Why You MUST Move—Now

© CHARLES BARSOTTI/THE NEW YORKER COLLECTION/THE CARTOON BANK. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

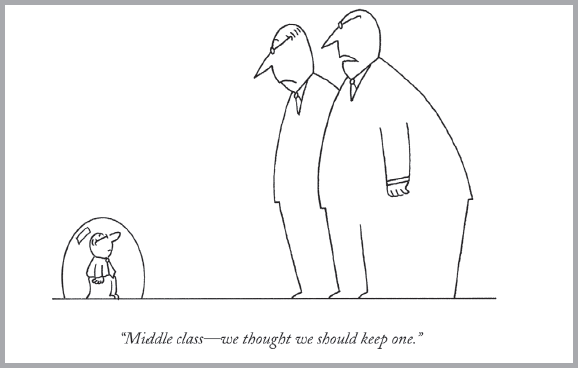

Most businesses have historically made themselves for middle-income, middle-class consumers. This began post World War II, with the great rise and expansion of the middle class in America. This was the “keeping up with the Joneses” majority, so it made perfect sense to tailor advertising, marketing, businesses, products, and services to the move-to-the-suburbs, get-a-house-with-a-white-picket-fence, a new-car-on-view-in-the-driveway crowd. And a crowd it was.

But, in more recent times, while the economic facts of American life went through great changes that hollowed out the middle class, business didn’t catch on or catch up to this, essentially continuing to gather around a watering hole that was drying up fast.

Everything about the availability of consumer spending capability was changing much faster and much more dramatically than most businesses acknowledged.

It wasn’t a difficult prophecy. In 2007, I first showed, publicly, the “new economy pyramid,” in the first edition of No B.S. Ruthless Management of People and Profits (now in the second edition). A few years before then, I began describing it to private clients and talking about it in closed-door mastermind meetings and seminars. I forecasted a literal genocide of the American middle class. And I meant: genocide, for I view a lot of it as intentional, deliberate, and orchestrated by political and certain corporate interests. But with or without that, the evolutionary disappearance of the middle class was certain. This was not difficult to foresee. The writing was on the wall, in big letters and numbers, in blood red ink. Many refused and still refuse to see it. There were denialists—in government, in media, on Wall Street. There were the ignorant, eyes wide shut. But I saw everything there was to see and made my dire prediction. Here it is, in the same visual:

This prophecy has come to pass, but it is not yet done. There is a lot more carnage to come. Temporarily, President Trump has introduced new dynamics, pulling the middle class—particularly its blue-collar members—back from the cliff’s edge. As of this writing, he has an agreement on restructuring NAFTA, pending Congress’s approval, and is otherwise dragging jobs back from Mexico and overseas, releasing manufacturing, drilling, and other industries from regulatory burdens and otherwise restarting a robust domestic industrial economy. More people now have jobs than at any other time in the past 20 years, wages are up and rising, and the middle class’ compelled savings, like 401(k) accounts, have soared. Of course, to some extent, labor shortages, open jobs, and competition for workers is inflationary, so much of the gains to those in the middle are only “on paper,” while gains toward the top are more real because of less impact by inflation. A significantly affluent person may spend only 5% to 20% of current income on necessities, so a big raise in income actually reduces the percentage spent on necessities, and the inflation becomes a voluntary tax. This ironically liberates spending more on luxury goods, services, and experiences, as we’ll discuss. The middle-income earner may spend 70% to 90% of his income on necessities or even above 100% by dependence on credit, so a modest pay raise still goes largely to necessity purchases, where the inflation offsets it very directly. In other words, everything done to rescue and preserve the middle class, while an admirable effort within the “Make America Great Again” vision, cannot alter the fact that it is an endangered species being made to die out more slowly, but dying out nonetheless.

The impact of tech, automation, and robot-ization alone guarantees a middle-class shrinkage that has to, again, pick up speed. In the Industrial Revolution, job replacement vs. job elimination was close to one-to-one. Not so with the tech revolution.

So, now, writing the third edition of this book, 12 years after the first one, I contend that moving your business’s target range up to mass-affluent and, better still, affluent clientele is all the more important and will soon, again, also be urgent.

The Two Requirements for Your Prosperity

Ultimately, to prosper you need an ample supply of customers with two attributes: ABILITY to buy and WILLINGNESS to buy. Both as a constant. Whether the economy continues to expand or reverses and shrinks, whether unemployment holds onto Trump Economy all-time lows or returns to 10- or 20-year-average norms, whether the middle class’s destruction slows to a crawl or resumes a fast pace—no matter what external conditions occur, you need a bastion of consumers with both constant, uninterruptible ability and willingness to buy. Such customers can only be found among people of affluence—not just in income, but in their net worth and emotional state. Organizing a business around any other population is, bluntly, self-sabotage. A business otherwise organized is always fragile. When heavy rains come, its crops and buildings are washed away. This book is all about building your bastion.

To move you from curiosity and half-hearted, tentative action on the advice and strategies in this book to whole-hearted, passionate, courageous, aggressive, and urgent action, I want to take a few minutes to summarize the facts of this middle-class shrinkage, provide some evidence of its impact so far, and try to paint a vivid picture in your mind of this as a present and accelerating reality.

We can begin with a few statistics. These are compiled from various authoritative sources. I have not footnoted each fact separately, but I have listed many of the sources at the end of this chapter.

How Bad Did This Get? How Bad Will It Get?

Beginning with the recession that was triggered in 2007–2008 and lasted through 2013, with the damage accelerating and peaking during the Obama years, the median U.S. household net worth plummeted by 43%. This manifested in many ways, with the upside down home mortgages being the most visible, and retirement savings accounts 401(k) the clearest loss to many. In these and many other ways, wealth—and with it the ability and willingness to buy things for years, even decades to come—erased. This damage at the top of the economic pyramid, while harsh, was and is far from devastating. If you have $10 million and lose 43% of it, you still have $5.7 million. It didn’t and doesn’t matter much to the bottom of the pyramid. If you have zero and lose 43%, you still have zero. But in the middle, it murdered and is a murderer. There it forcibly moves a middle-class consumer to a low-class consumer. There it changes a frequent discretionary spender into a buyer only of essential commodities. As it slaughtered those in the middle, it sucked the very life right out of the economy.

More important, these lost years of lost wealth and spending capability will never be recovered from by these slaughtered middle-income consumers, so in your own business lifetime you will not see a rebound of their best spending. To add insult to injury, generational replacement spending by Millennials is defying historic trends, is at a minimum, and is concentrated into few categories. Where are the first-time home buyers, home furnishings buyers, new insurance customers, etc.? Buried under a stunning $1.5 TRILLION of college debt, in their parents’ basements.

In those years, we saw a drop in net worth in almost all income categories, from the top 5% to the near bottom. Only the bottom 25th percentile saw an increase—but that is deceptive because in calculating, the government counts the earned income tax credit and food stamps as income, and Mr. Obama was the food stamp president. There are profound differences in how people in different income categories react and can react to net-worth losses. Toward the top, most high earners have options for amping up their earnings to replace net-worth losses. The high six-figure income professional can raise fees, take on more clients or patients, maybe cut overhead or staff. They have a great deal of control. My own earning capability has a dial like a thermostat on it, that I can adjust by my own hand. I always have options: writing three books in a year instead of two, accepting a few more speaking engagements I now turn down, promoting more and attracting more clients. Some top income earners have reacted that way. Others did not—but didn’t need to, and their discretionary spending capability and willingness still remained intact. They had ample money.

Toward the bottom, they traded down in price. There was a bleed from Walmart to “dollar stores” as examples under economic stress. These consumers cut where they can. They may add a low-wage job to the household. They file bankruptcy in large numbers, expunge accumulated debt, and start over with some restored spending ability. But by and large, their total spending contribution to us marketers and to the economy as a whole varies only a little, because in bad or good times, they are still spending nearly all their income on essentials, holding nothing back, neither saving or investing.

It is in the middle where stagnated and falling wages, loss of one of two jobs in the household, and cutting of hours—in part, the result of Affordable Care Act threats, uncertainties, and realities—had its most savage effects. The median income, in the 50th percentile, went from $98,872.00 in 2007 to $70,801.00 in 2009 to $56,335.00 in 2013. Take $40,000.00 out of a $90,000.00 household income and watch everything that happens. It was no surprise that home ownership dropped to a two-decade low, real estate values were slow to recover, the real estate market was poor in all but a handful of places, real estate agents’ incomes dropped, the population of active agents shrunk, and the mortgage broker and agent industry fast became a sad shadow of its former self. No surprise that roughly one-third of middle-class households fell out of that category. In short, not only did the middle-class consumer population shrink with far more falling down than climbing up, but its remaining population had shrinking buying power and had to use more and more of its buying power in fewer and fewer categories, probably excluding you and what you sell.

All of this can happen again. Never lose sight of that.

The middle class’s economic activity has always been what makes and keeps the rich folks rich and growing ever richer and what creates an uplifting opportunity for the bottom levels to move up. Small business provides most jobs and most low-skill, entry-level jobs, but most small businesses are started, grown, and owned by middle-class people, who were, for nearly ten years, severely limited in their ability to start or grow such businesses. The first year in two decades with a decline in the number of new businesses started was 2013. Middle-class consumer spending is what created and sustains suburbs, shopping malls, and the huge and wide middle of every business category: retail, restaurants, service providers. Temporarily, some of these categories can appear as healthy as ever by simply raising prices on fewer numbers of die-hard middle-class consumers. Movie industry revenues are up even as movie theater attendance has fallen and is falling. But this is the “failing condominium tower strategy”: five move out, so monthly dues are raised on the remaining 50. Five more leave, dues are raised again. Eventually, there’s one sod left with a monthly service fee of $50,000.00.

The September 17, 2014, issue of The Wall Street Journal included a report headlined: “Incomes End A 6-Year Decline, Just Barely.” Any good news was welcome. But popping champagne corks or even beer can tabs was not called for!

In 2014, the time of my writing of the prior edition of this book, there was little reason for anything but a gloomy forecast for, at best, a mud-uphill-slow recovery of the economy and a slowing of middle-class erasure.

Trump has changed all that, to an extent, in ways, and at a speed, few economists could imagine, and for which he gets far too little credit from most media and other observers and beneficiaries. I expected a significant reversal of bad fortunes and some sort of boom by Trump, but even I have been pleasantly surprised by all he has wrought. However, it is very dangerous to let this lull you into complacency. Macro forces continue their work. All things carefully considered, my forecast is for a brief Indian summer inevitably followed by a long, long, bitter cold winter for the middle class and its consumerism. If and when liberals get control of the levers of power, they will try warming up the shivering masses with socialism-lite, which will, as it always has, make things worse and lengthen the economic winter until another Trump arrives.

So, I tell you: Use this Indian summer and these good days to proactively and creatively recraft your business to move up the ladders of income, net worth, and stability of ability and willingness to buy.

There are two considerations that should govern your strategy, dictate where you sell and who you sell to. One is Comparative ABILITY to Buy. The other is Comparative WILLINGNESS to Buy. Nothing else matters more.

A Look at Comparative Ability to Buy

Consider three households—the Joneses, with low-wage jobs, combined putting just $30,000.00 a year into the coffers; the Smiths, with one at a good-paying job, the other at a low-wage job, combined $65,000.00 a year; and the Barons, who own a very profitable business from which they each draw a good salary and bonuses, and who have significant investment income, totaling $300,000.00 a year. All three households include two kids.

What is the same about all three?

The amount of money they have to spend on necessities. It goes up a little from Jones to Smith to Baron by choice. Ground beef, steak from the grocery store, premium steak ordered from and delivered by Omaha Steaks. But basically, all three families’ necessities are virtually identical. The Joneses and the Barons need the same amount of toilet paper, use the same amount of water and electricity, have to insure their cars, feed themselves and their kids, pay doctor bills and so on. Again, by choice of premium quality, or by having three cars instead of one, the amount spent may vary, but it won’t vary proportionately. The Baron household won’t spend ten times what the Jones household spends on necessities.

That means that the percentage of income spent on necessities varies a whole lot. Allow for the increase in amount spent for premium choices, more, and bigger, and say that the household’s basic and essential needs can be met for $25,000.00 a year, so that’s what the Joneses spend, the Smiths spend 50% more—$37,500.00, and the Barons splurge, spending twice that—$75,000.00. Some do, some don’t, by the way. Look at this in percentage of income terms.

The Joneses spend 85% of their income on basic and essential necessities. There are few choices in this spending. The grocery cart will feature low-cost “fill ‘em up” food. Brand loyalty is supplanted by coupons and sales. The trip to Walmart, pretty predictable. They have only 15% of income left free to spend flexibly on home improvements, on entertainment, on recreation, on elective health care, etc., and to save or invest, as long as nothing goes wrong. They have only $4,500.00 for all these choices for the entire year. $375.00 a month. One car water pump blown, one furnace repair, one kid toppled out of a tree and taken to the emergency room, and a month’s, maybe two months’ discretionary spending ability is erased. The Joneses that I’ve described are actually in better shape than most at the low-wage bottom of our economic pyramid. Most spend 100%, 110%, 120% of their income just on necessities. They are in debt, stay in debt, get deeper in debt. This is why the payday loan business exists.

The undesirability of aiming your businesses at the Joneses should be obvious. You have to win a war of base commodities, where prices are reverse elastic; constantly pulled in and pushed down. Customers buy by price, often only by price, so creating quality or service superiority has little value. A lot of money extraction has to be done in a predatory way that you may find unseemly, and that is subject to disruption by consumer protection. Again, look at the payday loan business. The “tote the note,” dealer-financed car business. The furniture and big-screen TV and appliance rental business. Selling to poor people is a grimy, grind-it-out business. You already know you don’t want to be there or you wouldn’t have bought this book. I just want to emphatically confirm your own instincts.

The Smiths spend 58% of their income on the same necessities. The Jones spend 85% of their income. The Smiths have a wider margin for error and for extra choice spending. They can be sold an expensive night out at the ballgame, a Disney® vacation, and new school clothes for both kids. With financing, they can be sold a new car or even a kitchen remodel. In dollars, they have $27,500.00 a year to use this way—nearly as much in discretionary spending ability as the Jones’ entire income. That’s $2,291.00 a month of flexible spending, saving, and investing power. A blown water pump, a broken furnace, an emergency room bill for Tommy may take a bite, but there’s quite a bit left afterward. Also, should the Smiths choose to live beyond their income—a blessed thing for us marketers—they can get a lot more credit than the Joneses, and they can service a lot more consumer debt. As of this writing, the credit card debt bubble is at its all-time high, in some ways a concealed cancer growing inside a seemingly vibrantly healthy economy. All bubbles burst. The question is when and exactly how, not if. So, this group’s ability to spend is artificially inflated and their willingness to spend subject to abrupt disruption. When I wrote this, in late 2018, interest rate increases from the Fed were happening, and more threatened, in reaction to a “too good” economy. That increases interest rates and, therefore, minimum monthly payments on all these credit cards. It also increases monthly payments on variable rate mortgages and the costs of trading in a car. Ooops. This is the danger of having your business tailored to and dependent on the Smiths. They can go sour on you with little warning. Their ability and/or willingness to buy rises and falls with winds and tides over which you and they have no control.

Now, the Barons. They only spend 25% of their income covering the same basic and essential necessities that take 58% of the Smiths’ income and 85% of the Joneses’ income. Just 25%. That means 75 cents of every dollar stays loose. No locked-in commitments. In dollars, the Barons have $225,000.00 to spend, save, or invest flexibly. If they wisely split that in half, they can plow $112,000.00 a year into tax-deferred retirement savings plans like 401(k)s, into stocks and bonds, into real estate—so that, in less than ten years, about seven years, and every seven years, they accumulate another million dollars. By comparison, the Smiths can save or invest very little. The Joneses, zero. And even if the Barons act that responsibly, they still have $112,000.00 left over to buy all sorts of unnecessary goods and services and gifts and trips. A big, fat $9,333.00 a month. Should the Barons choose to throw all sane behavior to the wind and live beyond their means—a blessed thing for us marketers—they have the ability to get a whale of a lot more credit and service it than the Smiths.

In big-thumb terms, the Joneses can handle almost no debt service, and are likely maxed out with their debt. The Smiths can handle about $200,000.00 of consumer debt, tops. But the Barons can handle $1 million of debt. Or, irresponsibly, even more.

Simply put, if your customers are low-wage or middle-wage earners, the Joneses or the Smiths, you are in very serious peril. Think of these customer populations as a place. You live or have your business in this place. Once, it was a nice neighborhood with well-kept homes, safe streets—salt of the earth type people. Gradually, it changed. Homes declined in value, got bought up by landlords—more renters, less homeowners. Soon drug dealers were on corners with unsafe streets. Such decay rarely reverses.

You have to get out.

You can.

While the middle class collapse happened (and is in recovery), the affluent population has steadied, proved resilient and reliable, and even grown. From 2011 to 2013, the number of U.S. households with incomes exceeding $100,000.00 grew by 6%. Better, the average household income among these affluents also grew by 5%. Net worth also increased by 2%, to an average $1.1 million. The Royal Bank of Canada’s big, annual Wealth Report, released in June 2014, stated that the number of high-net-worth households with multimillion-dollar net worth rose by 11% from 2011 to 2012, and rose again by another 16% from 2012 to 2013. The wealth of those households rose as well; nominally, but a 2% boost to $5 million is not chump change. Throughout the top 5% of the pyramid, there is a growing number of customers to sell to and they have growing spending capability.

More recently, even more wealth has risen to the top tiers. And since Trump’s election, truly amazing things have been occurring to the benefit of the affluent: corporate/business and personal tax reductions, record-breaking stock market gains, and with this, almost unbridled optimism.

If you are going to choose your customers—as you can and should—why not choose ones with strong ability and willingness to buy, broadly, in diversified categories, with price-elastic decision-making, and imbued with optimism or, if need arises, resilience?

Consider Comparative WILLINGNESS to Buy. Obviously, ability links to willingness. But there is a broader optimism vs. pessimism. A Gallup Poll in late 2014 showed 56% of Americans saying the economy was continuing to get worse—only 39% said it was getting better. An NBC News poll had a whopping 70% saying the economy was headed in the wrong direction. Within these numbers, there are biases by bottom, middle, or top of the pyramid.

Optimism about the economy and about one’s personal economy favors marketers. Pessimism about these things stands solidly in the way.

By late 2018, the situation reversed. Polling on consumer optimism and business leadership’s optimism were at record highs. It was hard for people not to feel this way. Unemployment hit a 50-year low, the stock market hit mind-boggling highs, and the daily economy news was virtually all positive. President Trump exuded optimism, unlike any presidents since Reagan and, before him, Kennedy.

Pessimism is a headwind against willingness to buy with all but those of significant affluence and enough age to view negative economic situations as temporary. Optimism is a tailwind that spurs a much broader demographic swath of the population’s willingness to spend. It is fine to take some advantage of times of optimism, but also smart to reinvest the extra money that flows into organizing higher income and higher net worth customers so that when the next wave of mass pessimism washes through, your business will be on higher, safer ground.

A collection of Gallup, The Wall Street Journal, and other surveys and polls that I re-examined when writing the new edition of this book revealed something most instructive about consumer attitudes from 2004, good times, to and through the crash of 2008, through the slowest recovery in history, to the present boom: the greatest fluctuations, the most erratic moves from pessimism to optimism to pessimism occurred with middle-income consumers. Low-wage earners and the working poor stayed pretty steady, from pessimistic-only to barely-better-than-pessimistic through all those years until late 2016, when they began to show a significant lift of optimism. High-income and high-net-worth people also stayed pretty steady, never dipping much below optimistic and at times more optimistic. Those in the middle were most subject to big mood swings; to excess exuberance and to fear and despair. In short, the middle-income consumers are least reliable with willingness to buy.

There is a very nice neighborhood to move your business into, where you can be welcomed by a growing number of consistently optimistic consumers with fat, open wallets. It is the affluent consumer population.

This book is the roadmap. It gives you the insight, information, inspiration, and practical how-to directions for moving from selling to Joneses or Smiths to Barons and even Big Barons. For many, this is admittedly far from a simple thing. You don’t just flip a switch. Your own thinking and attitudes and self-image may need a lot of recalibration. You’ll need vision and courage. Your positioning, your products or services, your price strategies, your marketing and selling process, and your salespeople may have to change. But I’m here to argue this is no longer a choice. The luxury of time to procrastinate about this is gone. Death is imminent for huge numbers of businesses refusing to move up the consumer income and net worth pyramid. You must now, aggressively, adapt. Or die.

The Amazon-ing of retail is but one of these compelling urgencies. It is all about converting consumers from making differential judgments by comparative expertise, experience, credibility, quality, and everything else that supports price or fee elasticity and profit to buying based on convenience, speed of delivery, and lowest price. This moves the middle-income consumers. Only particularly affluent consumers can be depended on for continuing discernment. The middle-income people will get their wills done by LegalZoom, play orthodontist at home with SmileDirectClub, and maybe even buy their car from a website and have it delivered. The affluent person will NOT have their estate plan done at LegalZoom. They will take their daughters and sons to orthodontists. They will patronize the high-end, full-service luxury auto dealership or possibly even use a broker of exotic and luxury autos. This separation of behavior is occurring at a fast pace, so you getting on the right side of it must also happen at a fast pace.

Also, inevitably, a stall, a stagnation, an episode of runaway inflation, a hefty stock market drop—as likely precipitated by meddling by the Federal Reserve as by anything else, or a variety of other kinds of economic winters will occur. People made “soft” by as big a boom as is occurring as I write this may react more badly to it than they did to 2008. Consumers greatly overextended on credit may have no choice but to stop all optional spending. This may be as much as seven to even ten years away. But it may not. It could occur gradually. It could arrive abruptly.

Your Choice

Ultimately, business owners have one of two attitudinal, behavioral, and leadership styles, choosing either complacency or urgency.

Those who tend toward complacency are often late to see, predict, and act. Of big brand-name companies ruined, at least in large part by such management, you can list Borders, Sears, JCPenney, and General Motors. The entertainment industry’s ravaging by the #MeToo movement reveals a systemic complacency about a known problem. Facebook’s explosion of crises is the result of systemic complacency and, in concert, arrogance about known problems. Huge entities sometimes take a long time to bleed out and die from their wounds often self-inflicted by complacency. Small and mid-sized companies often move from leadership complacency to crisis to extinction much faster.

Those who lean toward perpetual urgency, exhibiting a strong bias for decisive action, for proactivity rather than reaction, are often either advantageously early or at least on time. Instead of arrogance, these leaders live by healthy, motivational paranoia. They are never coasting, always innovating. My favorite big companies with CEO’s and other leadership on this list are Disney, Apple, Amazon, Cleveland Clinic, and many of my own clients, not with famous names, but with entrepreneurs making fortunes. These are companies and people who can walk and chew gum at the same time. They can execute on a current game plan, implement a future-oriented collection of next game plans, and envision and begin development of even more distant creative changes simultaneously. They act with urgency about both. Now and Next. If you examine the companies I just named, you will find a commonality of at least the past ten years and their present activities: an emphasis on being for and doing business with affluent consumers as a bigger and bigger part of their businesses.

My friend, the late, great Zig Ziglar, often told the “cooked in the squat” story: a frog thrown into a pot of boiling hot water will immediately leap right back out. But a frog placed in a pan of pleasingly cool water will stay put. He will continue to stay put as the heat is ever so slowly inched up, until the dumb frog is cooked in the squat. That’s what has happened to many small-business operators as well as big retail and restaurant chains and entire categories of businesses. The fundamental, adverse trends of middle-income consumers have worsened slowly, gradually, and these business owners have sat there, getting cooked in the squat. They are getting ever closer to a boiling point. Some even know and are splashing around trying to cool the water by blowing on it. Others are surrendering. CEOs running out the clock on their own careers, retiring, taking golden parachute treasure, and slinking away into the night.

Don’t emulate any of these dumb frogs.

Use your big, long legs.

Now.

Sources for above information include: RBC Wealth Report, Study of Income Dynamics—Sage Foundation, Gallup, NBC News, The Wall Street Journal, The New Class Conflict by Joel Kotkin, Dent Research.com, The Kiplinger Letter, The New York Times, U.S. Government research from Census and other sources, No B.S. Inner Circle publications: No B.S. Marketing Letter and No B.S. Marketing to the Affluent Letter, and www.NoBSInnerCircle.com.

Special Offer Notice: Next Steps

There is no need to wait until you complete this book to take additional, next steps forward, getting assistance from Dan Kennedy in your upward marketing to the affluent and more effective marketing overall. Page 355 presents directions to the business newsletters, online resources, and tools created by Dan Kennedy or based on his methods. You will also be invited to hands-on Implementation Boot Camps.