History

THE ETRUSCANS, GREEKS & MYTH

THE ROMAN REPUBLIC

JULIUS CAESAR

AUGUSTUS & EMPIRE

POPES & EMPERORS

THE WONDER OF THE WORLD

FLOURISHING CITY-STATES

CAVOUR & THE BIRTH OF ITALY

FROM THE TRENCHES TO FASCISM

THE COLD WAR IN ITALY

THE BERLUSCONI ERA

TIMELINE

Few countries have been on such a roller-coaster ride as Italy. The Italian peninsula lay at the core of the Roman Empire; one of the world’s great monotheistic religions, Catholicism, has its headquarters in Rome; and it was largely the dynamic city-states of Italy that set the modern era in motion with the Renaissance. But Italy has known chaos and deep suffering, too. The rise of Europe’s nation-states from the 16th century left the divided Italian peninsula behind. Italian unity was won in blood, but many Italians have since lived in abject poverty, sparking great waves of migration. The economic miracle of the 1960s propelled Italy to the top league of wealthy Western countries but, since the mid-1990s, the country has wallowed in a mire of frustration. A sluggish economy (hit hard by the global slump that began in 2008), seemingly ineffective and squabbling government, widespread corruption and the continuing open sore of the Mafia continue to overshadow the country’s otherwise sunny disposition.

Return to beginning of chapter

THE ETRUSCANS, GREEKS & MYTH

Of the many tribes that emerged from the millennia of the Stone Ages in ancient Italy, the Etruscans dominated the peninsula by the 7th century BC. Etruria was based on city-states mostly concentrated between the Arno and Tiber rivers. Among them were Caere (modern-day Cerveteri), Tarquinii (Tarquinia), Veii (Veio), Perusia (Perugia), Volaterrae (Volterra) and Arretium (Arezzo). The name of their homeland is preserved in the name Tuscany, where the bulk of their settlements were (and still are) located.

Most of what we know of the Etruscan people has been deduced from artefacts and paintings unearthed at their burial sights, especially at Tarquinia, near Rome. Argument persists over whether the Etruscans had migrated from Asia Minor. They spoke a language that today has barely been deciphered. An energetic people, the Etruscans were redoubtable warriors and seamen, but lacked cohesion and discipline.

At home, the Etruscans farmed and mined metals. Their gods were numerous and they were forever trying to second-guess them and predict future events through such rituals as examining the livers of sacrificed animals. They were also quick to learn from others. Much of their artistic tradition (which comes to us in the form of tomb frescoes, statuary and pottery) was influenced by the Greeks.

Indeed, while the Etruscans dominated the centre of the peninsula, Greek traders settled in the south in the 8th century BC, setting up a series of independent city-states along the coast and in Sicily that together were known as Magna Graecia. They flourished until the 3rd century BC and the ruins of magnificent Doric temples in Italy’s south (at Paestum) and on Sicily (at Agrigento, Selinunte and Segesta) stand as testimony to the splendour of Greek civilisation in Italy.

Attempts by the Etruscans to conquer the Greek settlements failed and accelerated their decline. The death knell, however, would come from an unexpected source — the grubby but growing Latin town of Rome.

The origins of the town are shrouded in myth, which says it was founded by Romulus (who descended from Aeneas, a refugee from Troy whose mother was the goddess Venus) on 21 April 753 BC on the site where he and his brother, Remus, had been suckled by a she-wolf as orphan infants. Romulus later killed Remus and the settlement was named Rome after him. At some point, legend merges with history. Seven kings are said to have followed Romulus and at least three were historical Etruscan rulers. In 509 BC, disgruntled Latin nobles turfed the last of the Etruscan kings, Tarquinius Superbus, out of Rome after his predecessor, Servius Tullius, had stacked the Senate with his allies and introduced citizenship reforms that undermined the power of the aristocracy. Sick of monarchy, the nobles set up the republic. Over the following centuries, this piffling Latin town would grow to become Italy’s major power, gradually sweeping aside the Etruscans, whose language and culture had disappeared by the 2nd century AD.

Return to beginning of chapter

THE ROMAN REPUBLIC

Under the republic, imperium, or regal power, was placed in the hands of two consuls who acted as political and military leaders and were elected for nonrenewable one-year terms by an assembly of the people. The Senate, whose members were appointed for life, advised the consuls.

Although from the beginning monuments were emblazoned with the initials SPQR (Senatus Populusque Romanus, or the Senate and People of Rome), the ‘people’ initially had precious little say in affairs. (The initials are still used and many Romans would argue that little has changed.) Known as plebeians (literally ‘the many’), the disenfranchised majority slowly wrested concessions from the patrician class in the more than two centuries that followed the founding of the republic. Some plebs were even appointed as consuls and indeed by about 280 BC most of the distinctions between patricians and plebeians had disappeared. That said, the apparently democratic system was largely oligarchic, with a fairly narrow political class (whether patrician or plebeian) vying for positions of power in government and the Senate.

The Romans were a rough-and-ready lot. Rome did not bother to mint coins until 269 BC, even though the neighbouring (and later conquered or allied) Etruscans and Greeks had long had their own currencies. The Etruscans and Greeks also brought writing to the attention of Romans, who found it useful for documents and technical affairs but hardly glowed in the literature department. Eventually the Greek pantheon of gods formed the bedrock of Roman worship. Society was patriarchal and its prime building block the household (familia). The head of the family (pater familias) had direct control over his wife, children and extended family. He was responsible for his children’s education. Devotion to household gods was as strong as to the increasingly Greek-influenced pantheon of state gods, led at first by the triad of Jupiter (the sky god and chief protector of the state), Juno (the female equivalent of Jupiter and patron goddess of women) and Minerva (patron goddess of craftsmen). Mars, the god of war, had been replaced by Juno in the triad.

Slowly at first, then with gathering pace, Roman armies conquered the Italian peninsula. Defeated city-states were not taken over directly; rather they were obliged to become allies. They retained their government and lands but had to provide troops on demand to serve in the Roman army. This relatively light-handed touch was a key to success. Increasingly, the protection offered by Roman hegemony induced many cities to become allies voluntarily. Wars with rivals like Carthage and in the East led Rome to take control of Sardinia, Sicily, Corsica, mainland Greece, Spain, most of North Africa and part of Asia Minor by 133 BC.

By then, Rome was the most important city in the Mediterranean, with a population of 300,000. Most were lower-class freedmen or slaves living in often precarious conditions. Tenement housing blocks (mostly of brick and wood) were raised alongside vast monuments. One of the latter was the Circus Flaminius, stage of some of the spectacular games held each year. These became increasingly important events for the people of Rome, who flocked to see gladiators and wild beasts in combat.

Return to beginning of chapter

JULIUS CAESAR

Born in 100 BC, Gaius Julius Caesar would prove to be one of Rome’s most masterful generals, lenient conquerors and capable administrators. He was also avid for power and this was probably his undoing.

He was a supporter of the consul Pompey (later known as Pompey the Great), who since 78 BC had become a leading figure in Rome after putting down rebellions in Spain and eliminating piracy. Caesar himself had been in Spain for several years, dealing with border revolts, and on his return to Rome in 60 BC, formed an alliance with Pompey and another important commander and former consul, Crassus. They backed Caesar’s candidacy as consul.

To consolidate his position in the Roman power game, Caesar needed a major military command. This he received with a mandate to govern the province of Gallia Narbonensis, a southern swathe of modern France stretching from Italy to the Pyrenees, from 59 BC. Caesar raised troops and in the following year entered Gaul proper (modern France) to head off an invasion of Helvetic tribes from Switzerland and subsequently to bring other tribes to heel. What started as an essentially defensive effort soon became a full-blown campaign of conquest. In the next five years, he subdued Gaul and made forays into Britain and across the Rhine. In 52—51 BC he stamped out the last great revolt in Gaul, led by Vercingetorix. Caesar was generous to his defeated enemies and so won the Gauls over to him. Indeed, they became his staunchest supporters in coming years.

By now, Caesar also had a devoted veteran army behind him. Jealous of the growing power of his one-time protégé, Pompey severed his political alliance with him and joined like-minded factions in the Senate to outlaw Caesar in 49 BC. On 7 January, Caesar crossed the Rubicon river into Italy and civil war began. His three-year campaign in Italy, Spain and the Eastern Mediterranean proved a crushing victory. Upon his return to Rome in 46 BC, he assumed dictatorial powers.

He launched a series of reforms, overhauled the Senate and embarked on a building programme (of which the Curia, Click here, and Basilica Giulia, Click here, remain).

By 44 BC, it was clear Caesar had no plans to restore the Republic, and dissent grew in the Senate, even among former supporters like Marcus Junius Brutus who thought he had gone too far. Unconcerned by rumours of a possible assassination attempt, Caesar had dismissed his bodyguard. A small band of conspirators led by Brutus finally stabbed him to death in a Senate meeting on the Ides of March (15 March) 44 BC, two years after he had been proclaimed dictator for life.

In the years following Caesar’s death, his lieutenant, Mark Antony (Marcus Antonius), and nominated heir, great-nephew Octavian, plunged into civil war against Caesar’s assassins. Things calmed down as Octavian took control of the western half of the empire and Antony headed to the east, but when Antony fell head over heels for Cleopatra VII in 31 BC, Octavian went to war and finally claimed victory over Antony and Cleopatra at Actium, in Greece. The next year, Octavian invaded Egypt, Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide and Egypt became a province of Rome.

Return to beginning of chapter

AUGUSTUS & EMPIRE

Octavian was left as sole ruler of the Roman world and by 27 BC had been acclaimed Augustus (Your Eminence) and conceded virtually unlimited power by the Senate. In effect, he had become emperor.

Under him, the arts flourished. Augustus was lucky in having as his contemporaries the poets Virgil, Horace and Ovid, as well as the historian Livy. He encouraged the visual arts, restored existing buildings and constructed many new ones. During his reign the Pantheon was raised and he boasted that he had ‘found Rome in brick and left it in marble’.

The long period of comparatively enlightened rule that he initiated brought unprecedented prosperity and security to the Mediterranean. The Empire was, in the main, wisely administered (although there were some kooky exceptions, such as the potty Caligula).

By AD 100, the city of Rome is said to have had more than 1.5 million inhabitants and all the trappings of the imperial capital — its wealth and prosperity were obvious in the rich mosaics, marble temples, public baths, theatres, circuses and libraries. People of all races and conditions converged on the capital. Poverty was rife among an often disgruntled lower class. Augustus had created Rome’s first police force under a city prefect (praefectus urbi) to curb mob violence, which had long gone largely unchecked. He had also instituted a 7000-man fire brigade and night watchman service.

Augustus carried out other far-reaching reforms. He streamlined the army, which was kept at a standing total of around 300,000. Military service ranged from 16 to 25 years, but Augustus kept conscription to a minimum, making it a largely volunteer force. He consolidated Rome’s three-tier class society. The richest and most influential class remained the Senators. Below them, the so-called Equestrians filled posts in public administration and supplied officers to the army (control of which was essential to keeping Augustus’ position unchallenged). The bulk of the populace filled the ranks of the lower class. The system was by no means rigid and upward mobility was possible.

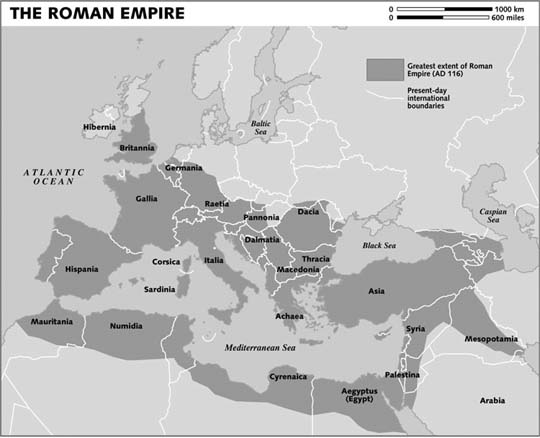

A century after Augustus’ death in AD 14 (aged 75), the Empire had reached its greatest extent. Under Hadrian (76—138), the Empire stretched from the Iberian peninsula, Gaul and Britain to a line that basically followed the Rhine and Danube rivers. All of the present-day Balkans and Greece, along with the areas known in those times as Dacia, Moesia and Thrace (considerable territories reaching to the Black Sea), were under Roman control. Most of modern-day Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Israel was occupied by Rome’s legions and linked up with Egypt. From there a deep strip of Roman territory stretched along the length of North Africa to the Atlantic coast of what is today northern Morocco. The Mediterranean was a Roman lake.

This situation lasted until the 3rd century. By the time Diocletian (245—305) became emperor, attacks on the Empire from without and revolts within had become part and parcel of imperial existence. A new religious force, Christianity, was gaining popularity and under Diocletian persecution of Christians became common, a policy reversed in 313 under Constantine I, who granted freedom of worship.

The Empire was later divided in two, with the second capital in Constantinople (founded by Constantine in 330), on the Bosporus in Byzantium. It was this, the eastern Empire, which survived as Italy and Rome were overrun. This rump empire stretched from parts of present-day Serbia and Montenegro across to Asia Minor, a coastal strip of what is now Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Israel down to Egypt and a sliver of North Africa as far west as modern Libya. Attempts by Justinian I (482—565) to recover Rome and the shattered western half of the Empire ultimately came to nothing.

Return to beginning of chapter

POPES & EMPERORS

In an odd twist, the minority religion that Emperor Diocletian had tried so hard to stamp out saved the glory of the city of Rome. Through the chaos of invasion and counter-invasion that saw Italy succumb to Germanic tribes, the Byzantine reconquest and the Lombard occupation in the north, the papacy established itself in Rome as a spiritual and secular force.

The popes were, even at this early stage, a canny crowd. The papacy invented the Donation of Constantine, a document in which Emperor Constantine I had supposedly granted the Church control of Rome and surrounding territory. What the popes needed was a guarantor with military clout. This they found in the Franks and a deal was done.

In return for formal recognition of the popes’ control of Rome and surrounding Byzantine-held territories henceforth to be known as the Papal States, the popes granted the Carolingian Franks a leading if ill-defined role in Italy and their king, Charlemagne, the title of Holy Roman Emperor. He was crowned by Leo III on Christmas Day 800. The bond between the papacy and the Byzantine Empire was thus broken and political power in what had been the Western Roman Empire shifted north of the Alps, where it would remain for more than 1000 years.

The stage was set for a future of seemingly endless struggles. Similarly, Rome’s aristocratic families engaged in battle for the papacy. For centuries, the imperial crown would be fought over ruthlessly and Italy would frequently be the prime battleground. Holy Roman Emperors would seek time and again to impose their control on increasingly independent-minded Italian cities, and even on Rome itself. In riposte, the popes continually sought to exploit their spiritual position to bring the emperors to heel and further their own secular ends.

The clash between Pope Gregory VII and Emperor Henry IV over who had the right to appoint bishops (who were powerful political players and hence important friends or dangerous foes) in the last quarter of the 11th century showed just how bitter these struggles could become. They became a focal point of Italian politics in the late Middle Ages and across the cities and regions of the peninsula two camps emerged: Guelphs (Guelfi, who backed the pope) and Ghibellines (Ghibellini, in support of the emperor).

Return to beginning of chapter

THE WONDER OF THE WORLD

The Holy Roman Empire had barely touched southern Italy until Henry, son of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I (Barbarossa), married Constance de Hauteville, heir to the Norman throne in Sicily. Of this match was born one of the most colourful figures of medieval Europe, Frederick II (1194—1250).

Crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 1220, Frederick was a German with a difference. Having grown up in southern Italy, he considered Sicily his natural base and left the German states largely to their own devices. A warrior and scholar, Frederick was an enlightened ruler with an absolutist vocation. A man who allowed freedom of worship to Muslims and Jews, he was not to everyone’s liking, as his ambition was to finally bring all of Italy under the imperial yoke.

A poet, linguist, mathematician, philosopher and all-round fine fellow, Frederick founded a university in Naples and encouraged the spread of learning and translation of Arab treatises. From his early days at the imperial helm, he was known as Stupor Mundi (the Wonder of the World) for his extraordinary talents, energy and military prowess.

Having reluctantly carried out a crusade (marked more by negotiation than the clash of arms) in the Holy Land in 1228—29 on pain of excommunication, Frederick returned to Italy to find Papal troops invading Neapolitan territory. Frederick soon had them on the run and turned his attention to gaining control of the complex web of city-states in central and northern Italy, where he found allies and many enemies, in particular the Lombard league. Years of inconclusive battles ensued, which even Frederick’s death in 1250 did not end. Several times he had been on the verge of taking Rome and victory had seemed assured more than once. Campaigning continued until 1268 under Frederick’s successors, Manfredi (who fell in the bloody Battle of Benevento in 1266) and Corradino (captured and executed two years later by French noble Charles of Anjou, who had by then taken over Sicily and southern Italy).

Return to beginning of chapter

FLOURISHING CITY-STATES

While the south of Italy tended to centralised rule, the north was heading the opposite way. Port cities such as Genoa, Pisa and especially Venice, along with internal centres such as Florence, Milan, Parma, Bologna, Padua, Verona and Modena, became increasingly insolent towards attempts by the Holy Roman Emperors to meddle in their affairs.

The cities’ growing prosperity and independence also brought them into conflict with Rome, which found itself increasingly incapable of exercising influence over them. Indeed, at times Rome’s control over some of its own Papal States was challenged. Caught between the papacy and the emperors, it was not surprising that these city-states were forever switching allegiances in an attempt to best serve their own interests.

Between the 12th and 14th centuries, they developed new forms of government. Venice adopted an oligarchic, ‘parliamentary’ system in an attempt at limited democracy. More commonly, the city-state created a comune (town council), a form of republican government dominated at first by aristocrats but then increasingly by the wealthy middle classes. The well-heeled families soon turned their attentions from business rivalry to political struggles, in which each aimed to gain control of the signoria (government).

In some cities, great dynasties, such as the Medici in Florence and the Visconti and Sforza in Milan, came to dominate their respective stages.

War between the city-states was a constant and eventually a few, notably Florence, Milan and Venice, emerged as regional powers and absorbed their neighbours. Their power was based on a mix of trade, industry and conquest. Constellations of power and alliances were in constant flux, making changes in the city-states’ fortunes the rule rather than the exception. Easily the most stable and long the most successful of them was Venice.

In Florence, prosperity was based on the wool trade, finance and general commerce. Abroad, its coinage, the firenze (florin), was king.

In Milan, the noble Visconti family destroyed its rivals and extended Milanese control over Pavia and Cremona, and later Genoa. Giangaleazzo Visconti (1351—1402) turned Milan from a city-state into a strong European power. The policies of the Visconti (up to 1450), followed by those of the Sforza family, allowed Milan to spread its power to the Ticino area of Switzerland and east to the Lago di Garda.

The Milanese sphere of influence butted up against that of Venice. By 1450 the lagoon city had reached the height of its territorial greatness. In addition to its possessions in Greece, Dalmatia and beyond, Venice had expanded inland. The banner of the Lion of St Mark flew across northeast Italy, from Gorizia to Bergamo.

These dynamic, independent-minded cities proved fertile ground for the intellectual and artistic explosion that would take place across northern Italy in the 14th and 15th centuries. After centuries of Church-dominated obscurantism, the arrival of eastern scholars fleeing Constantinople in the wake of its fall to the Ottoman Turkish Muslims in 1453 (marking the end of what had once been the Roman Empire), prompted a reawakening of interest in classical learning (the importance of human reason, as opposed to divine order), especially the works of Aristotle and Plato. This coincided with a burst of new and original artistic activity that would soon snowball into the wonders of the Renaissance (Click here). Of them all, Florence was the cradle and launch pad for this fevered activity, in no small measure due to the generous patronage of the long-ruling Medici family.

CAVOUR & THE BIRTH OF ITALY

The French Revolution at the end of the 18th century and the rise of Napoleon awakened hopes in Italy of independent nationhood. Since the glory days of the Renaissance, Italy’s divided mini-states had gradually lost power and status on the European stage. By the late 18th century, the peninsula was little more than a tired, backward playground for the big powers.

Napoleon marched into Italy on several occasions, finishing off the Venetian republic in 1797 (ending 1000 years of Venetian independence) and creating the so-called Kingdom of Italy in 1804. That kingdom was in no way independent but the Napoleonic earthquake spurred many Italians to believe that a single Italian state could be created after the emperor’s demise.

It was not to be so easy. The reactionary Congress of Vienna restored all the foreign rulers to their places in Italy.

Count Camillo Benso di Cavour (1810—61) of Turin, the prime minister of the Savoy monarchy, became the diplomatic brains behind the Italian unity movement. Through the pro-unity newspaper, Il Risorgimento (founded in 1847) and the publication of a parliamentary Statuto (Statute), Cavour and his colleagues laid the groundwork for unity.

Cavour conspired with the French and won British support for the creation of an independent Italian state. His 1858 treaty with France’s Napoleon III foresaw French aid in the event of a war with Austria and the creation of a northern Italian kingdom, in exchange for parts of Savoy and Nice.

The bloody Franco-Austrian War (also known as the war for Italian independence; 1859—61), unleashed in northern Italy, led to the occupation of Lombardy and the retreat of the Austrians to their eastern possessions in the Veneto. In the meantime, a wild card in the form of professional revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi had created the real chance of full Italian unity. Garibaldi took Sicily and southern Italy in a military blitz in the name of Savoy king Vittorio Emanuele II in 1860. Spotting the chance, Cavour and the king moved to take parts of central Italy (including Umbria and Le Marche) and so were able to proclaim the creation of a single Italian state in 1861.

In the following nine years, Tuscany, the Veneto and Rome were all incorporated into the fledgling kingdom. Unity was complete and parliament was established in Rome in 1871.

The turbulent new state saw violent swings between socialists and the right. Giovanni Giolitti, one of Italy’s longest-serving prime ministers (heading five governments between 1892 and 1921), managed to bridge the political extremes and institute male suffrage. Women were, however, denied the right to vote until after WWII.

Return to beginning of chapter

FROM THE TRENCHES TO FASCISM

When war broke out in Europe in July 1914, Italy chose to remain neutral despite being a member of the Triple Alliance with Austria and Germany. Italy had territorial claims on Austrian-controlled Trento (Trentino), southern Tyrol, Trieste and even in Dalmatia (some of which it had tried and failed to take during the Austro-Prussian war of 1866). Under the terms of the Triple Alliance, Austria was due to hand over much of this territory in the event of occupying other land in the Balkans, but Austria refused to contemplate fulfilling this part of the bargain.

The Italian government was divided between a non-interventionist and war party. The latter, in view of Austria’s intransigence, decided to deal with the Allies. In the London pact of April 1915, Italy was promised the territories it sought after victory. In May, Italy declared war on Austria and thus plunged into a 3½-year nightmare.

Italy and Austria engaged in a weary war of attrition. When the Austro-Hungarian forces collapsed in November 1918, the Italians marched into Trieste and Trento. The post-war Treaty of Versailles failed to award Rome the remaining territories it had sought.

These were slim pickings after such a bloody and exhausting conflict. Italy lost 600,000 men and the war economy had produced a small concentration of powerful industrial barons while leaving the bulk of the civilian populace in penury. This cocktail was made all the more explosive as hundreds of thousands of demobbed servicemen returned home or shifted around the country in search of work. The atmosphere was perfect for a demagogue. The demagogue was not long in coming forth.

One of the young war enthusiasts had been the socialist newspaper editor and one-time draft dodger, Benito Mussolini (1883—1945). This time he volunteered for the front and only returned, wounded, in 1917.

The experience of war and the frustration shared with many at the disappointing outcome in Versailles led him to form a right-wing militant political group that by 1921 had become the Fascist Party, with its black-shirted street brawlers and Roman salute. These were to become symbols of violent oppression and aggressive nationalism for the next 23 years. After his march on Rome in 1922 and victory in the 1924 elections, Mussolini (who called himself the Duce, or Leader) took full control of the country by 1926, banning other political parties, trade unions not affiliated to the party, and the free press.

By the 1930s, all aspects of Italian society were regulated by the party. The economy, banking, massive public works programmes, the conversion of coastal malarial swamps into arable land and an ambitious modernisation of the armed forces were all part of Mussolini’s grand plan.

On the international front, Mussolini at first showed a cautious hand, signing international cooperation pacts (including the 1928 Kellogg Pact solemnly renouncing war) and until 1935 moving close to France and the UK to contain the growing menace of Adolf Hitler’s rapidly re-arming Germany.

That all changed when Mussolini decided to invade Abyssinia (Ethiopia) as the first big step to creating a ‘new Roman empire’. This aggressive side of Mussolini’s policy had already led to skirmishes with Greece over the island of Corfu and to military expeditions against nationalist forces in the Italian colony of Libya.

The League of Nations condemned the Abyssinian adventure (King Vittorio Emanuele III was declared Emperor of Abyssinia in 1936) and from then on Mussolini changed course, drawing closer to Nazi Germany. They backed the rebel General Franco in the three-year Spanish Civil War and in 1939 signed an alliance pact.

WWII broke out in September 1939 with Hitler’s invasion of Poland. Italy remained aloof until June 1940, by which time Germany had overrun Norway, Denmark, the Low Countries and much of France. It seemed too easy and so Mussolini entered on Germany’s side in 1940, a move Hitler must have regretted later. Germany found itself pulling Italy’s chestnuts out of the fire in campaigns in the Balkans and North Africa and could not prevent Allied landings in Sicily in 1943.

By then, the Italians had had enough of Mussolini and his war and so the king had the dictator arrested. In September, Italy surrendered and the Germans, who had rescued Mussolini, occupied the northern two-thirds of the country and reinstalled the dictator.

The painfully slow Allied campaign up the peninsula and German repression led to the formation of the Resistance, which played a growing role in harassing German forces. Northern Italy was finally liberated in April 1945. Resistance fighters caught Mussolini as he fled north in the hope of reaching Switzerland. They shot him and his lover, Clara Petacci, before stringing up their corpses (along with others) in Milan’s Piazzale Lotto.

Return to beginning of chapter

THE COLD WAR IN ITALY

In the aftermath of war, the left-wing Resistance was disarmed and Italy’s political forces scrambled to regroup. The USA, through the economic largesse of the Marshall Plan, wielded considerable political influence and used this to keep the left in check.

Immediately after the war, three coalition governments succeeded one another. The third, which came to power in December 1945, was dominated by the newly formed right-wing Democrazia Cristiana (DC; Christian Democrats), led by Alcide de Gasperi, who remained prime minister until 1953. Italy became a republic in 1946 and De Gasperi’s DC won the first elections under the new constitution in 1948.

Until the 1980s, the Partito Comunista Italiano (PCI; Communist Party), at first under Palmiro Togliatti and later the charismatic Enrico Berlinguer, played a crucial role in Italy’s social and political development, in spite of being systematically kept out of government.

The very popularity of the party led to a grey period in the country’s history, the anni di piombo (years of lead) in the 1970s. Just as the Italian economy was booming, Europe-wide paranoia about the power of the Communists in Italy fuelled a secretive reaction that, it is said, was largely directed by the CIA and NATO. Even today, little is known about Operation Gladio, an underground paramilitary organisation supposedly behind various unexplained terror attacks in the country, apparently designed to create an atmosphere or fear in which, should the Communists come close to power, a right-wing coup could be quickly carried out.

The 1970s were thus dominated by the spectre of terrorism and considerable social unrest, especially in the universities. Neo-Fascist terrorists struck with a bomb blast in Milan in 1969. In 1978, the Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades, a group of young left-wing militants responsible for several bomb blasts and assassinations), claimed their most important victim — former DC prime minister Aldo Moro. His kidnap and (54 days later) murder (the subject of the 2004 film Buongiorno Notte) shook the country.

Despite the disquiet, the 1970s was also a time of positive change. In 1970, regional governments with limited powers were formed in 15 of the country’s 20 regions (the other five, Sicily, Sardinia, Valle d’Aosta, Trentino-Alto Adige and Friuli Venezia Giulia, already had strong autonomy statutes). In the same year, divorce became legal and eight years later abortion was also legalised, following anti-sexist legislation that allowed women to keep their own names after marriage.

Return to beginning of chapter

THE BERLUSCONI ERA

A growth spurt in the 1980s saw Italy become one of the world’s leading economies, but by the mid-1990s a new and prolonged period of crisis had set in. High unemployment and inflation, combined with a huge national debt and mercurial currency (the lira), led the government to introduce draconian measures to cut public spending, allowing Italy to join the single currency (euro) in 2001.

The old order seemed to crumble in the 1990s. The PCI split in two. The old guard minority, Partito della Rifondazione Comunista (PRC; Refounded Communist Party), was led by Fausto Bertinotti until crushing election defeat in 2008 (when it failed to reach the minimum 5% of the vote cut-off mark for entry to parliament). The bigger and moderate breakaway wing reformed itself as Democratici di Sinistra (DS; Left Democrats) and, in 2007, merged with another centre-left group to create the Partito Democratico (PD).

The rest of the Italian political scene was rocked by the Tangentopoli (‘kickback city’) scandal, which broke in Milan in 1992. Led by a pool of Milanese magistrates, including the tough Antonio di Pietro, investigations known as Mani Pulite (Clean Hands) implicated thousands of politicians, public officials and businesspeople in scandals ranging from bribery and receiving kickbacks to blatant theft.

The old centre-right political parties collapsed in the wake of these trials and from the ashes rose what many Italians hoped might be a breath of fresh political air. Media magnate Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia (Go Italy) party swept to power in 2001 and, after an inconclusive two-year interlude of centre-left government under former European Commission head Romano Prodi from 2006, again in April 2008.

Together with the right-wing (one-time Fascist) Alleanza Nazionale (National Alliance) under Gianfranco Fini and the polemical, separatist Lega Nord (Northern League), Berlusconi sits at the head of a coalition known as Popolo della Libertà (People of Liberty) with an unassailable majority.

Led by the former mayor of Rome, Walter Veltroni, the PD was unable to recover after winning only 38% of the vote in the 2008 elections. In quick succession, the PD was worsted in municipal elections around the country and regional polls in Friuli Venezia Giulia, Abruzzo and Sardinia. This latter defeat, in February 2009, led Veltroni to quit, leaving the chronically divided left in chaos.

From 2001 to 2006, Berlusconi’s rule was marked by a series of laws that protected his extensive business interests (he controls as much as 90% of the country’s free TV channels). He also spent considerable time hitting out against what he claimed to be the country’s ‘politicised’ judges. The latter have been looking into his myriad business affairs since the beginning of the 1990s, but one trial after another has collapsed.

One of Berlusconi’s first acts in 2008 was to resolve the long-standing garbage crisis in Naples. A complex issue dating to the early 1990s, garbage disposal bottlenecks have put Naples through several malodorous moments, with vast amounts of refuse piling up all over the city and its surrounding areas. Corruption, poor administration, overflowing rubbish dumps and controversy over where to locate incinerators have all contributed to the problem. No sooner in the chair as prime minister, Berlusconi made for Naples and later sent in the army to calm protests and get things moving again. By July, the PM had declared the crisis over.

Stinking garbage is not Naples’ only problem. In recent years, more blood has flown in the streets of Naples than anywhere else in Italy as a result of Mafia violence. Since 2004, around 60 to 100 people a year have died in gang warfare as rival clans of the Camorra cut each other up.

Return to beginning of chapter