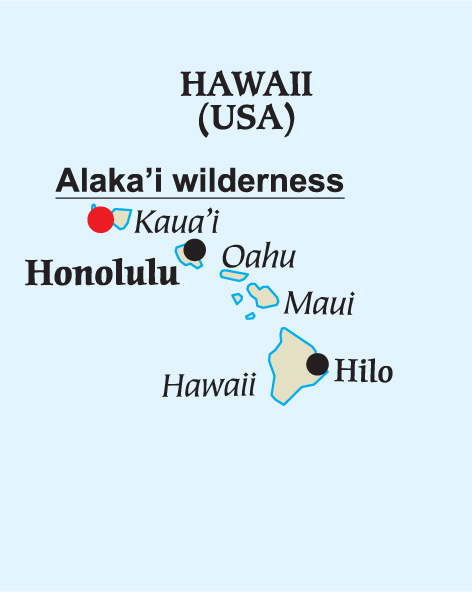

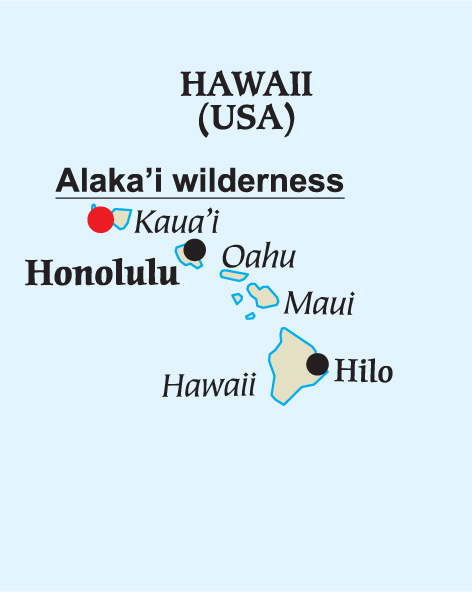

USA

Alaka’i wilderness

Information

SITE RANK

6

HABITAT Montane forest and bog

KEY SPECIES [Kauai] Elepaio, Puaiohi, Kauai Amakihi, Anianiau, Akekee, Akikiki, Iiwi, Apapane

TIME OF YEAR All year round

Elepaio is a member of the monarch family, which is found mainly in Australasia.

The 50th state of the USA, Hawaii, is situated more than 3,000 km from the nearest landmass, in the middle of the North Pacific Ocean, making it the most isolated archipelago in the world. Not surprisingly for such a remote place, the birdlife is very special indeed, containing, among the land dwellers, almost nothing but endemic forms. These forms include one completely endemic family, the Hawaiian honeycreepers, which present perhaps the most complete example of avian adaptive radiation in the world. From a single colonization, the honeycreepers’ finch-like ancestor evolved into a family of birds showing profound differences in bill shape, colour, vocalization and ecology – indeed, a much more impressive variety of forms than the better known Darwin’s finches of the Galapagos. Today it is still possible to see some of these wonderful birds, but every meeting is also tinged with regret. For Hawaii, as well as presenting a wondrous cradle of evolution, has also become a desperate battleground where species are fighting for their very existence.

Nowhere is the war fought more fiercely than in the highlands of Kaua’i, the westernmost of the main islands. This is one of the wettest places in the world; indeed, Mount Waialeale experiences rain for 360 days a year, adding up to an annual total of 10 m. On the west side of this island lies Koke’e National Park and the adjacent Alaka’i Wilderness Area, a large expanse of alpine forest that still retains high proportion of its original flora and provides a last refuge for much of the island’s birdlife. It is a remote and lonely place, with long trails that go through thick forest and traverse ravines; there is also the so-called Alaka’i Swamp, a bog with spongy ground and almost impenetrable vegetation. It resembles, and indeed is, something of a last frontier.

The dedicated birder will be able to find up to six native bird species here, while the fanatic may find two more with a great deal of effort. By taking the popular Pihea Ridge trail any visitor should soon come across several species of ‘dreps’, the affectionate term used by local birders for Hawaiian honeycreepers, the Drepanididae. The commonest are the Apapane, the Kaua’i Amakihi, the Anianiau and the Akekee. The Apapane is a delightful nectarivorous tit-sized songbird, a bright red species with a long, sharp bill. It can be seen almost everywhere, often guzzling its favourite red o’hia blooms (this eucalypt beinvg one of the dominant plants of the forest). This is the most abundant of all the dreps, being found on most of the main islands. The Amakihi, by contrast, is a small, yellow-and-green species with a short, decurved bill; it gleans insects from branches and trunks, as well as also taking some nectar. This is another fairly common species, the only one that also occurs in the lower parts of the island. The Anianiau is similar to the Amakihi but much brighter yellow all over, and with a very narrow bill that is used to probe for nectar into the o’hia blooms; in common with the other nectar-feeding dreps it has a brush-like tongue that is also effective for catching tiny insects. Besides foraging in o’hia trees, Anianiaus also nest in them, as does the Akekee, yet another small yellowish bird which, in contrast to the others, appears to shun nectar in favour of an invertebrate diet, and has a comparatively short bill.

Another common bird here is the Elepaio, yellowish-brown with two pale wing-bars, another native and a member of the monarch family. Less common, but still likely to be seen, is everybody’s favourite drep, the stunning Iiwi. This gorgeous bird is brilliant red in colour, with black wings and white spots on the inner secondaries; its bill is sharply decurved, betraying its nectar-feeding habit. Although common on some other islands, this species appears to be declining here.

By being a bit more adventurous, the birder can also seek out two great rarities. These are the Puaiohi, a rather dull-plumaged thrush, mainly found in the swamp area, and the Akikiki, a drep that is the Hawaiian equivalent of a nuthatch, finding its invertebrate food by foraging unobtrusively along trunks. This sharp-billed species, grey-brown above and whitish below, appears to be in severe decline and is now very difficult to find.

Soon the Akikiki will probably be impossible to find. Its decline seems to be remorseless and its range is contracting towards the east of the site, which has ominous parallels with several other species from this part of Kaua’i that have now become extinct – unless somewhere, somehow, deep in this inhospitable terrain, they still cling on to survival. The sad fact is that this very site, where nowadays visitors can be stunned by the sight of the Iiwi and Apapane, has lost more birds to extinction in the last 25 years than anywhere else on earth. The Greater Akioloa was last seen in 1967 and was the forerunner of several species lost in quick succession: the last confirmed Kauai Oo, a male, was seen in 1985; the last Ou in 1989; the last Kamao in 1993 and the last [Kauai] Nukupuu in 1998. Almost all of them were last seen around the area of the Alaka’i Swamp.

The reasons for this sorry state of affairs include most of the usual blights on restricted island species. Deforestation and development reduce the amount of available habitat. Introduced plants compromise the native vegetation. Introduced animals – in particular here, pigs – further denude and disrupt the habitat. Introduced birds (there are more species of them in Hawaii than anywhere else on earth, and they reach even these montane forests) out-compete the natives for food. Introduced predators, such as rats, attack nests.

In Hawaii, however, there are other threats, too, which are even more insidious. In the archipelago as a rule, the main wave of local bird extinctions began with the introduction of mosquitoes. Carried by introduced birds, avian malaria and pox killed thousands of dreps and other native birds, and at a stroke confined them all to regions above 1,219 m, where mosquitoes could not reach. At the same time, introduced ants and wasps have predated young birds or competed for nectar; the local birds have had no defence against these alien creatures.

Worryingly, there are signs that mosquitoes are beginning to reach the higher altitudes of Kaua’i. If they do, it is difficult to see how some of the native birds can survive. If you would like to see some of these special birds, you should probably visit soon.

The colourful I’iwi is a nectar-feeder.

Parts of Hawaii are among the wettest places on earth.

The Kaua’i Amakihi is mainly insectivorous; it forages by gleaning foliage.

An Apapane guzzles from its favourite O’hia blooms.