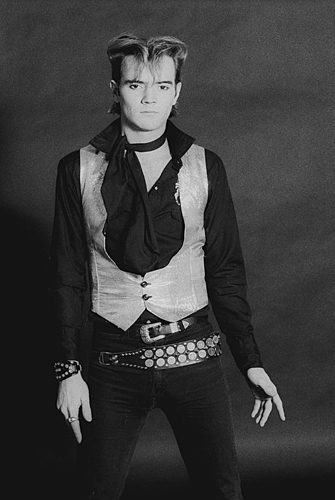

52. fashion victim

Steven Leckie / photo by Edie Steiner

Freddy Pompeii: Another reason we wanted to disband the Viletones was Steve wanted to go into the next big thing, which was rockabilly. He wanted the Viletones to be a rockabilly band, which I thought was kind of stupid. What you’re doing is you’re jumping on every trend that comes down the pipe, so obviously you’re never gonna get out of Toronto.

I knew even when I was a teenager not to follow trends too closely and to just be yourself, and eventually something’s going to come to you. There was no trend to speak of when we put this band together. The Ramones had long hair. It was our own thing; it just so happened that the Sex Pistols beat us to the press.

But he’s definitely a fashion victim. That’s one of his biggest drawbacks. He changed with the trends on cue and it’s not a good way to be, especially if you’re in rock ’n’ roll. You’ve gotta stick to your guns.

When the Clash came out he wanted to be the Clash, when the Pistols came out he wanted to be Johnny Rotten. All of them. Every band that was coming out that was considered underground, he wanted to be. He would just change weekly. Change his whole stage persona, which kind of worked out for him because he started to become known as an improviser.

But people just didn’t know he was stealing it from everyone else, because word didn’t travel on this kind of thing too quickly.

He ripped off a whole song from the Jam. It’s called “Girl Won’t You Let Me,” but it’s actually a song by the Jam called “Away From the Numbers,” on the very first album. He says, “Let’s do this Jam song just to prove we could do it.” So I learned it and we taught the band and we did it. And he changed the lyrics and told everybody he wrote the song, which is a big copyright breach. You just can’t do that. Eventually somebody’s gonna sue you. He tried that a few times where he would come in and say, “I’ve got this real neat riff,” but it was something that he got from somebody else. We would find out and then we would nix the song.

But just because he read something in a magazine like New Musical Express and Melody Maker, which came to the United States and Canada a short time after they were published, that news never got to the mainstream press for months. So he would find out what the latest trend was in England and then put his own spin on it to make it look like he came up with the idea, and it worked for him for a while. Until he got with people who were looking at the same stuff he was looking at.

It was real childish; he was always doing that stuff. That’s why I say he was definitely a punk rocker. He wasn’t sophisticated in any way, shape, or form.

Ross Taylor: I would go with Steve to see all sorts of shows. Steve Martin, the comedian, came to town. It was when he was big on Saturday Night Live. For some strange reason Steve wanted to go, and he and I went and sat in the fifth row. The article in The Star the next day talked about how Steve Leckie was at the show. It was quite amusing.

Gary Topp: The good thing that came out of that punk scene and the developing new wave or whatever you want to call it, was, as opposed to kids now, that specific generation had the benefit of hearing the music of the ’60s and music of the ’50s and even earlier. That generation of kids were open to all forms of music, so you’d get bands like the Stray Cats, bands like the Pogues, Sun Ra.

So those kids who started out sort of punky or totally alternative in the true sense were infusing all this different music that they had heard or were interested in learning about into their music. That was a great part of those days in promoting music. You could bring a rockabilly group totally unknown from England. We were promoting that way, anyway. So all that infusion of different music was what I think kept that particular music alive and developing.

Steven Leckie was totally into rockabilly. It was a big, major influence on his music and his look.

Andrew McGregor: There wasn’t a lot of rockabilly in Toronto. I remember Jack Scott played at the Horseshoe one night. The Cramps really re-introduced rockabilly here and they did some fantastic shows at the Edge, and that kind of got people into rockabilly in this area.

Ross Taylor: Steve had a very wide range of musical tastes. He loved rock music, but he also loved a lot of the old ’50s stuff.

Then he got into rockabilly. When I would go over to his house he would always play these old rockabilly albums, and he was into Elvis like you wouldn’t believe. He was a closeted Elvis fanatic. I think it was the showmanship and the whole lifestyle.

Freddy Pompeii: He did a version of “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” Somebody was turning him on to Elvis records and he wanted to sing like Elvis, but he was not capable of singing like that. Ha ha ha.

Mike Anderson: He never talked to me about that. I had no idea that was going on. I guess that was a trend that started happening with Handsome Ned.

Freddy Pompeii: There was no way I was gonna play rockabilly. It was like country music compared to what we were playing.

Ross Taylor: But as the band changed, especially when Steve Koch joined, this rockabilly movement going on in the UK at the time was a scene Steve was particularly attracted to. When Crazy Cavan came to Toronto, Steve was just like, “That’s it. I’m really going to start working on this style of music and start playing it.”

Jim Masyk, Steven Leckie, Handsome Ned / photo by Ross Taylor

Steven Leckie: It was time to make a decision. The Pistols were finished. The Clash were kind of going reggae, which of course we wouldn’t do. But the rockabilly thing – and there’s a certain way to play it, like English rockabilly, that’s really, really glittery – it’s really cool, and that’s the area we were more focused on.

Captain Crash: The Dog had unbelievable insight. I remember we’d argue as a band. We were trying to figure out a path to take. Where to play, where to go, who to talk to. And the Dog would say, “No, we gotta go this way.” And the four of us would say, “No, man, no, lookit, we gotta go this way.”

The Dog would argue until he was blue in the face and a year and a half later, the fucker was right. He had that insight.

Blair Martin: When Steve put out his first record, they knew they weren’t going to be playing like this forever. You changed every couple of years. Nothing is going to stick around. You weren’t going to be doing this five years from now.

None of us were punk rockers, really, except for the two days, in Steve Leckie’s case, it took him to get his fuckin’ picture in the paper. And after that, he was an aspiring rock ’n’ roll singer.

Ross Taylor: During that period we met a fellow called Handsome Ned. He wasn’t Handsome Ned at the time, he was Robin Masyk and his brother was Jim. They were in a band called the Velours at the time.

We were watching Crazy Cavan at the Edge and Steve Leckie’s sitting here, Robin was sitting here, and his brother was on the other side. And every time Crazy Cavan finished a song, Robin would give me an elbow and say, “We do that! We do that song!” I was getting fed up. He was in Mr. Green Jean coveralls and a straw cowboy hat and he looked like he just fell off the turnip truck. I said, “So who the hell are you?” after he was doing this all night, and he said, “We’re the Velours.”

Steve and Robin started talking and we found out that yeah, they were playing around and they were doing a show that week at the Ontario College of Art. So we went to see them, and sure enough this guy could sing. He had a voice that was unbelievable; he just floored us. The band was so-so, but when Robin sang he did have a voice like Elvis. It was deep and rich and powerful. Steve was actually quite taken with him and started having those guys open. This fusion – they were really a rockabilly band with country influences; Robin had spent time down in Texas and was unbelievably influenced by Texas music – that style of music started creeping into the parties we would go to and the scene we hung out in.

Tony Vincent: I went along with it because I was in the band, so it was either I quit or keep playing.

I did it because Sam was in the band.

We played a lot of covers, rockabilly covers. It was Steve’s idea to do it. He was wearing smoking jackets and sideburns and sparkle socks and he had a waterfall [hairstyle]. We called him Squiggy from Laverne and Shirley because that’s what he looked like.

We got away with it. I don’t know why.

Sam Ferrara: There was a lot of energy. Tony and I had been playing together since I was sixteen. We knew what we were gonna do next without even looking at each other, it was so tight. And Koch on guitar just topped it right off.

The rockabilly stuff was powerful. We didn’t get a good hello for that; I think we started it too soon, because no one was really listening to rockabilly at that time. People were throwing stuff at us, yelling out for old Viletones songs.

Steve Koch: The big gig, the Gang of Four / Viletones / Buzzcocks gig, a lot of people had bad memories about that. But I thought we played well and presented our rockabilly-Viletones thing well.

I know people threw bottles at Steve. It was a test of wills, kind of. Steve had basically decided that it was time to wrench the Viletones out of doing the same songs over and over again and we needed to do something different; we were getting stagnant. He wanted to do some rockabilly and some country stuff, but pump it up because obviously Sam and Tony are like the Who, so whatever they do is gonna be loud and fast. We’d been gradually working these songs in, but this was the big presentation of those songs to a big audience and people were just not prepared to go for that. It was not his time.

But hats off to him. When Steve Leckie said, “I’m gonna do a Hank Williams song,” that was probably the most punk thing he did the whole time I was in the band. That was very courageous, and rather than muddle along with the same old crap over and over again, let’s take on a challenge.

But his audience was not prepared to go along with him.

Blair Martin: The guitar was still on a Marshall amp, but it was still rockabilly. It was like finding a way to grow up; find new interests.

Wayne Brown: I remember one of the nicest Viletones shows I’ve ever seen – ha ha ha, “nice” – one of the best Viletones shows I’ve ever seen was at Convocation Hall with Steve, Sam and Tony. At the time they were experimenting with a bit of a punkabilly sound, and it was good. It was really good.

It was probably one of the biggest shows Steve had ever done, and I think because they were playing Convocation Hall they were all on really good behaviour, probably for a few days before, and they really shined on that show. And they looked great. They looked so amazing. They had a little bit of that rockabilly look to them. Yeah, they looked really hot at that time.

Ross Taylor: Steve Koch was fortunately a proficient-enough guitar player that he could actually come up with the things required to play that kind of music, which wasn’t just the flat three-chord thing like it had been prior to that.

But it didn’t go over so well with the fans, initially. It was a big show; huge sellout, thousands of people there. Steve Leckie comes onstage wearing pink pants and a gold smoking jacket doing the Elvis Presley moves. The fans were booing them and everything else. I remember at one point Sam screaming at Steve onstage, “Let’s do ‘Screamin’ Fist’!” Steve stuck to his guns through the whole thing.

Steven Leckie: I think the people that loved us for the “Screamin’ Fist” type thing really hated it, but it seemed to be the smart thing to do. I mean, they didn’t really know how to take it because the first time we showed it, it was at a show with the Buzzcocks and Gang of Four and everything so they were expecting us to be …

But I came out in all haute couture rockabilly clothes that Eva made me; devastatingly great fitting, I mean really dead accurate, true ’50s stuff. Elvis would have worn this. And that’s how I came out, in the whole nine yards. But after a while I think people kind of, they kind of dug it I think. And Handsome Ned was coming up by then, too, so it created an atmosphere.

“Viletones Play Punkabilly for Puny PCH Crowd,” by Geoff Gordon [University of Guelph At Guelph, 1979]: The group that at one time was banned from playing in New York for promoting bar-wrecking brawls made an appearance at Peter Clark Hall last Wednesday night.

People seeing the Viletones for the first time were in for a major disappointment. The band under Steven Leckie’s (formerly Nazi Dog) tyrannical guidance has moved from extreme punk into something mellower called “punk-billy.”

Throughout the band’s violent early days, Leckie would go home to his Gene Pitney albums and get down to his early rockabilly favourites. It is in this direction that the Viletones are moving. As much as Leckie may enjoy listening to rockabilly, the Viletones are just not suited to this kind of music.Close to one half of the first set was devoted to rockabilly. As much as the audience seemed to enjoy the music, the group did not seem to be as relaxed as they were when punk was played. The second extremely short set, though interrupted by a broken guitar cord, was much more fun, possibly because more punk was played.

Perhaps the reason the Viletones didn’t go over too well was due to the fact that Peter Clark Hall witnessed the sparsest crowd of the year. Also, Bobby Lewis, Viletones’ guitarist, was playing his first show with the band after spending some time with the Androids.

The best examples of the Viletones’ rustiness occurred when they were playing some of their older tunes such as “Possibilities” and “Dirty Feelin’.” Even so, the band has the talent and ability to go places. They sure could use a better drummer, as the present one is pretty talentless.

To illustrate what a wipe-out the night was for the band, they simply knocked over the drum kit and threw their guitars on the ground at the end of the show. Maybe some night with a larger, more responsive audience, they could show the people of Guelph a little more of what punk was, and reveal how commercialized their rivals, Teenage Head, have become.

Editor’s Note: Due to poor attendance of the Viletones pub, the Rex Chainbelt pub, scheduled for Wednesday night in PCH has been cancelled.

Tony Vincent: There was a write-up in the paper about the Viletones playing rockabilly. Steve’s really into press. He doesn’t care if he’s lousy, he doesn’t care if people pay him, as long as he gets press. That’s all that Steve cares about is the press. He loves having his picture in the paper, which I don’t care much about. I just want to play music. I don’t want to be a rock star. I don’t want to have a write-up about me in the paper or a picture of me in the paper. I don’t care for that stuff. I’ve never, ever wanted to be a rock star. I just wanted to be a musician.

* * *

Steve Koch: I think we got Crash to drive us down when we played Hurrah’s. It wasn’t a real memorable gig. It was more memorable as an experience just to play New York City.

Sam Ferrara: I met Woody Allen there. I didn’t know it was Woody Allen, though. We came in and we had all the equipment and stuff, and there’s this guy sitting at this table with a big lineup of people. I wanted to know where the bathroom was so I figured this guy looks important, so I go up to him, “You know where the bathroom is?” He just looks at me and points.

I come out of the bathroom and Steve Leckie goes, “Don’t you know who that was?” I go, “The guy who knew where the bathroom was.” “That was Woody Allen!” “Oh, I don’t like him much, anyway.”

New York was fun. Steve almost got us killed, though. We were in this restaurant, really late at night, and he picks a fight. He doesn’t know that this guy is friends with the whole restaurant and I’m going to Steve, “Shut up, will ya?” And the guy just looked at us and handed us some crosses and said, “Leave.” “Let’s go!” That was creepy.

Steve Koch: And we had a ton of fun playing in Montreal. We got in lots of trouble. Lots of fights and trouble.

Nip Kicks: We played a bar there, the Hotel Nelson, and the bar itself was one of those suspicious bars. Rumour was it was run by the Dubois brothers, who had kicked the Italian syndicate out of Montreal. And when we got to town I remember one of the people there said, “Don’t worry about anything, everything’s taken care of, have a great time.” And the implications seemed to be that basically you could do whatever you want, and don’t worry about repercussions. They basically gave us almost whatever you wanted, and for Tony that meant smack. And that was a bad weekend for a lot of reasons.

Steve Koch: The band that opened for us was called the Electric Vomit. So if that was an example of the scene, there was no scene.

Rick Trembles: The Viletones were violent. Steve was violent. The band that I was in opened up for them. The Electric Vomit. We were all sixteen or something. We were kids. We hardly knew how to play.

We did our set and they come and they had their beers on their amps. Just the volume they were playing at would make the beers fall down and roll around on the floor. We were right in front and our drummer would pick up the beers and put them near him with the intention of saving the beers and giving them back to the band after.

Nazi Dog takes the mic stand and just shoves it really hard into our drummer’s face. I was right next to him, and the mic stand shattered my beer that I was still holding. So I’m left standing there with a broken bottle, and our drummer took off because he was in shock. It was the first punk rock show he’d ever been to, and I was contemplating tossing my broken beer right at Nazi Dog because I was so pissed off; you know, the adrenaline starts going when you’re attacked. He thought we were stealing his beers, apparently. So I look around and there’s all these fans that came in with the Viletones; either fans or bodyguards or roadies, I don’t know what, but they were really pumped up and getting into this potential confrontation. One of them looked like a body builder and all decked out in leather and he was just looking at me, smiling and making fists. He looked like he was going to tear into me if I did anything, and enjoy it. He looked way bigger than me.

So I just threw the bottle onto the floor and took off. It was a three-night gig and we had to open for them the next night, and our drummer didn’t want to do it anymore. He chickened out, he was so pissed off. He said, “If this is punk rock I’m outta here,” so we had to get a drummer at the last minute.

We did the show and our singer ran after [Steve] the next night and demanded to know what happened, and demanded an apology. Our singer used to stutter, so it must have been really funny. We hardly knew how to play and we looked like a bunch of nerdy kids, and these guys were trying to look really tough and they had this badass reputation. They must have thought it was hilarious to have this singer come up stuttering, “W-w-why d-d-d-did you d-d-do that?” Anyway, he apologized, finally. He just said, “Sorry, I thought you were stealing our beers.” Which doesn’t really excuse it much, but …

It was that drummer’s first punk rock show and he was trying to be nice.

Steve Koch: What else? We’re walking down the street and a bunch of us get into a fight with a local guy. Somebody threw a tire at us. I’ll never forget that. Why are you throwing a tire at us? That must be really hard. And then he ran away.

Sam got run over while he was in a cab. A bunch of people are piling in the cab and he’s the skinniest guy in the world and he’s not completely in the cab and the cab goes and his foot goes – foop – around the tire of the cab and it breaks his foot. So he got run over by the cab he was in. He went to the hospital and they said it was just sprained. He gets back home and it’s not sprained, it’s broken.

He’s always got a broken foot. There’s a million pictures of Sam with a broken foot. He’s fragile.

Nip Kicks: Sam actually got his foot run over by the cab he was in, ha ha ha. It was one of the most bizarre things I’ve ever seen in my life. But that was another case where, I’m not even sure of the chronological order because it was the first and last time I did smack.

I could appreciate all of a sudden, in that moment, how dangerous it was because it felt so good. I have to admit, I didn’t care about anything for that short period of time.

Luckily, being a control freak, I didn’t want anything to do with that anymore.

But I’m also pretty sure that weekend we had Tony in the shower and he’d OD’d. That was a bad scene.

Tony Vincent: Heroin started to come in right after the rockabilly stuff.

I OD’d three times. The first was in Montreal and someone took a picture of it. I saw it, and my face was purple. Someone threw me in the shower and I started coming back. Then another time I was with my friend Jeff, and he started dragging me around. Someone saw it and said, “Man, what are you doing? You’ve got to call an ambulance.” All I remember is being with Jeff, and then I woke up in the hospital with this bracelet that said “Mr. X.” I didn’t have I.D. or anything on me. Another time I OD’d a girl punched me in the heart and brought me back. It was the drug of choice then, yeah. A lot of people were doing it in the scene. It’s like peer pressure.

Steven Leckie: Tony Vincent, in that era of the Viletones, wakes up in Montreal and the girl beside him has overdosed and died. She’s swallowed her vomit. Montreal homicide squad, the whole nine yards, it’s very self- evident it wasn’t a murder, we see what it is. That was just a day in the life. When you have that kind of speed, it would have made anyone in Guns n’ Roses blush.

I’m surprised all eight of us are alive, but I guess what kept us alive was the intellect; the knowledge that we’re dealing in art here.

Elizabeth Aikenhead: I think one of the first times I realized heroin was around was at Freddy and Margaret’s store.

It was a Sunday afternoon. We were hanging out there and I think Tony and some people had gone upstairs. And I remember being totally freaked out and really disturbed by the image of a belt around an arm and the end of that belt in his mouth. The guys were almost panting over the extended arm. That image really, really disgusted me and horrified me and disturbed me. That was crossing the line.

Then I remember hearing about the next incident at the Hotel Nelson in Montreal. One of the guys overdosed and they had to walk him in the shower and do all that stuff, and I heard about this later. So that was very upsetting again.

And then hearing about people compromising their values and their integrity to buy drugs. And often it would be a one-time thing – “An old, old friend from Scarborough came to town, got something, it was on the table …” There was no resistance, even if it had been months, years; that allure was so powerful.

I just loathed that. I found it almost physically repulsive. And seeing that with Karla as well, completely together and then getting into speed and compromising everything that you say you believe in and all the responsibilities that you go on about; throwing it all up in the air and hurting so many people.

So I just said, “Okay, that’s it.” There was no hope, that’s it. I think as a young woman who somehow felt a role and a need to be needed, or a role in being useful and helpful to people, that’s when I realized there was no point. You can give as much as you can, and then there’s no point.

Gambi Bowker: I think a lot of people were just thinking, This is the new drug this year, and those were the people who unfortunately ended up having severe problems with it or died.

There was an old-school crew in Toronto that were involved; they were the older ones on the scene, but it was kept quiet. It wasn’t something that everybody knew, and you didn’t have people shooting up in toilets at the Horseshoe or the Cameron House. The people doing it were doing it for themselves, and that was it. It wasn’t part of the scene.

Unfortunately, a lot of people who got involved with it thought, “Because those guys are functioning, they’ve been junkies for years, I can just have fun with this.” And it’s not a drug to have fun with.

Elizabeth Aikenhead: [Our neighbours] Ellen and Raymond came over and they gave me this little cat that we called Ringo. I used to joke that the cat was such good company I didn’t really need Tony around. So we lived together with this cute little tabby in the basement. The biggest piece of furniture was Tony’s drum kit in the bedroom. It was massive.

Before long Ellen and Raymond had a friend who was moving out of her great apartment on Avenue Road. It was a nice second floor with two bay windows, so I moved into there and was trying to break up with Tony at the time. Before long we did, which was great, but it was very difficult once and for all to say it. As one friend used to say, “You guys were up and down like a toilet seat.” Tony had really tried to clean up his act and be together and be the good person that he is, but it wasn’t meant to be at all.

So I moved into that apartment. It was fantastic. I tried to make it home and Tony helped fix it up, but we were over. There were some drug issues that I wasn’t prepared to accept at all, so I found a real strength and was able to say, “That’s it.” Sam Ferrara was instrumental in helping me out on a couple of occasions with Tony, because Tony trusted him and loved him and so was able to accept Sam’s support and leadership in that situation. So I’m forever grateful to Sam.

Nip Kicks: There was a lot of trials and tribulations going on there, especially with Sam, who loved Tony dearly but was having a real struggle with the heroin. And again, I was lucky because that was my one taste and that was it. When I came back I think I slept for three days after the Montreal trip.

At that time not too many other people in the scene were doing heroin and it hadn’t really invaded things at all, but boy oh boy, it hit large later. In the early days it was all bennies more than anything else; bennies and beer. For the most part that was the stalwart as far as drugs go. Coke hadn’t really made its big influence yet.

But people weren’t there for the drugs, they were there for the music, and that’s the difference. In the early days you’d go and see all the flyers you could find on who was playing where and where your friends would be, and there were only two or three joints you could go to. Then I started seeing that people were going out looking for the parties, not the concerts anymore. It became the parties, and that was a switchover.

Sam Ferrara: I think the audience was more violent than the bands. There were times like backing up Iggy Pop in Montreal, I had a beer can right in the head, a full one.

Yeah. They totally sabotaged that gig. I doubt it was Iggy Pop who did it; he’s a nice guy.

Steven Leckie: I was playing with him in the St. Denis Theatre in Montreal. He’s pretty hip. He knew what I was up to, and the Dead Boys. And I guess that’s pretty well all there was on the horizon: Two younger bands that were trying to go for the specific crown of Iggy himself.

They did [sabotage that gig], absolutely. Yeah, you know what they did? It was sold out of course and while we were on the stage, the house lights still on, they open the doors and the kids are running down to get their seats. And the reason was because the crew at the St. Denis Theatre turned out to be the same crew that worked at a big bar in Montreal that I played in with the other Viletones, with Chris and Freddy, and that bar got closed down after us. That’s why it was sabotaged.

Sam Ferrara: We go on and nothing is miked except for Steve’s microphone, house lights are still on, and we must have sounded like a little transistor radio on this big stage.

Rick Trembles: It was really hideous. The music seemed to have degraded even more. Everybody was hyped for Iggy Pop, and the Viletones come on.

Sam Ferrara: So people started throwing shit. I think we got through maybe three songs, not even, and we said, “Fuck this.”

Rick Trembles: For one thing, probably the audience figured it’s Montreal, how come there wasn’t a Montreal band opening? If you have the Viletones, they’re not that great. You could’ve given a Montreal band a break.

The audience tore into the Viletones; they just despised it. It was non-stop booing. I remember they had some guy who looked like a throwback from the mid-’70s with platforms on; he looked like a clown. Everyone was booing them and being brutal.

Steven Leckie: They let the kids in. They wanted them to see behind the curtain and not let us have any magic. And then they wouldn’t give us the full effect of the sound and lights, and that would be a direct result more I think of a managerial decision on Iggy’s part. I wouldn’t do that. It would be my best interest to hype up the opening band, I think. But in those days, the way to defend yourself would be to make sure, especially the Viletones and Dead Boys, couldn’t come close to what Iggy was doing.

He’s a real fuckin’ prima donna; he’s just a bit of a prick that way. I would have been worried, too.

Rick Trembles: A couple years after the Viletones there was a movie – I’m not sure if it’s Crash ’n’ Burn – about early Toronto punk in black and white playing in Montreal. I brought along a small mickey of Southern Comfort; I thought I was going to end up partying the same night after the movie, but I really wasn’t used to hard alcohol. I was kind of young still. I got wasted and went to the movie, and as soon as the Viletones came on I remembered that episode with the mic stand in the face and I got all pissed off and I was yelling at the screen, trying to get payback for what Nazi Dog did.

Everything started spinning and I found myself rolling in the aisles yelling and yelling and yelling, “FUCK YOU, VILETONES!”

The next thing I know, the cops are escorting me out of the theatre and I end up in the drunk tank overnight. I wake up the next morning with puke all over my shoulder and the cops just said, “Goodbye, you’re free to leave.” Go back home to my parents’ where I was still living, all covered in puke.

So I got back with the Viletones. We’re even now.