Sometimes when a civilization dies, it doesn’t happen in a cataclysm. The cities survive—after a fashion. So, too, do the people. The end itself is anticlimactic. Fire comes, as it invariably does, but finds little to consume. A spiritual destruction has preceded it, leaving behind little of value—diminished art, narrowing intellectual interests, a rotting infrastructure long neglected by engineers. The survivors, too weary to put up an apocalyptic struggle, offer little resistance. Some welcome the end. Others live in extravagant denial.

There had been a time, back in the second century, when it must have seemed like a good idea to surround the Empire with walls, so that the people, relieved of insecurity, could concentrate on music, art, philosophy, and fine buildings. Hadrian, the architect of the policy, loved all those things. But the Greek-loving emperor had picked and chosen from the lessons of history. He was always more enamored with Athens than with Sparta; otherwise, he might have heeded the ancient Spartan warnings about walls. He might have worried that the walls would change the people they were protecting.

Aristides had also missed the warning signs. When the orator celebrated the peaceful, prosperous conditions that prevailed behind Hadrian’s walls, he embraced the demise of the citizen-soldier. Rome, he declared, would never stoop to asking its own citizens to fight. He never considered the possibility that a people who’d forgotten what war was like would be utterly unprepared for it when it came.

The later Roman emperors, who so frequently endured the verbose, unctuous flattery of professional sycophants like Aristides, didn’t have the luxury of being oblivious. They were increasingly tasked with defending a population that could not defend itself. Frequently they came to doubt the toughness even of the soldiers themselves. They tried to stiffen up the troops by denying them the luxuries that had become the raison d’être of Roman life—do as I say, not as I do—but this rarely accomplished much. Eventually, the emperors doubled down on the Hadrianic strategies that had briefly succeeded in the second century. They built more border walls and more city walls, while recruiting ever more soldiers from the ranks of the unwalled warrior societies beyond the borders. None of this would have mattered had Rome’s enemies been the sort who believed wars were fought between states and that civilian populations should be spared from violence. But the warriors from the unwalled regions didn’t even recognize the concept of civilians. In the civilized Romans, living behind walls, they saw only wealthy weaklings—the sort of people who would give up everything they had just to be left alone.

By the late fourth century, the Roman Empire, civilization’s longtime bulwark against the forces of the forests and steppes, was a spent force. The vast energies that had once propelled classical civilization from the shores of the Mediterranean to the edge of the Atlantic were exhausted. From Greece to Britain every monument, every achievement, had been founded on the essential belief that what one built would not soon be destroyed, and that cities were more than mere castles in the sand. Now it seemed as if nothing could withstand the tide. If there was a way to resist it, the people didn’t remember how.

* * *

In AD 376, a large body of Goths arrived at the Danube River, pleading to be allowed into the Empire as refugees. These were the same barbarians whose forefathers had slain an emperor, sacked Athens and Ephesus, and taunted the walled-in Romans for living like birds in a cage. They had recently received their comeuppance from the Huns and Alans—two nations then widely identified with Gog and Magog. The Goths had no answer to the tactics of the steppe men, and after a desultory attempt at building their own great wall, they decided that perhaps the Empire knew a thing or two about security after all.

The Romans would have been amply justified in turning away their old foes. The Goths certainly had it coming, and schadenfreude, after all, is a dish best served while watching one’s archenemies scramble haplessly to construct a proper wall. But thousands of men, socialized from birth to be warriors, were seeking entrance into an Empire whose greatest problem remained how to recruit soldiers from a walled and unwarlike populace, and from a certain perspective the arrival of the Goths could be viewed as an opportunity. A bold and unfortunate idea presented itself. The Romans, eyeing the crowd of barbarians as just so many potential recruits, agreed to the Goths’ request. Roman officers supplied vessels to transfer the Goths into the Empire, ferrying them across the Danube on boats, rafts, and canoes for several days and nights. At the time, it must have seemed like a clever and perhaps even generous move—good for both the Goths and the Romans—but this Gothic Dunkirk soon turned sour. For in the memorable phrase of the Roman historian Ammianus, Rome had just admitted its own ruin.

The refugees, unhappy in their new conditions, had hardly entered the Empire before they turned on their hosts, ambushed a Roman garrison, and began raiding cities and villas. According to Ammianus, the land was set on fire. Women watched while their husbands were murdered. The Goths tore babies from their mothers’ breasts and dragged children over the dead bodies of their parents. They drew ever closer to Constantinople, the city that had only recently emerged as one of the dual capitals of a state that in those days typically had two emperors. The refugees had become invaders, and this at last roused the attentions of the eastern emperor, Valens.

Valens was an unmemorable leader, the latest of dozens who spent their careers in ceaseless, desultory combat against barbarians. He briefly earned praise for repairing the border walls and ending the practice of paying out vast tribute to barbarians. But posterity recalls him for another reason: the horrific defeat of his army by the Goths.

The Battle of Adrianople (AD 378) figures prominently in nearly every account of the fall of the Roman Empire. In the centuries leading up to the great defeat, the emperors had all but extinguished the warrior element within their own subjects and, in their search for hired killers, had badly miscalculated in allowing the Goths to immigrate. When night fell over that terrible battle in which Gothic axmen hacked through the ranks of the Roman soldiers, the survivors scattered or fled to the protection of the nearest walls. There, the townspeople of Adrianople—in Latin, Hadrianopolis, fittingly “the city of Hadrian”—closed the gates before their protectors could even get inside. The next day, when the Goths attacked the city, searching for an alleged cache of imperial treasure, the cornered survivors fought with their backs to the walls. When the Goths finally relented from their attacks, the townspeople rolled huge boulders behind the gates.

Adrianople lay just one hundred miles west of Constantinople, which was now vulnerable after the defeat of the emperor’s troops. When the barbarians marched on the great eastern capital, it had no Roman troops left to defend it. Only a band of Saracen warriors that the Empire had imported from the deserts of Arabia rallied to the city’s defense. In the fields outside Constantinople, a bizarre spectacle ensued. Barbarian fought barbarian, one band a Rome ally, the other its sworn enemy, neither side gaining the upper hand until a lone Saracen, wearing only a loincloth, raced into the meat of the Gothic host, stabbed a soldier, and sucked the blood from his throat, terrifying even the Goths. This is what the battle for civilization had become: Constantinople—the “new Rome”—saved by the most feral feat of barbarism, while the citizens watched from the walls.

Had the Spartans gotten it right all along? Had the Romans authored their own demise by constructing walls that turned their men into hapless softies? The brash future bishop Synesius, who arrived in Constantinople to deliver his opinions some twenty years after Adrianople, certainly thought so. For Synesius, who fancied himself of Spartan descent, the triumph of the civilian element in Roman society had gone too far. He insisted that the Empire had pampered its citizens by importing barbarian mercenaries to defend the state while excusing native Romans from service. In the course of a long oration in which he repeatedly decried the effects of luxuries on the martial spirit, Synesius naturally came around to the topic of walls. After declaring that the early Romans had never walled their city—a patently false remark, as everyone in his audience, being familiar with the myth of Romulus, very well knew—Synesius prescribed nothing less than the complete dismantling of the civilian society so praised by Aristides. Rome, he said, should be drafting its farmers, philosophers, craftsmen, salesmen, even the ne’er-do-wells who loitered incessantly around the theater. Until then, the only real men in the Empire were the barbarians. Native Roman men had been reduced to playing the woman’s part, and the barbarians would soon take over.

* * *

Synesius’s prescription never stood any realistic chance of adoption. It went against every impulse that civilized people had shown for at least three thousand years. Not just the Romans, but, before them, the Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Chinese, and essentially every civilized nation in Europe or Asia had concluded it was better to allow walls and foreigners to do their fighting for them rather than devote their own lives to constant preparation for war. They opted for baths, theaters, games, and schools over tests of endurance, beatings, periods of deliberate deprivation, and other toughening exercises. It all seems obvious in retrospect, but Synesius couldn’t quite see it.

What Synesius could envision—the demise of Rome—played out exactly as he had expected. A new breed of ambitious foreigners arose to exploit the weaknesses that Synesius described. Bred from the Empire’s desperate gambit of hiring barbarian mercenaries to defend unarmed Romans, they were sophisticated enough to play at imperial politics while at the same time still savvy to the desires of their violent, crude men. They straddled two worlds and very nearly mastered both. The late Roman world teemed with such creatures. Gainas, a Goth, briefly took control of Constantinople. Another Goth, Alaric, shook the world.

In the autumn of 408, Alaric besieged Rome for the first time. The city’s vast Aurelian walls were enough to keep out the barbarians, but they simultaneously imprisoned the hapless civilian populace. Corpses filled the streets of the starving capital. After a while, the Romans tried to bluff Alaric, sending envoys to inform him that they had taken up arms and were prepared to fight. Alaric only laughed at the threat. His famous reply—“Thick grass is more easily cut than thin”—is a bit of a puzzler, perhaps because the cutting of grass was just another civilian activity about which the warrior Goths apparently knew nothing. But clearly, any notion that a community of poets and politicians could intimidate the Goths, most of whom had never spent a day behind walls and had lived all their lives in camps, seemed ludicrous to Alaric. He demanded all the gold and silver in the city.

“What will be left to us?” the Romans asked.

“Your lives,” came Alaric’s reply. He refused to allow any Roman to leave the city for food until they began melting statues to provide him with gold.

The Romans temporarily satisfied Alaric’s demands, but he returned again the next year, and then again the year after that. Finally, in August 410, when Alaric’s negotiations with the emperor were interrupted by a surprise attack—made, naturally, by barbarians in the service of Rome—the Goth led his troops into Rome and pillaged the Eternal City.

The aura of Rome failed to endow the city with any special protection. Women were raped, and corpses left unburied. In some quarters, the burned shells of buildings stood unrepaired for decades. Refugees streamed out of the city and took boats to distant cities such as Jerusalem, where Saint Jerome helped take them in. Leaving behind the smoking capital, Alaric and his Goths passed into southern Italy, where an observer writing more than a century later could still see the rubble of cities left in his wake. Rome had been brought low by a band of barbarians, and, worse still, by barbarians who were supposed to be defending the Empire. “The brightest light of the whole world is extinguished,” wrote Saint Jerome. “. . . The whole world has died with one city.”

* * *

And yet the Roman Empire did survive the brutal sack of its capital. The emperors continued to sit in Ravenna or Milan or Rome and Constantinople for some decades, weaving their little webs, cutting deals with barbarians, imagining they still ruled the world. They possessed few options beyond hiring barbarians to defend their provinces, and that was no real option at all. The barbarians, by and large, did as they pleased, accepting the emperor’s expensive bribes, then taking what they wanted from the cities they held hostage.

The century after the sack of Rome sorely tested the late-Roman strategy of using city walls as a last-ditch defense. As rural folk fled to the walled cities, agriculture was neglected, causing a famine so severe that many were driven to cannibalism. One wretched woman was stoned to death for eating all four of her children.

The old border walls had become obsolete. They required the sort of support a fading Empire could no longer afford. Many of the Roman troops formerly stationed on the frontiers gave up and left when they realized that no pay was forthcoming. In the region of Austria, a single garrison of border guards held out in isolation. Desperate for money, the troops sent some men to Italy for pay, but the expedition was ambushed by barbarians. The bodies of the slain washed ashore by a river. In Britain, Roman troops finally abandoned Hadrian’s Wall, allowing the area to return to forest. A hundred years later, a Greek author recalled the Wall only as a mythic barrier erected by “men of old.” Beyond the Wall, he wrote, lay an uninhabitable zone where the poisonous air would suffocate a man if the countless snakes hadn’t gotten him first. He was referring to Scotland.

A British contemporary of the Greek author’s also tried to make sense of the demise of Roman Britain. He reckoned it had happened something like this: a defenseless Britain, denuded of its imperial troops, had petitioned Rome for aid. The Romans subsequently sent an army and drove off the enemy, but then departed, leaving instructions that the British should construct a wall against future invasions. The provincials built this wall out of turf, but it did little good, as the enemy soon swarmed over it, slaughtering everyone they encountered. For a second time, the Romans dispatched an army to save the Britons, but this time their advice was sterner: stop being such lazy cowards, take some weapons, and learn to fight your own battles—oh, and build a better wall. Left to their own devices yet again, the provincials obediently constructed a towering wall of stone. Unfortunately, they were unable to defend it. The enemy dragged them off the wall with barbed weapons and dashed them to the ground.

Our British author was wrong in nearly every detail. He is aware of both Hadrian’s Wall and the later Antonine Wall, which was made of turf, but he has confused their histories and reversed the timing of them. Only in his general theme has he gotten it right: the Romans of the provinces, long accustomed to peace inside their walled world, no longer stood a chance on their own.

Synesius had seen this coming all along. Just a few years after delivering his ranting jeremiad in Constantinople, he experienced the mixed fortune of seeing his dire prophecies borne out. In North Africa, where his brash leadership had been awarded with a bishopric, his home city of Ptolemais came under siege by barbarians. The meekness of the townspeople confirmed Synesius’s darkest fears. Far from rallying in defense of their property and families, the Romans of North Africa had merely huddled behind their walls, praying for the intervention of the army and complaining when it didn’t come. The barbarians seized women as slaves, took away livestock, killed any men they found outside, and left the rest imprisoned behind their own ramparts.

For Synesius, this was all too much. The self-proclaimed descendant of Spartans and apostle of self-help chafed for action. Against the advice of his own brother, the two-fisted bishop began organizing his fellow citizens. He oversaw the manufacture of weapons, including even a type of artillery for hurling heavy stones from the walls. What he could not manufacture, he purchased from traders. Although hindered significantly by the region’s lack of iron production, Synesius amassed a patchwork arsenal: three hundred lances and single-edged swords, along with some hatchets and clubs. For soldiers, he attracted volunteers from among the young men. Some he placed as guards around the wells and rivers. The rest he led out on morning and evening patrols.

The raiders, for their part, were bemused by the philosopher’s efforts. Having encountered some of Synesius’s scouts, they sent word to the city to prepare for battle. They were curious, they admitted, as to what sort of sedentary people could possibly have the audacity to go out and fight warlike nomads such as themselves.

Synesius’s militia succeeded only temporarily, holding back the deluge for a short while until a Roman army finally arrived to scatter the nomads. Fifteen years later, the North Africans would receive no help from Rome when the Vandals arrived in 429. The new invaders were far more destructive than their predecessors. The Vandals left large piles of bodies outside town walls to suffocate any holdouts with the stench of putrefaction. Using Africa as a base, the Vandals launched annual spring raids on Italy and Sicily, where they razed some cities and enslaved the populations of others. Bishops debated whether Matthew 10:23 (“When you are persecuted in one place, flee to another”) licensed them to abandon their congregations. Talk of Gog and Magog was in the air. No civilian resistance materialized, however. In Roman Carthage, the townspeople ignored the calamities befalling the cities all around them and continued to attend games and circuses. More than one author observed with disgust that the oblivious Carthaginians went to the circus on the very day the city fell to the Vandals in 439. They’d put all their faith in the walls.

Occasionally, as the Empire collapsed around them, some Roman in this or that province would rally a few men, Synesius-style, to take up arms against the barbarians, but such heroics were rare. As a measure of how helpless and dependent the inhabitants of the walled cities had become, an edict issued by Valentinian III (r. 425–55) makes for a rather poignant memorial: it reminds the people of their obligation to defend their city walls. How could this not have gone without saying?

In the meanwhile, the countryside, suffering as long-term battlegrounds so often do, belatedly followed the lead of the cities. The great villas where aristocrats had long lived in pampered luxury, swimming, reading, exchanging chatty letters, and commissioning extravagant art, were gradually abandoned in favor of more secure hill forts. The transformation of the western Roman Empire was soon all but complete, its abandoned border walls gradually replaced by hundreds of smaller walls, most of them slapdash timber palisades.

Aristides wouldn’t have recognized the place.

For some time after the fall of Rome, new earthen walls crisscrossed much of Europe, even when no great empires were left to build them. In England, the numbers of Devil’s Dykes, Devil’s Ditches, and Devil’s Banks is exceeded only by the number of Grim’s Dykes, Grim’s Ditches, and Grim’s Banks. Denmark is similarly replete with medieval earthworks. Even the Slavs, themselves only recently arrived from the steppe, constructed long barriers against their former homeland. The long walls of the Dark Ages are impossibly anonymous, and the tendency to reuse older Roman or even Iron Age defenses only muddles their histories more. None of these barriers played more than a passing role in providing local or national security.

The ancient model of empire, defended by walls and mercenaries, survived only in southeastern Europe, where the eastern half of the Roman Empire did not fall in the later fifth century. Benefiting from a securely walled capital, it carried the name of Rome for another thousand years, although we have retroactively dubbed it the “Byzantine” Empire.

The eastern emperors abandoned the Hadrianic strategy of placing a hard shell around the provinces in the early fifth century. From that point on, all efforts were concentrated on the defense of Constantinople. The construction of new walls for the capital gained particular urgency after the sack of Rome. Theodosius II receives credit for the project, although he wasn’t yet ten years old when it commenced (he’d been made co-emperor as an infant, so in theory he wasn’t without experience). Over time, he supplied Constantinople with fortifications worthy of Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon. Three progressively taller walls surrounded the city. The innermost wall stood an imposing twelve meters high and bristled with towers. The outermost wall overlooked a wide moat. Inside, Theodosius and his successors secured the water supply with wells, reservoirs, and spectacular underground cisterns. They also ensured that Constantinople wouldn’t fall victim to the helplessness of its populace. Reigning over a city obsessively devoted to spectator sports, they established early on that every citizen had a responsibility to defend the walls when the city came under assault.

The decision to prioritize the walls of Constantinople over the old imperial border walls had immediate consequences. In the agonizing period from 422 to 502, when the western Roman Empire was crumbling, barbarians ravaged the region north of Constantinople eight times, an average of once every decade. There wasn’t much that could be done about the invasions in those days. By the time an aging Anastasius (r. 491–518) came to power in the late fifth century, it was clear he’d been dealt a losing hand, although he put a brave face on it. To the kings of the Franks, Ostrogoths, and Vandals, who had taken control of France, Italy, and North Africa, respectively, he granted impressive-sounding Roman titles and “special friendships,” as if he were still their emperor. The barbarians, so far as we can tell, thanked him for his kindness, patted his ambassadors on the head, and carried on as if he were some distant Constantinopolitan relic of a bygone era—which, in fact, he was. Back in the capital, Anastasius drew up plans for a new border wall closer to home.

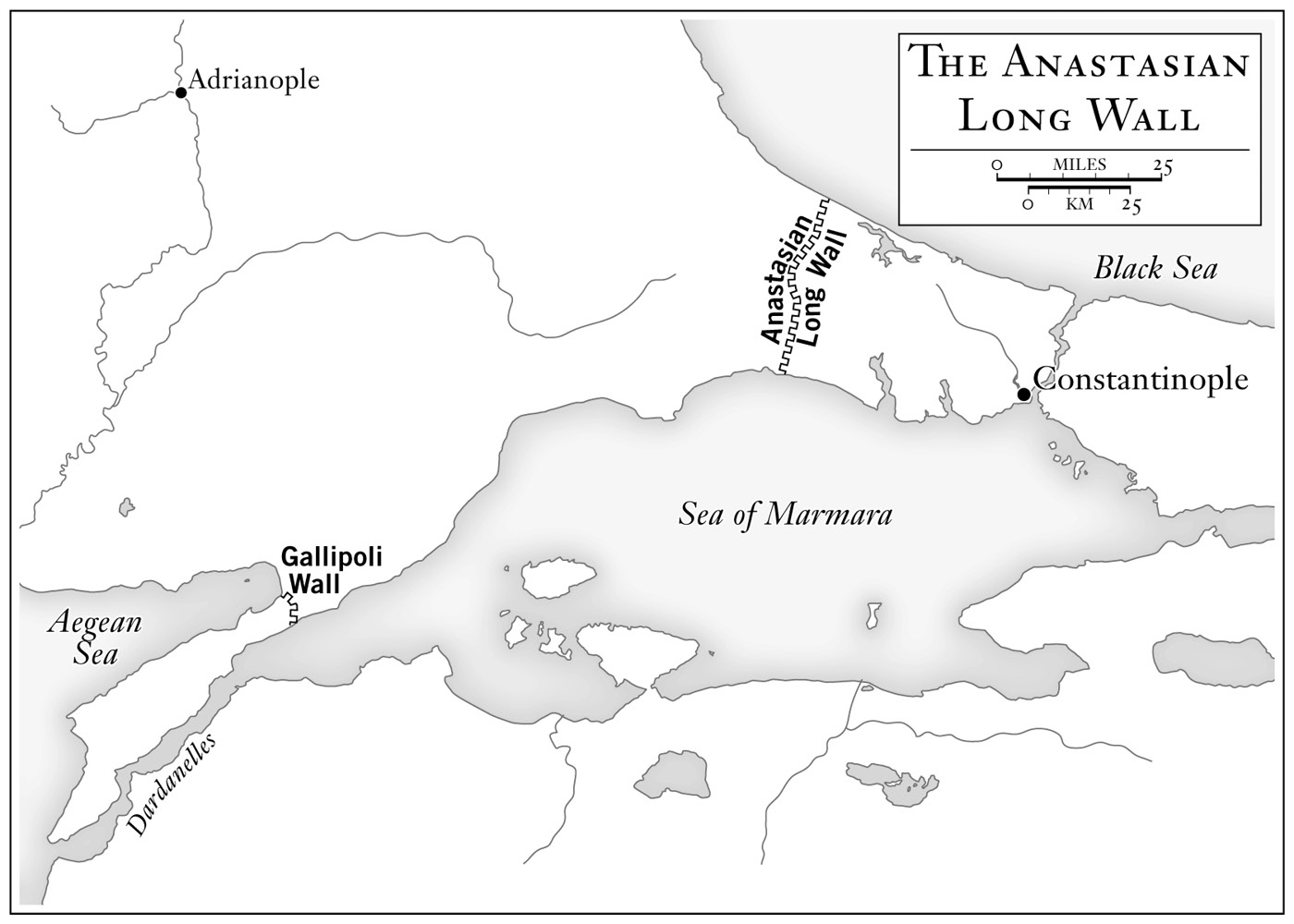

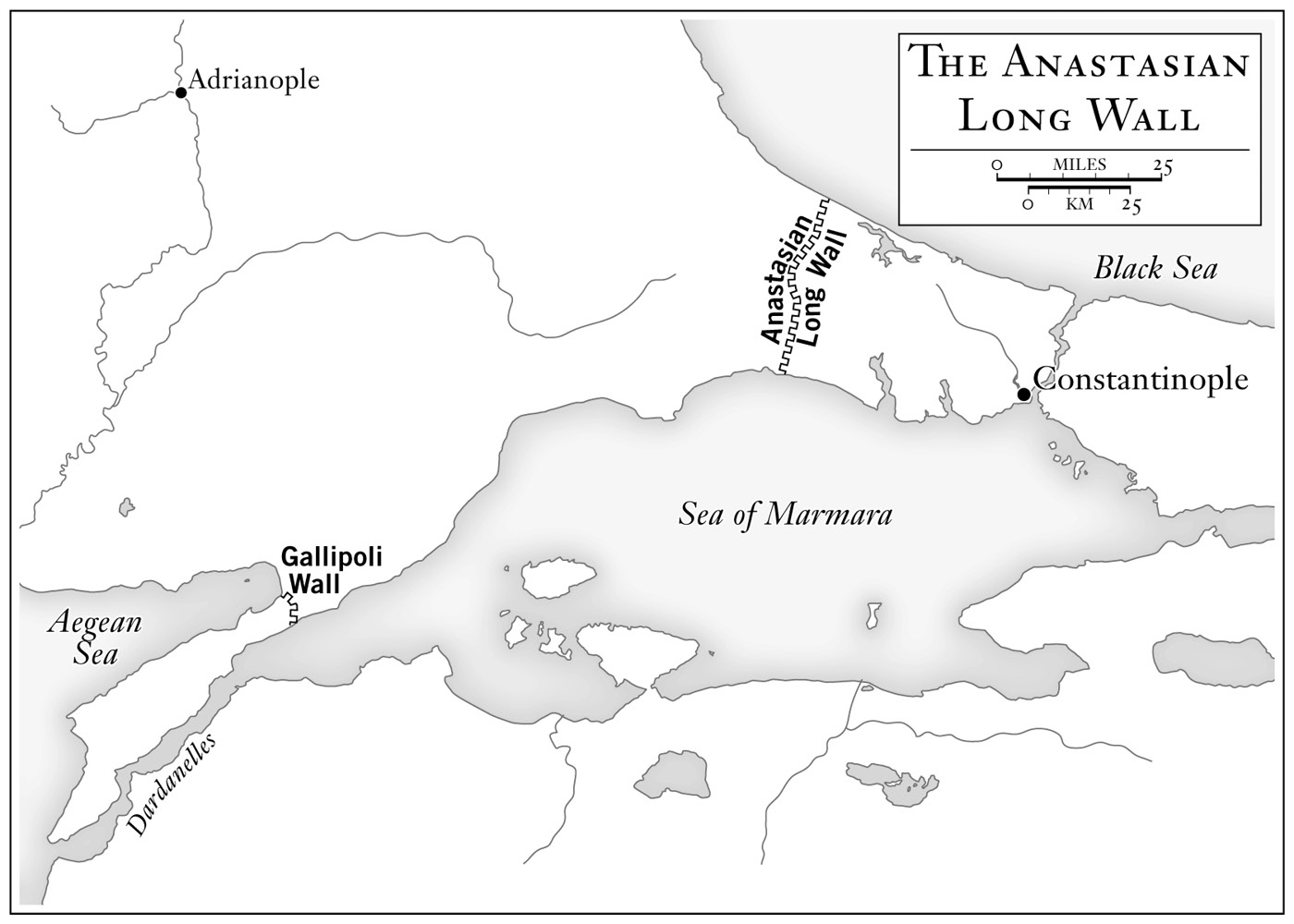

The Anastasian Long Wall ran well south of previous barriers, stretching approximately forty miles from the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara. Anastasius thus despaired of protecting not just Ovid’s former home of Tomis, but the earlier lines once created by the misnamed Trajan’s Walls. Most of Roman Thrace (primarily modern Bulgaria) now lay well north of the new fortifications. This was all terrible for the inhabitants of Byzantium’s most endangered province, but the wall’s location did make sense, at least from the emperor’s point of view: it was close enough to the capital to be defended by residents of the city. On numerous occasions, Constantinopolitan sports fans were called away from their games to defend the Anastasian Long Wall. The wall proved its defensive value repeatedly, stopping the Avars and Slavs six times in one ten-year period.

It was all a game effort, but Anastasius was no Hadrian. Already elderly by the time he took the throne, he simply didn’t have the energy to fortify the entire Empire and probably never gave serious thought to the notion. Anastasius had reduced his ambitions to suit his reduced circumstances. He was putting Byzantium on a path toward the bunker, and, in fact, that would be the Empire’s ultimate destination.

* * *

A decade after Anastasius’s death, the Empire would have as its sovereign a different sort of leader, a prolific builder of walls, who would make one final attempt to rescue the Empire from oblivion. For a while, it seemed as if Byzantium would have its Hadrian.

In the various sources surviving from his reign, Emperor Justinian comes down to us in two versions: the pious, amiable fellow who gloriously rebuilt a broken Empire and the duplicitous tyrant who turned it into a kind of hell. The truth, as the saying goes, undoubtedly lies somewhere in the middle—if by middle we mean primarily the latter account. Both the positive and the negative accounts agree that Justinian found it difficult to leave any aspect of life unsupervised. His subjects knew him as the “emperor who never sleeps,” tireless in his oversight, and within just five years, his heavy-handed new laws and even heavier taxes had made him so universally loathed that he had seemingly done the impossible and united every sports hooligan in Constantinople in opposition to his reign.

The riotous union of rival chariot-racing factions in AD 532 shook the palace so thoroughly that Justinian nearly abdicated, but the empress, Theodora, was made of somewhat sterner stuff. She declared that she would rather die than not be empress. Theodora is herself notorious in the annals of the Empire. Justinian’s court historian, unleashing some pent-up venom in a scandalous tell-all, insisted that the empress, in her former career as a prostitute, had routinely worn out ten clients in a single evening before wearing out their thirty servants for her own amusement. She’s also reported to have performed a rather infamous stage act in which she sprinkled seeds on her private parts, then allowed geese to pick them out. As empress, she frequently played bad cop to Justinian’s good. In this capacity, she spared no cruelty—being the sort who would accuse a man of homosexuality and then have him tossed into a dungeon and tortured.

The imperial couple’s innate tendencies to despotism would soon be channeled in a familiar direction. In the 540s, various barbarians arrived from the steppe and fell upon the Byzantine Empire. Here and there, they encountered old walls. On the Gallipoli peninsula, they took to the surf to slip around and attack the wall’s defenders from both sides. Similarly, at Thermopylae, the barbarians skirted the old wall that had saved Greece from invasion just two decades earlier. All of Greece north of the Peloponnesus was overrun. The invaders massacred any Romans they captured. Some they impaled, others they tied to stakes and beat to death, and still others they burned to death in their huts. Many country dwellers fled to the walled cities, which quickly filled up with slapdash stone-and-clay houses. Others fled into mountains and forests, their country reduced to a “Scythian desert.” When the invaders plundered even the suburbs of Constantinople, Justinian barricaded himself in the palace. The invaders returned home flush with booty and over one hundred thousand prisoners.

The experience of being trapped in the palace was quite enough for Justinian. Like a host of other monarchs before him, he calculated that he had more workers than warriors and then put them to work. The emperor had always fancied himself a great builder. Earlier in his reign, he’d constructed lavish churches and elegant cities; even his cisterns resembled cathedrals. Upon completing the reconstruction of the great domed church, Hagia Sophia, he boasted that he had outdone Solomon. However, the extravagant quality of Justinian’s early work vanished in his later efforts. Now, as he sought to outdo not Solomon but Hadrian, he repented of his earlier emphasis on aesthetics and concentrated on stouter, more formidable things.

Justinian erected fortifications across southeastern Europe. He rebuilt cities that had been destroyed, constructed new walled cities in strategic locations, established new forts along the rivers, and even fortified rural farmsteads. At the storied pass of Thermopylae, he erected new walls not only at the traditional gates where the three hundred Spartans had once fought the Persians, but at every nearby route through the mountains as well. He restored an isthmus wall of the Kassandra peninsula in northern Greece and even provided long walls to a community of Christian Goths in the Crimea. At Corinth, he continued a tradition dating back to Mycenaean times when he rebuilt the old wall that had formerly blocked off the Peloponnesus. Meanwhile, he bolstered the Anastasian Long Wall above Constantinople and, at Gallipoli, demolished the eroded ruins of an old wall and erected in its place a far more formidable structure, vastly higher, with a roof over the fighting platform and with bastions extending well into the water on either end. Justinian’s building program was so vast that the task of describing it finally overwhelmed even Procopius, his generally indefatigable court historian. After dutifully writing a few volumes on the emperor’s fortifications, the muse deserted Procopius altogether, and he could do no better than list the new works. As it turned out, he wasn’t terribly impressed by all the frantic wall building anyway; he was more interested in dishing on the empress’s sexual history.

Justinian’s walls had not come cheap, and as Procopius reveals in his Secret History, the cost of guarding them all but drained the Byzantine treasury. When Justinian’s notorious subordinate, Alexander the Scissors, eliminated the venerable tradition of having local farmers man the famous wall at Thermopylae and replaced them with two thousand regular troops, the expense nearly bankrupted Greece. Making matters worse, the emperor had started paying his longtime enemies, the Persians, to construct walls. In 562, Justinian purchased from the Persians an expensive peace treaty. The agreement stipulated that Persia should never allow Huns or Alans to cross through a walled pass in the Caucasus. Byzantium—itself only a fading, overtaxed rump of the Roman Empire—was now subsidizing the participation of two empires in the Great Age of Walls.

To pay for both his walls and Persia’s, Justinian ransacked the Empire as thoroughly as any barbarian horde. The new tax required to support the garrison at Thermopylae nearly crippled the imperial economy. Justinian was forced to stop all salaries paid to physicians and teachers. He also confiscated the municipal funds of every city in Greece, leaving the towns in such woeful straits that they could no longer keep their streetlamps burning. Without public support, theaters, hippodromes, and circuses shut down. The Hadrianic dream of a civilized people living securely and comfortably behind walls was no longer even a goal. Laughter, wrote Procopius, was no more; the people knew only sorrow and dejection.

None of this sacrifice impressed the Empire’s enemies. In the late 550s, another round of Huns arrived, seeking women as much as loot. They encountered little resistance from the exhausted Empire. One division targeted the region north of Constantinople, where it found the Anastasian Long Wall undefended and in disrepair. The barbarians stopped to pull down a part of the wall, “setting about their task with the nonchalant air of men demolishing their own property.” Not even the sound of a barking dog disturbed them.

Increasingly unable to build or maintain walls, the Byzantine Empire gradually shifted toward other strategies—careful intelligence gathering, diplomacy, the buying of allies, and, above all, the bribing of enemies. But the legacy of Justinian lingered. The autocracy and higher taxes required by his walls and wars became fixtures of Byzantine life. “I am told I am free, yet I am not allowed to use my freedom,” a citizen once complained to him. Another fifty generations of Byzantine citizens would make the same complaint.

In the end, the only Byzantine walls that mattered were the walls of Constantinople itself. They were the one constant in a state whose borders routinely collapsed upon the capital. If the walls of Constantinople fostered a bunker mentality, they at least did their job, and at times what was at stake was much more than the preservation of a doddering empire. Twice between 674 and 718, Arab armies laid siege to Constantinople, and both times the city withstood the assault. The second of the two sieges, when the caliphate dedicated as many as two hundred thousand troops to defeating the Christian capital, is widely regarded as one of the greatest turning points in history. The Empire, such as it was, still played a crucial role in organizing the defense of the West. As long as the walls of Constantinople held out, they halted the Western advance of Islam and allowed Western civilization to continue to develop upon its Christian and classical roots. By contrast, the Persian Empire—defended by long walls facing the wrong direction—had already fallen to Arab armies. The consequences of those simultaneous wars reshaped the cultural and political map of Eurasia. Even faraway Chinese chroniclers took note—not that they didn’t have troubles of their own.