2.1 Introduction

Conceptions of Environmental Citizenship are core to models of sustainability. We start with an example of two very different ideologies to set the parameters of the problem. Imagine a fully libertarian society with minimal state interference where the desires and consumerist preferences of the individual trump all other considerations (Kymlicka 1990). Such a society would prioritise human rights, the free market and individualism. Nature would be a resource to be exploited to serve human needs. Hence a society with a fully libertarian political philosophy, or one which approaches extreme neoliberalism, would incorporate political and economic solutions which conserve the environment solely to meet human needs. Any threats to the environment as an economic resource might be solved through technical fixes. Rex Tillerson, the former US Secretary of State, exemplifies this approach. ‘Changes to weather patterns that move crop production areas around – we’ll adapt to that. It’s an engineering problem, and it has engineering solutions’ (Washington Post 14 December 2016).

An example at the other end of the ideological spectrum would be a communalistic and egalitarian society where the common good supersedes individual desires. Resources come to be shared on an equitable basis, and Nature and humanity co-exist in accord such that the human species have no privileged role. Human rights in such a society will be a very different construct compared with a libertarian one. In the latter, policing, if indeed it exists, will be aimed at maximising individual liberty; in a communalistic society, the role of policing is to maintain egalitarianism possibly at the expense of individual liberty. Responsibilities towards the common good in a communalistic society are prioritised over individual rights.

It should be mentioned that close to the ideology of communalism and egalitarianism is communitarianism. Contrary to liberalism, communitarianism (relating to social organisation in small communities) maintains that the attitude of uncontrolled free-market economy and consumerism towards the environment should be reconsidered. Treating the environment as an inexhaustible source of profit without thinking about the (near) future seriously endangers the planet and threatens to drive society into economic and demographic catastrophe. According to the proponents of communitarianism, for example, Etzioni (2015), measures introduced by state institutions should be combined with community efforts (i.e. efforts at the level of individuals, families and local communities). Only in this way can a reasonable and morally responsible balance be achieved between the free-market economy, the present-day exploitation of natural resources and the prospects of preserving the ecological equilibrium, giving future generations a chance to live.

These are of course extreme, and probably mythical, examples, and there are natural constraints which make their extremity impossible. For example, an extreme libertarian society would need to preserve some common resources and take into account the common good for individuals to prosper1. An extreme egalitarian society which refused to prioritise its own species would find it difficult to survive if no action was taken against parasites.

These two examples represent very different philosophical perspectives about the relationship between human beings and the Natural world. The libertarian example can be termed an example of anthropocentrism where Nature has no intrinsic value but exists to serve human needs. Anthropocentrism is often understood to reflect instrumentality, i.e. Nature as subservient to human needs. But a ‘weak’ form of anthropocentrism distinguishes between human instrumentality and human-centredness. In the latter, there is scope for respect for other species in relation to human survival, so a sense of centredness is perhaps unavoidable (Dobson 2007). Ecocentrism views Nature as having intrinsic value, life itself is the centre of ethical concern (Kopnina 2013) and living and non-living beings are seen as part of an interdependent holistic ecosystem.

An underpinning philosophical view of the environment

A particular perspective of citizenship

Key players

Our position is that these aspects are incorporated in an understanding of the political dimensions of Environmental Citizenship.

2.2 Philosophical Views of the Environment

Post-enlightenment practice has been infused with a view of the epistemological predominance of scientific rationalism and the distinction between the sentient Mind and Nature. In terms of environmental philosophy, the distinction between Mind and Nature has been prevalent both in right-wing libertarianism and in Marxism. Nor are ecocentric views necessarily configured within one particular ideology, for example, the way in which eco-fascists co-opt deep ecology ideas (http://environment-ecology.com/deep-ecology/278-ecofascism-deep-ecology-and-right-wing-co-optation.html).

Dobson (2007) distinguishes between two political ideologies connected with the environment both of which have important philosophical roots. Environmentalism constitutes ameliorative changes which can be incorporated within present values of predominantly capitalist production and consumption. It therefore comes within the compass of broadly anthropocentric perspectives. Ecologism, on the other hand, presupposes that a sustainable future means ‘radical changes in our relationship with the non-human natural world, and in our mode of social and political life’, (p. 3) i.e. one which problematises any ontological distinction between Mind and Nature.

Dobson justifies his distinction in ways which reflect the importance of philosophy to ideology and hence to political action. Consider, for example, Tillerson’s solution to climate change quoted above. In terms of ecologism, this problem of climate change lies in a distortion of the fundamental interrelations between human and biotic and non-biotic communities. It is not a matter of adjusting certain technological or social relationships but is situated in a fundamental truth: that the disjunction of human beings from the stewardship and workings of Nature is the cause of the problem. Dobson, in fact, claims that environmentalism is not an ideology while ecologism is because the latter is based on a fundamental truth about the human condition. It is, however, possible to claim that environmentalism is based on an implicit truth: the separation of Mind from Nature.

2.3 Citizenship

If ecologism entails people living sustainably, certain commitments of citizenship follow including finding a balance between maintaining individual rights and a responsibility towards the common good.

- 1.

The citizen who is personally responsible and obedient to laws and acts responsibly but does not actively question the norms of society

- 2.

The citizen who is participative but tends to act as an individual

- 3.

The socially responsible citizen motivated by a concern for social justice and who can identify obstacles which need to be overcome to attain a fairer society and cooperates with others in enacting change

Types of citizen

Type of citizen | Personally responsible (liberal/passive) | Participative | Socially responsible (republican/active) (green citizen) |

|---|---|---|---|

Characteristic | Behaves responsibly without questioning why | Behaves responsibly and takes action | Critically reflects on social justice and takes action accordingly |

Example | Recycles waste | Distributes leaflets on recycling | Discusses with others in local forums whether recycling scheme saves energy and negotiates as to how best improve recycling scheme for benefit of community |

It is the socially responsible citizen that coheres with an ecologist perspective. In characterising this form of citizenship, we use the term ‘green citizenship’.

Socially responsible citizens have an active and committed engagement to pursuing a certain way of life consistent with a more sustainable society: their duty is to live sustainably so that others may live well; they consider themselves under an obligation to act justly. In doing so, their responsibilities are global and extend beyond species and international boundaries.

A green republican perspective (Barry 2008) combines a judicious balance between rights and responsibilities, maintaining a variety of views on the public good, but also cherishes individual freedoms and common practices. It encompasses a commitment to individual agency: the choice of rationally justifiable action based on personal and social circumstances, with a critical understanding of the structural dimensions which underpin the effectiveness of sustainable action – political, economic and social dimensions.

In contrast with deep ecology (Naess 1988) or radical ecocentrism, it does not, for example, oppose consumption per se (to maintain public services such as health and education, some form of consumption is necessary) but promotes ‘mindful’ consumption, i.e. that which is consistent with the aims and philosophy of a sustainable society. Green republicanism is consistent with ecologism because it recognises the need to transform those features of capitalist society that promote hyper-consumerism and the injustice of a society in which goods are so unevenly distributed2.

Most people live within states and have contractual responsibilities towards each other codified through legal systems. Should states support voluntarism in which those citizens who choose to live sustainably take required action while others might choose unsustainable paths? Or should there be elements of coercion provided by the authority and laws of the state so that all citizens take a part in moving towards an eco-just society? Barry (2005) and Humphreys (2009) argue that green republicanism does require obligations from a state’s citizens, for example, physical labour, in helping to improve drainage systems, breeding grounds for birds, seeding wildflowers in waste grounds as well as engaging in democratic deliberation such as critical discussion of forestry developments, the role of the private sector and NGOs in environmental projects and the role of the state in international obligations such as controlling carbon emissions.

Such an approach entails fine distinctions between freedom and coercion and degrees of popular resistance to changes which are seen as leading to environmental depredation and unsustainable economic systems. So green republicanism does not mean compliance to meet what might be justifiable demands of the state, i.e. in the case of personally responsible citizens, but engaging in robust democratic deliberation, possibly backed by non-violent protest, to achieve eco-just ends.

There are interwoven issues to consider. While many scientific and technological developments are directed towards the public good in terms of their social desirability, ethical acceptability and sustainability (Owen et al. 2009), products and developments carry with them certain risks and hazards. Nanomaterials, for example, have many potential social benefits, but such small particles present unquantifiable health risks (Patenaude et al. 2015). Ravetz (2004) depicted post-normal science, as identified technologies such as nanotechnology, robotics and artificial intelligence, known by the acronym GRAIN, as those where decision stakes and social uncertainties are high, presenting potential unknown hazards.

In addition, many of the environmental challenges that beset contemporary societies often involve sophisticated levels of scientific understanding, for example, estimating the sources and levels of pollution of watercourses, the causes and extent of losses of biodiversity, the cost-benefits and quality control of organic products. Just solutions to these problems echo the democratic nature of green republicanism in ensuring that lay people and experts have open and dialogic channels of communication (Layton et al. 1993; Jasanoff 2003). Stakeholders affected by technological developments can often bring anecdotal and local knowledge which needs to be incorporated in the contexts of expert scientific knowledge, as well as open means of deliberating risk and uncertainty (Beck 1995). At the same time, forums of discussion and persuasion need to be set up for deliberations to take place between experts, lay people and policy-makers, particularly in relation to GRAIN technologies.

- 1.

Ensuring regular exchange of views between experts, policy-makers and lay people

- 2.

Obtaining public feedback to identify alternative possibilities

- 3.

Direct work with stakeholders throughout the process of deliberation to respond to public concerns in a coherent manner

- 4.

Collaborating with stakeholders and lay citizenry in the development of preferred solutions

- 5.

Empowering participants to acquire relevant knowledge in implementing decisions

- 6.

Ensuring direct decision-making is in the hands of the public (Engage 2020, www.engage2020.eu)

Criticism of democratic deliberation is that such procedures are underpinned by equal access to those democratic structures that presuppose deliberation as well as the power and know-how to activate decisions. However, this ideal does not always pertain. It can be prejudiced in the interests of those who propose the forums; it means framing the debate in a way that satisfies contending parties – not easily attained – and there is no obligation to act on decisions made (Levinson 2010). Jackson et al. (2005), however, have shown that where values, risks and benefits are discussed between experts and stakeholders at early stages of development of an innovative technology, the dialogue by all parties is deemed to be constructive.

Some other political approaches of Environmental Citizenship such as pluralism (feminist, multiculturalist) and globalism (cosmopolitan and neoliberal) are also worth mentioning. Pluralist theories (feminist and multicultural) challenge the universalism and the exclusion of difference in association with the classical political theories of citizenship (Cao 2015). Historically, certain groups of people have been excluded from full citizenship (e.g. women, sexual minorities) but also indigenous people and ethnic minorities, especially for the populations of Global South. Feminist theories challenge the public/private divide (Yuval-Davis 1997), expose the gender character of citizenship and reveal the centrality of time for the exercise of citizenship in relation to additional rights (Lister 1997) based on sexual differences (e.g. reproductive rights, right to abortion, maternity leave). Feminist Environmental Citizenship incorporates the move ‘from care to citizenship’ (MacGregor 2004), the importance of justice (especially gender justice) and social sustainability.

Multiculturalist theories advocate the recognition and granting of rights to cultural minorities, pointing out that the neutrality of the state enables the dominance of the majority, hence emphasising the need for Multicultural Citizenship (Kymlicka 1995). Multicultural Environmental Citizenship includes sensitivity to conceptions of Human-Nature relations amongst indigenous people and the incorporation of indigenous cultures, values and people (Latta and Wittman 2012).

Globalist theories include cosmopolitanism and neoliberalism. Cosmopolitans argue for global citizenship, the need for the protection of human rights and to prioritise global responsibilities (Beck 2006). Cosmopolitan citizenship poses the idea that we should all consider ourselves and operate as equal members of the political community of the cosmopolis or planet Earth. Cosmopolitan Environmental Citizenship creates a greater sense of interconnection and interdependence on a global scale beyond state boundaries (Beck 2010). Finally, neoliberalism considers citizens as consumers and advocates for the importance of corporations as agents of citizenship. It transforms citizens to Homo economicus. Neoliberal Environmental Citizenship is expressed by sustainable consumption, green consumerism and consumer-sensitive lifestyles.

2.4 Role of the State

Operationalising a green political philosophy, in this case green republicanism, entails some process of contractual obligations which enables the promotion of a sustainable society. At present, it is the state and its judicial systems which have the authority to underpin such obligations. But the role of the state in relation to green republicanism is always likely to reflect a tension between non-violent civil resistance against the state and its interests, for example, in differences over fossil fuel divestments and ensuring order and stability so such contracts can be fulfilled.

- 1.

Trust that people carry out obligations originating either from the state or through local consensus.

- 2.

Encourage local collaborative thinking to promote actions to conserve water supplies.

- 3.

Enforce stricter usage of water through punitive actions.

The first two are voluntary. The third is to ensure compliance. How far can a state committed to green republican policies steer a judicious line between voluntarism and enforcement?

In effect, the rollback of the state has meant that policies on environmental management have been carried out by the business sector or non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Chasek et al. (2018) have identified the main actors in environmental policy as states, international organisations such as United Nations-affiliated bodies and NGOs and the business sector (corporations, trade unions, scientific bodies), and policy is often a reflection of power between these sectors.

Humphreys’ (2009) depiction of an ecological state would be ‘dedicated to governance that respects ecological limits’ (p.180). Such a state would reflect intergenerational and transnational needs. This presupposes that its citizens need to recognise the limits of ecological space across space and time; hence, obligations extend beyond borders and generations. Such obligations would mean recognising disparities in ecological footprints and commitments to reduce these disparities so that resources were more evenly distributed and extended over a longer period of time. The rights and duties of states and their citizens extend beyond national borders.

- 1.

Commons that belong to all, e.g. climate systems, the Antarctic wilderness.

- 2.

Shared natural resources which extend across national boundaries, e.g. rivers.

- 3.

Transboundary externalities which exist within particular states but have international effects such as acid rain.

- 4.

Linked issues where efforts to deal with environmental concerns affect others, e.g. cutting down on air travel affects livelihood of others.

While these problems are referenced in relation to state and citizen action, some of the problems are generated by transnational corporations which can evade national jurisdictions, for example, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) agreement.

2.5 Implications for Education

So what are the implications for education in schools?

Many resources and policy papers have been written on the role of environmental education in schools. Here, however, we outline some broad principles for Environmental Citizenship and some underpinning strategies.

First, there is the need for young people to understand foundational philosophical and cultural principles that influence our judgments but which are rarely made explicit. This is a recognition of the relationship between humans and Nature. Such a relationship grows from emotional, cognitive and psychological influences including supporting young people’s respect for other living species, for example, gardening, providing a bird bath and supporting reflection on the need to protect other species but respecting Nature’s ‘wildness’. A critical education could raise questions on whether other species have rights, how such rights are recognised and the ethics of human interference in Natural processes. Central to these deliberations is pedagogy, particularly teachers’ knowledge and understanding of the topics and the need to respect and listen to young people’s ideas, what Levinson (2018) has termed knowledgeability and non-presumptiveness, in other words the practice of democracy within the classroom.

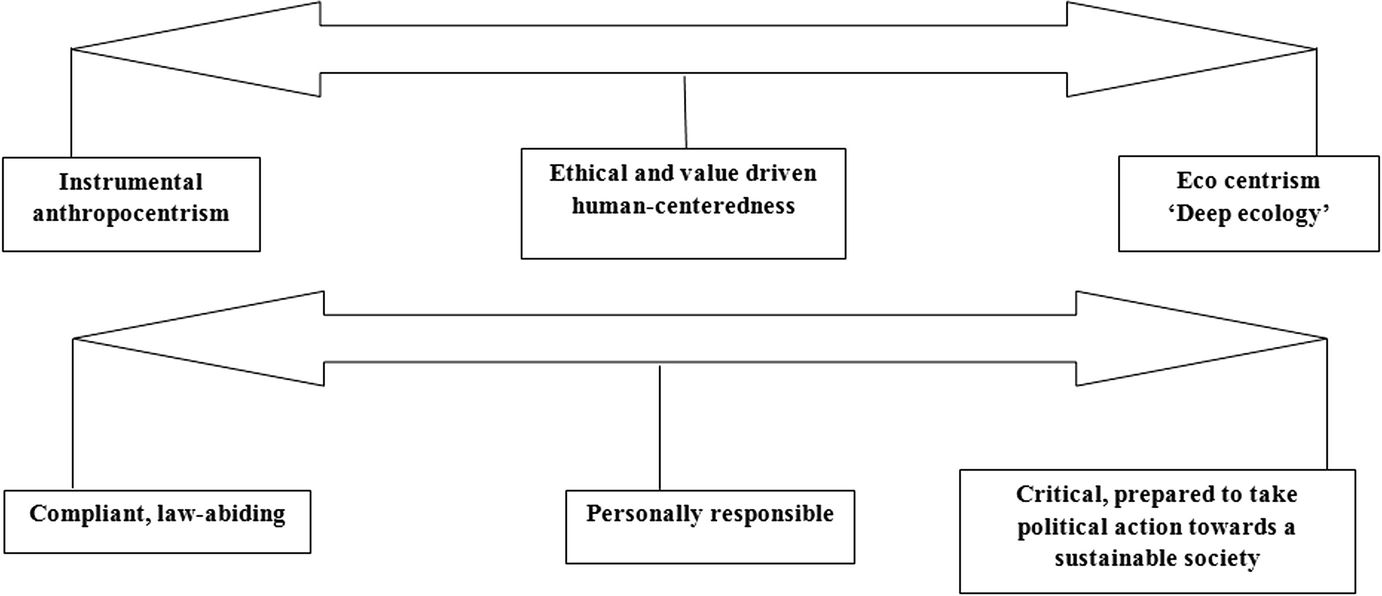

The spectrum of philosophical and citizenship relationships

2.6 Empirical Research

Expressing reflective perspectives about human beings in relation to the biotic and non-biotic spheres

Critical and informed views of Nature as a system

Understanding and expressing the perspectives of others towards natural resources across space and time – contemporaneity

Knowledge of political, social and economic structures which explain possibilities of sustainability

Understanding of values which inform a sustainable approach

Appreciating what can be achieved through political action

Willingness to specify realisable aims, to implement strategies and, if necessary, non-violent action

Dimensions of green republican citizenship

Politics (ideology) | Social (collective) | Self (subjectivity) | Praxis (engagement) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Knowledge | Knowledge and understanding of political systems and power structures (understands where authority lies, e.g. knows who to lobby to promote open spaces for local species) | Knowledge of interconnections between culture and power for transformative action (can identify diverse political and cultural discourses, e.g. knowing how to negotiate with authority) | Sense of identity (understand how they are positioned in relation to a particular issue; can identify connections as an individual to broader social and global issues, e.g. effect of own and social actions on global climate change) | Knowledge of how to affect change for eco-justice (knows how to garner support to effect change, e.g. through local action groups) |

Skills | Critical political analysis (understands importance of status of knowledge) | Capacity to engage in dialogue and deliberation (takes part constructively in classroom discussions but also understands limits of deliberation) | Reflect on own status in society (can put themselves in others’ shoes) | Imagines and articulates position of a more socially and eco-just world |

Values | Commitment to values underpinning sustainable living | Ability to reflect others’ values and positions | Consideration of self-worth (able to express their particular perspective) | Informed, responsible, reflective ethical action |

Dispositions | Actively questioning environmental injustice (e.g. slave labour production of coltan for digital technologies resulting in displacing people to rainforests) (Lalji 2007). | Responsible towards self and others (awareness of own ecological footprints in relation to others) | Autonomous and self-critical (can listen to others’ perspectives respectfully while maintaining different political commitments) | Commitment and motivation to transform society responsibly (communicates reasons for actions to others) |

Table 2.2 could be a starting point for identifying the constructs of an education for green republicanism.

This chapter is based on work from Cost Action ENEC – European Network for Environmental Citizenship (CA16229) – supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.