In the early-nineteenth century, some four thousand years after kings and pharaohs first began inscribing bricks and tablets with bombastic announcements of their great walls, a British poet penned a sonnet about a statue that had once squatted in the sands of Egypt. The poem contrasted the boastful inscription of a long-dead king with the desolation of his former domain. Its fourteen lines are among the most famous in the English language, and more than a few of us gratefully acknowledged their admirable brevity in selecting a work to memorize for our high school literature class. Even the trauma of declaiming the poem before an audience of bored gum-chewing classmates couldn’t entirely diminish the power of the last stanza:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

At the time Shelley wrote “Ozymandias” as a belated epitaph for a dead civilization that had long ago fallen into ruin, the contrast between the poet’s home—a rapidly industrializing Britain, swarming with inventors, engineers, scientists, philosophers, writers, and artists—and the ancient cradles of civilization was nearly total. At least Egypt still had its statues. In Western and Central Asia, the magnificent Bronze Age cities had been reduced to piles of dirt. So thorough was their oblivion that almost no one seemed to have given any thought to what lay beneath the great mounds until an amateur antiquarian and employee of the East India Company took an interest in the remains of Babylon in 1811. Real excavations wouldn’t commence for another three decades. Over the nineteenth century, archaeologists and antiquarians trickled over in greater numbers, steadily unearthing a world long disrupted—ancient canals filled with silt, tablets inscribed in obscure, forgotten scripts. All about them as they worked, the excavators saw nomadic herdsmen with their flocks. Lions and other predators still roamed. While railroads and telegraph lines crisscrossed the Western European homelands of the archaeologists, the territories of Mesopotamia and neighboring regions were less urban and more pastoral than they’d been in the days of Gilgamesh, four thousand years earlier. Bedouins still raided traveling parties, and mountain nomads still menaced the cities.

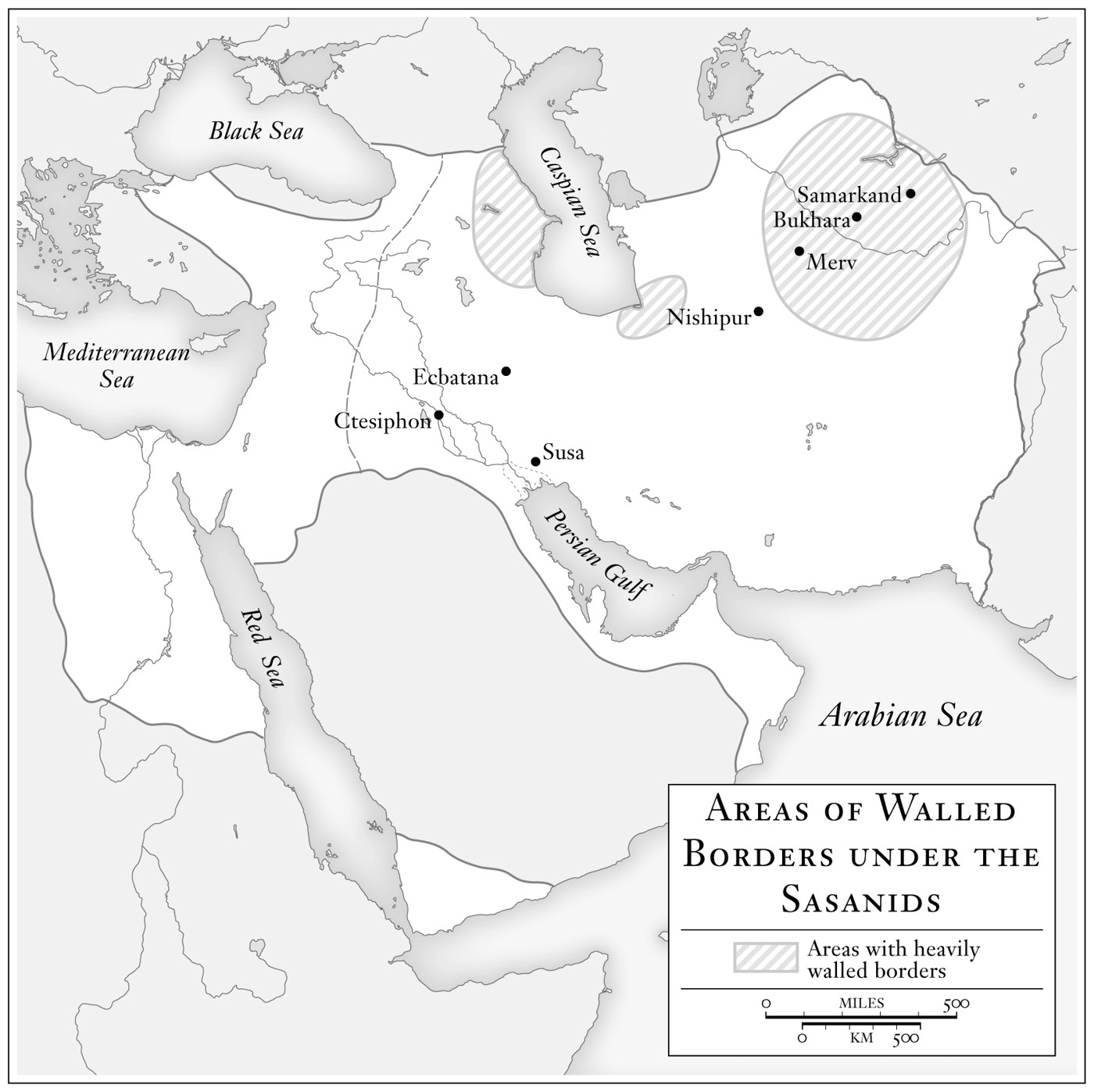

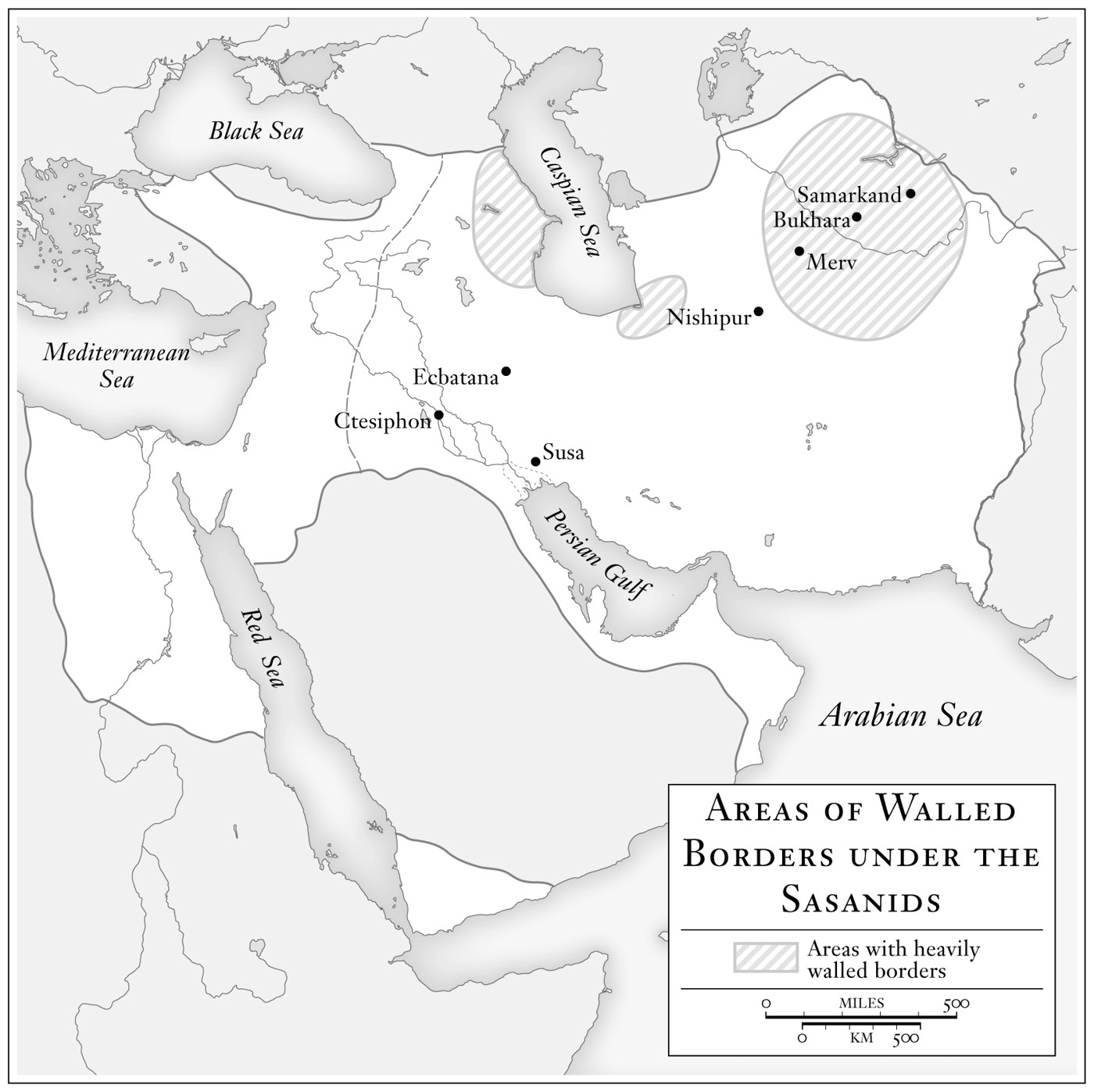

The ancient founders of the civilizations that once flourished in these ancient lands had originally defended themselves from the nomads with city walls. In time, the Ozymandias-like kings of Ur had mobilized their basket carriers to erect the first border walls, and more than a thousand years after that, the kings of Babylon had ordered the construction of even grander walls. It wasn’t until the Great Age of Walls, however, when China and Rome were erecting fortifications that ran for hundreds of miles, that an empire finally dedicated its resources to a more comprehensive defense system in the heartland of civilization, strategically placing barriers intended to seal off all of Western and Central Asia.

The Persian fortifications, like the Roman, have only a short history. It is a dark comedy of sorts, a tale of walls intended to resist an old enemy from a familiar direction, completed just before the arrival of a new enemy from another direction. Later, when those walls might still have been pressed into service to save the ancient cities from a second, more devastating invasion, there were no longer any guards in the towers or patrolling the walkways. Send in the soldiers? Too late for that. Send in the clowns.

Despite its twists, the story of the border walls of Western and Central Asia occupies a special place in history, partly because it illustrates the great stakes that were always at play with ancient border walls, but mostly because the consequences of abandoning the walls has influenced the world geopolitically and culturally ever since. It was the beginning of a great turn in world history, an unexpected pivot that saw an enormously important part of the world begin its descent into obscurity. In the later Middle Ages, a vast and populous region that had radiated art, culture, and political power long before either Rome or China fell strangely silent. It has never fully recovered. Today, the map of Western and Central Asia is populated by an array of struggling nations, each characterized by varying degrees of violence, repression, poverty, and closed-mindedness. The descendants of the old Persian Empire include Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Syria. In all of them lie the remains of forgotten walls, like colossal wrecks, boundless and bare, where lone and level sands still stretch far away.

* * *

The Persians, who built most of the Western and Central Asian border walls, had little hand in the creation of the ancient civilizations of Asia. Much like the barbarian dynasties of northern China, they inherited most of their walled cities through conquest, having overcome the Babylonian border walls in the sixth century BC. The Persians only gradually adapted to the settled habits of the countries they ruled. In their early years, they perfected little more than the art of unleashing arrows from the back of a horse. Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BC, reported that the Persians taught their young just three things: riding, archery, and truth telling. Having become the possessors of palaces and cities, they eventually fulfilled the prophecies of those Western and Chinese thinkers who argued that civilization dulls the warrior’s edge. In the fourth century BC, the Empire fell to Alexander the Great.

Alexander transformed the landscape of Western and Central Asia, replacing the age-old temple towns with Greek cities. Although popular tradition credited Alexander with supernatural powers in the defense of civilization, his Greco-Asian world was in reality short-lived, falling to various steppe peoples, some of whom reestablished a smaller version of the old Persian Empire, under the Parthian dynasty. For a second time, a nation of horsemen reigned over a civilization they had initially intended only to raid, and like their predecessors, the Parthians gradually learned to think of defense in the manner of civilized folk. Just as the Romans had built colonies fashioned after their rectangular military camps, the Parthians eventually rebuilt the ruined rectangles of Alexander’s Greek cities to reflect the circular arrangement of their own camps. Towns such as Merv, once a proper Greek quadrilateral, were given ring walls. Meanwhile, Parthian art finally adopted new styles, as the rulers, gradually losing touch with the tastes of the steppe, began at last to “swallow the Greek poison.” By the third century AD, the Persian state was sufficiently prepared to receive a dynasty wholly committed to urban civilization and wholly separated from the society of the steppe. That new dynasty—the Sasanid—developed the idea of an Iranian nation that had to be defended in the manner of other great empires. The Sasanid shahs brought elegance and sophistication to Persian culture. They also brought a quintessentially civilized view of the world, and a plan of protecting the entire Empire with walls.

The Sasanids were the first Persian rulers to erect colossal fortifications on the borders of their realm. As early as the mid-fourth century, Shah Shapur II (r. 309–79) revived the old idea of protecting Mesopotamia with a wall. The immediate threat to the Land between the Rivers came from the Arabs, against whom Shapur campaigned ruthlessly. For his policy of threading ropes through the shoulders of Arab prisoners, Shapur acquired the sobriquet “Lord of the Shoulders.” He constructed the so-called Moat of Shapur west of the Euphrates to hold off these desert enemies and made the wall part of a broader defensive system.

Toward the end of Shapur’s long reign (its longevity benefited from his having been crowned while still in his mother’s womb) the Huns announced their presence in Western Asia, arriving through the Caucasus Mountains to “fill the world with panic and bloodshed.” The rattling of Alexander’s gates shook two empires. Both Rome and Persia were directly imperiled, and the rapprochement that followed was heartwarming, as long as you don’t examine it too closely. The two ancient foes fell into each other’s arms like star-crossed lovers in a romantic comedy and, in the grip of mutual goodwill, tempered by terror, agreed to collaborate on a joint effort to limit the Huns to the steppe. Emperor and shah signed treaties to the effect that Rome would bear half of the costs of Persia’s defense of the Caucasus. That treaty would be confirmed repeatedly throughout the fifth century and, after a rather vicious spat, replaced by a new one in the sixth century.

The Persians put the Roman funds to use as best they could—sometimes fighting the Huns, sometimes paying them just to go away. From time to time, the Persians sought additional capital, arguing that by fending off the barbarians they were defending both empires. Increasingly, Persian strategy had but one aim: walling off the steppe. The Arab frontier was thus ignored while Persian rulers constructed oasis walls in Central Asia, bottleneck walls in Caucasian mountain passes, and long border walls in the plains where the mountains entered the Caspian. The shahs pursued the new strategy at fantastic expense, “bleeding their country,” according to one author. With what money remained after the building projects, they bought off the steppe barbarians with gold, silver, and gems, as well as magnificent robes studded with pearls.

The Persians initiated their building program north and east of Iran in Central Asia, where some of the most ancient cities on earth occupied territory so dangerous that even the great empires occasionally walked away, despairing of their ability to defend it. In the fifth century, these cities turned their river-fed oases into fortified prisons beyond whose walls they dared not venture. The program started at Merv, when the Sasanid shahs took the extraordinary step of walling not merely the great city but the entire Merv oasis, a defensive perimeter of some 150 miles. Before long, Balkh, Bukhara, Bayhaq, Tashkent, Nur, and Samarkand had also extended their walls to encompass not just the towns proper but the oases upon which they were located. All the villages and farms that fed the cities and all their precious sources of water were walled off at the edge of the desert. The world of the Silk Road cities had become small, but it was about to become even smaller. By the end of the fifth century, the shahs had apparently written them off, leaving them well outside the great walls then being built to enclose the rest of the Empire. The Persians, like the Chinese before them, had given up on the region.

Tradition attributes the new Persian border walls to Shah Khosrow I (r. 531–79), who was a contemporary of the Byzantine emperor Justinian and lived only a few decades before the Chinese emperor Yang. In medieval sources, Khosrow appears as a latter-day Alexander, building walls of rock and lead locked by iron gates. He is said to have constructed more than twenty new walls throughout the Caucasus and several more east of the Caspian. The longest, the Sadd-e Anushirvan, bears his name (Anushirvan being a kind of epithet for him). Scientific dating techniques, however, haven’t definitively confirmed tradition. Archaeologists believe that the walls attributed to Khosrow could have been built in either the late fifth or sixth centuries, so it is likely that Khosrow’s father, Kavadh I, initiated many of them, even if he didn’t live to see them completed.

Kavadh and Khosrow were certainly cut from the same cloth. Like all good father-son teams, they worked well together, especially in their joint repression of the Mazdakites, a communistic religious cult that advocated the abolition of private property and the sharing of all wealth and women. Ironically, Kavadh had briefly flirted with Mazdakism as a youth. It was the usual story in which a teenager, nearing adulthood and fancying himself a heroic crusader for justice, falls for the seductions of some impractically radical group, subsequently outgrows the infatuation, and has the remaining members of the group put to a horrible death. The young Khosrow actually handled the purge for his father. Although only a despot-in-training at the time, Khosrow’s final disposition of the Mazdakites was so horrific, so creative in its sadism, that generations of Persian artists seem to have specialized in lurid illustrations of it: the cult members are depicted buried upside down, their feet sticking up as if growing out of a human garden; their leader, Mazdak, must witness their executions before being hung upside down and riddled with arrows. Kavadh and Khosrow had a penchant for such deeds. The father once blinded his own uncle, either by pouring hot olive oil over his eyes or by pricking them with white-hot iron needles (no one could remember which). Upon succeeding to the throne, Khosrow had his brothers and nephews put to death.

It seems that the father was the first to take an interest in walls. In 502, Kavadh learned a firsthand lesson in the value of fortifications when he assaulted a Byzantine city in Mesopotamia. Without any assistance from the Byzantine army, the civilians of the city defended their walls for so long that the town prostitutes eventually took to mounting the ramparts and taunting the shah with displays of their private parts. This was the kind of thing a proud tyrant doesn’t easily forget. However, another factor almost certainly played a part in intensifying his, and Khosrow’s, interest in walls. Between 455 and 522, an unprecedented ten Persian diplomatic missions reached China, the first such travels ever recorded. At least one is known to have carried a letter from Kavadh. Subsequently, Khosrow dispatched several delegations to China as well. For the first time, Persian delegations would have passed through the outer walls of the Chinese Empire, eventually returning to their own land like tourists coming back from a trip to the Great Wall, breathless with tales that must have piqued the imaginations of the shahs.

Whenever or however they decided to wall off their realm, Kavadh and Khosrow already had laborers at hand for the work. The father constructed many new cities, while the son put his civilian labor force to work on any number of infrastructure projects: clearing roads, digging underground aqueducts, bringing new land under cultivation. Once, upon building a city designed to look like Antioch, Khosrow dubbed it “Khosrow’s ‘Better Than Antioch’ ”—a name that, mercifully, failed to stick. Khosrow spared no expense on his public works. To help fund them, he overhauled the tax system. Managing far-flung projects from his personal estate—which was also surrounded by high walls—Khosrow apparently resolved to fortify the Empire with barriers that would stand forever. At the Sadd-e Anushirvan, better known as the Red Snake, or Great Wall of Gorgan, his men had at their disposal only the same windblown loess as the ancient Chinese. Unwilling, however, to settle for a Chinese-style barrier of tamped earth, they dug long canals to supply water for brick making. Every fifty yards or so, they placed kilns. It was an extraordinary effort, but it had a purpose. The builders knew that whereas sun-dried bricks crumble easily, baking them creates a ceramic, like a modern bowl or dish, in which the high heat has chemically transformed the clay. Ceramic is as timeless as any substance on earth, a fact that can be easily demonstrated if you have enough patience and the right genes for longevity. Take a dish, bury it in your backyard, and if you’re still alive in a thousand years, you can dig it up and you will find it hasn’t changed. Eons hence, long after the sun has gone dark, that ceramic will remain unchanged. A thick, well-made ceramic brick is resistant even to hammering.

The Red Snake, which was guarded by at least thirty-six sizable forts and supported by a vast hydraulic system designed to provide water to approximately thirty thousand soldiers, formed only a part of the Sasanid state’s defensive system. A similar barrier, the so-called Wall of Tammishe, ran perpendicular to it, and the two walls may once have intersected in an area now submerged under the Caspian Sea. The great border walls of northern Iran were matched by fortifications on the other side of the Caspian, where the shahs directed especially strenuous efforts toward shoring up the defenses of the Caucasus Mountains. To seal off the route between the eastern foothills of the Caucasus and the shore of the Caspian, the Sasanids constructed no fewer than five barriers, the most visually impressive of which blocked off the plain between the mountains and the sea at Derbent in what is now the Russian republic of Dagestan. Originally constructed in the mid-fifth century, the Derbent wall was funded by annual payments of 136.5 kilograms of gold from the Romans, who designated the money be used for defense against “Alans and other barbarians.”

Posterity exaggerated the Derbent barrier. Succeeding generations, obviously impressed by the rampart, imagined it as a “Great Caucasian Wall” that had once extended the entire distance from the Caspian to the Black Sea. In time, it was attributed to Alexander. It was inevitable that Alexander should appear in the tangled folk histories of the Sasanid walls. By the time the poet Ferdowsi wrote Persia’s national epic, the Shahnameh, around AD 1000, the great conqueror, who had destroyed the original Persian Empire and become a cursed name in Iran, had already been sufficiently rehabilitated to play the hero. And what had Alexander done to redeem himself in Persian eyes? Why, nothing less than build five-hundred-yard-high walls against those northern barbarians, now described as giants, Gog and Magog.

* * *

Horsemen from the steppe never did bring down the Persian Empire. When the men of the north finally arrived in force, the Empire was already gone. Kavadh and Khosrow had walled the wrong borders. The Persian walls, which were built to defend against the Huns, were quiet when the Empire fell. Persia succumbed instead to a different sort of enemy, a new religion that had announced its birth by declaring war on the world. In the seventh century, the armies of Islam found little resistance from a war-weary and plague-ravaged Persia. The Empire, with its dozens of north-facing walls, was taken from the south.

Ironically, the caliphs and sultans who succeeded the Persian shahs quickly adopted the latter’s views regarding the urgency of fortifying the northern frontier. In the early eighth century, Muslim rulers established a border wall far to the north of any of the old Persian barriers. They hoped to protect a vital region of Central Asia that is now part of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Later in that same century, the townspeople of Bukhara beseeched their governor for still more protection from steppe raiders. They complained that the Turks, who’d succeeded the Huns as the dominant menace from the steppe, frequently arrived without warning to plunder their villages and carry off slaves. They pointed to a lesson from their history: in days gone by, they said, a queen had constructed a long border wall and attained respite from the Turks. Who was this queen? We have no name, but she was clearly well-known, a sort of local Alexander, if Alexander is understood to be mostly a builder of walls. The name Divar-i-kanpirak, or Kempirak, which was given the wall subsequently built by the Muslim governor, translates as “old woman” and is not unique. A number of “old women” figure in the landscape from Uzbekistan to Afghanistan. This first wall, which stretched along the banks of the Zeravshan River to Samarkand, was soon supplemented by a second, built in the area northeast of Tashkent. As in China, the price of security created an unbearable burden on the locals, and the Bukharans soon regretted their earlier requests. They complained so much about the effort of maintaining the walls that, after some years, the governor at last “freed the people” and took the field against the Turks. He would have been better served defending the wall. By the tenth century, Turks had overrun most of the old Empire.

Turkish rule was the beginning of the decline for most of Asia. The new rulers—being warriors accustomed to the open steppe—never quite understood how to manage the ancient, walled world they had inherited. In Mesopotamia, old waterworks that had been carefully repaired and expanded by earlier caliphs received little attention from nomadic Turkish horsemen, who simply ignored the necessity of regular maintenance. Wherever the locals abandoned their ages-old tasks, the canals filled with silt, and salty water gradually drenched the fields. In Central Asia, one of the great cities carried on—Merv (now in Turkmenistan) briefly became the largest city on earth—but the border walls were altogether forgotten. No guards were standing watch when the apocalypse finally arrived.

* * *

Gog and Magog were real, as it turns out, even if they appeared under another name. It was Genghis Khan and his sons, freshly arrived from the invasion of China, who reduced the cosmopolitan cultural capitals of Western and Central Asia into sand-blown ruins. Their impact, when they finally rode around the undefended border walls, was everything the prophets of doom had feared and then some. The Mongol conquest of the region from Uzbekistan to Syria nearly exterminated civilization there altogether. Millions died in the genocide, and for those who were left alive, it was difficult to attain even the essentials of life.

It would be anticlimactic, after having seen so many walls built against the steppe and so much mythology develop around the walls’ legendary foils, not to give at least some account of what finally happened to the most ancient of the walled lands. A summary account would begin in 1219, when Genghis Khan turned his attentions to the Central Asian region of Transoxiana, where Tashkent, Ferghana, Balasaghun, and other cities thrived. This would be the end for a resourceful and resilient people. The Mongols returned the region north of the Syr Darya River to its natural state, its landscape marred only by ruins and empty buildings. The old border walls were covered with dust, fading into the deep obscurity that nowadays renders them all but unnoticed, a source of mystery even to the locals. The irrigated farmland that once supported the great cities was deliberately returned to steppe.

As the Mongols moved south, the great cities fell one by one, beginning with Bukhara, which had been a center of learning filled with doctors, jurists, and savants of every religion. The great city’s final days passed swiftly, beginning on that day the inhabitants first looked out in panic and saw the countryside choked with horsemen. Great clouds of dust, kicked up by the horses, turned day into night. Most of the Bukharans fled to the citadel, while an army of twenty thousand Turkish soldiers and citizens met the Mongols and was wiped out. Upon entering the city, Genghis wondered quizzically if the mosque was the palace of a sultan. When told that it was the house of a god, he lost interest, dismounted his horse, climbed to the pulpit, and announced, “The countryside is empty of fodder; fill our horses’ bellies.” He then ordered the cases used for storing the Quran turned into mangers and commanded Muslim priests, teachers, and scholars to serve as grooms. Later, angered by the continuing resistance of the still-unconquered citadel, he ordered the entire town burned and slaughtered every male who “stood taller than the butt of a whip.” As one survivor put it, “They came, they sapped, they burnt, they slew, they plundered, and they departed.”

At Samarkand, the number of the slaughtered rose to fifty thousand. It could have been worse: At Tirmiz, Genghis had his soldiers rip open the townspeople’s bellies in case they’d tried to hide their valuables by swallowing them. At Balkh, the Mongols left behind so many corpses that lions, vultures, and wolves mingled among the carrion without quarreling. The Mongols swept through the remaining towns of Central Asia with dispatch. Merv made the mistake of resisting a bit too strenuously. It took four days for the Mongols to march all the townspeople out onto a plain for their annihilation. The corpses lay in piles so high as to make mountains look like hills. Several people attempted to count the dead and came to a figure of 1.3 million. This had become the inevitable end for cities that resisted the Mongol onslaught. After a while, the numbers of the slaughtered—given as 1.6 million in the city of Herat alone (2.4 million according to another author)—seem to have overwhelmed the survivors’ ability to count.

The Mongols reached the climax of their destructive energies at Baghdad. In the thirteenth century, Baghdad was the city of the caliphs, an intellectual center, home to hundreds of bookstores and libraries at a time when books were scarce in much of the world. When the Mongols arrived in huge numbers, well prepared with Chinese siege engines, civilians from all over Iraq took refuge behind Baghdad’s walls, crowding the streets and stores. However, the defeat of the caliph’s armies doomed the city, leaving too few soldiers to man the ramparts. The slaughter of Baghdad’s citizens went on for a biblical forty days. When it was finally over, the traumatized survivors came out of hiding, their faces drained of all color. They looked, according to one contemporary, “like the dead emerging from their graves on the day of resurrection, fearful, hungry, and cold.” Some eight hundred thousand had died, “not including children thrown in the mud, those who perished in the canals, wells, and basements, and those who died of hunger and fear.” The dead lay in great mounds, exposed to the rain that fell on them, accelerating the putrefaction. Flies swarmed everywhere. A great stench pervaded the air, forcing the survivors to hold onions close to their noses to block the smell. In the meanwhile, floating corpses contaminated the canal water and caused an epidemic.

The fall of Baghdad extinguished the last embers of resistance in Iraq. Iraqi civilians, the descendants of the ancient Mesopotamians, having not even the deeds of warlike ancestors to inspire them, declined even to mount a fight. The contemporary Arab writer Ibn al-Athir of Mosul expressed his disgust at the sheeplike acquiescence of civilians to their fate, not realizing he was simply describing the most ancient of differences between wallers and warriors. He recounted several stories: how a single Mongol had slaughtered every member of a heavily populated village because not one of the villagers had defended himself; how a man patiently waited while his Mongol captor rode off and fetched a sword with which to kill him; how seventeen men were too frightened of a single Mongol not to follow his orders to tie one another up. A thousand things distinguished the civilized Iraqis from the Mongols. The Iraqis could read and write and create an array of products foreign to the Mongol economy, but when the two peoples met, all that mattered was that the Iraqis had lived behind city walls for at least fifty centuries and had little experience of violence.

The slaughter of the wallers was accompanied by the devastation of the infrastructure that had long made civilization possible in dry lands. In western Syria and northern Iraq, nomads drove farmers completely off the land, and this condition persisted well into the twentieth century. The Mongols delivered the coup de grâce to an agriculture in decline, destroying the old irrigation works. Thousands of miles of canals, channels, and ditches fell into ruin. By the twentieth century, only one of the ancient canals still functioned. The Tigris and Euphrates, no longer disciplined by the hand of man, changed courses, as rivers are occasionally inclined to do, bringing disaster. This was the end for many of the world’s most ancient cities.

Similar destruction occurred throughout Central Asia. At Bukhara, Merv, and Gurganj, the Mongols destroyed damns and dikes crucial to the region’s hydraulic infrastructure. Urban life there was largely exterminated. In the Persian heartland, which had no extensive sources of fresh groundwater, civilization depended on the maintenance of underground irrigation channels and access to aquifers. The Mongols destroyed that hidden infrastructure, too. Genghis himself, in a final, gratuitous parting shot, destroyed the granaries of Iran as he left the country.

* * *

The failure of the walls of Western and Central Asia marked one of the great turning points in world history. It was, along with China’s withdrawal behind the Ming Great Wall, one of the key factors in Europe’s sudden rise to global dominance. The West had simply outlasted its two chief competitors.

The survivors, with what energies they had left, rebuilt, minus the bookstores, schools, and other nonessentials. Gone, too, were the old walls, which the inhabitants of Western and Central Asia had been building and rebuilding for longer than any other people on earth. They had once constructed the world’s first city walls and, within those walls, the first civilizations. Of their ancient civilized ways, they now retained mostly the meekness. They put up no resistance while warrior peoples steadily trickled in from the steppe, establishing nomadism where cities had once flourished. In time, the ancient heartland of civilization was reduced to little more than a place for cavalry maneuvers. By the seventeenth century, the population of Baghdad had fallen to just fifteen thousand, a paltry fragment of its former peak. By contrast, the number of wandering tribes in the country was said by one eighteenth-century traveler to be “infinite.” As late as the nineteenth century powerful new tribes of nomads were still filtering into Syria. The nomadic Fid’an, for example, encircled the city of Aleppo in 1811, destroyed forty of the city’s villages, and ate up the entire harvest. Camel-riding Bedouins crossed the Euphrates around the same time, resisted only by the sheep-herding tribes that were already there. Villagers, beset by raids, deserted their homes and gave up their fields. The “desert line” in Syria moved steadily west as abandoned villages came to outnumber inhabited ones.

The last walls in either Western or Central Asia were anything but great. They were proof, reduced to the absurd, of the thesis that where there are no border walls, there will be city walls, and where there are no city walls, there will be neighborhood walls, and where there are no neighborhood walls, there will be walls of an even smaller sort. In the nineteenth century, Turkish tribesmen still hunted Persians to be captured and sold as slaves. The whole of Iran was soon dotted with “Turkoman towers,” into whose tiny openings Persian villagers crawled to escape Turkish slave raiders. The great walls had been reduced to the pathetic. But the Persians can hardly be faulted for the small scale of their efforts. There was, by then, little point in attempting to re-create a lost world of securely walled cities. That world was gone forever, not simply in Persia but everywhere, ruined by a new type of military technology that rendered almost every sort of wall obsolete.