As I approach the finish of this book—with new border walls being constructed or proposed all around the world even as I type—a fear nags at me: I can’t help but wonder if the fate of Peter Wyden might soon be mine. A former Newsweek correspondent, Wyden spent more than four years interviewing eyewitnesses and scouring written sources for his narrative history of the Berlin Wall. When he was done, the finished product ran a magnificent 762 pages. He finished just in time for Simon & Schuster to release Wall in late 1989. It was obsolete almost before it hit the shelves.

Wyden had assembled a meticulous history, but how could he have known what was about to happen—that the Wall’s spectacular climax would occur in the penultimate month of 1989, televised live around the world on MTV? He’d wrapped up his opus on a curiously subdued note. Life, he observed, had grown up around the Berlin Wall like weeds on an ancient ruin. West German families held picnics in the shade of the Wall, enjoying the lack of traffic; joggers raved about how pleasant it was to run alongside the concrete barrier; cabdrivers were bored of taking questions about it from tourists. “What have we learned from the Wall?” Wyden asked. “Not a great deal.”

In his conclusion, Wyden quoted a retired American official, a veteran of the Kennedy administration, ruefully recalling the lethargic Western response to the news that the first coils of barbed wire had been rolled out across the streets of the city in August 1961. “Nobody thought for a minute it would be permanent,” the official recalled. At the time of his statement in the late 1980s, the official could hardly envision a world without the Berlin Wall.

Of course, the Wall wasn’t permanent, and neither is anything else. The Mesopotamians, watching their mud-brick walls repeatedly wash away, had figured out that much four thousand years earlier. They concluded that even humans were made of clay and that when we die, we simply return to clay, sinking back into the ground, as if repaying a loan from the earth. Berlin’s infamous concrete barriers, like the great walls of Mesopotamia, gave only the illusion of permanence. If the American official had waited just a bit longer before giving his interview, he might have felt less disappointed by the Kennedy administration’s obtuseness back in August 1961. The Wall had proven temporary after all. It had just required a little more patience than anticipated.

But patience was every bit as elusive as permanence in those atom-obsessed days, and the Cold War was a time of bomb shelters and duck-and-cover drills, when news magazines still regularly enumerated the strengths of the two superpowers, laid out in colorful graphics, detailing the numbers of soldiers, airplanes, missiles, and warheads. In such an atmosphere, it was inconceivable that all we had to do was wait, that the Wall, and indeed the Cold War itself, would prove to be brief and historically insignificant. We still wrestle with that reality today. A hundred years from now, the Berlin Wall will be forgotten, as obscure as Shulgi’s Wall of the Land or the fortified lines of czarist Russia. The number of those who remember watching the Wall fall on MTV grows smaller every year. The number of those who once lived behind the Wall is smaller still. Future generations may wonder what all the hubbub was about.

For the time being, however, the Wall refuses to subside into the clay. It has firmly attached itself to our historical memory. In modern debates on walls, the Berlin Wall figures in almost every utterance. It is the universal example, perpetually at hand, perpetually tossed into discussions of barriers with which it had absolutely nothing in common. In its afterlife, it has assumed an importance out of proportion to its reality.

The story of the Berlin Wall turns out not at all what we expected it to be. It retains its gripping elements of international diplomacy, nuclear brinkmanship, fatal miscalculations, and brave escapes. However, the great players rarely seem in control. Seizing the narrative from them are the journalists, filmmakers, and news correspondents. The storytellers themselves have become bigger than the story, converting concrete and barbed wire into a symbol of such power that it has affected us ever since. They have played God with the Wall and with it our imaginations.

* * *

The preconditions for the Berlin Wall developed in the last months of World War II, when natural enemies who’d been made allies by the necessity of defeating Hitler met awkwardly at conferences to coordinate their final offensives. The Race to Berlin was no real race at all. The Soviets gobbled up great swaths of territory in their drive to dominate postwar Europe. Eisenhower, heedless of Churchill’s plea to advance quickly to “shake hands with the Russians as far East as possible,” took a more measured approach. In Eisenhower’s thinking, there was little to be gained by seizing territory that Roosevelt had already promised to the Russians. Germany was to be divided, and the Supreme Allied Commander wasn’t about to start a third world war by overrunning the Soviet sector.

A million and a half Berliners died during the war. No sooner had it ended than the survivors endured the systematic looting of their industrial base, as the Soviets—for a while the sole occupiers of the German capital—shipped nearly all the city’s heavy equipment to Russia. By the time US and British troops arrived to assume their role in administering the former capital, the bombed-out city could no longer feed itself.

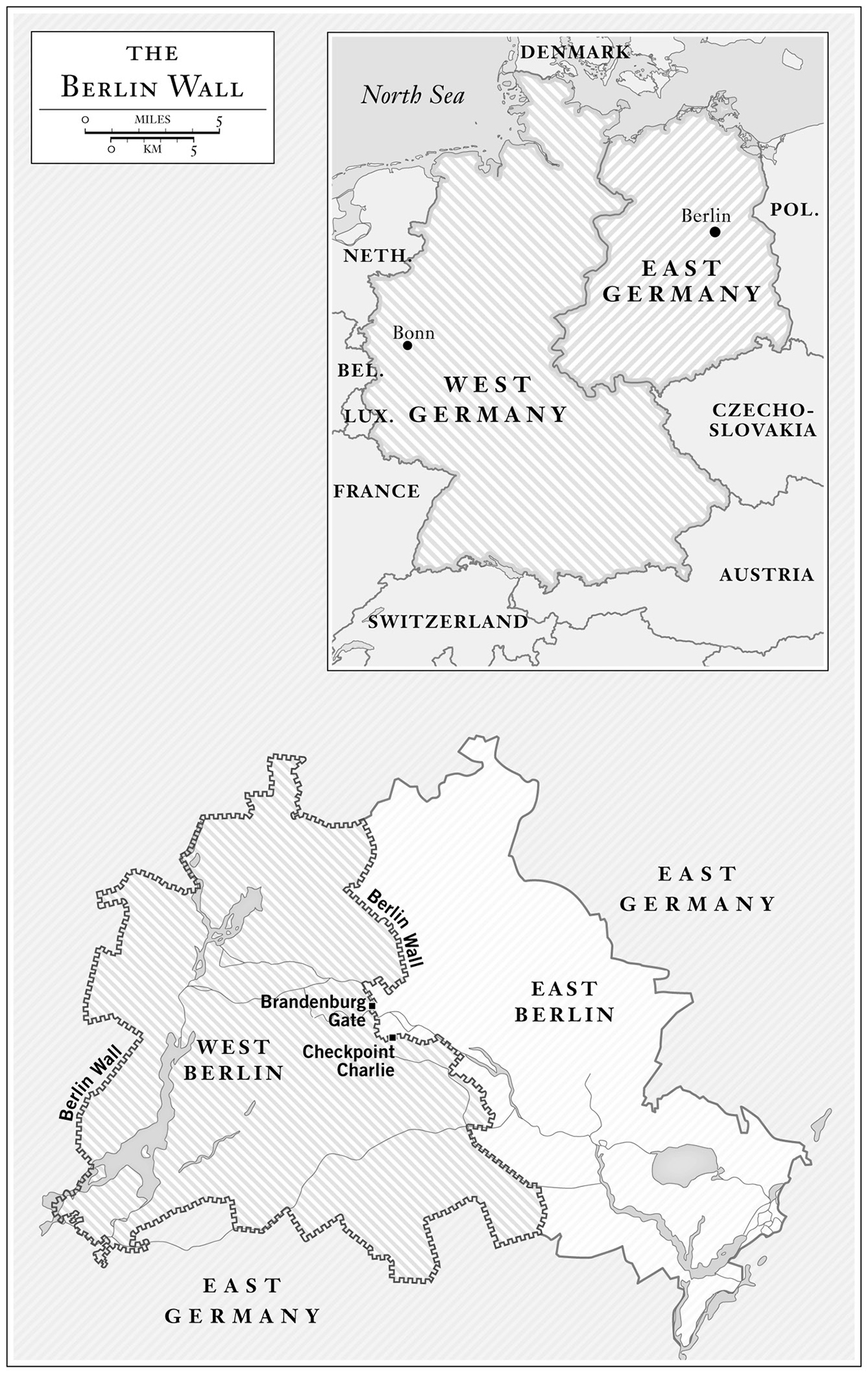

In the tug-of-war over Berlin, the Cold War commenced almost immediately. Wartime treaties had already determined the city’s future: Berlin was to be divided into four sectors, with the British, French, Americans, and Russians each administering one. In accordance with the agreements, all of Berlin—even the Western sectors—lay deep in Soviet-controlled East Germany. It was an impossible design, all but guaranteeing friction.

In writing about Cold War Berlin, I’m probably not the first author to recall the story in which the biblical King Solomon is said to have resolved a maternity dispute by ordering a baby split in half. He averted the actual tragedy by swiftly awarding the child to the woman who objected most strenuously to his plan. In the case of Berlin, the baby died. In 1946, the Russians vetoed Berlin’s first free elections since the days before Hitler. Two years later, they adopted a more extreme strategy, attempting to starve the allies out of Berlin. The Berlin blockade could well have sparked a war, if the Western powers hadn’t been so sick of fighting. For nearly a year, the American-, French-, and British-controlled areas subsisted as an island, supplied only by air. A new city—West Berlin—was born.

The bifurcated city occupied a unique position in Cold War Europe. It was the most vulnerable point in both the Eastern and Western systems. To Nikita Khrushchev, the bombastic Soviet premier who succeeded Stalin, Berlin was “the testicles of the West.” He needed only to squeeze them from time to time to make the West howl. But Berlin was equally problematic for Khrushchev and, before him, Stalin. The realization that the Russians intended to lay permanent claim to Eastern Europe horrified those who recalled the scourge of Communist political violence in the twenties and thirties. Hundreds of thousands of East Germans fled west. Within a year, more than a million had made their escape. Stalin, having looted East Germany of its industrial capital, now saw it looted of its human capital. Forced to deal with an exodus that threatened to hollow out the Soviet zones altogether, he finally turned to an ancient strategy, twisting it toward a new and perverted end.

* * *

It is a measure of the hold that the Berlin Wall still has on our imaginations that few people today—and indeed even few specialists outside the affected countries—are aware that much longer Cold War walls preceded the enclosure of West Berlin. The curtain that separated East and West Germany was not, for the most part, iron, but close enough. It consisted of 870 miles of concrete, barbed wire, trip alarms, guard towers, and electric fencing. Similar barriers separated Hungary and Austria. The Iron Curtain evolved rapidly during the Cold War, but it was always a tangible, physical barrier. By the end, it had attained a form that now serves as the prototype for many of the controversial border walls of the twenty-first century.

The walls of the Iron Curtain preceded the Berlin Wall by more than a decade. On December 1, 1946, East German border police established roadblocks and barbed-wire fences between East and West Germany. Stalin took additional steps toward concretizing Cold War borders in May 1952. By 1959, the border was manned by tens of thousands of border police stationed in concrete guard towers. Local patrols augmented those of the feared East German secret police, the Stasi. Neighbors were encouraged to report on neighbors.

The early Iron Curtain had one gaping hole. In Berlin, where East and West still freely comingled, it was still quite easy for an Easterner to apply for freedom. The more formidable the border walls became, the more people took advantage of this last remaining opening. By 1961, the number of escapees had surpassed 4 million, and the figure would have been even higher had the West Germans not regularly tested the refugees and returned those deemed less desirable. Fewer and fewer skilled workers remained in the East, where the exodus exacerbated economic hardship. The Russians sold more than fifty tons of gold to prop up their tottering East German satellite, but no amount of cash could slow the tide of émigrés.

In late 1958, a frustrated Khrushchev squeezed “the testicles of the West” with fury. He demanded the Western powers withdraw from Berlin altogether, threatening to sign a separate treaty with East Germany that would essentially allow Russia to control all access to West Berlin. In the tense atmosphere of the atomic age, this was widely viewed as a threat of nuclear war. The crisis, however, passed without escalation.

Three years later, confronted by an unproven, young US president and dealing with a worsening emigration crisis, Khrushchev renewed his threats. The first year of the Kennedy administration had raised Cold War tensions to a new peak. Kennedy’s attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro with the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion had left the impression that the inexperienced president was not up to his task. While the hot-tempered Khrushchev contemplated the humiliation of his American counterpart, Walter Ulbricht, the squeaky-voiced and notoriously friendless leader of East Germany, pressed for a resolution to the emigration crisis. A lifelong Communist ideologue who wore his beard in the style of Lenin, Ulbricht frequently played the devil on Khrushchev’s shoulder, whispering into the Soviet premier’s ear plans that could potentially provoke nuclear war. Ulbricht dreamed of starving West Berlin into submission by severing all access to the city. He proposed clogging the air above West Berlin’s airport with giant balloons and jamming the channels used by the flight controllers. He also made plans to imprison West Berlin with walls.

* * *

In March 1961, Ulbricht ordered his trusted deputy Erich Honecker to stockpile barbed wire and concrete slabs in preparation for the construction of a massive barrier around West Berlin. Like Ulbricht a committed ideologue, Honecker had joined his first Communist youth organization at the age of ten, and his entire education had been acquired at Communist institutions such as the International Lenin School in Moscow. He’d envisioned walls around West Berlin since at least 1953, when reports of Communist youths fleeing the country in the aftermath of a worker’s revolt had shaken him.

The summer of 1961 brought a gradual escalation of tensions. A June meeting between Kennedy and Khrushchev left the American leader shaken. “He beat the hell out of me,” Kennedy confessed. In the aftermath of the summit, Khrushchev spoke openly of “freeing” West Berlin, and Ulbricht expressed his desire to strangle the Western enclave. Nuclear war seemed closer than it had ever been.

Kennedy addressed the crisis in a televised address on July 25. “We cannot and will not permit the Communists to drive us out of Berlin, either gradually or by force,” he declared. Khrushchev—having to consult a written transcript of Kennedy’s address in this last year before Telstar made satellite broadcasts possible—flew into a rage. With characteristic intemperance, he threatened a US diplomat with a “thermonuclear” response. A week later, he convened a meeting of Warsaw Pact leaders at the Kremlin.

While Western intelligence fished for news from that August 3–5 Warsaw Pact meeting, the future of Berlin was being decided in Moscow. Unbeknown to the CIA, Khrushchev rejected Ulbricht’s more inflammatory proposals. The East German leader succeeded in attaining only one concession: Khrushchev would allow him to seal West Berlin with barbed wire. The wire barrier would subsequently be transformed into a proper wall while the West, in Khrushchev’s words, would “stand there like dumb sheep.”

* * *

Ulbricht and Honecker had planned for this moment in strict secrecy. Berlin in 1961 was one of the most compromised cities of the Cold War, crawling with CIA agents who could still freely cross the border. East German leaders had taken to communicating only orally or in handwritten notes, all of which came from the hand of the same police colonel.

On the evening of August 12, Willy Brandt, the mayor of West Germany, gave a campaign speech in which he addressed the refugee issue. “They fear being shut into an enormous prison,” he said. That prophecy was just hours from being realized.

At midnight, August 13, 1961, a Sunday, Honecker phoned the army with a terse command: “You know the assignment! March!” Trucks roared alive and rumbled around the streets and countryside surrounding West Berlin. East German soldiers and police hammered fence posts into the ground and began stringing up fencing. They rolled out miles of barbed wire. At the famous Brandenburg Gate, where Napoleon had once marched into the city, workers jackhammered the street that had only hours earlier permitted routine border crossing by commuters and shoppers.

The shock was most keenly felt by those who had been living in denial. In the final days before Barbed Wire Sunday, many East Germans had sensed something was afoot. Observing the hasty deployment of police units, they had calculated daily, even hourly, whether the time had come to make their dash. Thirty thousand had escaped in July and another twenty-two thousand in early August. On the last day before the unrolling of the barbed wire, more than twenty-five hundred escaped. Now the procrastinators had run out of time. The clanging and roar of construction machinery roused a sleepy Berlin. In the middle of the night, panicked East Berliners hastily dressed themselves and embarked on belated and mostly doomed bids for freedom. Hundreds thronged the Friedrichstrasse Station, desperately trying to board trains that would never leave. At Bernauer Strasse, where the facades of apartment buildings still marked the border, East Berliners leaped from their windows to the Western streets below.

Desperation turned quickly to hysteria. “The West Is Doing Nothing!” blared the headline of the West German tabloid Bild. Within days, Berlin had been blanketed by posters comparing Western inactivity to the betrayal of Czechoslovakia at the Munich Conference of 1938. Thirty thousand West Berliners took to the streets in demonstrations.

* * *

The event that so many Berliners viewed as the brink of apocalypse engendered little initial response from the West. The next morning, the New York Times reported the events of Barbed Wire Sunday with a sleepy notice about commuting being shut down in Berlin. US secretary of state Dean Rusk gave the matter little attention in his midmorning briefing. That afternoon, he attended a baseball game. Harold Macmillan, the prime minister of England, carried on with a hunting trip.

Incredibly, the birth of the Berlin Wall had passed nearly unnoticed in Washington. Years later, Wyden would observe that few of the president’s top advisers even remembered the event:

They hardly remembered what they did on Sunday, August 13, 1961. Nor did they make records of that historic day, and I refer to such busy note-takers as McGeorge Bundy, Ted Sorensen, Arthur Schlesinger, Pierre Salinger, and Maxwell Taylor. Walt Rostow, in charge of the National Security Council that day, showed me his appointment book; to his consternation, it was blank.

For his part, the president actually welcomed the barbed wire, viewing it as the end of the Berlin crisis. In his opinion, the other side had blinked, and as he put it, “A wall is a hell of a lot better than a war.”

A wall is, by almost any measure, a hell of a lot better than a war—especially war of the thermonuclear variety—but Kennedy’s levelheaded judgment never gained much support. The storytellers had had quite enough calm. They were about to seize control of the narrative, and not for the last time the Berlin Wall would be made a symbol of far larger issues.

* * *

American journalists were the first to recalibrate the initial Western assessment. The presence of Western correspondents in Berlin—eyewitnesses to the hysteria—created an unprecedented opportunity for sensationalism. By sheer chance, David Brinkley had filmed the chaotic scenes at both the Friedrichstrasse Station and Bernauer Strasse. The old warhorse Edward R. Murrow, who had once broadcast the Battle of Britain over radio and who knew a thing or two about dramatizing a crisis, was also present. In his new capacity as head of the US Information Agency, he pounded the table for the Kennedy administration to respond to “the bottling up of a whole nation.” On Monday, August 14, Daniel Schorr of CBS watched the first concrete slabs being lowered into place. Describing the scene for cameras, he compared the new Berlin Wall to the infamous barrier the Nazis had once erected around the Warsaw Ghetto. All these reports were now winging their way back to the United States in canisters of film and tape that had been tossed into orange bags and loaded onto transatlantic airliners. The press had found its symbol, and it would soon be adopted by politicians and producers in every media.

The Berlin Wall achieved instant celebrity—printed, radioed, and broadcast into the hearts of audiences all over the Western world. Almost immediately, publishers rushed out coffee-table books with titles such as Barbed Wire Around Berlin. Adventure books followed, narrating heroic escapes in breathless detail. Fiction authors rushed out spy novels set against the stark background of the Wall. The Saturday Evening Post and the New Yorker ran features on it.

Television found the Wall especially irresistible. Against the objections of an embarrassed Kennedy administration, both CBS and NBC financed the digging of tunnels in exchange for exclusive film rights to the escapes. CBS eventually caved to pressure and dropped their project, although they did produce a fictional version, “Tunnel to Freedom,” which aired as an episode of the popular Armstrong Circle Theater. NBC’s enterprise carried on as planned. Twenty-nine East Germans escaped through the 150-yard tunnel before it was discovered and shut down. The resulting documentary dominated nightly ratings.

In California, a middle-aged actor watched such reports with interest. His Hollywood career all but over, he’d already commenced that inevitable transition when, midlife, a man’s view of the world turns inevitably more critical and dyspeptic, his ambitions focus less on comfort than position, and his interests narrow increasingly to the political. To Ronald Reagan, the Berlin Wall was a burning symbol of the Communist ideology he viewed as the immediate threat to the American way of life. Two decades later he would play a small but highly visible role—the most famous of his career—in bringing down the Wall. Meanwhile, the Hollywood establishment that had generally lost interest in Reagan was also taking a keen interest in the Wall.

The first director to deal with the Berlin Wall had a decidedly personal beef. Billy Wilder, already famous for Double Indemnity, Sunset Boulevard, and Some Like It Hot, was in Berlin filming the forgettable Cold War comedy One, Two, Three on Barbed Wire Sunday. The sudden change of conditions forced him to relocate production to Munich. Four months later, the movie debuted with a preface, written by the famously apolitical director and narrated by the film’s star, James Cagney:

On Sunday, August 13, 1961, the eyes of America were on the nation’s capital, where Roger Maris was hitting home runs #44 and 45 against the Senators. On that same day, without any warning, the East German Communists sealed off the border between East and West Berlin. I only mention this to show the kind of people we’re dealing with—real shifty.

This was only Hollywood’s first salvo. Dozens followed. Within a year of Barbed Wire Sunday, MGM had rushed out Escape from East Berlin (aka Tunnel 28), based on a breakout that had occurred in January of that year. The film premiered at a festive opening in West Berlin. British studios, having already warmed up with such pre-Wall Iron Curtain films as Beyond the Curtain, embraced the genre as well. In 1965, Britain’s Salem Films turned the John le Carré thriller The Spy Who Came in from the Cold into a film featuring Richard Burton. By then, images of Berlin were already so familiar that the movie’s opening images required no narration; the audience was expected to recognize the Wall immediately. From that point on, Berlin Wall movies became something of a staple. The next year alone brought Funeral in Berlin, starring Michael Caine in an adaptation of Len Deighton’s spy novel, as well as Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain, which starred Paul Newman. By 1972, even the Philippines had produced its first Berlin Wall movie—Escape from East Berlin—featuring dialog in Tagalog.

As movies and television lavished attention on Cold War Berlin, the Wall became a must-see for foreign travelers. Western tourists who might otherwise have skipped Berlin altogether now made pilgrimages to the Wall. As early as 1962, exasperated Berliners were already complaining about the parade of tour buses. Meanwhile, the Wall continued to evolve. By the 1970s, the famous concrete slabs, covered in graffiti, represented only the outermost portion of a barrier system that was mostly hidden from Western eyes. Given a bird’s-eye view, tourists could have seen that behind the Wall lay a death zone that included beds of raised nails, booby traps, land mines, and barbed wire. The Western side—and let us not forget that the Wall technically enclosed West Berlin, not East—was considerably more approachable. Kids played by it, and neighborhood families held parties in its shade. Tourists were mostly routed to the Potsdamer Platz, where street vendors hawked sausages and souvenirs, and guides recited stories of harrowing escapes. In 1978, a particularly famous pair of Americans arrived: Ronald and Nancy Reagan, accompanied by a television crew, just months before the launch of Reagan’s successful presidential campaign.

By the time Reagan made his famous demand that the barrier be torn down, the Berlin Wall had been trotted across Western pages and screens for over two decades. Shock had gradually turned to familiarity and then something else again. As late as 1981, the Wall, by then somewhat typecast, was still starring in the tense made-for-TV thriller Berlin Tunnel 21, which featured a dramatic reenactment of Barbed Wire Sunday. But audiences were growing tired. In the mid-eighties, the once-chilling symbol of Communism had been reduced to a bit part in the spy comedy Gotcha! Somewhere between the quiet command of Richard Burton and the stammering of Anthony Edwards in Gotcha! the Wall had reached the end of its practical life span as a symbol of terror.

* * *

Long before Reagan’s demand that he “tear down this wall,” Mikhail Gorbachev had been laying the groundwork for just that. In the final chapter of the Wall’s history, Gorbachev was the one indispensable figure. Made leader of the Soviet Union in 1985, he quickly introduced reforms. In Russia, he liberated political prisoners, allowed open elections, and introduced market-based economic reforms. He also repudiated the so-called Brezhnev Doctrine, which had reserved for the Soviet Union the right to intervene in the affairs of any Soviet Bloc state. In Poland, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania, Soviet-supported dictators realized that they could no longer count on Russian support. In East Germany, Erich Honecker—who’d once been whisked to safety and saved by Soviet tanks during the workers’ revolt of 1953—unhappily confronted the same realization.

East Germany had fared poorly behind the Iron Curtain. Lost in so many daring escapes were many of the nation’s best—the risk takers, the problem solvers, the freethinkers, and the creators. They were the sort who persevered at difficult tasks until they’d completed long tunnels or fashioned homemade hot-air balloons. In the annals of the escapes, one searches in vain for escapees motivated by materialism, economic need, or a lust for Western goods. They came West seeking only freedom, fleeing a regime where propagandists controlled both the media and the schools. German reviewers excoriated Tunnel 28 because it depicted refugees fleeing simply to experience the material culture of the West. Now Gorbachev’s reforms threatened to undermine the East German leaders who’d clung to power partly by driving such creative people out.

The first changes occurred quietly, far from Honecker’s Berlin, on the border of Hungary and Austria. There, a state-of-the-art border-security system had gradually fallen into disrepair, a victim of the struggling Communist economy’s inability to cover the costs of maintenance. Electrified wires rusted and malfunctioned. Rabbits and birds set off thousands of costly false alarms. In 1988, the Hungarian government deemed its stretch of Iron Curtain too expensive. On May 2, 1989, with Gorbachev’s approval, the Hungarians announced their intention to dismantle their border wall.

Western leaders, conditioned for more than a quarter century to believe that only one wall mattered, responded predictably. “Let Berlin be next,” said President George H. W. Bush. The books, the documentaries, and the movies had always focused solely on the divided city. Who wanted to be known as the president who brought down the Austria-Hungary border fence?

In Eastern Europe, however, where the walls were something more than mere narrative, the Hungarian announcement was electrifying. East German tourists already in Hungary refused to vacate their campgrounds. Thousands crowded the West German embassy at Budapest, seeking asylum and escape. When the number of refugees overwhelmed the embassy, the Holy Family Roman Catholic Church began taking them in. The dreaded East German secret police were in Budapest all along, observing the asylum seekers from the roofs of nearby buildings, but they could only watch impotently as the encampments swelled by the thousands.

That August, a conservative Hungarian party received permission from the government to open the gates of the still-standing, still-guarded border so that a small crowd of Austrians and Hungarians could mingle for a few hours and celebrate the historic ties between their countries. The crowd that arrived for the picnic in Sopron stunned both the event organizers and the local border guards. In command of the Hungarian guards that day was Lieutenant Colonel Arpad Bella, pulling a Saturday shift on his wedding anniversary. Bella had been briefed to expect only a small ceremonial event. He was completely unaware that the decisions that would be forced on him would someday make him a minor celebrity, still sought out for interviews decades later.

A quarter century after the event there is no shortage of politicians eager to claim responsibility for what became known as the Pan-European Picnic. Bella’s account has at least remained consistent. As throngs of East German asylum seekers approached the gate, the Hungarian officer elected to ignore standing orders to fire a warning shot. His friend and counterpart on the Austrian side of the border, Johann Götl, was apoplectic. “Are you out of your mind?” he shouted. “We already discussed this, and then you send me six hundred people out of a cornfield!”

Hungary’s leaders were now racing to catch up to the forces they had inadvertently unleashed. For the next several weeks, they continued to police their still unopened borders, fearful that they had undermined the position of Gorbachev. Hungary’s prime minister, Miklós Németh, met with West Germany’s chancellor, Helmut Kohl, and agreed to bus the remaining refugees to West Germany. Within six weeks, nearly thirty thousand East Germans had escaped through Hungary, and the exodus only accelerated when Czechoslovakia opened its borders as well. By early October, some twelve thousand East Germans were camped out on the grounds of the German embassy at the baroque Lobkowicz Palace in Prague. Honecker, losing his grip, responded by closing East Germany’s borders even against other Soviet states, but the move came too late. Freedom was in the air—literally, in the form of former Knight Rider (and later Baywatch) star David Hasselhoff’s reissue of a seventies-era German pop song, which had been given new lyrics and retitled “Looking for Freedom.” Hasselhoff’s singing was, to be sure, an acquired taste, but the song held the top place on the charts for eight weeks and prompted a summer concert tour in which the singer drove a car through a mock Berlin Wall. Bootleg copies of the hit circulated around the East, providing the peppy earworm of the revolution.

By mid-autumn, the demonstrations had spread to East Germany. The crowds in Leipzig swelled ominously that October—first to 70,000, then 120,000, then 300,000. Erich Honecker, the architect of the Wall, who had just that January declared defiantly that the Wall would last another “fifty or one hundred years,” resigned under pressure from his party. On November 4, some half million protesters flooded the streets of Berlin. Five days later, it was all over.

* * *

Fittingly, the Wall, which had starred in so many books and movies over the years, saved its most memorable performance for last. On November 9, the media spokesman for East Berlin’s Communist Party read an obtuse policy announcement on new border regulations established by the politburo. A roomful of journalists pressed for clarification, none of them certain of the announcement’s meaning. Hours later, an Associated Press summary attempted to put the announcement in more straightforward terms: “The GDR is opening its borders.” This was probably not at all what the government intended, but it did have the effect of rendering the government’s intention’s moot, and the reality of a new era struck East Germans when they tuned in to the evening news. The response was electric. East Berliners poured out of their homes, crowding the still-closed gates. Crowds formed at every checkpoint, demanding to cross. Initially, the guards allowed only the more boisterous individuals through, and only after checking their documents. This created bottlenecks, frustrating the crowds even more. By 10:00 p.m., Egon Krenz, Honecker’s successor, knew that there was little he could do to reverse the damage from the AP story except to call out the tanks.

The nightly news broadcasts only worsened the government’s position, announcing that “the gates of the Wall stand wide-open.” This declaration was no more accurate than the AP report, but the words nevertheless galvanized the people. Was anyone still asleep in Berlin? It would hardly seem possible, judging from the crowds that streamed into the streets. The only Berliners left inside were the tank crews.

At 11:30 p.m., one of the Wall’s guard units, at a loss for orders and fearing it was about to lose control, opened the first checkpoint. By midnight, every checkpoint along the Wall had been thrown open. Exuberant youths scaled the Wall and chiseled off chunks of concrete. Across the seas, stunned Americans watched the fall of the monument whose rise, twenty-eight years earlier, had found them sleepy and oblivious. MTV broadcast the scene free and unencrypted to the newly popular satellite systems located around the world, especially in those areas not yet reached by cable.

* * *

In retrospect, the life of the Berlin Wall seems oddly short, a time span unbefitting a monument so thoroughly ingrained in our consciousness. The rest of the Iron Curtain was dismantled without fanfare. Local museums commemorate the old barriers. In Germany, an elongated green space has taken the place of the old Inner German border. Outside of those living in the immediate neighborhoods, few now recall that those barriers even existed. Our selective amnesia is embarrassing. The Western specialists in modern Eastern European history with whom I consulted were all entirely unaware of the physical barriers that once made up the Iron Curtain. But Berlin? They knew all about Berlin.

The Berlin Wall had always hogged the stage. When the Cold War died an unexpected death, the city held a spectacular wake, then the mourners all separated and went off to the only real business of the nineties: making money. A single relic—the star of books, tabloids, and movies—lingered behind, clinging to the spotlight like a fading diva, loath to relinquish her celebrity.

Lucky tourists carried off chunks of the Wall to display to their friends. Bill Roedy, the head of MTV Networks International, recalls carting off “suitcases and suitcases” of Wall fragments, later stamped with MTV’s logo and given away. Larger sections of the Wall were sold at auction to be displayed in the homes of wealthy buyers. Rock stars descended on Berlin to host me-too concerts. The English rock band Pink Floyd even emulated the Hasselhoff wall-busting stunt. Hasselhoff himself made a triumphant return.

Once the initial buzz had subsided, it might have seemed that the Berlin Wall would go the way of Ozymandias. Television specials on the Wall were ratings poison. And one can only imagine how quickly the rich must have tired of displaying dirty concrete slabs in their living rooms. Meanwhile, the movies and the novels of the Cold War faded into oblivion. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, Funeral in Berlin, and Torn Curtain only rarely resurface on cable nowadays, invariably seeming quaint and dated. The last VHS copies of Gotcha! went unsold at yard sales. Two thousand years from now, archaeologists sifting through our trash will perhaps find copies of it. With any luck, they’ll lack the technology to play it. Meanwhile, newsmagazines have stopped running infographics on Soviet and American troop numbers. For a while, they were replaced by articles about “the End of History.”

Of course, the key to celebrity survival is always reinvention, and this would hold true in the case of Berlin. The first books written about the Wall after its fall still highlighted the usual features: its tense beginnings, the daring escapes across it, and so forth. However, Hollywood had moved on in search of fresher stories. Communism had collapsed. The two Germanies were united. Russia had opened a stock exchange. A world obsessed with its new electronic toys forgot about the Cold War. History wasn’t dead, just forgotten. The Wall shed its former role as a symbol of Communist oppression and acquired an entirely new image in a foggy-minded popular imagination that remembered the Wall but couldn’t quite recall who’d built it or why.

The Berlin Wall had always had impeccable timing—making its grand appearance at the height of the Cold War and bowing out in spectacular fashion to bring the Cold War to its conclusion. It would now embark on its second career with similar timeliness, returning to the stage as a symbol of all border walls, just as they were about to make a reappearance around the world.