Ecuador

Galapagos Islands

Information

SITE RANK

5

HABITAT Volcanic islands, with cliffs, beaches, forest and semi-desert.

KEY SPECIES ‘Darwin’s’ finches including Woodpecker Finch, mockingbirds, Galapagos Penguin, Flightless Cormorant, Waved Albatross, Swallow-tailed and Lava Gulls and other seabirds.

TIME OF YEAR All year, seabird colonies busiest between February-September.

On the whole the famed Darwin’s finches are disappointing as a tourist attraction – this is a Medium Ground Finch, which occurs only on Floreana.

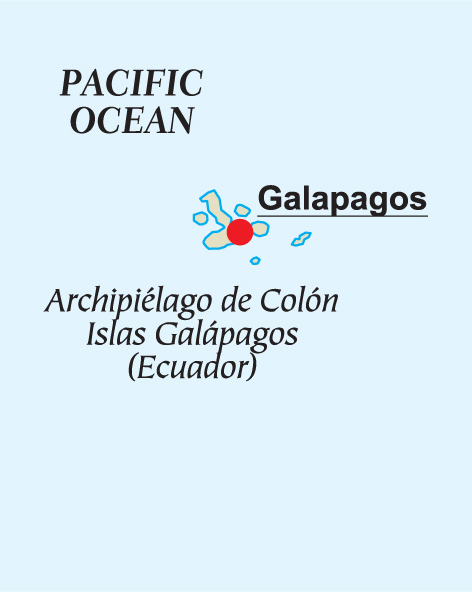

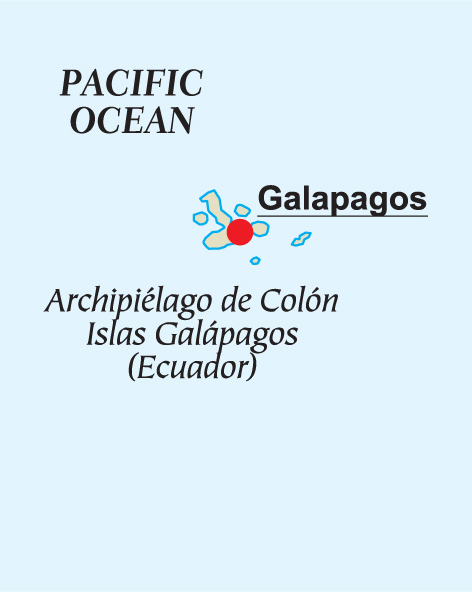

These islands, which lie in the Pacific Ocean 1,000 km west of Ecuador, on the Equator, are among the most famous destinations in the world for watching wildlife. Their fame is partly aesthetic and partly scientific. In the first place they are remote, starkly beautiful and relatively unspoilt, with many islands, even quite large ones such as Española, still uninhabited by people. Their wildlife is tame, abundant and often spectacular. Secondly, these islands were visited in 1835 by the pioneering English naturalist Charles Darwin, and in the course of making observations here, most famously on the native finches, he was able to ruminate on what would become his theory of evolution, one of the great landmarks of modern science.

Following Darwin’s footsteps is a thrill that many thousands of visitors cannot resist and, whether or not the islands are over-hyped (for example, Darwin actually made very little reference to the archipelago’s finches in his writings, and their importance to his thinking is disputed) scarcely matters to those that come here for the memorable sights and sounds. The main point is that much of what occurs on the Galapagos is unique: the Giant Tortoises, the Marine Iguanas and, of course, the birds, of which there about thirty endemic species. What you can see here, often at close quarters, cannot be seen anywhere else.

Oddly enough, those celebrated finches, nowadays often collectively known as Darwin’s finches, are pretty dull to look at and extremely difficult to identify, so to a casual visitor they can prove to be pretty disappointing. They are basically small, dark (to blend in with the volcanic soil) and streaky, with the females browner than the males. Where the various species differ is primarily in their bill shape, which is closely correlated to their feeding behaviour and ultimately the ecology of the islands. However, don’t expect these distinctions to be obvious in the field, because often they are not: the bill of the Large Cactus Finch is not very different from that of a Large Ground Finch, except in diagrams in textbooks.

However subtle, the differences between the finches are truly fascinating. Marvel, for example, at how the bill of the Large Ground Finch is so hefty that this bird can tackle much larger seeds than the Medium Ground Finch or the Small Ground Finch. The distinction, furthermore, between the two arboreal insectivorous tree finches is also intricate: the Large Tree Finch has a thick, hooked bill for tearing bark, whereas the bill of the Small Tree Finch is narrower and used mainly for plucking insects from the surface. One species you will have no trouble at all in recognizing is the Warbler Finch, because its bill is much thinner and is used for probing into cracks and among leaves. It has, however, recently been split into two species, the Olive Warbler Finch and the Dusky Warbler Finch, presumably to keep birders on their toes.

Some of the finches exhibit distinctly odd behaviour. For example, the Woodpecker Finch is a tool-user which plucks twigs from herbaceous bushes (or the spines off prickly pear cacti) and uses them to pry termites and insect larvae from bark or wood cavities. The behaviour of the Sharp-beaked Ground Finch is even more strange; on the island of Tower, where there are huge numbers of breeding seabirds, it will casually approach the sitting Red-footed Boobies and peck at the base of their feathers; that will be enough to draw blood, which the finch drinks!

It seems that unusual forms of behaviour are rather commonplace here. The Wedge-rumped Storm Petrel, for example, is the only member of its family to occupy its breeding areas during daylight hours rather than during the night. This has presumably arisen in the relative absence of predators, since there are no skuas here and the gulls, on the whole, are well behaved; the squid-eating Swallow-tailed Gull, indeed, is virtually nocturnal as a feeder itself, unlike most other gulls. The storm petrels, however, suffer from predation by Short-eared Owls. Another behavioural quirk has recently been discovered in the Galapagos Hawk. Despite being large and broad-winged, this raptor is apparently highly adept at hunting small landbirds, rather than the larger prey or carrion you might expect.

Aside from the finches, the mockingbirds are perhaps the most sought-after of the islands’ inhabitants, at least by birders. The Galapagos Mockingbird is widespread, but the other species all occupy tiny ranges. The San Cristóbal and Hood (Española) Mockingbirds occupy their respective islands, while the Floreana Mockingbird now occurs on only two small islets off its namesake, and has a world population of no more than 260 individuals. In common with many Galapagos animals, these mockingbirds have a habit of being inquisitive and utterly fearless, and some apparently cannot resist the urge to peck at visitors’ shoelaces!

Although the landbirds are undoubtedly fascinating, the seabirds of the Galapagos provide much of the spectacular viewing. There are huge colonies of Red-footed and Blue-footed Boobies, together with smaller numbers of both Magnificent and Great Frigatebirds, dotted throughout the archipelago. One of the islands’ most impressive spectacles is the colony of Waved Albatrosses on Española, which stands at about 18,000 pairs. These birds can often be watched performing their comical sky-pointing displays. Two very rare endemic species are also found here. The world’s northernmost penguin, the Galapagos Penguin, occurs in small numbers on some of the western and central islands, while the Flightless Cormorant is found only on Isabela and Fernandina – it is the only member of its family to have lost the power of flight. The world populations of these vulnerable species are estimated at 1,200 and 900 respectively.

Of course, any species confined to a single island or island group is more likely than most to be vulnerable to extinction, and the birds of the Galapagos are no exception. In recent years, both the penguin and the cormorant have been affected by fluctuations in the El Niño current. One species of finch, the Mangrove Finch, has been decreasing for unknown reasons, and its population now numbers a shaky 100 individuals in just three sites on Isabela. In the 1990s, visiting boats are thought to have brought in parasitic flies that are now found in a high proportion of finch nests, reducing breeding success. Despite the impression that these islands give of being far distant and locked away from modern life, it appears that even they are not immune to threats from the outside world.

Typical Galapagos habitat – the islands are volcanic and many of them appear bleak and dry.

The rare Flightless Cormorant, with a vulnerable world population of only 900 individuals, is found only on two islands.

Waved Albatrosses is a Galapagos speciality – the species breeds on Española.

One of two gulls endemic to the Galapagos (the other is the Lava Gull), the elegant Swallow-tailed Gull feeds almost exclusively by night.