In the thousand years after the construction of the First Emperor’s Long Wall, the spread of border walls transformed societies across Eurasia. With the ages-old duty of citizens to perform occasional military service largely commuted into an obligation to support distant border walls through taxes and labor, civilians were relieved of any direct military role, and as the ancient world drew to a close, bristling with Gogs and Magogs of ever-increasing menace, the security of virtually all of Eurasian civilization depended upon just three states. The emperors of China, Persia, and Rome inspired little love for their efforts. They were widely despised for their taxes, their forced labor, their unruly barbarian mercenaries, their arrogance, and their caprice. Citizens across all three empires sometimes imagined they might be better off under the barbarians or at least escaping to some otherworldly realm offered by religion.

Of the three, China lasted longest and had the most complicated relationship with walls. In the churn of dynasties and emperors that makes up most of Chinese history, the great border walls rise and fall to their own rhythm. They are in turns ignored, defended, skirted, breached, debated, extended, and repaired. Great lengths of ancient walls survived from one era into another, tacitly goading new generations of emperors to compete with emperors past. Rulers, drunk on unchecked power, repeatedly envisioned the impossible. They conscripted ten thousand men to labor on their walls, then a hundred thousand, a million, 2 million.

For most of Chinese history, the question is not whether the walls worked but whether they were worth the trouble. Was the threat of invasion greater than the horrors of despotism, which ruined so many men on work crews on distant frontiers?

The walls alone have seen the truth, and they are mute.

* * *

The long history of the Chinese long walls was nearly cut short in the second century. Across China an oppressed peasantry finally vented its hatred for the dynasty that had taxed and conscripted them to support the building of walls and paying of bribes to barbarians. The targets of their rage were not the barbarians, who seemed, for many at least, a distant and rather abstract source for their troubles, but the emperors, who were for them the face of oppression. In the late second century, around the time that Marcus Aurelius was struggling against the first major collapse of the Roman frontiers, rebel leaders rallied peasants against the Han. A mostly barbarian force, composed of soldiers who’d formerly been tasked with defending China, drove the young emperor and his court from the capital at Lo-yang in AD 189–90. Thousands of hungry refugees followed in the wake of the displaced monarch, scrounging for food. When the walled frontier collapsed, there was little that the northern settlers could do but stream south in enormous numbers hoping to find refuge in safer territories.

Ninety years later, in AD 280, the founder of the short-lived Western Jin dynasty, Sima Yan, reunified China. Sima Yan was a contemporary of the Roman emperor Diocletian’s, and like Diocletian, he embarked on the construction of new border walls. A Confucian scholar apparently didn’t see the point. “Trust in virtue, not in walls,” he counseled. As for the emperor, he celebrated his victories with such a large collection of concubines—over ten thousand reputedly—that the task of selecting a nightly lover finally exhausted him. Leaving the matter to fate, he resorted to riding around the palace in a goat-drawn cart, allowing the goats to choose his lovers. Virtue was not Sima Yan’s strongest suit.

The emperor’s walls only created a facade of national unity. Within a few years of Sima Yan’s death, internal squabbling had resumed under the weak hand of his eldest son—the one widely regarded as a moron. The titles that Chinese historians posthumously awarded the Western Jin emperors attest to the ruling family’s rapidly declining fortunes: the “Martial Emperor” was succeeded by the “Benevolent Emperor,” who was followed by the “Missing Emperor,” and finally the “Suffering Emperor.” The latter ended his days waiting tables at a barbarian feast.

In the troubled half-century of their rule, Sima Yan and his descendants learned a familiar lesson, only destined to become more familiar over time—that a wall is only as good as its defenders, many of whom tended to be warlike foreigners of dubious loyalty. In AD 304, a Hun chieftain in Chinese service had the serendipitous recollection that one of his ancestors was a Chinese princess who’d been bartered off to the barbarians in hopes of buying peace. Via this slender claim to the Chinese throne, he declared himself emperor. The great walls could offer little protection when their defenders had turned against the state. Hun warriors overwhelmed Chinese defenses and in AD 311 sacked the capital. Thirty thousand townspeople died. The grand city itself was burned. The survivors scattered and took to the roads or to crime. In areas that had been overrun by the Huns, agriculture ground to a halt. Some refugees fled to the mountains. Most streamed south to where ethnic Chinese maintained traditional culture in a more secure environment.

For the common man, Buddhist monasticism now offered a radical alternative to a chaotic world, but the appeal of the religion, still relatively new to China, was not strictly spiritual. Monks alone escaped the heavy burdens placed on the Chinese by the need to fortify long borders. While new emperors conscripted yet another round of hapless peasants to build new walls, monks enjoyed an exemption from all physical labor. Buddhism spread rapidly in those northern regions that were home to the border walls.

* * *

For those who eschewed escape into a monastery, there was always work, overseen by the emperors from their position of absolute despotism. Whenever the old walls sank into obsolescence, new walls were ordered to replace them. One dynasty after another tried their hand at civilization’s oldest strategy—using their building prowess to construct a durable defense. The Northern Wei emperors (AD 386–534) mobilized some one hundred thousand workers toward that end, following the advice of those urging them to construct walls to alleviate “anxiety about border defense.” Not to be outdone, their successors, the Northern Qi, put even larger crews to work on walls. The new dynasty’s mad founder, Wenxuan, who kept a crowd of prisoners close at hand for those moments when he would fly into a drunken rage and feel the need to torture or kill someone, mobilized his peasants to construct another 133 miles of barriers. These walls—the pride of an emperor who once beat his son silly for being too squeamish to carry out an execution—were but a prelude to the 300 miles of walls built in 552, and those were but a prelude to the walls that, by 556, extended China’s fortified frontier all the way to the sea. Nearly 2 million men wrestled stones into place or heaped and tamped dirt while their emperor streaked naked, caroused both day and night, and dismembered anyone who offended him. By the time Wenxuan died in 559, his walls traversed over a thousand miles. His mourners, such as they were, strained to demonstrate sadness, and only one was able to force a tear.

The new walls spread across the border like a fast-growing vine—a hundred miles here, another hundred there—yet distance alone understates their impact. Measured in men, they loom even larger. Emperor Wen dispatched 30,000 men to build a wall in AD 585, then 150,000 the next year, and another 100,000 again in the year after that. Wen’s son Yang outdid him, sending a million men on a wall-building campaign in 607, followed by another 200,000 in 608.

Of the great wall builders, Wen was unusual in almost every respect. Frugal and sympathetic, he reduced taxes and banned luxuries from the palace. In 595, he forbade the production of weapons and confiscated any that already existed. The edict exempted only his home province. Wen’s policies set China on a starkly different course from that taken by the contemporary, post-Roman West. While Europe was militarizing during its Dark Ages, as aristocratic families that had once prided themselves on their libraries, luxuries, and civil service constructed timber castles and assembled private armies, China was pushed ever deeper into the civilized world of workers and wallers.

Wen’s strategy had its benefits. It enabled a walled and predominantly civilian China to advance during a time when Europe largely stagnated. However, it also solidified the subjugation of the Chinese to their despotic rulers. Wen’s benevolent paternalism was rare, at least among emperors. More common was the attitude of his son Yang, who viewed his defenseless subjects as commodities, easily replaceable and in endless supply. Like Hadrian, Yang was something of a know-it-all, who tried his hand at many things and found it annoying when other people showed more talent. A determined poet, he once produced the following quatrain:

I wish to return but cannot do so

Alas, to have encountered such a spring!

Songs of birds compete to urge more wine,

Blossoms of plums smile to kill people.

When two poets created superior works, Yang had them put to death. In retrospect, they never stood a chance. How could they have written anything worse?

The casual student of history too easily forgets that the great advantage of democracy is not that it guarantees the will of the people—such a thing hardly exists—but that it prevents the madness of despots. Scholars estimated that half a million workers died on the despotic Yang’s walls, and that wasn’t the end of it. The walled frontiers, positioned far from China’s agricultural heartland, required a constant flow of supplies, and in the early seventh century Yang undertook construction of the Grand Canal to support the wall’s defenders. Five million workers labored along its eleven-hundred-mile course. When it was done, the Grand Canal connected the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers to some thirty thousand miles of local waterways, allowing China to achieve a unity unprecedented among the Old World empires. The canal was a wonder, but it didn’t come cheap. To the number of workers who died in its construction must be added those who died in the famines caused when Yang’s conscriptions carried off so many peasants that there weren’t enough field workers to tend the crops. Chinese historians logged numerous complaints about the project: the construction never ceased, the people were exhausted, and, worse, Yang used his troops to control the people. Could building the wall and the canal that supplied its defenders have cost more lives than the wars it prevented? This didn’t square with Yang’s calculations. He celebrated his new wall in characteristically artless verse:

Building the wall is a stratagem that will benefit a myriad generations

Bringing peace to a hundred million people.

Peace, of course, is a worthy goal, but it is possible the wall worked too well, at least from Yang’s point of view. The Chinese, uninterested in vilifying foreign enemies who could not penetrate the frontier wall, united instead against the emperor who made them build it. Tales of Yang’s tyranny took on a new life after his death. A hundred years after his court spent its final night in oblivious partying, while rebellion closed in on them, Yang became a figure of legend. Storytellers wrote of how the emperor had buried fifty thousand workers alive, headfirst, for the crime of having dug parts of the Grand Canal too shallow, how he’d employed a million workers to build a vast pleasure garden and tens of thousands more to construct a labyrinthine pavilion where he could privately pursue his aphrodisiac-driven sexual desires. All this is to say nothing of the women he forced to haul his enormous barges up the canal, their punishment for not making the cut for his harem.

* * *

The next dynasty repudiated Yang’s walls. “Emperor Yang exhausted the country in building long walls,” announced a Tang emperor. He preferred to defend the Empire with Turkish steppe warriors. The Empire itself continued to unite and divide as it always had. New dynasties brought new despots, and new despots typically brought new walls.

It wasn’t until the thirteenth century that a genuine existential threat arrived at China’s borders, unexpectedly vindicating all those infamous emperors who’d been convinced that there were worse fates than conscript labor. The shock of the Mongol conquest reweighted the balance sheet of Chinese strategy. Will half a million die in construction of a new wall? Small price compared to whole cities burned, their inhabitants put to the sword. Will the people suffer from exhaustion and overtaxation? At least they’ll have their lives. Could a wall protect China for “a myriad generations”? Maybe this time. A dozen dead despots, reviled for the crimes they’d committed to fortify China’s borders, smiled in hell.

The nation that would have such a profound impact on China emerged somewhat belatedly out of the swarm of tribes occupying the steppe to China’s north. Prior to the twelfth century, the Mongols were generally indistinguishable from other sheep-herding steppe warriors whose confederations rose and fell over time. They moved about with their animals, forever squabbling with their neighbors, such as the Tatars, with whom they were later confused. To the Armenians, they were the “nation of archers.” To the West, they were the Tartars, a nation sprung straight from hell (“Tartarus”). Like nearly all unwalled peoples of the premodern world, they dedicated their men to war. A modern historian has observed that for the Mongols “the whole of life was a process of military training.” Every Mongol male learned fighting skills. Boys learned to ride and shoot as toddlers, and with that training came a brutal toughening process that taught them to endure hunger, thirst, and cold. Even the annual hunts, during which the entire army formed a vast ring that slowly encircled its prey, served as exercises in discipline.

Genghis Khan once remarked that man’s greatest joy lay in cutting his enemy to pieces, seizing his possessions, making his loved ones cry, and raping his women. Whether any of this is true, I lack the experience to say. At the very least, Genghis’s pronouncement captures the spirit of the nomadic warriors he collected into his war machine. Genghis knew that the strength of his host lay in its rough-and-tumble lifestyle, and in his Great Yasa he forbade any of his men from moving into a town and adopting a sedentary life. As if to bolster this decree, he insisted that his Mongols should not show favor to any particular faith, religion being the stuff of cities, temples, mosques, and books—all things of no value to the Mongol soldier. Urban life was entirely distasteful and alien to him, and he intended it to remain so for his men as well. To Genghis, the Mongols would always be “the people whose tents are protected by skirts of felt,” men whose loyalty he rewarded “with things he takes from earthen-walled cities.”

Ah, those earthen-walled cities! How it disgusted Genghis to contemplate men living in such fashion. Like most barbarians, he never quite understood that the treasures he coveted were only produced by people living behind the walls he disdained. In the early-thirteenth century, he passed bloodlessly through China’s border walls, the gates having been opened to him by Chinese subjects who could not imagine anything worse than their tyrannical emperors. To put it charitably, their decision ranks as one of the greatest miscalculations in history. Genghis initially demanded a heavy tribute of gold, silver, satins, and other luxuries, but this tribute stayed his hand for only a year, after which he impatiently manufactured an insult and broke the peace. He also declared himself insulted by the Tanghut people who occupied northwestern China. “The Tanghut are people who build city walls,” observed one of his advisers. “They’re people whose camps don’t move from year to year. They won’t run away from us carrying off the walls of their cities.” This was in summary the nomad’s view of the civilized wall builders: sitting ducks whose occasional slowness in forking over their wealth offended the natural order in which civilized folk paid craven tribute to superior barbarian warriors.

The Mongols possessed a ruthlessness rarely found even among warrior peoples. When assaulting city walls, Mongol generals mercilessly placed Chinese captives at the vanguard of their assault forces, knowing that the city’s defenders, recognizing their relatives in the firing line, would hesitate or even refuse to unleash their arrows upon them. Mongol rank and file unflinchingly obeyed commands to commit genocide and seemingly thought nothing of meeting quotas for numbers of civilians slaughtered. In one town, a general might order his men to slaughter five townspeople apiece. In another, he might command them to slaughter forty. The soldiers carried out these commands and moved on to the next town.

Two decades of civilian massacres all but depopulated northern China. When Beijing surrendered to the Mongols after a long siege had left starved inhabitants resorting to cannibalism, the Mongols turned the city into a slaughterhouse. Fires burned for a month, while bones lay in heaps, unburied, the ground all around still oily from human fat.

At one point, the Mongols considered destroying all of China, with an eye toward razing the earthen-walled cities and using the land for pasture. A Chinese adviser convinced them they’d be better off with millions of cowed tribute-payers. In retrospect, they seem to have split the difference. The population of China fell from around 120 million in 1207 to less than 60 million in 1290, with most of those losses occurring in the battle-scarred north, a region that included not just the walled frontier along the steppe but the Yellow River itself, ancestral homeland to Chinese culture. The Mongols could boast that they could ride over the sites of many former cities without encountering any ruins high enough to make their horses stumble. To Genghis, who regarded the fact that he still ate simply and wore rags as proof of his righteousness, the destruction of China had been foreordained. “Heaven is weary of the inordinate luxury of China,” he said.

* * *

China’s new Mongol rulers lacked any appetite for great walls. Not even Genghis’s cosmopolitan grandson, Kublai Khan, for all his public appreciation of Chinese culture, could be bothered with such a traditional use of resources. For a hundred years, the Chinese people—what few were left—were finally allowed to rest from their monumental labors. Five generations were born never knowing the experience of shoveling windblown loess for a madman. They had only the folk stories to weigh against the tales of Genghis Khan. And when they had lived under the Mongols until they could stand it no longer, they finally produced a new dynasty and resumed work on their walls.

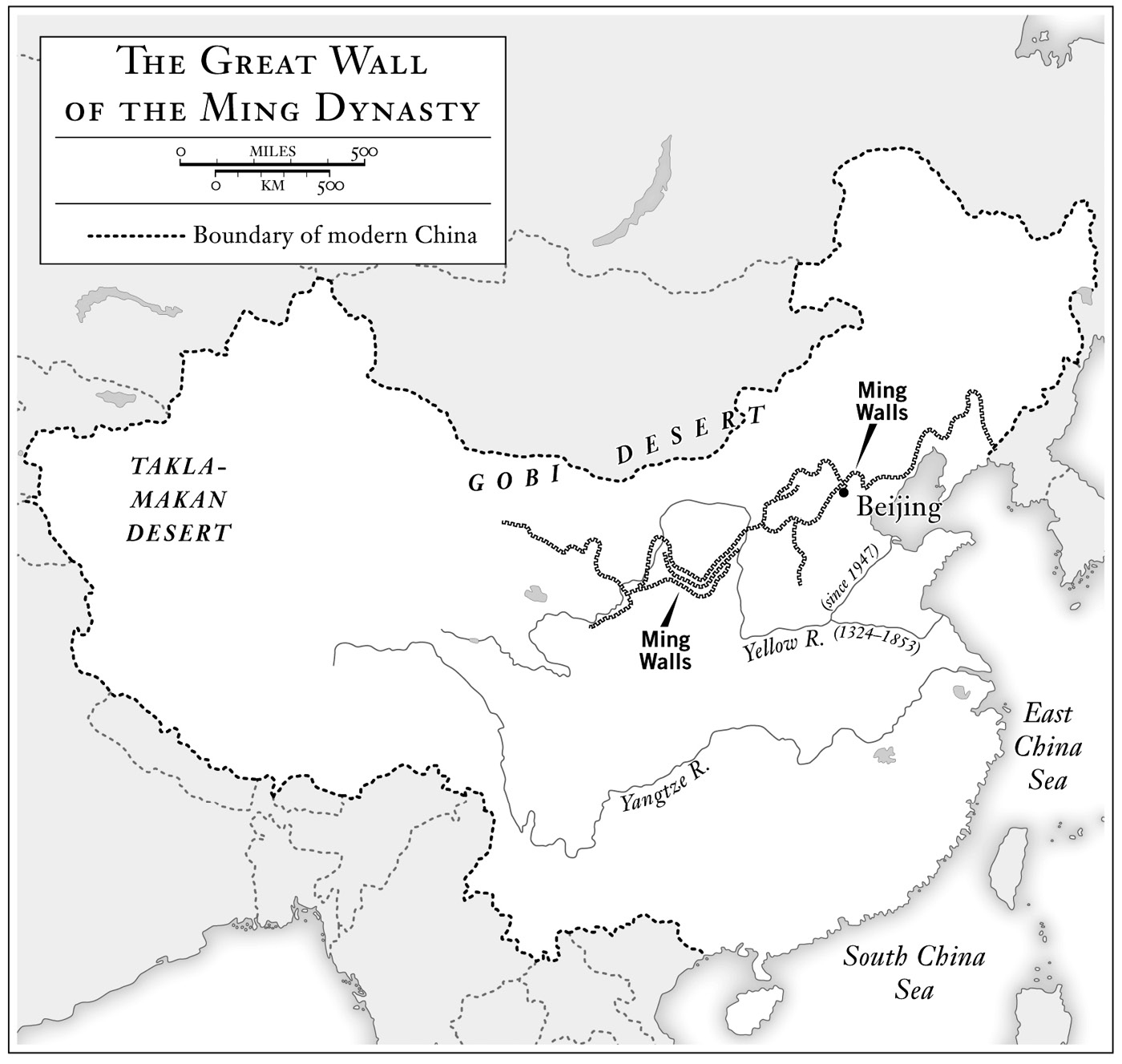

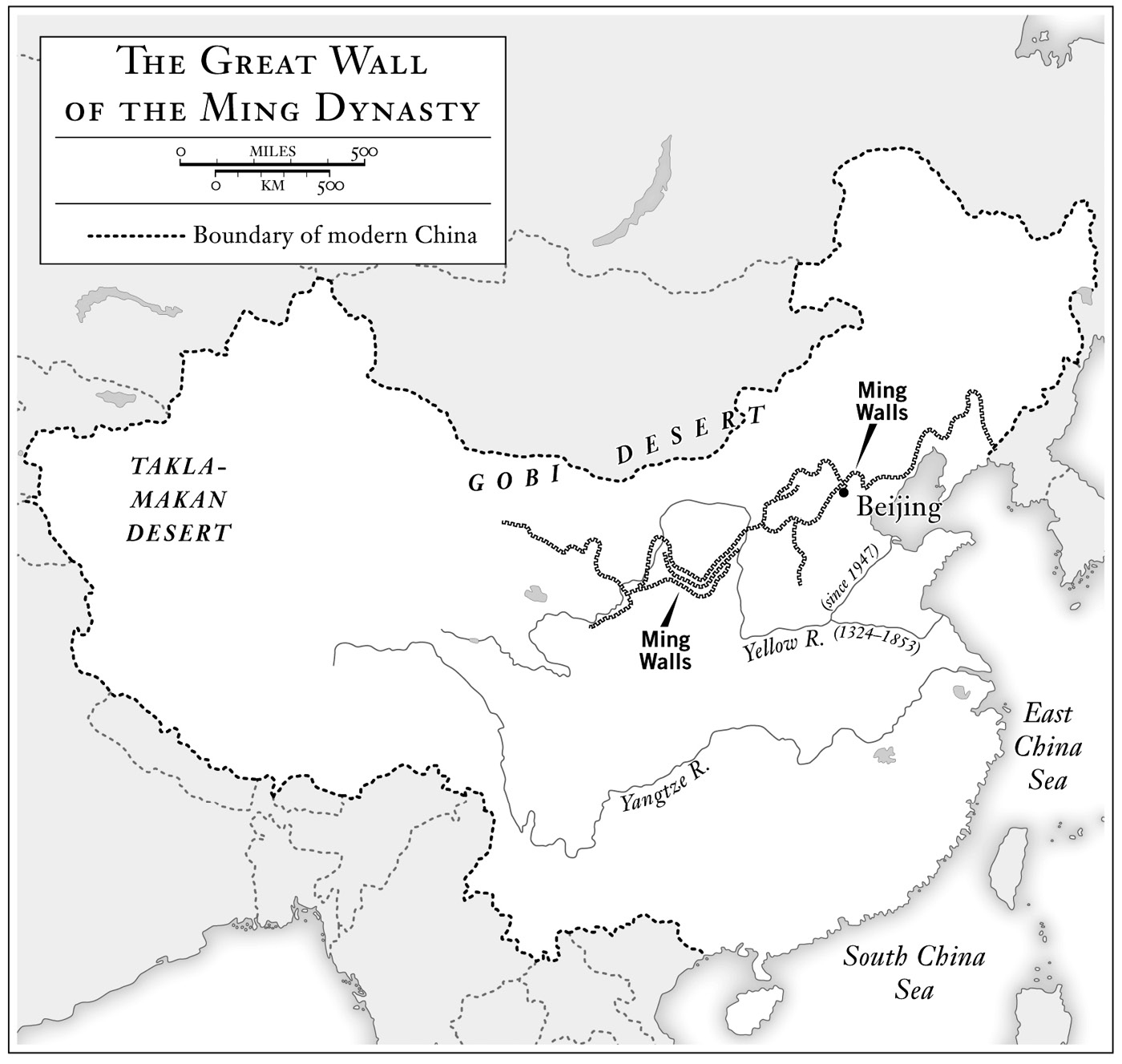

The Ming era (AD 1368–1644) took root in long-simmering Chinese resentment toward Mongol overlords. Zhu Yuanzhang, the founder of the dynasty, believed himself on a divine mission to restore a true China. He attempted to remake China as he imagined it had once been: ethnically and culturally homogenous, uninterested in universal empire, and resolutely focused on the defense of its limited borders. He also envisioned the Chinese state as a nation enclosed. In the instructions he left to his successors, Zhu warned future emperors against seeking conquests, instructing them instead to maintain a strong defense. The early Ming, obedient to these principles, rebuilt the city walls destroyed by the Mongols. Thousands of walled cities again populated the map of China.

Some later Ming emperors, temporarily enjoying a respite from Mongol raids, chose to ignore Zhu’s advice and even flirted with naval policies that might have made China master of the seas and colonizers of the New World. Chinese fleets reached the coast of Africa. However, it would not be China’s destiny to beat the Portuguese in the race to establish a sea link between Europe and Asia. In 1433, the revival of Mongol power revived old fears. The emperors abruptly reined in their maritime ambitions. Isolationist-minded advisers, never fans of overseas adventuring, won the day, pointing to a loss suffered by China’s great fleet off Vietnam, and more important, the need to retrench in the face of a resurgent Mongol threat. The Empire scuttled the largest navy in the world and turned its back on exploration. In that same decade, though China’s engineers had overcome the technical obstacles to providing year-round water to the north, the country’s officials chose to withdraw from garrisons that couldn’t be easily resupplied by sending materials up the Grand Canal. The frontier lines were brought in by nearly two hundred miles.

A military disaster precipitated the country’s final retreat behind walls. In 1449, the Mongols invaded yet again. Taking personal command of his troops, the young emperor, Yingzong, set out to find and punish the invaders. When the Mongols attacked his camp at Tumu, they destroyed most of the army and captured the emperor. The Tumu Crisis ended any lingering possibility that the Chinese would look outward like those Western nations already dispatching traders and explorers to new lands. From that time on, the Ming would follow the advice of their founder. They would shut themselves in, eschew cosmopolitanism, cling to tradition, and concentrate on defense. The emperors would redirect the nation’s energies to building walls. The Mongols had left them no choice.

In the Ming era, the familiar role of the ruthless despot is conspicuously missing. While court officials exchanged theories of national security, the emperors allowed local officials to construct new walls, improve old ones, or fill important gaps, utterly unaware that they were overseeing, in this patchwork fashion, the construction of a Wonder of the World.

The Great Wall now took form in fits and starts, in unconnected stretches in often remote regions. New lengths were added whenever the Mongols found an existing gap and exploited it. During the Ming era, the Chinese were forced to fight nearly two hundred wars against the Mongols. As the gaps in the Wall gradually filled, knitting together the Ming defenses, the Mongols found it harder and harder to break through. The Wall was, for all its modern detractors, effective at its task. It fended off attacks by Mongol raiding parties numbering in the thousands.

In 1576, a minor Mongol raid precipitated the Wall’s final significant redesign. The proximate cause of the raid was, according to one leading wall researcher, the fury of a woman scorned. The woman, known only as the Great Beyiji, was one of at least one hundred wives abandoned by the Mongol chief Sengge (1522–86), a man who “dissipated himself with wine and women, spending all day groaning in bed.” His scorned wives, supported by their clansmen, periodically swarmed the Chinese border, where, letting on that they were still in cahoots with Sengge, they demanded vast tributes. The Great Beyiji was particularly obnoxious, insisting on satin robes and other fineries “stacked up in mounds,” along with “innumerable” cattle and sheep, and great quantities of grain. When the Chinese, in 1576, finally refused her requests, a male ally of the Great Beyiji led his seventy men along a woodcutters’ path through the Wall, where they slaughtered a small Chinese garrison caught sleeping in their barracks. A pursuing Chinese force subsequently fell victim to ambush. The next year, construction began on a new brick wall in the area—the first prototype of the Wall so admired by tourists today.

Reconstructed in brick, the Ming walls were the grandest of all the barriers built against the steppe. Estimates of their length vary tremendously—three thousand miles? Ten thousand? Amazingly, the full course of the border has never been surveyed, yet even the most conservative numbers suffice to highlight the immensity of the project. It is the Ming walls that finally earned the moniker great, attracting tourists the way they once repelled raiders. The Ming walls roll across hills and mountains, sometimes in masonry and brick, often resting atop huge granite blocks.

In the twenty-first century, historians continue to discover other Ming defenses, long overshadowed by the Great Wall. Far from the steppe, for example, the Chinese had walled off their southern border. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the emperors deemed the highland Miao of Vietnam a threat great enough to merit hundreds of miles of walls, and perhaps they were right: the Miao destroyed one border wall in the seventeenth century, and the Chinese were still building stone barriers in the region as late as 1805.

The Ming emperors were no more successful than their ancient predecessors in selling the idea of the Wall to the people they drafted to build it. Nearly two thousand years had passed since the time of the First Emperor’s Long Wall, and public opinion in the Ming era was so hostile to the memory of it that the emperors were careful not to use the term Long Wall at all. The usual poetry of resentment circulated: folk tales of a nation crushed by the work of it all. How could mere humans have produced such a prodigious monument? Mostly through supernatural assistance, apparently: a supervisor is assisted by an old man who knits the wall out of brambles; workers see a length of silk falling from the sky and use it as the inspiration for moving granite blocks down a giant ice slide. Apparently, the supernatural did not extend its assistance to the Chinese at war. In the seventeenth century, the barbarian Manchu were let through by a disloyal Chinese general.

The Manchu were as foreign to Chinese civilization as any nation from the steppe. At first, the conquerors could hardly tolerate walls of any type. If they occupied a building, they’d sometimes knock down the walls, leaving only pillars to support the roof. They also refused to play the traditional role of barbarians assimilating into Chinese society. Like the ancient Spartans, the Manchu preferred their homeland not be contaminated with too much civilization. They clung to their traditional ways and even forced Chinese men to adopt Manchu hairstyles. They ridiculed the Chinese, but especially their walls: “The men of Qin built the Long Wall as a defense against the barbarians,” wrote one historian for the Manchu. “Up went the Long Wall and down came the empire. People are still laughing about it today.” As for the Great Wall, the Manchu wrote an epitaph:

Endlessly they built walls, without ever pausing for breath.

The builders worked from dawn till dusk, and what was the use?

* * *

A Chinese author once reflected on the history of his nation with a resigned fatalism: “The empire, long divided, must unite: long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been.” The author who added these words as an introduction to the bloated fourteenth-century epic Three Kingdoms can be forgiven his cyclical view of history. Time and again, the Chinese had succumbed to the cyclicality he so succinctly described. Time and again, barbarians had crashed down upon the Chinese and seized control of the northern regions. Sometimes the invaders were mercenaries who turned on the people they’d been hired to defend. Either way, China’s unity would be broken. Millions would flee south, leaving the defense of the north in the hands of upstart, barbarian dynasties. The new defenders would learn to build walls. China, wherever or whatever that was, would go on. The walls, like China itself, outlasted the Empire, but not because they stood forever. Once built, the walls had to fall; once fallen, they had to rise again. Thus it was for the walls, just as it was for China.

For the author of the introduction to Three Kingdoms, it was enough to observe the cycles of Chinese history. Historians, however, must view those cycles in their broader context, and some cycles are more important than others. The Ming-era retreat behind the Great Wall wasn’t just another turn of the wheel. The rise of the West owed much to the timing of those Ming walls, which prevented newly walled Chinese from competing with a burst of expansion by the West. The rise owed perhaps even more to the failure of walls in another vast and important region.