people came in and actually salvaged what was left of the speakers and stuff?

The insurance was gonna give Sandy a hundred grand. He was gonna buy us all new equipment with that, because it would have only cost about twenty at the time.

Tony Vincent: The Viletones’ gear burned down that night, too. It was New Year’s Eve. I could be wrong because it’s so long ago, but I think it was one of the very few times that we actually played together, the Tones and the Ugly.

After that fire it just seemed like everything went dead, totally dead.

Johnny Garbagecan: The music scene, to me, I thought there was money here to be made. It’s not that I ever want to be rich, but it’s nice to have enough money to eat and live, right? So that was gonna be my thing.

But the fire at David’s changed a lot of things in my life. I think I actually did go and get a job after that fire. I had to go get a job. It was terrible.

Raymi Mulroney: I was working at a hospital. I don’t know what Sam and Tony were doing. Mike was trying to get things back together, like, “What are we gonna do?” He was writing more songs.

Then I guess he hooked up with Billy.

William Cork: The Ugly sounded like the Stooges. At that point Iggy Pop had disappeared and he was a one-of-a-kind item. To me the Sex Pistols just sounded like banging a couple garbage cans together compared to Iggy.

Up until that time I had been a big Doors fan, but Jim was dead and then there was disco. Iggy was mowing lawns somewhere. It was like the end of the world. And then the Ugly came along.

It was a pleasant surprise. Mike, he was beautiful. There were only a few guys like him, like Alan Vega from Suicide was like Mike and there was a guy, an Oriental guy in San Francisco, Winston Tong. They were about the three guys, and maybe later Stiv Bators. They were the only people worth playing with as singers.

Raymi Mulroney: Billy was awesome. A little mysterious at first because I was a young kid and he was older. It was, “Where did this guy come up with this theatre? Where did he get his dough from?” He seemed to be always in financial straights, but he always managed to get something together.

He did have a coffin in his basement. It was a Civil War coffin or something like that. A pine box, basically. They said they had to move it out one day and the people next door saw them carrying a coffin down the street. Ha ha ha, you think about it, it was 1978, ’79, and here they were carrying a coffin down the street. People were just blown away. He’s dressed in skull makeup and stuff. He walked around like that. He used to wear makeup all the time and look like a freak. He’d dress in full leather, buckskin and stuff.

William Cork: Jeez, that’s just me, you know? My earliest memory is watching Boris Karloff as Frankenstein. When I was a kid my bedroom was covered in personality posters of Peter Fonda wearing an iron cross in those Wild Angels movies and shit. So it was a natural evolution, ha ha ha. Especially on top of walking in to see Iggy and the Stooges on a few hits of acid. It all made sense, ha ha ha.

Raymi Mulroney: Like I said, where did this guy come from? All of a sudden, bang, there he is – “I’ve got this theatre, Shock. Let’s do gigs here.”

Ralph Alfonso [StageLife Magazine, December 1977]: Let’s face it, the people behind the established Toronto music scene don’t know the first thing about punk rock. They want to make as much money as possible without bothering to assess the music, the groups and, more importantly, what the public wants to hear.

They’re all crawling out of their little holes in the dirt; instant punk managers, promoters, club owners and other assorted losers who’ve sniffed their way out of their graves for the occasion.

Only one place in Toronto has managed to pick up where the Crash ‘n’ Burn left off and that’s the Shock Theatre. It’s run by people who care about the music and are encouraging the local scene.

Nora Currie: The Shock Theatre had started booking bands. So there were elements of goth and people who were looking for a scene and experimenting with different places. It was a lovely time because it was possible for that kind of integration to take place with scenes and music and styles and art.

So shows there were fantastic. Johnny [Garbagecan] was booking the Shock Theatre. Some fabulous bands came in who hadn’t made it yet, like the Misfits, the Romantics; and again, it was interesting because they incorporated different elements of punk.

They showed horror films at the Shock. Billy was called the Count because he had an infatuation or an obsession with vampires and death and all those things. He used to actually sleep in a casket and when he moved he would move it around with him. He was very good to Fred and Margaret’s son Christopher. Christopher was this little boy and Billy was this total freak. He had all the elements of goth but was much more insane in very positive ways, and very creative. He was a child, as many of us were. A lot of the men I think let their little boy personas play themselves out.

Margaret Barnes-DelColle: My son Christopher grew up in that atmosphere.

Sometimes when I think back it must have been not that great, but everybody really loved Chris. He was just a great little kid and people would kind of borrow him because a lot of people around us didn’t have kids; it was rare to have a child. So a lot of couples would maybe be like, “Oh, we’ll take Chris for the weekend and see what it’s like to have a kid,” or single women would be like, “We’re going to take Chris to the movies or go to the park or something.”

So it was really kind of a communal feeling about everything, and because there were a lot of people in the house he heard a lot of the music and was brought up around it. Probably at the age of six he knew every Ramones song.

Christopher Barnes: I was a little punk rock kid, yeah. Nothing drastic with the hair or anything, but my mother went to college for fashion design so she would make me little bondage outfits and stuff like that.

Margaret Barnes-DelColle: And because we were all dressed up really punk rock, and you never want to do what your parents are doing, he got into this whole thing where he would wear suits. So I’d go out and buy him vintage suits and we would go places dressed in torn up T-shirts and Chris would want to wear a suit. He was six years old, seven years old. It was really funny.

For a while he did modelling; he was in a couple TV commercials and when I would take him for auditions, we were not the typical stage mom and kid. I had purple hair and there he’d be in his little ’60s suit or something. They would always look at us like, “Oh my god, what’s wrong with these people?”

William Cork: I used to live in the Norm Elder Gallery. Norm was Canada’s foremost explorer and different people came to live at the house, like Prince Philip. Norm and his brother were Olympic equestrian champions of Canada.

Anyway, he had this great collection of coffins and he gave me one. For a while I was living in this 1966 Valiant station wagon with a coffin and all my shit in it. That’s when I moved to New Rose, actually.

Margaret Barnes-DelColle: Christopher was six, seven years old and he absolutely adored Billy because he had this collection of horror comics and robots and all these things that a kid would just think, Who is this adult with all this great stuff? He called himself the Count. Christopher would go over there all the time.

Nora Currie: Billy was just in love with Christopher. So here was this adult who slept in a coffin and wore makeup and black and was just insane, in very positive ways.

The Count at New Rose / photo by Gail Bryck

Christopher Barnes: The Count made a big impression on me because he got me into robots and art and stuff like that, and so did Freddy. I never got into music much. I played the clarinet and the saxophone for a while in school. I picked up a guitar and Freddy taught me “Smoke on the Water,” but that was about it.

Yeah, the Count definitely molded some of my tastes. I remember he lived in a storefront on Queen Street and was refinishing his coffin. It was a beautiful old coffin, and I guess some of the neighbours saw through the window that I was in the coffin when Billy was working on it and they called the cops.

William Cork: This buddy of ours, Fred Mamo, had been throwing millions of pot seeds in the backyards. I had been away in San Francisco and unbeknownst to me, I didn’t really look, and there were pot plants everywhere. But I dragged this coffin out to the backyard and I was sanding it with little Christopher and this lady next door, Crazy Mary, phoned the police. I wore a lot of eye makeup and had long fingernails and shit and I was wearing this Crime T-shirt. There was knocking at the door and I walked through the store. I threw the lock on the door and started to walk back to the other end again expecting whoever it was to walk in, but still I see this big figure at the door so I go back and throw it open and it’s these two cops. They ask if they can come in and I go, “Sure,” and I’ve got three days’ worth of melted makeup on and this T-shirt that says Crime across it. They go, “Your next door neighbour has called us.” They go out to the backyard and Christopher’s there, sanding away, and he looks up at the police and goes, “Hey, we build ’em!” As the cops are standing there I’m looking around the backyard realizing they’re standing in this field of pot, right? Ha ha ha, they never noticed, they were so weirded out by this little kid and this coffin and they just left.

Margaret Barnes-DelColle: Christopher was in his glory. He was just like, “Oh, this is cool. This is so great – we’re fixing the coffin!” Ha ha ha.

I’m sure it wasn’t the best upbringing for him, but I just want you to know he’s a pretty stable person today. I think he turned out okay in part because everybody loved him, and it was like having this whole group of adults that were always willing to hang out with him. It was almost like they didn’t treat him like a kid; they treated him like one of them.

Johnny Garbagecan: Billy’s Shock Theatre was going to be all science fiction movies. But Billy smoked too much hash to get anything done so everything was, “Tomorrow, tomorrow, tomorrow.”

Elizabeth Aikenhead: It was like a rundown old cinema as far as I can remember, and it always felt like it was half empty and grungy. At times it felt like there was no one in charge.

At that stage there was a happy atmosphere, it was before things got tense or nasty or scary. It wasn’t political, it wasn’t gangs, it wasn’t violent. It was just fun.

Johnny Garbagecan: I went in there and saw the dollar signs. I went, “Oh great, here’s a place we can practise.” Billy even gave me an office. All of a sudden Shock Theatre was Ugly Headquarters. I had a key to the theatre.

Sam Ferrara: They had a sub-basement there. Tony and I found it. It was this little door and we walked in with our lighters, and there was a little river going down with a little walk space. It just went deeper and deeper and deeper and I said, “Tony, I’m getting out of here, man, I hear stuff in here.”

Karla Cranley: I was an office girl. Very straightlaced. I had just split up with a boyfriend. This girl I knew wanted to go to the Shock Theatre and she thought I was sitting around moping too much at home. So she talked me into going with her, and that was my first physical exposure to punk.

So I met all the guys. I thought the music was great. It was really a wild, exciting time. It was totally alien to me. Raymi and his brother lived out in Scarborough and they all had to lug equipment, so I told them they could stay at my place.

Raymi never left. That was it.

I don’t know what it was that totally fascinated me. I’d been with my boyfriend for four years at that time, so it’s very traumatic when you’re young and you split up. And prior to that, I came from a very bad background and I was married when I was fifteen. I left my husband when I was twenty-one and I went to Toronto and raised our daughter on my own. I had to work seven days a week to keep a roof over her head, and then for four years I was with a guy who ran around on me constantly, always coming home with doses and everything.

But to me, it was still better than my husband who used to beat me into a pulp. He broke my ribs, cracked my teeth, you know? So when I met Raymi, I mean, yeah, he always had other girls, but at least he didn’t bring diseases home and he was honest about it.

Raymi Mulroney: The Ugly had the whole theatre to rehearse in, so that became almost like a rehearsal hall, the Shock Theatre. It was great; Johnny Lugosi was there and Nora was there and Billy and his girlfriend Barb and there was Ruby T’s and Mike and me and Karla and Tony and I forget who he went out with. Everybody had a girlfriend then.

Next thing you know we started getting back our mojo, I guess. Because when you lose everything and you don’t have money, it’s a kick in the head.

Elizabeth Aikenhead: I think, when I started seeing Tony, very quickly I ended up being his girlfriend and getting his clothes ready for his show or taking his jeans in so they were tighter and ironing his shirts because he liked ironed shirts and starch. So I was very quickly in a role where I wasn’t hanging out in the house, and going out with people I didn’t know and that kind of thing.

I ended up living in an apartment with a woman called Karla Cranley above the Varsity Restaurant at Bloor and Spadina. There was a massive Player’s cigarette sign. I remember I was seeing Tony at the time and sitting behind that sign not knowing which bar he was coming from. So I’d be up there with Karla. She was going out with Raymond Mulroney, Mike’s younger brother. She was older and had a child and was a drug addict, so I also ended up looking after her a lot. Very unreliable, and at the same time traditional conservative in some ways. I ended up discovering her in the throes of attempting suicide a couple of times.

Karla Cranley: I became extremely destructive. I couldn’t cope with it anymore. I attempted suicide a couple of times. Ruby attempted suicide a few times. It does something to your head to be exposed to that kind of negativity.

Elizabeth Aikenhead: It was a really depressing apartment. You know, bad lighting and low ceilings and grim carpet and grim furniture.

Karla Cranley: I found it a very, very sad time.

You’d walk into a club, there’d be two hundred people there, and nobody wanted to talk to you unless you were one of the band, like the groupies. Like sycophants, you know? Everybody was always posturing and trying to have a prettier girlfriend or a prettier boyfriend or getting more girls or getting a better gig.

Elizabeth Aikenhead: As soon as I was involved with Tony, I felt so much of my role was not about being in the audience having a great time and having fun. It was very anxious.

I didn’t know what he was going to do, I didn’t know what he was going to say, I didn’t know what was going to happen with the audience, what was going to happen with the band, what the dynamics were about.

Tony Vincent: I don’t know why, but a lot of girls from Jarvis Collegiate used to come down to our shows. There were so many of them. They would follow us all over the place. If you wanted to meet a girl, all you had to do was play in the Ugly and it was no problem.

* * *

Chris Houston: The most desperate of all rock bands would always end up at this one place, which was the Turning Point. Ha ha ha. That was really the bottom of everything.

Don Pyle: The Turning Point was a club that was run by this older Irish or Scottish couple who basically seemed to have the bar as their own rec room, because they were both alcoholics and drunk all the time. It was also such a scuzzy bar that it was completely out of the radar of the police, so they would let anybody in.

Barrie Farrell: The people running the Turning Point were just out of it, so. Ha ha ha. The old lady there would get so drunk she would have her head down – she’d puked, and it was all around her head. She looked up one time and there was nobody there. She looked up again and a fraternity had come in and we were playing there. There were thirty, forty guys with toilet bowls over their heads and bits of things they’d stolen from all over the city. Then she looks at that, puts her head down, Nancy would clean her up, she looks up again, the guys are gone. It was a madhouse.

Don Pyle: It had started off as this coffeehouse sort of jazz thing, and when punk rock came people started looking for places downtown where they could play shows, so they started booking punk rock things. The back wall was this big mural of Jose Feliciano, looking off into the distance with his guitars; a real iconic folk image. There was a very tall stage where anybody could play. The Turning Point was the lowest rung on the ladder of the punk rock food chain. Anybody could play there, it didn’t matter who you were.

The owner was always trying to get people in. He was like, “You’ve got to come in on Friday, we’ve got the Clash playing! Joe Strummer called me and said the Clash were coming!” It was like, “Yeah right.” It never happened, but he would do it all the time. He had this list of three or four known bands that he would use to entice people. “You’ve got to come down this weekend, the Buzzcocks are gonna be here!”

Anne and Joe were the people who ran the Turning Point. They were probably in their sixties. I’m sure they didn’t have a clue how this happened, but all of a sudden their club started being busy. By busy, I mean forty people. The bands that were perceived as being the biggest bands at the time wouldn’t attract more than forty people. The scale of things was completely different. It wouldn’t be unusual to go to a show and there’d be fifteen people there. And you knew thirteen of them, because it was always the same people at the shows.

Tony Vincent: There were always women around the Ugly. Oh yeah, lots. Don’t ask me why.

Suzanne Naughton: Most of the time the bands used to hang out at the women’s washroom, because girls were in there. It’s where I usually saw Steven Leckie. Only the guys with the biggest balls dared to go in there. It was kind of intimidating, though. You’d go in and see Mike Nightmare or Steven Leckie or Tony Torcher necking with somebody against the sink. And it’d be like, I really need to take a leak. Do I really want to do it next to these guys?

Elizabeth Aikenhead: I remember I was just sitting watching the band at the Turning Point, and this one girl came and pulled me to the ground by my hair. I didn’t even know who it was or what it was about. I think they were having a thing maybe.

It really turned; it wasn’t fun anymore at all. Even a lot of the songs I wasn’t listening to. I didn’t know the words anymore. It wasn’t the music anymore. It wasn’t about hanging out in the scene. I don’t even know what the attraction was. It was just hard to get out of. And I didn’t like it necessarily. I was just stuck in the role of starching those shirts and taking in the jeans and running out to Long & McQuade to get extra drumsticks.

It wasn’t long after that that I realized this is no fun, I’ve got to get out of this.

Tony Vincent: I guess you could call me No Fixed Address. I didn’t have a permanent place to live. I just kept going from place to place. I guess you could call me a user, too. I would use girls to stay at their place. I did that for a long time. I guess I could have gone back to my parents’ house but I chose not to.

Karla Cranley: He was a good drummer, and I’m sure he got creative or enjoyed the music, but for him it was more to do a gig to see how many girls he could get afterwards. And I mean, when Tony and Lizzy moved out of our place and tried to make a home, I felt so sorry for Lizzy because Tony was already married and had a wife at home.

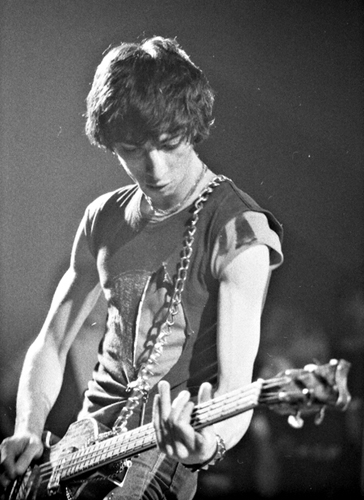

Tony Torcher / photo by Gail Bryck

Elizabeth Aikenhead: He had two kids who were raised by his parents. I found out about his kids when I was having my hair done with pink and green stripes or something at the Rainbow Room. Michael, the hairdresser, said, “How are Tony’s kids?” And by then I’d been living with him for a little while. And I said, “Oh, they’re great, they’re doing well,” kind of not knowing that he even had kids. He’d also lied about his age; he was older than he said he was. Which was fine, I didn’t care, but it was interesting to know that he had two daughters. That was relevant.

He’s basically a really good person. As my mother said when she met him – my mum tended to be a bit of a snob – she spent an evening with him and said, “It’s got to be physical.” Ha ha ha. She couldn’t see an intellectual attraction.

I think I saw that he was a good person underneath everything, and I was young enough and naïve enough to think that I could draw that out and save him. You know the syndrome – girls like bad boys, and I think that was a recurring theme throughout the era for a lot of people.

From there, Tony and I got a basement apartment on Brunswick, and it was also kind of grim but we tried to fix it up a little bit. It was a hundred and eighty-five dollars a month, I remember that. We had hideous ’70s furniture; whatever we could find on the side of the road.

I think I weighed eighty-five pounds back then. I see pictures of myself and feel disgusted. We were all like that. My waist was like eighteen inches. I thought I was fine.

Tony had an anger management issue at times, I would say. There was one day when our landlords who lived upstairs heard stuff, heard him storm out, waited a while, and then came down and said to me, “You come upstairs.”

They poured me a little drink – they were both social workers, I think – and they were young and really nice to me. They said, “You know, you’ve got to really think about where this relationship is going and if it’s right for you.”

Raymi Mulroney: I lived above the Varsity Restaurant with Karla. I had my hell, too.Tony had his Cadillac. Tony always wanted his Cadillac with the suicide doors, Lincoln Continental. We always had to hire somebody to drive our equipment around or get a truck to move the stuff around.

Elizabeth Aikenhead: I remember Tony and I bought a Cadillac convertible from his uncle – I don’t know what he was involved in, but I’d say it was something nefarious.

We were driving back from I think Steve and Eva’s one night and he was driving. Out of the blue, a car came and smacked us. Because of the angle, our car was totalled, but the guy insisted on calling the police. That’s when I discovered that Tony didn’t have a driver’s license because it had been taken away many, many years earlier. He told me to lie and say I was driving.

It’s the only encounter I’ve ever had with the police. They took us into separate rooms and there was a really kind, older police officer who gave me a real talking to. He said, “This guy is asking you to lie for him. Lying,” he said, “is a criminal offence. But he’s got a traffic charge, that’s not a criminal offence. You’re heading towards being a nurse.” He said, “Don’t do it. We know he was driving.”

So they brought Tony back into the room and asked the question again – “Who was driving?” And Tony said, “Well, fine, I’ll take the rap.” And the police officers nearly lost it. Ha ha ha. And he’d had a couple of beers or whatever. In those days going to court was a two-hundred-and-fifty-dollar fine, it was nothing.

Which reminds me of going to court for Mike and Ruby. Mike was being charged with B&Es or something. I guess it was also the spirit of, “Oh, this is a big adventure.” Sort of a novelty. We’d get dressed up and go to court with the boys to support them. We were nineteen-year-olds and we probably looked like freaks. Ha ha ha.

Mike was bad news. There was no real novelty in that.

Johnny Garbagecan: Mike was so drunk he went to a party, but he was at the wrong house. He was making a sandwich in this house and I guess he was probably wondering where everybody was, and the next thing you know the cops were there. He missed the party by a block. He was just making himself a sandwich and I had to get him bailed out because we had all these gigs coming up.

Somebody asked him what made him that way and he said, “If I wasn’t into rock ’n’ roll, you guys would be laying on the floor right now and I’d be stealing your wallets.” It was either he was in a rock band or he was a criminal. It was gonna be one of the two, and sure enough he died a criminal. We did an interview for the CBC at the office at Shock Theatre and it was on the six o’clock news. Mike’s mother heard it and she almost had a heart attack.

That was the part that ended up on the radio. So you can imagine his mother – they were Catholic, went to Catholic school and all that business – so really, it was that or the other.

Sam Ferrara: CREEM magazine interviewed us at the Shock. Tony went nuts. This person said, “Can I have an interview?” Tony picks up this bottle and just smashed it right beside this person – “Interview that, you fuck.”

Tony Vincent: The guy in CREEM said, “Check out the Ugly – they are truly ugly.”

Jeffrey Morgan [“A Consumer Guide To Toronto Punk,” CREEM, February 1978]: These bunch of nodes are led by Mike Nightmare… Sure, he’s tough looking but, then again, who isn’t these days? (And, yes, the band members are indeed ugly).

Sam Ferrara: We had a gig at Shock Theatre once and the cops were after Mike at the time, so the poster was him with a leather mask so the cops wouldn’t recognize him. It wasn’t for a gimmick, it was just to get the cops off his back. Ha ha ha.

Raymi Mulroney: Yeah, we had to hide him under the stage once at a gig. The detectives were looking for him. I don’t know what for, so he was under the stage hiding until they left and then we started the gig. They knew I was his brother and stuff, “But I don’t know where he is. We’re doing an instrumental tonight.” Ha ha ha.

Tony Vincent: A lot of people knew Mike did B&Es and stuff. It made a lot of people afraid to approach the band. That’s a reason why record companies wouldn’t touch us. They were kind of cautious about us. They didn’t know what would happen if they actually signed us.

Elizabeth Aikenhead: Mike Nightmare was a troubled soul, I would say. He was similar to Steve Leckie in some ways, as the leader of a band, in that he liked to ignite things. He liked to incite trouble if he could. I guess he had a certain charisma; I didn’t see it, I didn’t get it, but it seemed there were certain guys …

Sam Ferrara / photo by Ralph Alfonso

“Punk Rock: It’s Dying in Toronto Before It Was Born,” by Don Martin [Ryerson Review, September 23, 1977]: Mike Nightmare, lead singer of the Ugly, typifies the male punk rocker. With his black leather jacket, torn T-shirt and chains draped around his neck he claims to be one of the true punk rockers in Toronto. He comes from the street and has no home, but usually ends up sleeping with one of his followers at her place.

“Punk is walking a tightrope,” he said. “Everyone in the punk scene is scared because they don’t think it will last. But it’s up to the punkers to make it last and to make it popular.”

Tony Vincent: People considered us better than the Viletones, like a more authentic punk band. We had more power than the Tones. We were louder, more powerful, and more disgusting. Put it this way: the Viletones, we made them look like nuns.

Raymi Mulroney: Diodes never played with us. They wouldn’t play with us for some reason. They had that real pop sound and we were just too hellish. And then Arson, a band called Arson, the Hate, the Mods and that. And then of course the Toyz, the Brats. We were all over the place. We were probably the most played band around, but we weren’t one of the most recognized bands because our music wasn’t commercially acceptable, I guess. So that’s what I meant about not being taken seriously. Mike was just too wild. People were just shocked to shit.

Tony Vincent: We didn’t want to send any demos to any record company. We didn’t want to belong to a record company, we wanted to do it ourselves.

Mike Nightmare [“Punk Rock: It’s Dying in Toronto Before It Was Born,” by Don Martin, Ryerson Review, September 23, 1977]: I don’t think it will die out, but I see it getting more sophisticated. There will be some really great punk artists and from there it will get big, really big.

Right now punk is new. People are trying to attract attention so they shove a safety pin through their cheek or they cut themselves. But this doesn’t mean that punk has to stay this way. Right now it is an act, nothing else. Someday it will change and become a form of art.